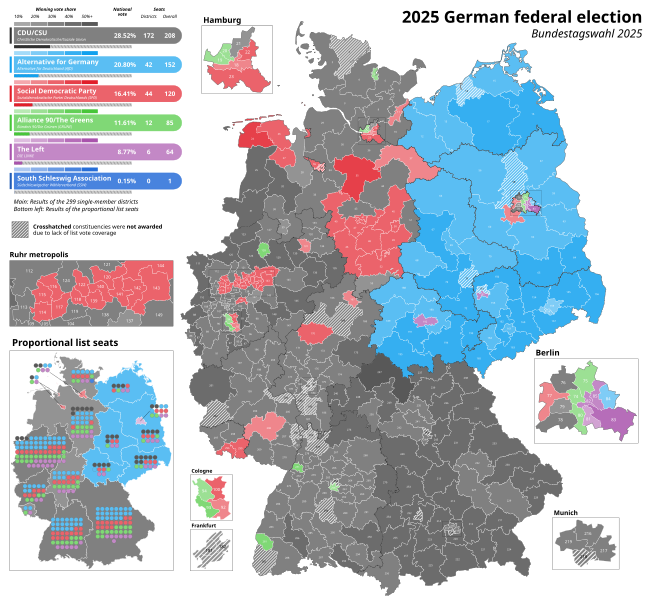

A federal election will be held across Germany on Sunday, 23 February. This will elect 630 members of the Bundestag.

The German electoral system gives each voter two votes. The first is to directly elect a candidate in their constituency — first past the post, regardless of how their party performs overall. This ensures that every constituency is represented in the Bundestag. The second vote is for a party’s electoral list. It determines the parliamentary group or coalition that has a majority, and is able to elect a candidate as the Federal Chancellor.

To enter the Bundestag, a party must either get five percent of the nationwide second vote, or an FPTP win in three constituencies. Parties receive seats in the Bundestag in proportion to their national share of the second vote.

We have gathered some of the highlights from each party’s programme and what they are proposing, divided across different categories.

The Left

Die Linke

Die Linke (The Left) was founded in 2007 and is Germany’s biggest left-wing party, part of the The Left in the European Parliament. They advocate for democratic socialism as an alternative to capitalism. In the last elections, they got 4.9% of the votes. Some of the highlights from their programme are making life affordable, treating housing as a right and not as a luxury, enacting effective climate policy and tackling millionaires. They have also published a short programme in English.

Economic policy: Die Linke, critical of the rise of the cost of living in recent years due to the Ampel-Koalition, want to regulate and limit prices — for example, by scrapping the VAT on basic food products.

Salaries & pensions: Die Linke want to reform the income tax, with anyone earning less than €7,000/m (gross) paying less tax; all taxable income below the minimum subsistence level of €16,800 euros per year would remain tax-free, and the party would reintroduce the wealth tax for millionaires and billionaires. They want to increase minimum wage to €15, and to allow anyone that has worked for 40 years to be able to retire. They also discuss work-life balance, and defend a reduction in working hours with full compensation, in a “near-full-time part-time” model.

Housing: for Die Linke, affordable housing is the central social issue of our times. They advocate a nationwide rent cap — which would involve a ban on rent increases for the next six years, and apply hard upper limits on rent increases. Besides this, they want Eigenbedarfe — the terminations of housing contracts for personal use — to be restricted to first-degree relatives. They want to simplify the process to access housing benefits and prohibit electricity and gas cut-offs. Real estate companies with more than ten apartments would be expected to set up tenant advisory councils, and invest €20 billion per year in non-profit housing. They support the Deutsche Wohnen & Co. Enteignen campaign.

Transport & mobility: Die Linke want to scrap the VAT on buses and trains, reduce the price of the Deutschlandticket to €9, and make it free for children, students and senior citizens. They want more staff for public transport, with better pay and working conditions. They also want to bring back the privatized local transport companies into public ownership.

Health: Die Linke want a health insurance scheme that “everyone pays into” — reducing the contribution from 17.1% to 13.3%, abolishing the contribution assessment limit, and with reduced contributions for people with a monthly income of less than €7,100 (gross) per month. They want health insurance to cover access to dentists and opticians.

Climate: Die Linke intend to support employees who want to take over a business to run it as a co-operative, through an investment fund for industry. They want to ban food waste and give away edible food to non-profit organizations, introduce a speed limit of 120 km/hr on motorways and 30 km/h in towns (outside main roads). They want a ban on private jets and megayachts over 60 meters. They want to introduce a frequent flyer tax, over a flat-rate additional tax (CO2 price).

Education: Die Linke want free lunches in kindergartens and schools, and both free and paid childcare centres from the first year onwards. They want to improve the recognition and qualification of immigrant teachers, and create a reserve of up to 10% in teaching and educational staff.

Feminism: Die Linke defend equal pay for equal work, and a provision in the electoral law that requires 50% of the list in public elections to be allocated to women. They defend the deletion of Section 218 and want abortion considered part of healthcare, as a medical procedure. In terms of measures for violence against women, they want to implement the legal right to accommodation in womens’ shelters. They also want to bolster the right to gender self-identification.

People with disabilities: Die Linke intend to implement binding regulations in the General Equal Treatment Act and the Equal Opportunities for People with Disabilities Act. They wish to raise the obligation to employ people with disabilities to 6%, seeing as the unemployment rate amongst this group is twice as high as in the general population. They want to restructure special needs schools and employ special education staff in regular schools.

Migration: Die Linke want unrestricted work permits for people with refugee status from the day they arrive in Germany. They wish to dissolve FRONTEX and replace it with a civilian European sea rescue program. They intend to stop the criminalisation of civil society sea-rescue organisations.

Military, foreign policy & EU: Die Linke are in favour of a ceasefire in Ukraine, and in Israel and Palestine. They want the end of German arms exports to Israel, and the recognition of Palestine as an independent state within the 1967 borders. They are against the reintroduction of conscription. They oppose further rearmament of the EU and its militarization, and want Germany to join the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. They want to ban advertising for the Bundeswehr in schools and universities. When it comes to the UN, they want to reform it, with stronger decision-making powers to the General Assembly compared to the Security Council. In terms of the EU, they call for an adjustment of the deficit and debt rules, and strengthening the trade union rights through the Minimum Wage Directive.

Ferat Koçak, the Linke candidate for Neukölln, has published an article called “Free Palestine” here.

MERA25

MERA25 are part of the Democracy in Europe 2025 (DiEM25) European movement. As part of this movement, MERA25 was founded and ran for the first time in a German parliamentary election in 2023, for the Bremen parliament. Their programme identifies the priorities of human dignity and economic justice, ecological change, social security, peace, open borders, and a democratic Europe; it was also released in a shorter version in English. In this election, they are running in Berlin, Bremen and Nordrhein-Westfalen.

Economic policy: MERA25 propose an increase in government spending for social, environmental and economic reasons, and to democratise the euro by placing monetary policy entirely in the hands of elected parliaments. They want a “complete overhaul” of the social system, with care and social security for all.

Salaries & pensions: MERA25 want state pension guarantees to abolish old-age poverty. They intend to use automation and AI to gradually reduce the statutory working hours from 40 to 30 hours per week. They want to introduce a European unconditional basic dividend as a first step to an unconditional basic income, abolish the value-added tax, and reform inheritance tax laws that currently guarantee tax exemption for the wealthy.

Housing: MERA25 defend the expropriation of large housing groups, and for the management of housing to be made by democratic tenant participation. As such, they support the Deutsche Wohnen & Co Enteignen campaign. They want to convert existing housing stocks into social housing, and strengthen the legal certainty of preemption rights for municipalities.

Transport & Mobility: MERA25 want affordable, friendly, supra-regional and free mobility. They want to examine options to avoid traffic in the first place, before thinking about shifting it — such as through using urban and regional planning to prevent the designation of new building areas in peripheral locations, and providing incentives to move into existing houses. They want the right to work from home for all professional groups who can do so.

Health: MERA25 want to ensure that hospitals and other health service providers are exclusively state-run, replacing all statutory and private health insurance with a state-financed health system. They aim for 100,000 new nursing jobs in the medium term, with wages and working conditions set in mandatory, nationwide tariffs.

Climate: MERA25 puts a big emphasis on a Green New Deal in order to achieve climate neutrality by 2030 at the latest. They want to establish a circular and regenerative economy, completely stop subsidies on fossil fuels, and believe in a fundamental right to self-sufficiency with renewable energy. They want to reduce air traffic to the bare minimum and tax kerosene, as well as to end factory farming in Germany.

Education: MERA25 want to create a nationwide offer of all-day schools with free meals. They want to expand further education programmes for all age groups, especially in the area of digitalisation. They want more critical anti-racism education in schools, and more youth work.

Feminism: MERA25 want toextend the Equal Treatment Act, close the gender pay gap, and defend gender self-identification, though they don’t mention how. They want to recognise parental rights for same-sex couples.

People with disabilities: MERA25 reject ableism in all its forms.

Migration: MERA25 want to stop the detention of immigrants in closed reception centres. They want to end the differentiation between “political” and “economic” migrants, create a common European asylum procedure that guarantees fundamental rights, and top deportation under the principle that every person has the right to move freely. They want to abolish FRONTEX and use its resources to launch a European search and rescue mission in the Mediterranean.

Military, foreign policy & EU: MERA25 are in favour of a “pan-European security architecture”, with the objective of joint disarmament. They want Germany to join the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons and a complete withdrawal of the arms industry from the German export economy. They want an arms embargo against Israel, and for Germany to recognize Palestine as a state. They support a “long overdue reorientation of Israel-Palestine policy”. In terms of policing, they want a reform of the Polizei to raise awareness and prosecute violence and discrimination by security authorities. They defend the abolition of the practice of racial profiling. When it comes to the EU, they want to abolish the debt brake and put an end to European debt rules. Under their policies, lobbyists from multinational corporations would be banned from parliaments, and international funds would be used for reparations for colonial crimes. As for the UN, they intend to replace its Security Council with a democratically elected body with “representatives of the world’s regions or continents”.

RIO & RSO Alliance

The Revolutionary Internationalist Organization (RIO) and the Revolutionary Socialist Organization (RSO) have agreed on a common programmatic platform. They are running for the first time in two constituencies in Berlin (Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg – Prenzlauer Berg East and Tempelhof-Schöneberg), and one in Munich (Munich-West/Mitte) as independent socialist candidates, with the priorities of declaring war on growing nationalism and racism, rearmament and warmongering, and a commitment to the self-organization of the working class and youth, independent of all established parties.

Economic policy: they have 14 proposals for an anti-capitalist and socialist alternative.

Salaries & pensions: their proposals include ban on layoffs and expropriation without compensation of companies that carry out mass layoffs and closures, reduction in working hours without loss of wages, equalization of wages and working hours in East and West, incomes at a minimum of 2,000 EUR net and linking wages, pensions and social benefits to price increases. They support a four-day week with full compensation.

Housing: they defend public investment in housing, reducing rents, expropriating housing corporations and banning housing speculation.

Transport & Mobility: they support free public transport, and the abolition of the CO2 tax.

Health: they support public investment in health, nationalization of all clinics, abolition of the two-class insurance system, and the full assumption of health costs by the state.

Climate: they support the nationalization of large-scale industry and the ecological conversion of the coal and car industry. They want a ban on climate damaging investments, and the achievement of climate goals without job losses.

Education: they defend the need for sufficient daycare and school places, training for educators and teachers and smaller classes, as well as free meals for all educational institutions.

Feminism: they mention equal pay for equal work, and intend to abolish Section 218, expand sex education and free contraceptives, menstrual products and pregnancy tests.

People with disabilities: they want complete state support for people with disabilities, instead of family-driven care. They support wage increases up to the minimum wage level.

Migration: the socialist candidates advocate for active and passive voting rights for all people living in Germany, open borders and the acceptance of all refugees with full rights to decentralized housing, healthcare, education and work. They also mention safe escape routes instead of FRONTEX. Abolition of the residency requirements and payment cards.

Military, foreign policy & EU: they demand disinvestment from the Bundeswehr, and for all Bundeswehr abroad to immediately withdraw. They want to close the Ramstein US Air Base. They appeal to blockade actions by the workforce against German arms deliveries, and demand an end to Germany’s military support for Israel, as will as the lifting of bans on left-wing and Palestine-solidarity organizations. RIO/RSO are against the IHRA definition of antisemitism. They wish to abolish the new military service, and are against conscription. They want both the Russian army and NATO out of Ukraine, and to dissolve NATO.

Nathaniel Flakin has written an article on TLB about these independent candidacies.

The Bad, The Bad and the Ugly

SPD

The Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (Social Democratic Party of Germany/SPD) are Germany’s oldest political party, founded in 1875. The SPD are the head of the currently governing Ampel-coalition, alongside the Green party and the FDP. They have been governing since 2021, under the leadership of Olaf Scholz. The SPD’s current programme includes a strong focus on social policy, economic growth and security challenges. It is unclear what about this is particularly novel given that they have been in government for the past four years. The SPD have attributed their many political failures over to the FDP’s intransigence as a coalition partner; it is unclear what they believe they will be able to enact given their much weaker position in a potential coalition with the CDU.

Economic policy: the SPD has been advocating for a reform of Germany’s controversial debt break policy, and intends to borrow to invest in infrastructure. They also intend to provide tax rebates to firms based on their investments into fixed capital. Reforming the debt break is possibly the one SPD promise made where they have probably genuinely been blocked by their coalition partners — specifically, the FDP.

Salaries & pensions: they want to keep pension levels stable in the long-term at 48%; they also want to mainstream the idea of company pensions as a means to supplement state pensions.They intend to raise the income threshold for the top tax rate from €68,480 to €93,000. Is this compatible with their desire for increased investment? It all depends on whether they succeed at reforming the debt brake. They defend an early retirement age, after 45 years of contributions.

Housing: the SPD want to extend the rent brake, while closing loopholes (such as on partially furnished housing). They also intend to pass a number of laws speeding up the construction of housing units. These are welcome policies, but the party have also been rather quiet on how speculation on housing influences the market. When it comes to the Deutsche Wohnen & Co. Enteignen campaign, for instance, the SPD — along with the CDU — have led efforts to prevent it from moving forward, despite the referendum’s popular success.

Transport & mobility: the SPD intend to implement a general speed limit of 130 km/hr on the Autobahn, expand infrastructure for electric mobility, and create incentives to promote the use of (particularly German) electric vehicles. They also claim an intention to invest in rail infrastructure and modernise Deutsche Bahn.

Health: the SPD want structural reforms to ensure a solidarity-based healthcare system, including the introduction of a solidarity-based public insurance system. Besides that, they want to drive digitalisation efforts and guarantee timely appointments.

Climate: the SPD, liberated from the shackles of the FDP, are particularly focused on expanding Germany’s electric vehicle sector and phasing out combustion engines — sticking to their earlier deadline of 2035 for this phase-out. They are opposed to nuclear energy.

Education: the SPD claims to want to invest in education, particularly adult education. Free lunches for children are also part of their programme.

Feminism: the SPD claim (once again) to want to abolish Germany’s controversial Section 218, thereby making abortion a legal right. They intend to legally improve state support for care work, by offering both leaves and allowances for family care.

People with disabilities: the SPD intend to create discounted public transport tickets for people with disabilities, as well as to pass laws encouraging private enterprise widen barrier-free access.

Migration: while the SPD intend to retain policies making it easier for (some) migrants to obtain German citizenship, they also want stricter border controls, and to accelerate deportations — particularly of people with refugee status, the most vulnerable migrants.

Military, foreign policy & EU: the SPD intend to continue to send weapons to Ukraine, although they oppose the delivery of long-range weaponry. They also want to continue sending weapons to Israel, despite Olaf Scholz having seen wide censure for facilitating the genocide in Gaza. The SPD intend to maintain Germany’s defence budget, at 2% of GDP. Their coalition recently approved a spending package for the German military worth over 20 billion euros.

FDP

The Freie Demokratische Partei (Free Democratic Party/FDP) are also known as the Liberal Party — in the economic sense and not the social one. Formed in 1948, the FDP have been a junior party of several coalition governments, including the recent Ampel-Koalition. The coalition fell apart when the Minister of Finance, the FDP’s Christian Lindner, insisted on maintaining Germany’s infamous Schuldenbremse (debt brake) — and on slashing public spending (particularly on climate initiatives) to cover the government’s spending plans. The FDP’s programme prioritises economic growth and a strong economy, strengthening the security authorities, limiting migration, and slimming down the state.

Economic policy: the FDP intend to transform the economy by radically cutting down bureaucracy, making energy more affordable, cutting taxes, reducing state intervention, encouraging free trade, and enabling the quicker recognition of foreign academic degrees. Critically, they intend to maintain the Schuldenbremse, thus constraining the state’s ability to borrow.

Salaries & pensions: the FDP defend equity-based savings in private pension planning and pension plans based on stock investments. They wish to move the top tax bracket to €96,600, reject any form of wealth tax. They support creating a more “flexible” (read: precarious) labour force, and reducing the right to strike in the public sector.

Housing: the FDP support accelerating the construction of housing, simplifying Nebenkosten (utilities) laws, and removing the Mietpreisbremse (rent brake). They are opposed to a rent cap, and want to encourage more home ownership. Debt for thee but not for me, clearly.

Transport & Mobility: the FDP’s strategy for mobility relies heavily on supporting automobile use — no ban on combustion engines, and cheaper driver’s licenses available from the age of 16. They also advocate for the removal of the aviation tax.

Health: the FDP want to maintain both public and private health insurance, and encourage more organ donations. They also want a parliamentary inquiry into the handling of the pandemic in Germany.

Climate: the FDP intend to abolish the European Green Deal, and want to replace the German goal of climate neutrality by 2045 with a European goal of climate neutrality by 2050.

Education: the FDP want a paradigm change in the education system, as well as a reform of what they call “education federalism”. They want better preschool education, which to them implies…national compulsory language tests for all preschool children. Other such “improvements” include mandatory visits to synagogues for school students, and more teaching about the history of both Israel, and of the DDR. Presumably, neither of these will feature particularly nuanced historiography.

Feminism: the FDP advocate for stronger rights for women, better compatibility between family life and work. They claim to want to fight against domestic abuse, and intend to legalise egg donations. They state in their programme that they want to make medication for abortions more available and reform Section 218 — yet, alongside CDU, they decided against allowing a vote in the Bundestag to reform the current abortion law.

People with disabilities: their only mention of disabilities is to draw more attention to their existence.

Migration: the FDP wants to limit migration, by “making it easier for people who live with us and share our values” and “[making] it harder for people who don’t have the right to stay and those who endanger our security”. They defend strengthening European borders by strengthening FRONTEX, pushing asylum applications to be made in third states, and deporting anyone “without migration rights”. They also intend to refuse migrant status to people deemed to be antisemitic, racist or xenophobic.

Military, foreign policy & EU: the FDP want to strengthen security authorities, and increase the use of AI in the justice system. They defend increasing military spending, giving the Bundeswehr the means to “effectively defend our country”, and attempting to make it the best-armed military in Europe. They defend the delivery of weapons to Israel, as part of the German Staatsräson. They are in favor of mainstreaming the widely-criticised IHRA definition of antisemitism, and of denying state money to people or organisations which do not accept Israel’s right to exist. They also want to reinforce bans on organisations like Samidoun. The FDP defend Ukraine joining both the EU and NATO, as well as expanding the EU to include Moldova and the Western Balkans. They also wish to end accession negotiations with Turkey. They want an EU-wide withdrawal from Russian energy.

Bündnis 90/Die Grünen

Die Grünen — the Green party — are a major part of the ruling coalition, alongside the FDP and the SDP, since 2021. Their programme priorities include a reform of the debt brake, renovation of German infrastructure, and climate protection. They have also released a short version of their programme in English.

Economic policy: the Greens are not very different to the SPD economically: they support reforming the debt break in order to invest in Germany’s decaying infrastructure. They particularly intend to focus on expanding renewable energy.

Salaries & pensions: the Greens want to increase the minimum wage to €15, and to introduce tax credits for people with low incomes, single parents and those who supplement their income with citizen’s allowance (this was a measure that was planned but not implemented by the Ampel-Koalition). They intend to keep the retirement age at 67.

Housing: the Greens want to create more living space by converting attics, or by adding floors to existing buildings. They also advocate for more protection for tenants, particularly in the cases of termination for personal use (Eigenbedarfe).

Transport & Mobility: the Greens intend to keep the Deutschlandticket priced at €49 per month. They want to increase e-mobility and introduce a speed limit of 130km/h on the Autobahn. They want to improve railway infrastructure and to make short-haul flights unnecessary.

Health: the Greens want more medical care centers under municipal ownership, and to increase health kiosks and health regions as a way to improve healthcare. They defend the creation of a citizen’s insurance scheme, including statutory and private insurance.

Climate: the Greens want no softening of the climate targets, relying on different instruments — such as market-based incentives like support for businesses and households, or regulatory law. They want the richest to contribute to offsetting the costs of the climate crisis. They oppose the weakening of the EU’s Green Deal, instead choosing to expand it.

Education: the Greens want to reform the educational system through the federal government’s Start Up Opportunities Programme and the Future Investment Programme for Education. They also want to prevent school dropouts with a national strategy.

Feminism: they want to remove abortion from the criminal code, and implement the EU’s requirements on pay transparency. They want to ensure that women’s shelters are funded, and they defend a gender equitable equality policy that “also addresses men and takes their concerns into account”.

People with disabilities: the Greens want to improve access to voluntary work for people with disabilities, and guarantee minimum wage and pension entitlements. They intend to make the education system more inclusive.

Migration: the Greens want to push through visa agreements and training partnerships with third and transit countries, while demanding that partner countries take back nationals who are not granted residency rights in Germany. They want to further develop FRONTEX “in accordance with the rule of law”. They want to shorten deadlines for residency permits.

Military, foreign policy & EU: the Greens are paradoxically quite militaristic, and want to invest “significantly more than 2%” of GDP into the defense budget. They are not in favour of conscription, but they have an interest in making voluntary military service “more attractive”. When it comes to the EU, they want to expand it and are in favour of the inclusion of Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia and the Western Balkans. The Greens defend a negotiated two-state solution based on the 1967 borders for Israel/Palestine; having said that, they defend arms sales to Israel, going as far as to justify Israel’s bombing of hospitals and schools, which they claim “lose their protected status” when used to shelter combatants. They want “diplomatic, financial, humanitarian and military support” for Ukraine, and to prevent Russia’s military advances through economic pressure. Internally, they want to strengthen the security authorities and invest in personnel and equipment.

CDU/CSU

The Christian Democratic Union (CDU) is one of the major West German parties, founded after World War II. The Christian Social Union (CSU) is their Bavarian sister party. CDU/CSU, also collectively referred to as the Union, have governed Germany for the majority of the post-war period. Their programme priorities are to stop migration, implement economic austerity, and increase funding for the military.

Economic policy: defined by austerity and neoliberalism, the Union have made clear that their intention is to hold on to the debt brake and widely slash taxes, while simultaneously increasing military spending. They intend to achieve this through social cuts and other ‘efficiency’ increases They plan on slashing unemployment insurance, increasing employers’ ability to overwork their staff, and undoing laws which seek to limit human rights abuses in the production of goods sold in Germany. They also wish to lower Germany’s corporate tax rates, and to provide tax cuts to landlords.

Salaries & pensions: the Union intend to keep the retirement age the way it is.

Housing: the Union want more privately-financed construction, cutting regulations on the constructions of new buildings.

Transport & Mobility: the Union want to reduce costs for car drivers, including by reducing CO2 costs, in order to protect the auto industry.

Health: the Union want to maintain current healthcare spending. They also want to provide tax cuts to Kitas (kindergartens), instead of increasing government support to them.

Climate: the Union’s bold climate plan is mehr Markt, weniger Stadt (more market, less state) — implying that the free market enable competition for the cheapest energy. They also want to reduce taxes on electricity, although it is unclear how this would help the environment. Finally, they want to reintroduce German nuclear power.

Education: the Union do not spend much time discussing education, except for some small points on further privatising universities.

Feminism: when the Union talk about women’s rights, they mostly discuss protecting them from “Islamists”. Otherwise, they plan on maintaining abortion’s status as a criminal offence, and had avoided a vote in the Bundestag to reform the current abortion law, shortly before these elections. They also want to undo the self-determination law, by which people can (more) easily change their name and gender. They frame this as “protecting kids”.

People with disabilities: N/A

Migration: the Union want to undo the recent citizenship reforms, making it harder for people who seek to get German citizenship, and making it impossible for them to keep another passport when they receive a German one. They also plan on making the recognition of Israel’s Existenzrecht part of the citizenship process. They plan on maintaining checks at German borders, increasing powers for FRONTEX, including giving them a vague “territorial authority” and “sovereign powers”. Those who are facing deportation orders would, under their policies, be held by the police until their deportation. The Union want to use third state holding centres for migrants, as Italy is attempting in Albania.

Military, foreign policy & EU: the Union follow the SPD in wanting to increase the number of soldiers, but they also plan to institute more public oaths and support for German soldiers. They also want to re-introduce mandatory years of community service, alongside a limited conscription. They want to undo the partial legalisation of cannabis, and the requirement for German police to wear identifying numbers. They want to increase the use of AI for German internal security.

For further analysis on their election platform, you can read our article “What are the CDU promising this election?” by Rowan Gaudet.

BSW

The Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht (Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance/BSW) was founded in 2024 by Wagenknecht herself, and some other former Linke members that decided to split from the party. They consider themselves to be on the left side when it comes to economic or some social issues, but are on the right when it comes to migration, gender diversity or climate policy. Their programme includes a reform of criminal justice, the opposition to a shift towards renewable energy, realisation of gender equality as prescribed in the constitutional rights (Grundgesetz) or disengagement in conflict except diplomatic peace efforts.

Economic policy: the BSW want a focus on strengthening domestic demand through higher wages and collective bargaining agreements, controlling mergers to prevent the expansion and emergence of mega corporations and limiting tax-free rights on real estate assets to buildings used by owners as private residences.

Salaries & pensions: the BSW defend a €15 minimum wage, tax-free pensions up to €2000/month, a minimum pension (after 40 years of payments to the social security) of €1500 per month. They want to raise the tax-free income limit (but don’t mention a value) as well as institute a 1% wealth tax on anything above €25 million.

Housing: the BSW intend to accelerate communal and social housing contracts through low-interest loans to companies undertaking such projects, defending of the introduction of a nation-wide rent cap and instituting 10-year rent freezes in all areas where rent prices are disproportionate to average income — as well as implementing more legislation to prevent rent gouging.

Transport & mobility: the BSW have the ultimate goal of transferring more traffic from highways and roads to rail. They intend to achieve this with low-cost bus and rail tickets and “free choice” transport, and the expansion of public networks and subsidized leases in areas where public transport is not viable. They wish to invest in alternative fuel and motor technology.

Health: the BSW are against the digitisation of health data. They want to replace the current system with universal healthcare, with the inclusion of necessary optometry and dental inclusion in the new system, and want to transfer pension benefits from private insurance companies into a public system. They intend to provide higher state funding for care homes, create more medical schools, and psychotherapy training spaces. They also want to invest less into attracting migrant doctors.

Climate: the BSW want to repeal the Verbrennerverbot (fuel-burning car ban), the heating law (requiring, among other points, new buildings to be heated with majority renewable energy), and carbon taxes. Despite this, they defend an increase in the state-farm cooperative biofuel plants and intend to adhere to the Paris Agreement. They want to use public funds rather than energy costs to private persons as the primary means of funding the expansion of green infrastructure.

Education: the BSW want free activities for children during school holidays, a “full day” schooling model including meals and free sport, music and art opportunities. They want to invest in primary and secondary certification for adult migrants.

Feminism: the BSW are in favor of fully legalising abortion up until 12 weeks and defending free contraceptives through prescriptions for those who need them. They want to make education on gender-based violence part of the school curriculum, and to repeal the SBGG (the gender self-identification law), enacting a name/gender marker change policy that requires medical testimony. They want sex offenders barred from changing their legal gender. They advocate for trans women to be excluded from womens’ sports.

People with disabilities: the BSW want a more consistent implementation of the UN Disability Rights Convention.

Migration: the BSW want to implement the Jobturbo policy, providing express pathways to employment for asylum seekers and refugees. They want to move to a preventative model that focuses on combating the reasons for migration in immigrants’ countries of origin. They claim that asylum law is being “abused on a large scale”, and, as a consequence, want to increase deportations for those without residence permits. They want to change existing laws (and, “if necessary”, the Constitution) in order to allow refugees to be deported following conflicts with the law. They want to withdraw Germany from the Global Compact for Migration.

Military, foreign policy & EU: the BSW want to restructure the military for defence, rather than for geopolitical interests. They demand an immediate ceasefire and two-state solution in Israel and Palestine, and an end to weapons deliveries to Ukraine. They want to make it impossible for private shareholders to receive armament profits. In terms of policing, they are in favour of increasing police presence in public spaces and modernising police equipment, and for increasing protections for emergency service personnel against “verbal attacks”. They want more visible police presence on streets and public spaces, and they want to repeal Section 188 of the Criminal Code, which prohibits defamation, insult and slander directed at public political figures.

On which note — for further analysis, you can refer to Vinit Ravishankar’s Anti-Wagenknecht, published on The Left Berlin.

In Conclusion

Considering the deeply undemocratic nature of the party, we have decided to leave the Alternative für Deutschland (Alternative for Germany/AfD) out of this explainer. There are multiple articles on TLB analysing and critiquing the far-right party, namely:

The Left Berlin has also compiled a dossier of relevant articles to this election.

Finally, if you have the right to vote, we urge you to do so — and to vote for the left. Monday will be yet another good day to fight.