In the samba city, touristic point where people from all types of places come to lose their belongings, have a beer at the Lapa, see the beaches and the football, we seldom take a moment to reflect if there was ever peace in this land. A renowned Brazilian film, though controversial, makes an attempt at portraying organized crime and the public security in Rio de Janeiro: of course we are talking about Elite Squad.

The first of two films shows the police brutality, the corruption among the lower ranks militaries and the impunity granted to drug trafficking. The film got many negative reviews for supposedly glorifying the “honest” yet sociopath officer despite all the corrupt and complacent ones. As a reckoning, Elite Squad 2 portrayed the structural logic of public security that makes fighting crime a low priority while opening doors for law enforcement officers to act as militias exploiting the “free of crime” communities.

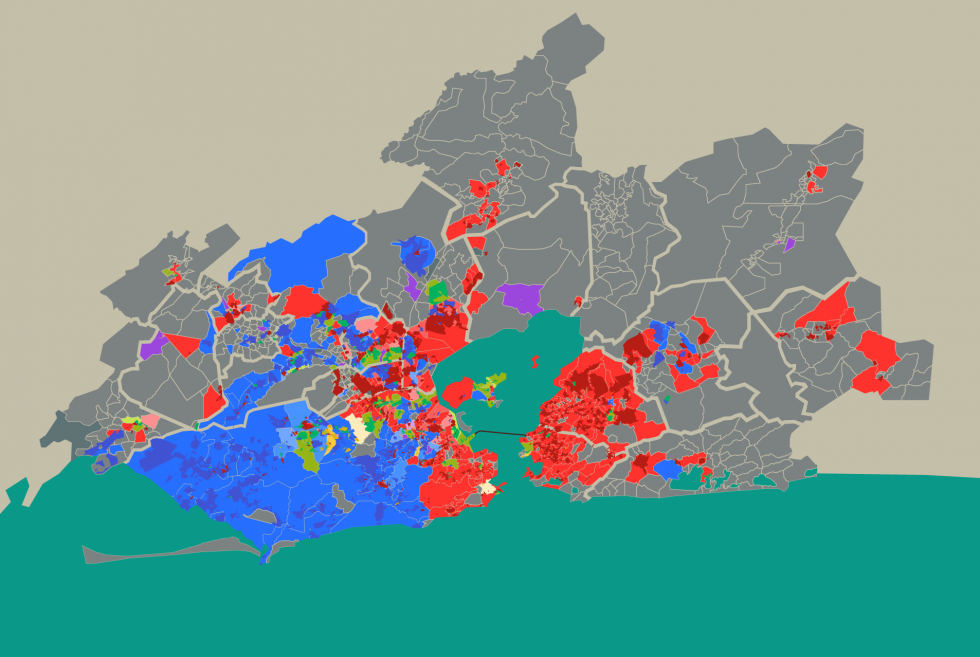

Gas, light, internet, loan sharking, rents, everything would go through the militias. They were backed by politicians that described them as “polícia mineira” (a slang that even the city mayor has used to refer to the parallel police that do the dirty work) as a solution for the security of the communities and as counterpoint to drug trafficking. The reality, however, is that in many places the militia supplements its profits by “outsourcing” drug trafficking, allowing allied groups (Amigos dos Amigos e Terceiro Comando Puro) to sell drugs in exchange for a percentage of the revenue.

The militias appear in the beginning of the 2000’s, while the Comando Vermelho dates from the military dictatorship (1964-1985), when common and political prisoners organized in Rio de Janeiro to form the now second biggest Brazilian criminal faction, losing only to the São Paulo’s PCC. Nevertheless, activists and researchers show that selective police operations open space for paramilitary forces to fill the vacuum of criminal organizations in such a way that the militias are connected to the state machine itself.

In the press it is speculated that one infiltrator hired by the Brazão brothers overestimated Marielle’s political potential, so she became the preferential target of the attack. The simplest reason to understand this is the disproportionate difference in relevance between the councillor and her political godfather, Marcelo Freixo. Ever since he led the Parliamentary Commission, he has not stopped having personal security, as he is still the target of threats. Besides that, it was Marielle who personally investigated the Federal Intervention at Rio de Janeiro in 2018. Rivaldo Barbosa would have demanded, according to Lessa’s denunciations, that Marielle’s murder should not take place in the vicinity of the Council Chamber, for otherwise it would have been impossible to cover up the case. It would come as no surprise to find out that the transversal interests of the militias and public power had converged in a young politician to communicate their bloody message.

The reason for the killing seems to clarify now, or better put, to open space for new questions and a militant reflection. What would have been the fuse for the killing?

Inside the institutional and identitarian left, it was common to say that the Blackness of the councillor was an essential mark to determine the choice of her killing. Despite having an underlying truth to it, and the fact that Marielle indeed had ascended politically because of her militancy with mostly Black poor people, Lessa’s denunciation points directly to her influence over a matter of territorial dispute. Whether or not we agree with this underlying truth, it seems that Marielle’s assassination had less to do with the individual, and more with the ideology she defended – and the people with which she was dealing.

The militia hypothesis

In order to finance its activities and attract those officers who believe, with the best of intentions, that they are improving the city, killing the ones who are in the way, it is crucial that the militia agents don’t rely solely on the negligence of public power and punctual agreements with the community leaderships – they need to develop their own means of funding. Usually it is through the re-sale of gas canisters, water supplies, and internet and cable tv, besides rents. The militia establish its prices and hold the monopoly over their provision, so that no doubt is left about the success of their enterprise. It is true that favelas are not just residential areas; there are also many small businesses in the region, but this is only possible if the militia considers that the fees it can charge from such businesses surpass the profit of running the business itself.

Therefore, the militias have the same exact mechanism of social control from the criminal factions, which exert totalitarian control over the right to come and go and freedom of speech, besides constant exploitation. For the social movements that survived the dictatorship on a national scale, the paramilitary groups hold a cruel resemblance of militant impotence.

The discussion about the regulation of the urban areas in Jacarepaguá that involved both Marielle and the Brazão Brothers seems to relate directly to the expansion of the parastatal control in the West Zone where it’s particularly difficult for militants to intervene politically. In the first place, this expansion makes urban occupations (squats) impracticable. The militia already uses many strategies of extortion against public housing complexes. In businesses where the boss is together with the militia, it is impossible to recur to the labour justice for any matter of working conditions, or even to pressure to improve them, as the workers are subjected to the risk of a “visit” from the crime’s executioners. An interesting example was shown in an article that reports the pressure of militias and drug dealers upon delivery workers not to strike in São Paulo and Rio.

In 2023 it was ordered to set 35 buses on fire in the municipality of Rio de Janeiro as retaliation for the death of the son of “Zinho” – leadership known by the police and involved in diverse assassinations. This serves as proof that the militias threaten the stability of urban flow itself, blocking the struggle for ending public transportation fees.

In the few last years the militia hypothesis has not seemed exaggerated. A revealing coincidence is the apparent connection between the family of the former President Jair Bolsonaro and the militia, though this was never clarified. Ronni Lessa was a neighbor of the Bolsonaros and, according to the former president, the daughter of the militia member used to date his youngest son, Renan Bolsonaro. Adriano da Nóbrega was visited by Jair and Flávio Bolsonaro (the son of Jair, also in politics) at least two times when he was incarcerated. Bolsonaro supposedly met Lessa in the day before the murder of Marielle. Élcio de Queiroz, who is also involved in the killing of the councilwoman, has pictures with Jair supporting his first presidential campaign in 2018 (he would later be elected). 117 rifles were confiscated with a friend of Lessa in a mansion in the Barra da Tijuca neighborhood, where the Bolsonaro family lives.

As of today, Bolsonaro is ineligible. However, he still holds significant political capital and direct or indirect influence over the elections in every state of Brazil. If the command of the Federal Police had not been changed, and the government had not been once again taken by the democratic center-left, maybe we would not have the information we now have about the assassination of Marielle Franco in 2018. Maybe we wouldn’t even remember the relevance of names like Brazão and Rivaldo. The “urban militianism” (term used by researchers on the militias in Rio) unfortunately does not give signs of being in its last days, despite the growing expansion of the Comando Vermelho, partly explained by the intense change in commands in the last two years.

The social struggles also haven’t ended, and in face of the apparent weakening of the militias and in face of the less “Bolsonarists” institutions, it is possible that the next two years will be of a new upheaval of urban struggles and social victories. As long as the left comprehends the obstacles it has ahead and reflects about the field of action.