Introduction: Hallo zusammen. Vielen Dank, dass ihr mich heute Abend hierher eingeladen habt, um über das Buch zu sprechen, das ich gemeinsam mit Donny Gluckstein geschrieben habe. Ich freue mich sehr, hier in Berlin sprechen zu dürfen.

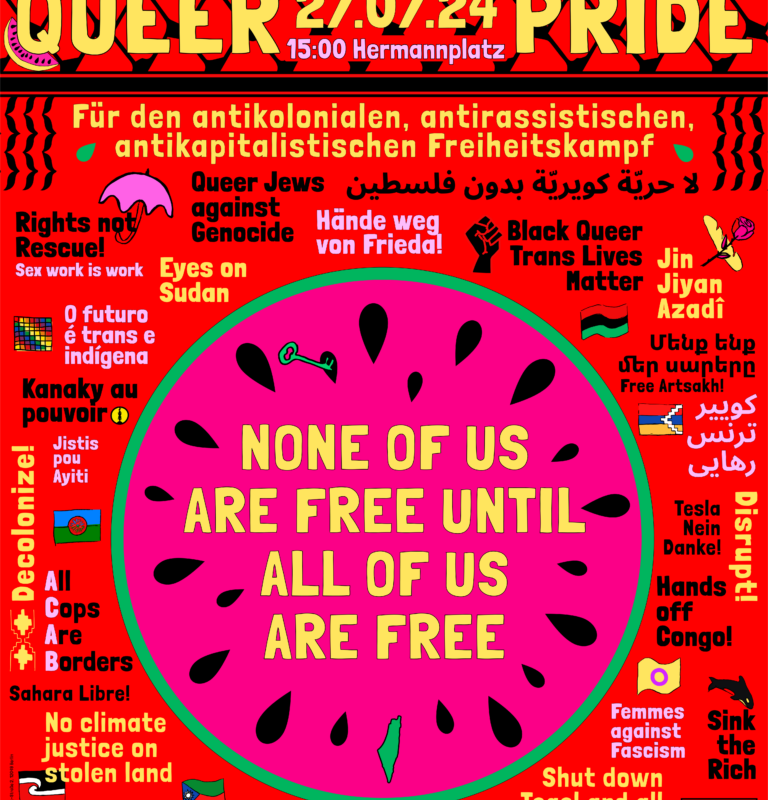

Berlin has become a centre of support for Palestine and developed an alternative position as to what is Antisemitismus und Antizionismus. A look at German history shows this is an actual theme of it.

Und ich bin auch hocherfreut, dass ich alles teilweise auf deutsch sagen kann, da ich schon lange deutsch lerne. Ich spreche jetzt auf English und zum Schluss komme ich noch einmal auf Deutsch zurück.

To start off with – I’m a Jewish Australian. A large part of my mother’s family emigrated to Australia in the 1930s from a small town in Poland. Every single family member who remained behind died in the Holocaust. So I’m not a holocaust survivor in the formal sense, but my existence is marked by that event.

I am a life long socialist, and I’ve been an active anti-Zionist almost all my adult life. I’ll by talking about why a book like this matters today. The book ends in 1948 – 80 years ago. Perhaps some people might think this is a niche history – interesting but not important today.

But history matters because the battle for memory is also a battle for the present.

The Zionists constantly invoke Jewish history as a justification for their support of Israel, so an alternative view is very immediate and urgent. The Zionists don’t want us to know there is a different answer to antisemitism than the Israeli state.

Our book brings together a range of material and information available but scattered in many places. We trace antisemitism, modern Jewry and Jewish political currents; moving to Jewish radical history, focusing on Russia and Poland; the and Jewish in emigration to London and New York. We then discuss Nazism in Germany, the Holocaust and how Palestine impacted the radical Jewish tradition.

We introduce at the beginning the “lachrymose (or tearful) conception of Jewish history”. Or the idea that the main element of Jewish experience has been suffering, it’s always been so and can’t be changed. In other words, Jews are eternal victims.

There are three ways to respond to this idea. Firstly, you can say we can’t do anything about antisemitism, so we withdraw into our own ghettoes, customs and religion, we do nothing, and remain victims. The second option is to change from a victim by joining the perpetrators: become an exploiter and an oppressor yourself.

Zionism combines both of these. They start saying that we can’t do anything about antisemitism and non-Jews will always be antisemitic. But then they say victims must to take lessons from the colonialists, imperialists, the ruling class and even the antisemites. Let’s set up our own state and become just like them.

But there is a third option. In this book, Donny and I show that while the oppression and suffering are certainly there, it’s not true that Jews are nothing but victims. They have always resisted and fought back. The radical tradition is the history of working class and socialist Jewish struggle against both antisemitism and their position at the bottom of society. Against both oppression and exploitation. It’s the tradition that says we can fight to defend ourselves. The tradition that knows what antisemitism is, but doesn’t accept it as eternal or plan to go somewhere to set up oppress someone else. And this tradition has historically been entwined with the working class and socialist movements.

Most people have heard about some parts of this story. Everyone knows about the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and the Battle of Cable Street in the East End of London 1936. Many are aware of the 1908 strike of mainly Jewish women garment workers in New York, known as the uprising of the 20,000.

But these are usually treated as one-off events. I asked myself, where did these mass actions come from? Things like that don’t just come out of the blue. I was simply astonished at what I hadn’t previously known about. realised these were just the peaks of a movement with connections over at least 6 decades over continents.

This book rediscovers this history to set it in the context of what antisemitism is, and the role of Jews in the socialist and radical movements between the 1880s and 1948.

This was a very exciting journey. I want to take you on some of the stops on that journey and some exciting and inspiring stories.

Tsarist Russia

One of my first discoveries was that Jews had fought back against pogroms in tsarist Russia. Previously may image was of frightened Jews huddling in synagogues. But there were armed self defence groups, led by the Jewish Labor Bund but also with other socialists and leftists involved, Jews and non-Jews.

The Bund put out a call for armed self-defence after a horrific pogrom in Kishenev in 1903: “[W]e must come out with arms in hand, organise ourselves and fight to our last drop of blood. Only when we show our strength will we force everyone to respect our honour.” And a year later they were able to say “There are no longer the former, downtrodden, timid Jews. A new-born unprecedented type appeared on the scene—a man who defends his dignity.”

The self defence groups were led by the Bund in coalition with radical and socialist groups. They didn’t see the issue as just about Jews. What they said was that the struggle against antisemitism was “also directed against the ruling class and for socialism. Thus the two struggles were one”.

And they enjoyed successes. For instance in 1906 in Bialystok in Poland they completely protected major working-class sections of the city: “At every corner of the poor section of Bialystok, patrols of the Jewish Self-Defence League were stationed with revolvers and grenades… They guarded the streets and fired warning shots into the air. If a gentile went by carrying loot, they would frighten him until he threw down the stolen package and fled”.

A very different picture to huddling in the synagogue.

Migration to the West

Nonetheless pogroms continued. Poverty and misery of life in tsarist Russia led hundreds of thousands of Jews to emigrate including to the UK, the US.

In the US almost continual struggle in Jewish areas of New York occurred from the late 19 century until WW2. Jewish men and women fought the bosses and the state with the support of socialist organisations.

Early on there was strike after strike as Jewish workers fought to establish trade unions. After the turn of the century, activity moved into the community. In May 1902 an increase in the retail price of kosher meat outraged housewives and a crowd of 20,000 women set out.

One newspaper reported that “an excitable and aroused crowd [mostly of women] roamed the streets…armed with sticks, vocabularies and well-sharpened nails”. The police attacked but they didn’t have it all their own way—one woman retaliated by slapping a cop in the face with a moist piece of liver!

When the issue spread to Brooklyn, the New York Times had this headline: “Brooklyn mob loots butcher shops. Rioters, led by women, wreck a dozen stores. Dance around bonfires of oil-drenched meat piled in the street—fierce fight with the police”.

The Times ended by calling for the repression of this “dangerous class…especially the women [who] are very ignorant”.

When a magistrate asked one woman why they were rioting, she replied: We don’t riot. But if all we did was to weep at home, nobody would notice it”.

Once more – the falsity of the lachrymose or tearful conception.

The meat boycott was followed by a series of rent strikes again led by women. And then the community action fed back into the workplace in 1908 with the Uprising of the 20,000. Female Jewish garment workers went on strike over piece work rates and other issues.

Leading up to the strike, socialists called a large parade on a date honoring an 1857 demonstration of New York garment workers, which police had attacked and dispersed. The 1908 demonstration was so successful that German socialist Clara Zetkin proposed an International Working Women’s Day in 1910. This has continued ever since.

So when talking about the Jewish radical tradition – we commemorate the real heritage of International Working Women’s Day which is Jewish, internationalist, socialist and working class.

Now I head over to London where in the East End, conditions were indescribable. Many Jewish socialists understood how important class was here. Many bosses and landlords in the slums were also Jewish and synagogues generally preached acceptance. As one early socialist in the East End said:

“The underlying class struggle exists also amongst Jews… Therefore Jewish workers must unite among themselves against the other spurious unity—that with the masters!”

The early Jewish radical movement in London is full of stories about all sorts of currents – anarchists, socialists, early trade unionists, Marxists and many others.

The leader of the anarchists was a German Rudolf Rocker, who wasn’t Jewish. But he learnt Yiddish and threw in his lot with the Jewish East End. They set up a club which became a centre for radical and trade union activities throughout London. It was particularly important during strikes. It also provided premises for a Jewish socialist newspaper, and was an educational, social and cultural centre as well. They welcomed everyone – Jews and non-Jews, young and old, men and women. Above all it was a centre for political debate and argument.

The Jewish anarchists were very much “in your face atheists”. They ostentatiously ate ham sandwiches outside the synagogue on Yom Kippur the most important fast day of the year. Perhaps this was a bit sectarian. But we should remember atheism was as an important political topic then.

Over decades the workers struggled against the sweating system and their appalling working and living conditions. But not alone. In 1889 the Jewish tailors went on strike and received a large donation from dockers.

Then in 1912, during a major dock strike, Jewish families took in and cared for dockers’ children helping the dockers to stay out on strike. And then 24 years later in 1936, the dockers again returned the favour and constituted the militant vanguard of the mass demonstration at Cable Street.

One of the participants, Bill Fishman described it: “I was moved to tears to see bearded Jews and Irish Catholic dockers standing up to stop Mosley. I shall never forget that as long as I live—how working-class people could get together to oppose the evil of fascism.”

So Cable Street didn’t come out of the blue. I was also very excited to discover another movement at the same time which fed into the resistance to the fascists. That was the tenants’ movement which carried out rent strikes in the same period.

One of the leaders said this: “It was a genuine united movement of the people, drawing together Jews and Christians at a time when antisemitic propaganda was being stepped up, helping to isolate and expose both fascists and right-wing local Labour leaders.”

Let’s move back to Europe. The “lost world” of Jewish life in interwar Poland is very often invoked with nostalgia – the romanticised shtetl (small town) focusing on food, family warmth and traditional customs. But there is another side to the story.

Arnold Zable, an Australian refugee activist and writer, describes his trip to Poland to meet people of his parents’ generation. He says:

“Stories survived, countless tales of partisans and revolutionaries, resistance fighters and firebrands engaged in a fiery struggle.”

From Arnold’s words I got the idea for the sub title of our book: ‘Revolutionaries, Resistance fighters and firebrands‘. With rising antisemitism in Poland in the 1930s, the Bund again set up self defence groups.

Today, the Jewish working class says to the fascist and antisemitic hoodlums: the time has passed when Jews could be subject to pogroms with impunity… Pogroms [will not] remain unpunished.

The Bund didn’t want confrontations between Poles and Jews but between fascists and anti-fascists. So they deliberately drew in non-Jewish workers. The Bund and the Polish Socialist Party collaborated over Mayday parades and held general strikes against pogroms and antisemitic attacks. That cooperation built up over many years habits so when the nazis invaded in 1939, thousands of Jews found a hiding place in the flats of non-Jewish workers.

And this brings us to the war and the Holocaust and the worst of the myth of Jewish passivity – that Jews went to the concentration camps like sheep to the slaughter.

But there were underground resistance movements in approximately 100 ghettos and armed uprisings in 50. There were also uprisings in 21 concentration camps and approximately 50 Jewish partisan groups. About 10,000 people survived in family camps in the forest.

Forced labourers in shoe factories sabotaged by putting nails in boots and tailors sewed left arms into right armholes of coats and vice versa. The united underground organisation in Minsk had a culture of solidarity between Jews and non-Jews. It ran a clandestine press, smuggled children out of the ghetto and helped 10,000 to escape to the forest, most of whom survived the war.

There are so many more stories I could tell you, but if I told you all of them you wouldn’t buy the book! So I will end with this – the women couriers who maintained communications between the ghettos.

They smuggled people, cash, fake IDs, underground publications, information and weapons. They hid items in their clothes, their bras, in sanitary towels, in their shoes, in sacks of potatoes. They smuggled guns in loaves of bread and coded messages in their plaited hair. Most of these women were members of Jewish socialist youth groups or communists. Yet they are virtually unknown.

So my last story is about a communist Niuta Teitelbaum – blonde and blue eyed and looking like a naïve young Polish teenager. But as an assassin she used to walk openly into the offices or homes of gestapo officers and shoot them in cold blood. One day she strolled up to the guards outside a gestapo prison, feigned shame, and whispered that she needed to speak to a certain officer about a “personal matter”. The guards assumed that she was pregnant, and they politely showed her the way. Once in the officer’s room she pulled out a concealed pistol with a silencer and shot him. On the way out, she smiled meekly at the guards who’d let her in.

The couriers endured prison, rape, humiliation and beatings and kept on fighting. The astonishing bravery, intelligence, resourcefulness, drive, determination and self-sacrifice of these women fully destroys the myth that Jews “went as sheep to the slaughter”.

I’m now going to wrap up and end in German. The following translates the German spoken words:

I want to say how exciting and inspiring I find this whole history – a Jewish radical tradition, a tradition of socialists who fought back against oppression and exploitation, a history of resistance and of the struggle to change the world. A history of people who didn’t just weep and hide away, who refused to be just victims or to join the oppressors. This history has been a joy to rediscover.

But this history doesn’t just belong to Jews. It belongs to all of us here in this room, and to all of those who are engaged in struggle against the horrors of our society, of oppression and exploitation and of war. This isn’t an academic or a sectional history but is avowedly partisan, a history to support and inspire struggle.

So I want to end with the words of Marek Edelmann, a Bundist and participant in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. After the war Edelmann went back to Poland and remained a radical all his life. During the second Palestinian Intifada Edelman wrote a letter to the Palestinians. He compared them to the Jewish Fighting Organisation that had led the Warsaw ghetto uprising. He addressed it to “commanders of the Palestinian military … to all the soldiers of the Palestinian fighting organisation”.

Just as Edelmann linked the resistance fighters in Warsaw, so do I link the Jewish radical tradition with today’s fight of the Palestinians against expropriation, persecution and genocide. I stand with Palestine. I hope the book that Donny and I have written will contribute to the ongoing struggle for their freedom and for the freedom of all of us.

As Milan Kundera says:

“The first step in liquidating a people is to erase its memory. Destroy its books, its culture, its history. Then have somebody write new books, manufacture a new culture, invent a new history. Before long that nation will begin to forget what it is and what it was… The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.”