In the first round of the French legislative elections, held on June 30, around 33 million people voted while 16 million stayed home. Ten and a half million (33.2% of those voting) chose the far-right Rassemblement National (RN) and its close allies.

On the other hand, nine million (28.1%) supported the left alliance, New Popular Front, in which the radical left party France Insoumise (FI) is the most influential component.

President Emmanuel Macron’s candidates received 6.8 million votes (21.3%) and 2.1 million (6.6%) voted for the traditional conservative Republicans.

There is plenty of defeatism around. At the same time, there has been more dynamic antifascist activity in the past three weeks than in the previous three years, and this is the most energetic left election campaign for several decades.

Key questions

The most important question is not how many disagreements anticapitalists have with this or that political force. Rather, we have to start with class interests and ask what is useful for working people.

Indubitably, the New Popular Front between FI, the Socialist Party, Communist Party and the Greens is useful to the working class, and it was very much pressure from below which made it happen. Because of the two-round voting system, the mere existence of the Front took a few dozen seats away from the fascists. In addition, its program has mobilised tens of thousands of activists for a real left alternative.

The program, presented as 150 or so priority policies, includes pledges to raise the minimum wage by 14%, end homelessness, dismantle the most violent cop units, declare immediate recognition of the state of Palestine and end arms sales to Israel.

Compromises were made: leaving NATO is not mentioned and the question of nuclear power is absent. This does not means that the Greens or the FI have abandoned their policies on these questions. Each signing party may continue to defend its own priorities.

The parties agreed to share out the constituencies and not stand against each other. This means that some of the candidates have nothing in common with anticapitalists. For example, the Socialist Party chose social liberal and former President François Hollande as a candidate. This was the price of an indispensable alliance.

At present, the fascists are far more powerful inside parliament than they are outside. Despite receiving up to 13 million votes in some elections, the RN cannot organise mass street demonstrations. In most towns they have little party structure. Winning more than 200 seats in parliament, which looks possible, could be a huge step forward for the RN. Therefore, this week the electoral battleground is the key one.

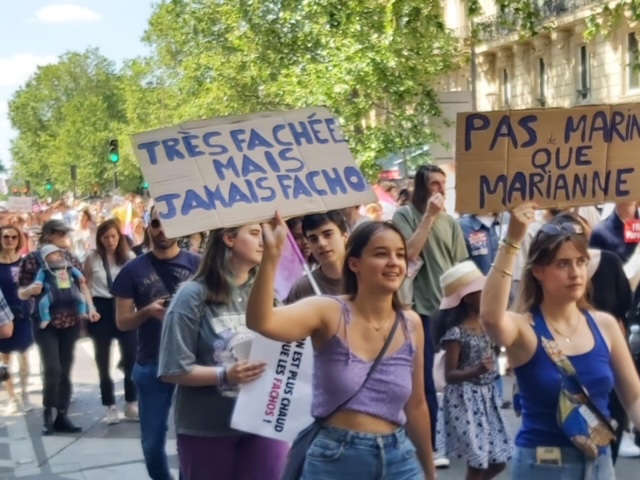

Those on the left who counterpose the left electoral alliance with the struggle on the street are mistaken. The Front has encouraged antifascist activity. Young people on demonstrations are chanting “Siamo tutti antifacisti!” (“We are all anti-fascists!”) and “Front populaire” (“Popular Front”), as well as “Free, Free Palestine!”

Also tremendously useful for working people is the broad antifascist activity that has been storming France this fortnight. Left parties, trade unions, women’s rights groups, charities and pressure groups such as ATTAC and Greenpeace are pulling out all stops, leafleting railway stations and contacting all their supporters.

800,000 people demonstrated in more than 200 towns in a trade union initiative. Women’s rights groups organised marches in dozens of towns. Every day there are rallies called by youth organisations or the radical press, and so on.

A huge outdoor concert on July 3 in Paris heard from Nobel Prize-winning novelist Annie Ernaux and dozens of speakers. Appeals against the far right are surging from unexpected circles. 800 classical musicians signed one appeal, 2500 scientists another, and there have been similar initiatives from social science journals, university chancellors, rappers and rock musicians. Star footballers, cyclists from the Tour de France and many more have added their voices. Academic societies, the left press and the Theatre festival in Avignon have organised appeals or events.

Although trade union representatives often concentrate on the horrific economic policies of the far right, others on the left have rightly prioritised antiracism. At his mass meeting in Montpellier ten days ago, FI leader Jean-Luc Mélenchon put antiracism, and specifically the fight against Islamophobia, front and centre. On prime-time television, FI MP Clémence Guette and others emphasised that racism is at the centre of RN’s ideology.

Mass involvement in antifascist activity of all kinds is one way of countering the 24-hour-a-day barrage of media propaganda about “left and right extremism” and lies about the supposed violence and antisemitism of the radical left.

Inseparable

The electoral campaign of the left, and antifascist activity, are not generally separate. In one week, more than 50,000 people registered as supporters of the FI, and tens of thousands asked to get involved in the campaign. Dozens of buses are criss-crossing the country, bringing FI members and other activists to help out in towns where the RN is strong. Mass door to door canvassing — not a traditional part of election campaigns here — is becoming commonplace.

More antifascist activity, the establishment of permanent networks for antifascist education and combatting harassment, and a stronger FI are all necessary.

Despite the limits of the FI’s “citizens’ revolution perspective”, the party has loudly denounced the genocide in Gaza and brought the fight against Islamophobia into mainstream left politics — from where it had been shamefully absent for decades. It has also succeeded in putting the importance of taxing the rich, moving to 100% organic farming and 100% renewable energy centre stage in the political debate.

If the FI and, in particular, Mélenchon are attacked so viciously, it is because they represent a radical break with neoliberal business-as-usual. This is the reason for their very high scores in multi-ethnic working-class parts of town, and their ability to attract large numbers of new activists.

The second round

In places where no candidate received over 50% of the vote, a second round of voting will take place between the top candidates. Candidates need at least 12.5% to reach the second round, meaning in some places there are still more than two candidates running.

Macron, having spent years encouraging far-right ideas, is now declaring: “Not one vote should go to the National Rally.” However, some of his MPs refuse to call for a left vote in towns where only the left and the fascists are in the second round contest.

On the left, the question of what to do when a left candidate came third in a town in the first round is causing heated argument. Supporting Macron against RN’s Marine Le Pen has been disastrous over the past seven years. On the other hand, it is possible to withdraw a left candidate without calling for support for the right-wing or centre-right candidate remaining in the race. FI has generally limited itself to campaigning for “not a single vote for the RN!”

The results of the second round of the elections on July 7 are impossible to predict. What those who abstained last week can be persuaded to do is crucial.

The most likely outcome is that there will be no overall majority, but no coalition will be easily constructed. Much of the right will refuse to govern with the RN.

A “government of national unity” including conservative Republicans, Macronists and some Socialists and Greens is being spoken of. This would be disastrous. A national unity government that abandons pro-working class radical reforms is likely to prepare the way for a stronger RN government in a few years.

A small section of the right wing of the FI might even be tempted by this. However, there may well not be enough MPs on the left to make such a government happen. In any case, like every political configuration in this deep crisis, the New Popular Front is fragile.

If no stable government can be formed, extra-parliamentary struggle will be more important than ever. The building of a strong radical left must continue, and Marxists must work inside it while keeping their own fraternal but fiercely independent voice.