Hi there. Thanks for agreeing to talk to us. Could you start by briefly introducing yourselves?

MC: My name is Mark Curran, and I’m an activist, artist and educator. I’ve lived in Berlin for almost 21 years and also work in Ireland.

CG: I’m Clare Gallagher. I am a senior lecturer in Northern Ireland and I’m also an artist.

Could you say something about the exhibition in which you were supposed to exhibit?

MC: It is called Changing States and officially the largest group exhibition of contemporary photographic art from Ireland ever exhibited. It’s part of a year long Government of Ireland cultural program in Germany called Zeitgeist24. It was curated by the Photo Museum Ireland, IKS Düsseldorf and the Haus am Kleistpark in Berlin.

It is looking at ideas of identity, post-colonial history – how things have shifted economically, socially, and politically on the island of Ireland. It is a significant show of contemporary work.

CG: There were three themes – political landscapes, notions of home, and changing identities. It’s very hard to ignore Palestine, when themes like these were directly identified by the exhibition.

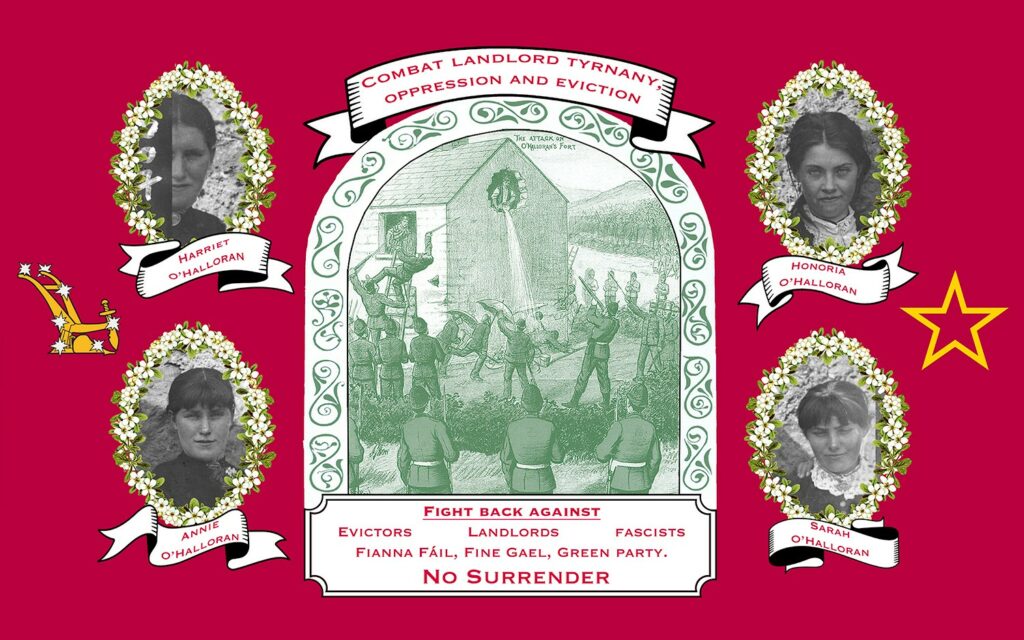

MC: When you grow up in Ireland, you’re aware of the anti-colonial, anti-imperialist struggle in Ireland, you’re aware of the struggles in South Africa and Palestine. 100 years ago, Britain said that Palestine was to be ‘a second Ireland’. The long legacy of the identification between the struggles has been implicit, if not explicit.

I’ve been involved around the issue of justice and liberation in Palestine for decades. And in Germany, you’re aware of the belligerent repression, criminalization, the sort of brutal violence used against anybody who shows support for Palestine. But since October there’s been a shift. It’s just come down like a hammer.

Witnessing that violence weekly, including again this past weekend, where we saw Palestinians, Jewish brothers and sisters getting arrested, as well as children and other activists who were peacefully demonstrating. It was clear for months that unless there was a ceasefire, there was no way we could contribute to an exhibition. It is important to note that Kate Nolan, one of the other artists involved and myself, had ongoing communication with Photo Museum Ireland for several months regarding the ongoing repressive situation.

Germany has a central role and complicity in the genocide in Gaza and the violence in the occupied West Bank. It’s the second largest supplier of weapons. The arguments about German Staatsräson made it clear that this was going to make it problematic. There are claims of freedom of speech without restriction. This is definitely not the case in Germany and does not apply equally.

CG: I’m from the North of Ireland, and I grew up during the Troubles with the really difficult legacy of colonialism. We felt very isolated in the North. We recognize some of those same struggles in other places around the world, like South Africa, or Palestine.

Through Palestine we see ourselves as part of something bigger than us and not just this problematic corner on the edge of Europe. So Palestine means a lot to us.

What you’re doing is part of the ‘Strike Germany’ initiative. Could you say a couple of things about Strike Germany?

MC: This is a call by cultural producers who have witnessed both the brutalizing of activists and the cancelling, silencing and repression of other cultural producers in Germany. In some cases, people are being cancelled just for calling a ceasefire, to stop killing children. Palestinian and Jewish brothers and sisters who have spoken out have and are being cancelled.

The call is an act of solidarity, to acknowledge this situation. Who gets to speak? Who gets to show? Who gets to express a position? And who doesn’t. This is deeply problematic, undemocratic, it’s repressive, and it’s racist.

CG: The first three of us who withdrew from the exhibition are academics. When we teach we’re talking about how to work ethically, and setting an example for people who have a bit less privilege because they’re earlier in their careers. It’s really important that we lead with this. There’s layers of significance in how we conduct ourselves.

There has been a huge devastation of education in Gaza. It shows in so many ways how we’re all connected, and that we can’t isolate ourselves and silence what we do for expediency or our careers. It’s so incredibly important to do this.

I’ve spoken about Strike Germany with some friends who are artists. They support the campaign and say that it’s great that international artists are boycotting Germany. At the same time, they live in Germany, they work here and exhibit here. Germany is their livelihood. What can German-based artists do without putting themselves out of business?

MC: I can appreciate and understand this but perhaps, there’s a need now to take a position. As Clare said, there’s also a need to acknowledge the younger and emerging artists who joined the boycott. For them there’s more of a potential cost. That’s incredibly brave. I won’t speak for them but imagine they have had to consider how it may affect relationships or possible future opportunities.

There’s also a moral imperative in terms of what we’re witnessing. There are 20,000 artists in Berlin, but when I go to the demonstrations every week, while some definitely are present, I wonder where most of those artists are. Where are the people who describe themselves as activists and radicals who are bound up in the struggle for Palestine?

People say “Oh, I wouldn’t have stood by in the 1930s. I would have stood up”. Well now, this is the moment. I’m constantly amazed and in some ways really disappointed when so many with privilege and legal status remain silent. At every protest, I see people that I know – who maybe don’t have full status in Germany, but show up every week while others with German and EU passports are nowhere to be seen.

We’re witnessing a genocide. So it’s hard not to judge them, but it’s really important to say that it’s never too late. Come to the protest next week. Show up. Use your privilege to use your body as a means to support, walk with and protect someone, who may have less legal privilege. Show solidarity.

CG: I would just add that we can feel quite isolated when we think about taking action. But when we start to make these actions of solidarity, it’s incredibly supportive. We feel that we’re part of something.

When each of us made a statement that we were withdrawing from the exhibition, we got a huge amount of messages of support. People recognised what we were doing. It’s really daunting to do, but it’s much, much better to be in that expression of solidarity.

MC: We discovered too that the institutions, who organised the exhibition reprinted the complete catalogue a week before the show opened. All the artists who withdrew from the show were removed, and there is no reference to the withdrawal.

This was the same week that the Republic of Ireland recognized the State of Palestine. It’s not obviously the same level, but the institutions in some ways are mimicking the strategy of silencing, of erasure by the German state. There has been little or no dialogue in a meaningful way. That saddens me.

CG: There was originally going to be a statement on the wall and in the catalogue addressing the fact that a number of artists had withdrawn. Then some backtracking happened. This was really sad for an exhibition which is about contested territories, the politics of home and place and Ireland being connected to places further afield from our isolated island.

It is really sad to have been so comprehensively removed from it, rather than to acknowledge that as artists, we’re part of that community, not that our voices shouldn’t be heard.

How would you react to the argument that if anyone needs art, and particularly political art, at the moment, it’s people in Germany, and that by striking you’re just giving over the artistic sphere to the right wing?

CG: I understand that argument. But that’s just feeding a status quo, which is very comfortable. And often we have to make things uncomfortable for there to be change. When we go on strike, we stand on picket lines and have difficult conversations with students about why we’re outside the university, and not inside the university teaching.

But it’s only through doing these difficult, uncomfortable things that we drive enough attention to the situation or provoke conversation about it, because otherwise it just ticks along.

MC: I hate to say this but it’s a white, liberal middle class response to ask why you can’t engage and that it’s more complex. But I think we’ve reached beyond that point. It’s about positioning, about making a statement. It’s a small statement to make, but critically, it is an act of solidarity.

How have other artists responded to you withdrawing from the exhibition?

MC: Most have been incredibly supportive and understanding the rationale. Some less so. There is resonance with what happened at the time of the struggle against Apartheid in South Africa. Can you change things from within by maintaining your presence? This was shown to be a completely failed strategy. There comes a point where you have to make that decision and take a position.

Are there plans for similar actions like withdrawal for exhibitions?

CG: I don’t know about Germany, but in Ireland and Britain there are campaigns around sponsorship for writing and music festivals which are sponsored by Barclays and others with links to the genocide. Their sponsorship of Latitude prompted a lot of musicians to leave. The Hay literary festival has changed their sponsorship because so many writers dropped out. People in the Arts are good at taking a stand, even at cost to themselves.

MC: Musicians are pulling out of particular festivals, like recently in Hamburg. I’ve also been trying to contact some writers who weren’t aware of Strike Germany. You can actively go out and try raise awareness of the campaign, including like with this interview, and also about the weekly violence we witness on the streets of Berlin. Just this weekend, I had an English friend who was aware of the situation through material I had shown him, but when he was in Schönhauser Allee, he was shocked at the level of police violence, provocation and intimidation that we witnessed.

We were walking beside this Jewish man, who was the first person we saw arrested by the police. For my friend, the world was turned upside down. In Germany they don’t seem to see the difference between Zionism and Judaism. Well, maybe they do, but it’s just constant that you’re walking with Jewish friends and they and you are being accused of being antisemitic.

Do you think there’s a specific way in which you can react artistically to Palestine? You’ve talked about going to demonstrations and withdrawing, which is important but feels a little negative. Is there a positive way in which artists can respond to what’s happening in Palestine?

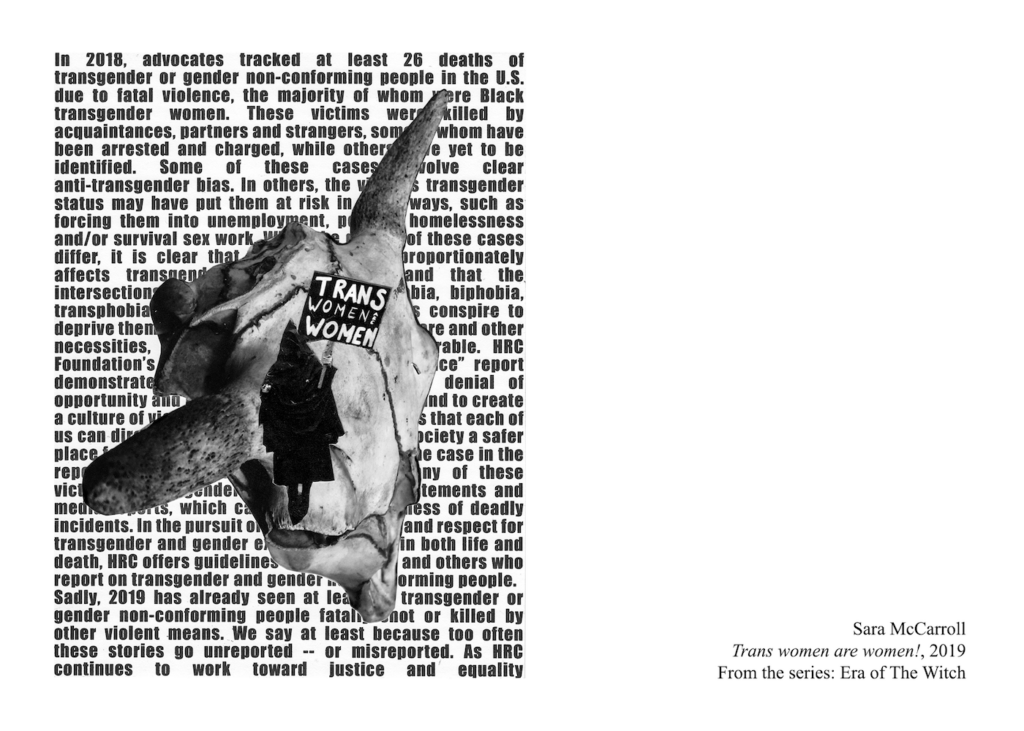

CG: There’s artists’ groups like Artists Against Genocide which are really, really active. People are learning Palestinian embroidery, sharing skills. It’s all a way of constructing something in that absence in our own ad hoc way. This is immediate and often as artists we may work much more slowly, and with more reflection. This is a way of working which isn’t probably our typical way, but it is what we’re doing.

MC: The Irish Bloc Berlin, who I am involved with, are organising a Solidarity Céilí this weekend to fundraise for Gaza, where there will also be Palestinian artists. We use whatever little platform we may have to raise awareness, be there, and show support.

If I’m honest, I have lost friends, colleagues, artists who have unfollowed me on social media, as have museum directors, photo editors, gallerists etc., but I’ve made a whole new network of artists, activists and friends. It brings great clarity, which is equally important in terms of positioning. And that is also why, while it may seem negative, withdrawing from the show has also been empowering.

Hopefully, there’s going to be artists who will read this interview. Certainly, there’ll be people who consume Art. What can they do to support you or to join with you in increasing the artistic response?

MC: People have to make themselves aware, to educate themselves, you know, go read a book. We can give recommendations.

In terms of artists, they need to show up. We’re at a position where, as people say, Palestine is going to save us all. Clare mentioned already that it’s all connected. Step up, be present, be supportive, show solidarity. Showing up is an extension of one’s being, one’s ethic, one’s moral compass.

It’s also about the world, because we can’t normalise this. We must see what is legally happening both internationally and in Germany every day. Lawyers here have told me that the authorities are literally interpreting the law, sometimes daily and definitely in terms of protest. They’re the harbingers of the future. This is something you might think is way over there, but this is all about all of us, about here and now and recognising that is critical.