It’s been a momentous three months since I last examined major issues related to housing in Berlin and developments in my Reichenberger Straße neighborhood. In this interval, the most noise was generated by the German Constitutional Court ruling that the rent cap law (Mietendeckel) – in vigor for a scant five months – was “null and void.” That setback for tenants stimulated more support for the “Deutsche Wohnen & Co. enteignen” (DWE) campaign to socialize the largest profit-oriented housing companies. In my kiez, other events reflect a social rights crisis.

Mietendeckel

First, the Mietendeckel. Beginning on 23 November 2020, Berlin landlords had to unilaterally reduce all rents exceeding the legally permissible square-meter price (not counting heating costs). Despite warnings of the need to put aside the amount “saved” as a result of the rent cap, many tenants are now having difficulties paying the arrears. Not only did the COVID-19 pandemic erode or annihilate livelihoods, but also some 60,000 new leases were signed while the rent cap was in effect. Landlords were betting (and doing everything they could to ensure) that Berlin’s pioneering new law would be overturned. They provisionally charged new tenants legal rents but forced them to sign leases stipulating considerably higher “shadow rents” (Schattenmiete) should the rent cap be overturned.

In the wake of the decision, the six municipal housing companies, along with the private Vonovia and Heimstaden companies, announced they would waive repayment. (Each tenant must get that in writing.) Financial help for paying arrears is available in the form of grants (repayable without interest) and subsidies. The Berliner Mieterverein (BMV) has an FAQ in English regarding the decision. Since the issue is very complicated and the legal basis is not always clear, any demands to pay arrears or a higher rent should be checked.

On 14 April, an announcement was made that the long-awaited decision about the Mietendeckel would be made public the following day. That night, many Berliners slept fitfully. Given the mighty real estate lobby and the political parties that challenged the law, perhaps the decision was foreseeable. Nonetheless, the outrage and distress it caused was so great that by 6 pm on 15 April, 14,000 people had gathered at Hermannplatz to protest. I wore my purple and yellow DWE vest, with petition lists in my hand instead of a camera, although I knew there’d likely be great photos to take. Sure enough: The façade of an apartment building overlooking the demonstration was a perfect illustration of the moment. From the top floor, a bespectacled old man scrutinized the crowd. Two floors beneath, a henna-haired middle-aged woman leaned far out her window, enthusiastically banging a pot – and between them a head-scarved woman around 40 stood still a long time behind her closed window before pulling the curtains shut and disappearing. On the building’s first floor, as if frozen, a young girl stared blankly at the crowd. That evening, many people approached me, eager to support the DWE referendum: Now more than ever!

Political reactions to the over-turned rent cap also followed immediately, with parties acknowledging that high rents are a problem. Because the decision solely focused on Berlin’s lack of jurisdiction to pass such a law – rather than its content – the main positive outcome of the debacle is the new, broader demand for a national rent cap, along with more support for DWE.

Deutsche Wohnen & Co. enteignen and housing cooperatives

However, true to form, conservative politician Mario Czaja began a misinformation campaign in Marzahn-Hellersdorf, “explaining” that DWE also plans to socialize the housing cooperatives (Genossenschaften), which with around 200,000 Berlin apartments represent 12 per cent of the city’s total housing stock. Individual cooperatives are also misrepresenting the DWE campaign and could cause considerable damage. This despite DWE’s statement: “We are specifically only concerned with ‘profit-oriented companies’ [and] want to expand the public sector, which also includes cooperatives… [which] should be preserved along with other forms of collective residential property.” Although DWE took legal action to force Czaja to cease and desist, that won’t end the debate – especially if the referendum passes on 26 September. On the DWE blog, someone posted that many of the cooperatives behave as if they’re part of the private market although their raison d’être is to serve the common good, while many, especially older, coop members are discovering that their housing costs have risen significantly.

Meanwhile, reading the October 2020 issue of the Berliner Mieter Gemeinschaft e.V.’s Mieter Echo magazine has provided me insight into the six municipal housing companies, which sociologist Andrej Holm describes as following “business logic,” noting that they’ve fallen far short of their goal of building 6,000 new apartments annually. Marcel Schneider observes that between 2001 and 2018, “social” rents in Berlin rose faster than incomes and concludes that social housing tenants are financing the acquisition policy of the former GSW (social housing company) apartments that the city sold for a ridiculously low price to “locust” investors in 2004. Joachim Maiworm analyzes their supervisory boards: As stock companies (Aktiengesellschaft, AG) or limited liability companies (GmbH), public housing companies must operate profitably (wirtschaftlich). Although the city is supposed to ensure that the companies fulfill their public service obligations, “the selection of supervisory board members shows that there is a lack of political will to manage public companies for the common good…. Despite their social welfare mission, the public sector ultimately acts like a private company.” Maiworm concludes that a new public structure is needed to ensure that.

Also in that issue, Rainer Balcerowiak enumerates public housing company subsidiaries whose activities are beyond any government influence. These companies work with private corporations, including Deutsche Wohnen, managing private investments, negotiating loans and engaging in other activities that cannot be described as “serving the common good.” Balcerowiak also finds that for that, “Sustainably changing the structures of the municipal housing market requires bundling both the existing housing stock and new construction activities under direct municipal responsibility, in a state-owned enterprise or an AöR (public-law institution).” This represents a major challenge to Berlin housing that is not yet getting attention. That inevitability, however, could be another reason why the real estate lobby and conservatives and neoliberals are so upset.

The temperature of the discussion about Berlin rents did not drop when, on 10 May, the DWE campaign published its proposal for a law regulating the socialization process. The referendum is about requiring the city to pass a law socializing the major profit-oriented housing companies that each own more than 3,000 units; it does not propose a specific law. However, DWE’s bill shows that socialization is affordable by means of “compensation bonds” to be repaid through rental income (minus maintenance costs) over 40 years. That sounds unlikely to ever garner the votes needed… until you read that such bonds can be transferred and traded on the market, which means bondholders can sell them and receive full compensation much sooner. Socialization can be accomplished without expensive loans or city funds. Compensation is based on the “fair-rent model… based on the maximum affordable rents for households at risk of poverty…. The affordable net rent per square meter […] varies according to amenities and residential area.”

The bill guarantees “public service use” as stipulated by Article 15 of Germany’s Basic Law and permits the owners to receive the highest compensation allowed for that. According to Sebastian Schneider, who was in charge of developing the proposed law, “This […] makes socialization and new construction possible.” DWE maintains that in the wake of the overturned rent cap, socialization is the only way to stop the rapid and inexorable rise of rents. Of course, the proposed law is very detailed, covering concerns such as the risk of companies evading socialization through complicated and opaque business structures and the re-privatization of properties – and remains open to debate and improvement.

We are entering the last month of signature collecting. This huge effort on the part of more than 1,700 volunteers and the core group who have been working on this issue for years must not have been in vain!

As I write, I’m feeling very anxious. It will soon be clear whether the Berlin Senate and the Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg district support all residents or if they’re captive to monied interests. That’s because the two months’ deadline for exercising the right to pre-emptively buy a building (Vorkaufsrecht) in my Reichenbergerkiez expires today, 19 May. Back in mid-January, the local news radio reported that Reichenberger Straße is a perfect example of how long-term tenants are being forced out. In a story that’s unfortunately neither new nor exceptional, Inforadio described a building around the corner whose tenants are being priced out by modernizations made by the new owner: “Look at a map of the city and this street from above. You can practically make a Monopoly board out of it,” says Patrick Neumann, 43. “All the major real estate players who manage or sell or convert houses are represented here.” Like so many other private citizens, the freelance copywriter has had to become a tenant activist, fighting to save his building from being converted into condominiums.

On the very same block, the left-wing “alternative” Meuterei bar was evicted in early April with a huge – and costly – police presence. It wasn’t the same extremely violent scene as for Syndikat in Neukölln, but it was almost as bad. My euphoria over reading “Lause bleibt” (as I mentioned in February) has also evaporated with the realization that that’s a rallying cry – not the affirmation that the political and artistic initiatives, NGOs, craftspeople, families and communal flats in the old industrial property in the next block will be able to stay. (More to come.)

R108 lebt

But Reichenbergerstraße 108 (“R108 lebt!”) presents terrifying evidence that one group is replacing another here. Forgive me if these days I think more of settler colonialism than of “gentrification.” There are similarities. A few weeks ago, the Tagesspiegel weekly newsletter for Kreuzberg explained that the building (from 1986) had been sold to a firm in Hamburg that specializes in transforming ordinary flats into luxury apartments. In this case, the building’s 20 apartments are inhabited by people from Germany, England, Greece, Ireland, Lebanon, Morocco, New Zealand, North Macedonia, Poland, Singapore, Spain, Syria, Turkey, and Palestine.

In recent years I’ve been mentally noting all the imposing pre-war apartment buildings I pass on my bike, wondering if they’ve already been sold and are undergoing pricey modernizations – and sure that it won’t be long before they are. But the photo of the building at Reichenbergerstraße 108 shocked me: No distinguished Altbau, its weird shapes look unlikely to create any comfortable interior spaces. The oddly colored, graffitied building remind me of social housing in Paris. It totally shatters the model of what speculative investors have been buying. Why would anyone buy R108?

The following Saturday, as I approached the tenants’ sidewalk rally, I was thrilled to hear a woman addressing the crowd in Arabic. For me, that was a first. Although the event had been formally ended, a good 50 people were still milling around and being photographed holding bright signs: R108 lebt. To say that their building is full of life is an understatement. Kreuzberg’s Baustadtrat (Building Counselor) Florian Schmidt, who has promoted the district using its right to pre-emptively buy apartments to prevent tenants being evicted through expensive modernizations, was quoted by the Tagesspiegel: “If we don’t exercise our option to buy this building, no one will understand what that instrument is for.”

The building’s website explains that its international character means Berlin has to pre-emptively purchase the building to justify the city’s image as tolerant, international, and inclusive. Furthermore, the government’s stated aim of increasing social cohesion will be furthered by defending the building’s “tolerant and inclusive group of tenants”: If not there, then where?

Another argument pushing the city to exercise its right of first purchase relates to income. The investor has refused to sign an Abwendungsvereinbarung that would protect tenants from condo conversions and renovations that jack up rents. Most of the building’s tenants have modest incomes that make them especially vulnerable to the forces of gentrification. This is a social justice issue. Profit motives threaten to push out residents of modest means although Berlin’s governing program states that one of its key tasks in fighting homelessness and social exclusion is to ensure adequate affordable housing. Along with 23 adults, 20 children and teenagers also live in R108. An urgent appeal to the Berlin Senate from 20 local groups and numerous neighbors e explains: “For children and adolescents, displacement means the particularly painful loss of their familiar school environment and friends.” Rent increases and displacement risk impoverishing families at the same time that the city government says it is tasked to intensify “its efforts to combat family and child poverty.”

Case closed.

You would think.

However, when Hubert Trockenbrodt, one of the tenant organizers, escorted me to the rear of the building, I understood the real rub and true threat: Behind the kooky building designed by Johannes Uhl of “NKZ” fame (the sprawling apartment building that straddles Adalbert Straße at Kottbusser Tor), where the children once played stands an elegant new construction with 27 apartments and an underground garage. From the backyard of Reichenberger Straße 108, noise and exhaust from the new neighbors’ cars waft upwards to the apartments – instead of children’s voices. The kids now have to play in the street.

Along the new building and extending to the old brick wall at its rear is healthy, untrampled green grass and a small playground. New owners taking in that view from their spacious balconies will feel worlds away from the grungy, graffiti-smeared building that fronts Reichenberger Straße. They could well be in the suburbs! Tenants from R108 with whom I spoke have had no meaningful contact with their new neighbors: They meet only at the garbage bins. In Berlin, I know of no more glaring example of one social group replacing another. Crass!

Buy R108 now!

The Berlin Senate is reportedly buying fewer and fewer buildings pre-emptively – at the same time that fewer and fewer owners are agreeing to sign Abwendungsvereinbarungen to provide tenants temporary protection. The Berliner Zeitung quotes MP Cansel Kiziltepe saying that it’s about the Senate making available 320,000 € to top off the purchase price – less than the going price for a single apartment in the neighborhood. In a D Day press statement, R108 lebt announced to the perspective housing company owner that to help make the purchase more affordable, the tenants would forego renovations for 10 years. If only they can stay in their homes.

Riding my bike everywhere means that I haven’t been going through all the doors I see open in my neighborhood to explore the huge, deep blocks. But that’s key to understanding what is happening here. Last week, in one backyard I discovered three almost finished townhouses: A worker said that the three-story 200m2 attached homes (with cellars) will be rented for 3,000 € a month. Not far from there, behind a massive 10-story apartment block on Wiener Straße, another new building is nearing completion. There are no on-site developer signs, but my online research revealed condos for sale. And while I was looking, I found another large new home in a backyard in my kiez going for 1,345,000 €.

A study just published by the market research institute empirica confirms that in 2020, nearly two-thirds of all new rental apartments went for more than 14€/m2. Since 2012, the share of new apartments in that price range has quadrupled while the number of lower-priced rentals (max. 10€/m2) has halved. This is explained by the quintupling of the cost of land since 2010. The city’s good intentions – first made in 2014 – have been totally ineffective. Construction of new social housing (6.50€/m2 net rent) is way below target, and while private developers must offer 30% of their apartments at affordable rents, they are only for people with Wohnungsberechtigungsschein (WBS). Anyone who earns too much to qualify for a WBS but is not a big earner is left out in the cold.

With the steep rent rise of recent years attributed to the overall lack of apartments, the major issue is how to resolve that. The neoliberal mantra “Build, build, build!” is not going to help those who most need housing.

The new apartment buildings I’ve discovered near me look attractive and are set in fairly leafy backyards. But the “solution” of building inside blocks – Verdichtung (consolidation) – risks reproducing conditions reminiscent of Berlin’s infamous Mietskaserne (tenements). In Lichtenberg, tenants of a HOGOWE (city housing company) apartment complex dating from 1976 have been protesting the construction of 50 apartments in an area that once was green and shady. Residents only learned of the new building from the sound of saws felling their cherished trees – 55 in all. They fear being confronted by new walls – not nature – outside their windows. (That happened to me in New York.) One positive aspect of the building plan is that it includes no space for parking: According to HOGOWE, car ownership is unnecessary because the area is well served by public transportation. That’s fine – as long as good public transportation is easily accessible, and there’s secure, weather-protected storage for bicycles.

Berlin Autofrei

This brings us to a second referendum campaign that’s just getting underway: Berlin Autofrei aims to reduce the use of private cars within the S-Bahn ring through a law governing “road use based on the common good.” Air quality would be significantly improved, noise levels reduced, and pedestrians, cyclists, and other forms of transportation would be safer and have more space.

In recent years, Berliners have been counting the number of cars parked for very low fees or nothing at all (Whaaat?!) in their neighborhoods. I first heard about this activity in the North-Neukölln Schiller Kiez where volunteers calculated just how much space parked cars occupy: 6.5% of the kiez’s entire surface area! Playgrounds occupy merely 1.2% and green areas 1.5% – in a neighborhood where less than a third of its residents own cars. The Berliner Zeitung reports that 1.3 million private cars are registered in Berlin (population ca. 3.8 million). Try to get your head around that.

The land now occupied by parked cars could be used for playgrounds, schools, and while Berlin Autofrei doesn’t mention this, housing, too! Aware that improving the environment will cause more people to want to live in the city, the campaign website states: “A better life through fewer cars must not lead to rising rents and displacement. The social composition of neighborhoods that have fewer cars must be protected.”

We need not accept that the (perceived) scarcity of land for building means that Berlin’s extraordinary Tempelhofer Feld has to be nibbled away: We can contribute to climate protection and climate justice by building affordable housing in space now used for parking cars. Unlike the Mietendeckel, there is no question that the city has jurisdiction in this matter: German states (Berlin is a “city-state”) are responsible for laws governing public streets and roads. Furthermore, Berlin’s constitution makes the city responsible for protecting the environment. Like for DWE, in the first stage, the initiative has to collect 20,000 signatures (by the end of June) and then have it approved, before 7 per cent of eligible voters demand the referendum be put to a vote that could be held in 2023.

Changing Cities, Changing Berlin

In a similar vein to Berlin Autofrei are the kiezblocks: city neighborhoods that have no through traffic. Inspired by Barcelona’s “superblocks” and Dutch “compartments,” Changing Cities is working with residents of Ostkreuz and the Samariterkiez in Friedrichshain, as well as 12 neighborhoods in Pankow to reclaim public space by reconceiving the way streets are used. Last week, Karl-August-Kiez became the first model project in Charlottenburg.

In late April, “Cities for Rent: Investigating Corporate Landlords Across Europe,” a huge multi-author and multi-lingual study on the housing market in 16 major European cities, was published. The German text begins by remarking a strange and growing phenomenon: London evenings are becoming steadily dimmer due to the growing number of uninhabited apartments. This creepy development is financially worthwhile for their international owners: Even empty, they’re good investments.

Berlin is identified as an indicator of developments in the European housing market. While major differences exist, all 16 cities suffer the growing presence of international mega-housing corporations and market forces – and clueless politicians. In most of the cities, the populations have increased since 2010, as have housing costs. In Berlin, though, housing costs have risen higher: 64 per cent for existing apartments and 51 per cent for new flats. A lack of figures makes it impossible to make exact comparisons, but on average, European city rents have risen (just) 14 per cent and purchasing prices 26. The study presents tons of fascinating details, including the fact that between 2007 and 2020, more money was shelled out for apartments in and around Berlin than in London and Paris combined: 42 billion €, mostly by German investors. That’s changing, though.

Speaking of foreign investors… What’s Signa – the Austrian corporation that owns Karstadt on Hermannplatz – up to these days? It seems I see their signs everywhere: At the bottom of Schönhauser Allee, and near Klosterstraße… The 134m-high office building on Alexanderplatz has been granted a preliminary building permit: Construction should begin in summer. Although Signa claims their project fulfills “high energy standards,” in the Tagesspiegel of 18 March 2021, Ralph Schönball explains that “towers consume far more resources than normal buildings because of the complex construction, additional emergency exits and the higher proportion of areas exposed to the weather.” There’s also the Signa high rise planned near the Gedächtniskirche… and my Karstadt on Hermannplatz.

On 14 May, Signa announced that Karstadt will not be razed! Instead, Signa’s going to keep Karstadt’s original steel structure and add two floors and two 56-meter high towers… in wood. Project director Thibault Chavant claims the new plan will save 70 per cent more carbon emissions than conventional structures. Sounds like green-washing. It is not clear that the new project represents sustainable building – and in any case, it will still massively gentrify the neighborhood. Tell that to mayoral candidate Franziska Giffey, who praised Signa “for brilliantly taking into account all the concerns and fears.”

This brings us back to the crux: What sort of a city should Berlin be/become? When Signa was still planning to rebuild the original mammoth Karstadt building from 1929, Berlin’s Senator for the Economy, Ramona Pop, gushed about how that would attract tourists. Let’s go shopping! Giffey continues to regard the revised plan “as a measure to counteract online purchasing.” How likely is that?

As for tourists….

The violent evictions of Syndikat and Meuterei showed that tenant protesters are considered criminals. The eviction hearing rescheduled for the Kisch & Co. Bookstore in Oranienstraße (that I discussed in February) was finally held on 22 April – in a high-security courtroom. Only eight accredited journalists were admitted, and no one younger than 16. (The same was true for Potse, the popular youth center in Schöneberg, whose eviction has just been postponed.) MP Canan Bayram, who is fighting for commercial rent protection, was kept out.

The energetic and creative protest campaign of several years ended outside the Moabit criminal courthouse with a witty opera. Inside, just 23 minutes after the hearing began – that neither the mysterious owner(s), a real estate investment trust with an address in Luxembourg, or their lawyers attended – it was all over. In vain, Kisch & Co. lawyers claimed that, like residential tenants, small businesses should be protected from Berlin’s skyrocketing rents. I’ve since heard that the same investor has bought the two buildings across the street. How distressing. As for Kisch & Co., there is no point in appealing the decision: It would only be confirmed and an appeal cannot delay an eviction. (?!) While anxiously awaiting news of that date, bookstore owner Thorsten Willenbrock is searching for new premises in the neighborhood. Finding an affordable space measuring 140 m2 will be hard.

So much for one cultural site in my kiez. After surviving several owners and threatened evictions in the 30+ years since Köpenicker Straße 137 was first squatted, fears are mounting that the alternative housing project’s Wagenplatz (trailer site) will be evicted. While the owner’s plans remain unclear, the pressure is not: The price of the land has risen ten-fold in the past decade – to 6,500€/m2. On its website, “Köpi” research explains that the current owner owes 3.2 million € in back taxes to Zossen (a small city south of Berlin that offers the lowest corporate tax rates in Germany). Köpi staged a protest weekend on 15-16 May and plans a rally on the 25th. The trailer site’s day in court is 10 June. The district parliament (BVV) may manage to rescue it – but it won’t be easy.

Köpi research notes that evicting the queer/feminist housing project, Liebig 34, in October 2020 with 2,680 cops cost at least 1 million €. Add to that the cost of evicting Syndikat and Meuterei… “Does the city of Berlin really want to spend this amount of money on evictions rather than finding a way to protect alternative, self-organized spaces that offer immense value to the cultural diversity of a city?”

Art-washing

Berlin’s appeal has long been its alternative culture and spaces. For three decades, Köpi has attracted international artists, especially musicians, and visitors. Why destroy it?

Most probably because of greater financial rewards. Kunst Block & Beyond, a group of art and culture producers, addresses the fact that artists and art institutions have both unwittingly and knowingly allowed themselves to be used to market Berlin and improve the image of the real estate and tourist industries. Some sorely regret that. Others explain that they’d accepted the offer of a venue because they were pressed for time – and thereby embellished the image of another developer active in Kreuzberg. Pandion describes itself as “involved in the development, realisation and sale of high-class residential and commercial properties.” Near Moritzplatz, two large Pandion buildings are nearing completion: The “Grid” office building and “The Shelf.” The company’s English-language website says the latter offers a “total of 18,000 square metres [and] 680 […] as low-cost space for small businesses, art and culture.” The German page mentions just 221 m2. But the developer’s generosity is evoked in both English and German: “The existing buildings were handed over for temporary use by artists.”

Kunst Block & Beyond criticize artists’ involvement in neoliberal structures – in “art-washing deals.” The activists discovered that Pandion’s 250 million € project (two buildings totalling 28,000 m2) was co-financed by loans from a bank that was bailed out during the financial crisis with 13 billion € of taxpayers’ money. Before being sold for a pittance to a US private investment fund, the bank fired most of its employees. Kunst Block & Beyond point out that the same company, which in 2017 reaped 24.4 million € in profits (4 million € for the owner), is now encroaching on a neighborhood where 80 per cent of the children are poor, 55 percent of the population requires transfer payments, and unemployment is twice the Berlin average. They ask: “When a 250-million-€ private development is co-financed by a bank that was bailed out by taxpayers’ money, what is private and what is public?”

Pandion’s marketing and PR manager informed me by e-mail that, “with great effort,” a tenant has been found who will engage in “social mediation…also for the neighborhood” in the 221m2 space. (In response to my query regarding the size discrepancies in English and German, the English page has been corrected.) But the e-mail signature tipped me off to a new private “volunteer” initiative of Pandion, along with a real estate industry lobby, an asset management company, “property developers of high end residential accommodation in Berlin,” a company specialized in property sales and rentals, and one of Berlin’s “most successful influencer networks” – whose website features a photo of Berlin’s Senator for the Economy! To be invited to join the network, you’ve got to be a “boss” or a “creative,” over 21 years of age… and pay a yearly membership fee of 900 €. Transiträume Berlin exists to promote the use of temporary spaces for artists. Artists and cultural promoters: If you want a place of your own, don’t engage in (more) art-washing!

Gentrifying former refugee camps

As I write, loud sounds drift up from the street to my sixth-floor office. Traffic lanes in the street are being redrawn; behind the building I see trailers arriving. Construction of “Campus Ohlauer Straße” is finally beginning… on an historic site in the history of refugees in Berlin: directly in front of the old Gerhart Hauptmann School, which in 2012 was squatted by protesters evicted from their camp on Oranienplatz. Two years later, also under massive police presence (that I didn’t experience because I was traveling at the time), most of the refugees in the “self-governing” project were evicted. After that, a refugee hostel was opened – where I became friends with a family from Libya. (Rubina, the mother, finally managed to land an apartment that’s too small for five but much preferable to sharing a communal kitchen and bathroom.) Near me, according to its website, HOWOGE is constructing 120 apartments for refugees, students and low-income families, a residential community for homeless women with children, a day-care center, and a bicycle garage. Half of the apartments are subsidized. Only half? Which of these groups doesn’t need help paying rent? The concept and architectural plans have been changed many times. Mal sehen…

Unfortunately, the future of the green area at the Treptow end of Reichenbergerkiez is uncertain. Ratibor 14 is a bucolic business park that includes 20 wood and metalwork, car, bicycle and car workshops, a Wagenplatz, a playground, and Jockel Biergarten. Next door is a day-care center for 200 children. But the city has decided to use the land to build a five-story modular collective accommodation (Sammelunterkunft) for 250 refugees in “concrete high-speed construction” (Beton-Schnellbau) – a housing model that has been widely dismissed in favor of decentralized housing for smaller groups of refugees. Ratibor 14 has nothing against refugees, but they want them to be properly housed and reject having two vulnerable groups played off against each other – especially in service of the long-term aim of gentrifying the area. In an article by Tim Zülch in Neues Deutschland from June 2019, a metalworker and activist from Ratibor 14 views the involvement of Berlinovo (in the business of furnished apartments, an important contributor to rising rents – see my first article) with misgivings: “We expect the simplified procedure for building refugee accommodation will be used to convert the MUF [modular housing for refugees] on the Ratibor premises into lucrative furnished apartments for students or other groups as quickly as possible.” Two years later, there’s no news.

To be monitored: Housing for refugees and the future of Wagenplätze.

Get active

With the rent cap overturned, the need for real solutions to the crisis of unaffordable rents is more pressing than ever. Here are a few opportunities to express your concerns:

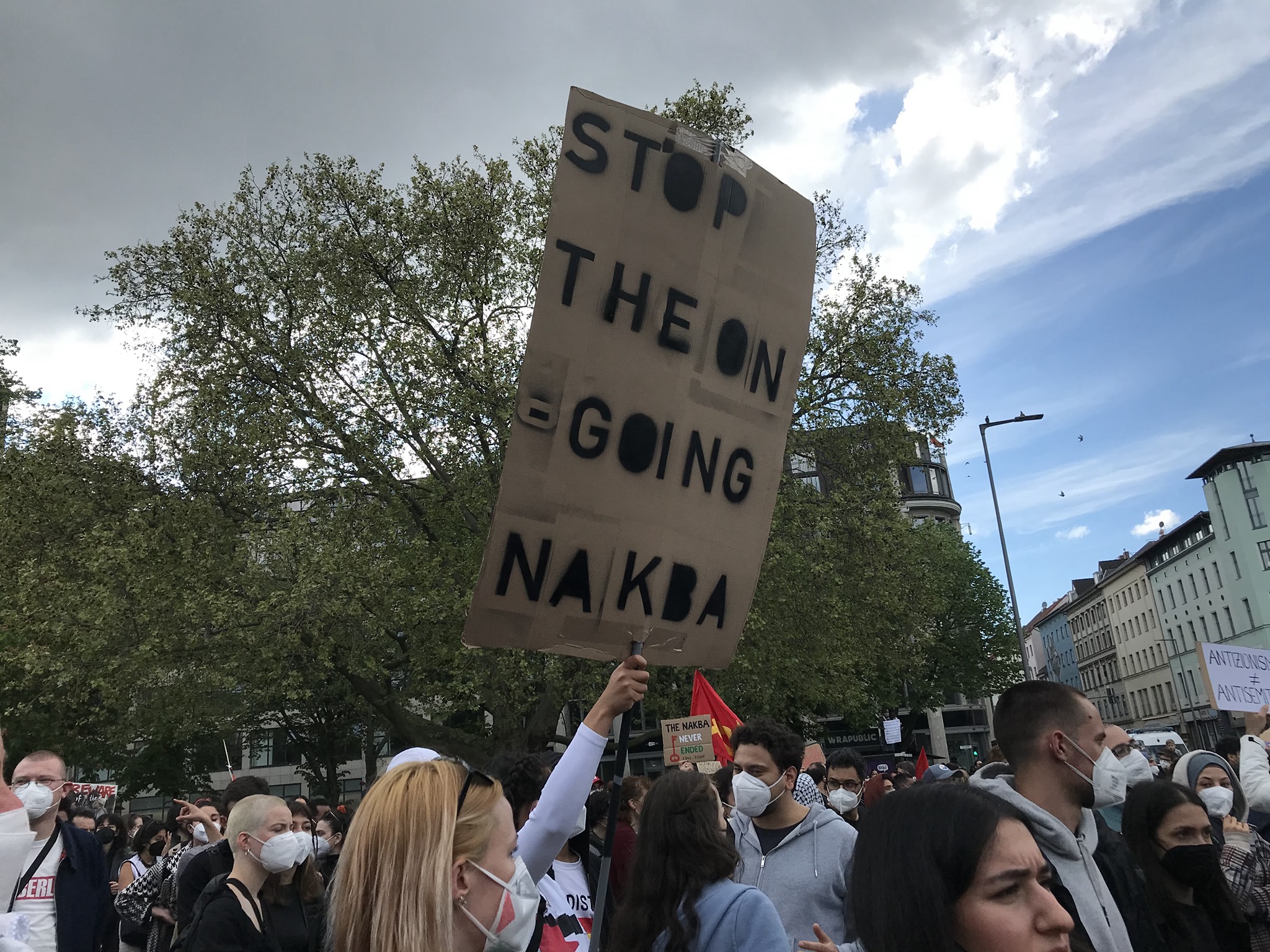

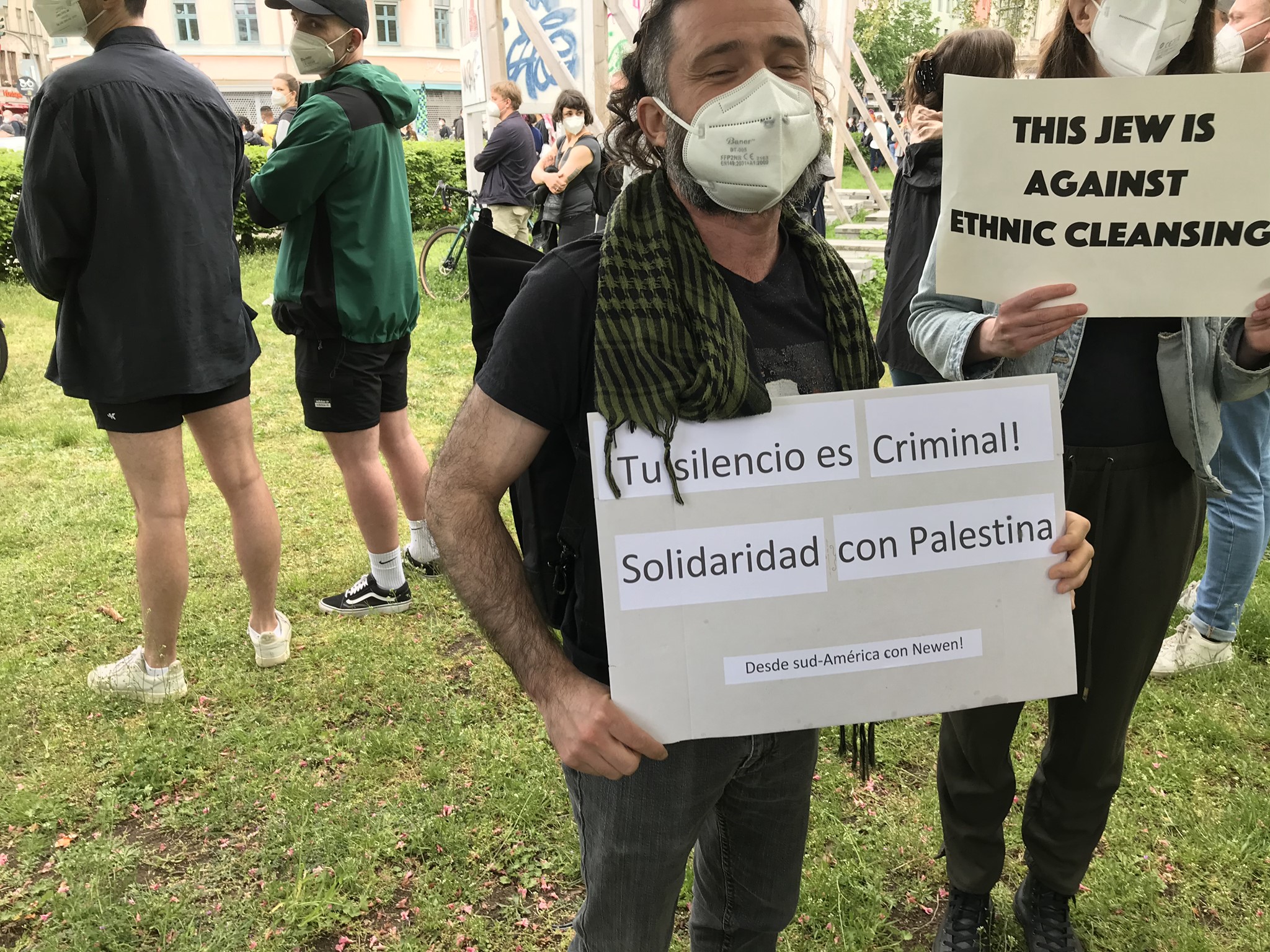

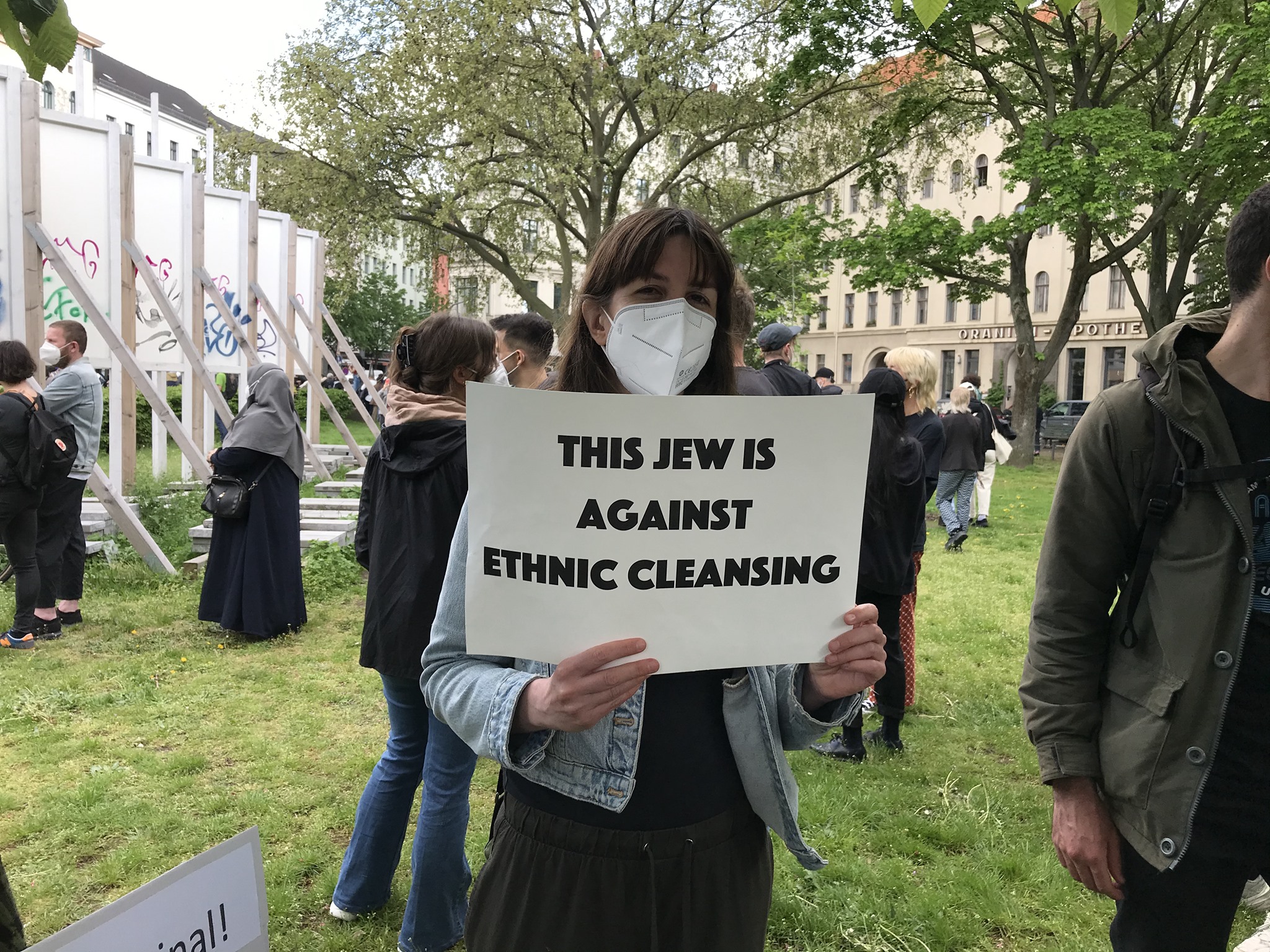

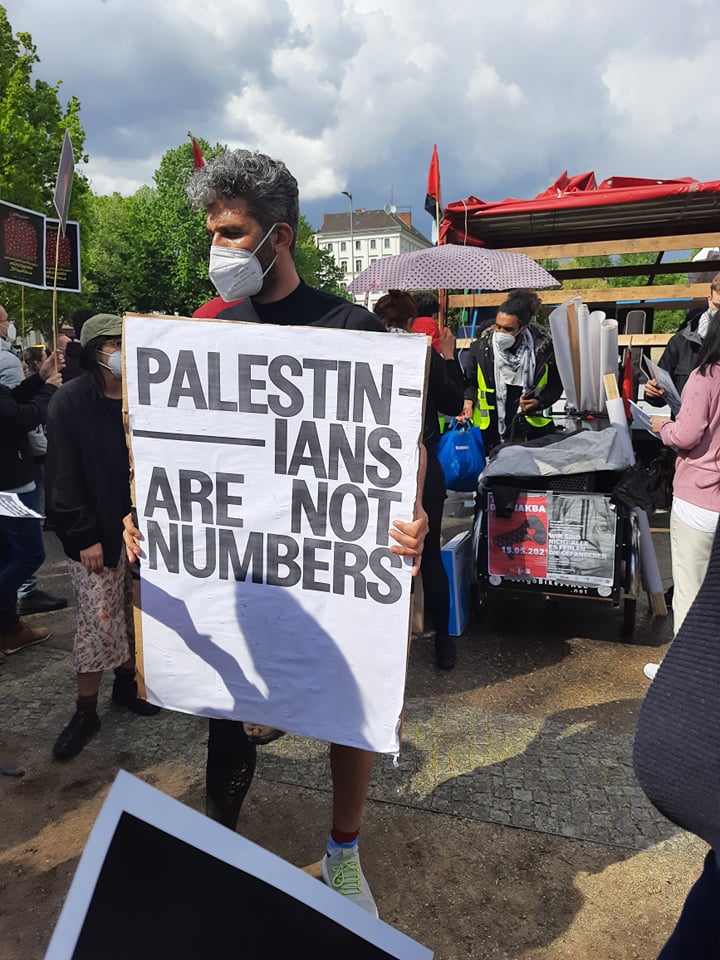

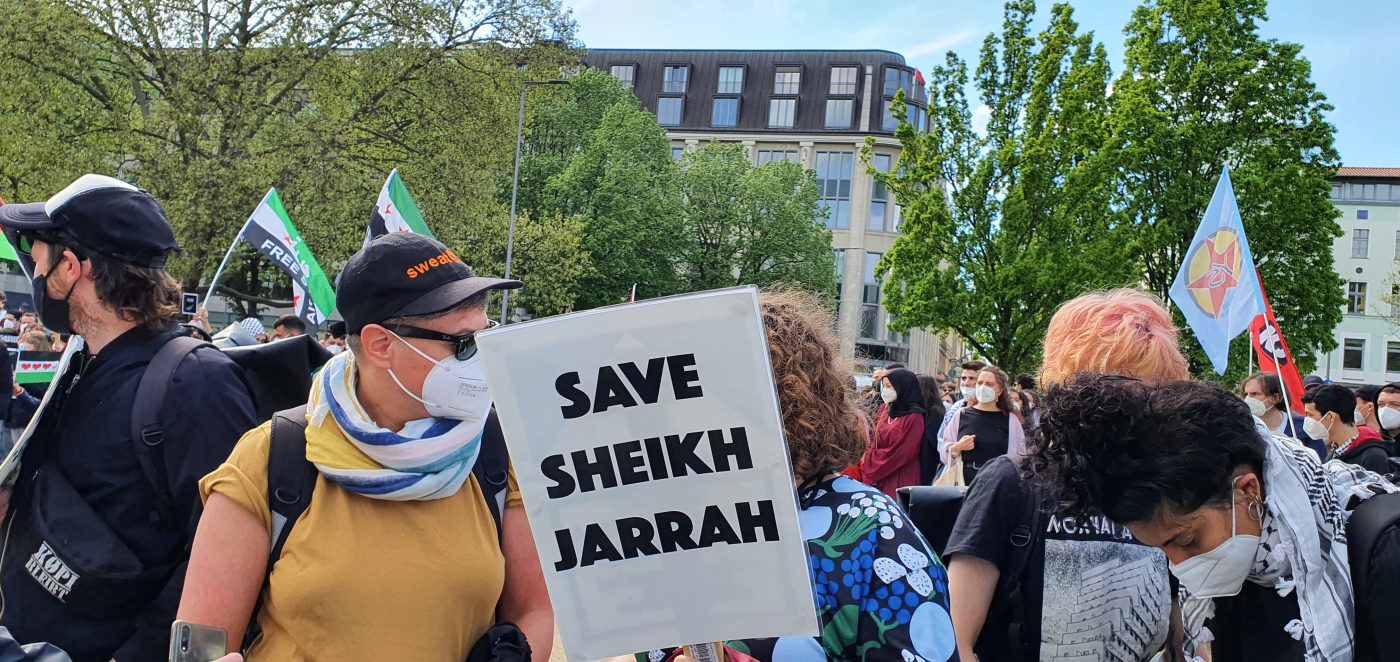

On Sunday, 23 May, the Gegen Mietenwahnsinn – Jetzt Erst Recht! (Fighting Rent Madness – Now More than Ever!) demonstration starts at 1 pm on Potsdamer Platz. Principle demands include commercial rent protection to protect neighborhood bookstores and bars, late-night stores (Spätis), and the like from being replaced by cookie-cutter chains and big companies, as well as a rent moratorium and the waiving of arrears. Bring your face mask and pot lids!

(On the demo flyer, I’m thrilled to read the address of the person responsible for the press: Lucy-Lameck-Straße! The street that once commemorated a German colonialist who brutalized Africans resisting his murderous policies now honors the first woman minister of Tanzania.)

On Saturday, 29 May, there’s a “Right 2 the City for All” rally at Tempelhofer Feld at 3 pm: “Voting rights for all, housing for all, right to the city for all.“ Organizers say the demo aims “to politicize the lack of representation in the DWE referendum for those without a German passport and highlight the discrimination that migrants and racialized Germans experience in the housing market.”

At 2 pm on 29 May, the Parkplatz Transform initiative is holding a demonstration on reducing the number of private cars in the city center. Details to come here.

PS. In the morning after Day D, I again check online for news of Reichenbergerstraße 108 – and discover that one of the apartments in the new rear building (108a) is for sale: 600,000 € for 93m2! Still no news of the fate of R108.

Finally, at 4 pm, I find the sad news: All our fervent hopes and vigorous efforts were in vain.

Wirtschaftlichkeit trumps Menschlichkeit yet again.

©Nancy du Plessis 2021