This article originally appeared in The Red Phoenix on the 200th anniversary of Marx’s birth.

On the 200th anniversary of Karl Marx’s birth, many commemorations of this great man will be made. Even his bourgeois enemies will no doubt acknowledge how brilliant he was. However, these observers will also label him as a “wishful” and “flawed” thinker rather than as a scientist, and they will claim that history has proven him wrong.

Is that a correct assessment?

This is not a biography or a full evaluation. Several excellent biographies exist (for example Mehring F; ‘Karl Marx’; Ann Arbor 1973; or Gabriel M; ‘Love and Capital – Karl and Jenny Marx and the birth of a new revolution’; New York 2011). Moreover, complete critical evaluations have been done several times over. For example, we refer to a short, excellent, synopsis by Lenin (Lenin VI; ‘The Three Sources and Three Component Parts of Marxism’. Collected Works, Progress Publishers, 1977, Moscow, Volume 19, pages 21-28).

Instead, we intend to consider two serious charges laid by critics against Marx. The charges are both very relevant in the battles socialists face in the 21st century.

The first charge is that when Marx and Engels argued that technological change was a motor of history and ultimately would benefit society, they ignored humanity’s despoiling effect on the environment.

The second charge is that Marx and Engels were wrong to claim that workers living standards would fall and that workers stood to gain from fighting against capitalism.

We note that Marx was not a solitary genius – his life work was an alliance with that greatest of all partners – Frederick Engels. Hence, at times we will cite Engels as the two formed an intellectual and fighting partnership.

Marx’s life work was dedicated to the fight for socialism. But in forming his weapons, Marx had to master several areas of linked expertise. The questions we examine move from his earliest weapon – philosophy – to economics – and to questions of socialist strategy.

FIRST CHARGE:

Marx ignored how progress in technology and increase in the productive forces destroys the environment. Marx was “green” blind.

This charge boils down to the claim that Marx’s philosophical position on man’s relationship to nature is wrong, as gauged by the evident current crisis of climate change. This is leveled by both openly bourgeois ideologists and progressives. The latter includes some who are “green,” and some self-described Marxists. In addition, some Trotskyists recently agreed that Marx and Engels understood the environmental consequences of man’s labour. But these go on to argue that the Soviet state under J.V. Stalin subverted this understanding to cause environmental chaos. In the latter school must be counted Paul Burkett and John Bellamy Foster.

Our answers lie in the basic principles that Marx and Engels articulated as forming the core of dialectical and historical materialism. These principles became “the theoretical basis of Communism.” (Stalin J.V. for Commission of the CC of CPSU(B); History of the CPSU (B); Moscow 1939; p. 105). We will then, briefly, respond to the Trotskyite attack on the USSR.

Does Marx see environmental destruction – and if so – how did he think it arose? His answer can be summarised as follows.

Man is a part of nature and undeniably both affects nature, and, in turn, is himself affected by nature. (I will stay with the word “Man” – which was then universally used to mean humanity). This two-way relationship is a dialectical one. Moreover, in this relationship – from the dawn of society – man despoils nature. However, this despoliation becomes more intense and malignant under capitalism. There is only one way to overcome this, it is by “control” and “regulation.” But only a revolution in society can bring this about. Let us follow Marx in his reasoning in a little more detail.

Firstly, Marx saw man as a part of nature, but in a dialectical relationship. Such an interaction was expressed by Marx and Engels in The German Ideology:

“We know only one science, the science of history. History can be viewed from two sides: it can be divided into the history of nature and that of man. The two sides, however, are not to be seen as independent entities. As long as man has existed, nature and man have affected each other.”

Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, excerpt from The German Ideology, Selected Works, Volume 1: Moscow; 1969. p.17. [NB: This is a crossed-out passage in the manuscript]

In this, man remains a part of nature:

“In a physical sense, man lives only from these natural products, whether in the form of nourishment, heating, clothing, shelter, etc.… Man lives from nature – i.e., nature is his body – and he must maintain a continuing dialogue with it if he is not to die. To say that man’s physical and mental life is linked to nature simply means that nature is linked to itself, for man is a part of nature.”

“Marx K; ‘Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844”

Undoubtedly, man is “a part of nature,” yet separate in some way also. So how does man get “separated” from nature such that he is “affected” by nature and still an “alienated” part of it? Marx answers that producing for livelihood, or performing labour, is the demarcating point:

“Men can be distinguished from animals by consciousness, by religion or anything else you like. They themselves begin to distinguish themselves from animals, as soon as they begin to produce their means of subsistence, a step which is conditioned by their physical organisation. By producing their means of subsistence men are indirectly producing their actual material life.”

Ibid Volume 1; p. 20.

When someone starts their labour, Marx in his life’s work – Capital – wrote famously that they perform labour which engages in a two-way process. This “two-way-edness” is a dialectical process. In this he changes nature, but in doing so, is also “simultaneously chang(ing) his own nature”:

“Labour is, first of all, a process between man and nature, a process by which man, through his own actions, mediates, regulates and controls the metabolism between himself and nature. He confronts the materials of nature as a force of nature. He sets in motion the natural forces which belong to his own body, his arms, legs, head and hands, in order to appropriate the materials of nature in a form adapted to his own needs. Through this movement he acts upon external nature and changes it, and in this way, he simultaneously changes his own nature.”

(Marx, Capital, vol. 1, p. 283).

There are important implications of this relationship. Since this is a dialectical interplay, it must affect how man thinks and perceives reality. Does the world “exist” outside of man? Or is it only in his brain that the world “exists?” What is primary – is the mind primary and the external world a “projection” of man’s thought? To think in this way is to be an idealist. Alternatively, is the thought in the mind a reflection of nature? To think in this way is to be a materialist.

“The question of the relation of thinking to being, the relation of spirit to nature is the paramount question of the whole of philosophy… The answers which the philosophers gave to this question split them into two great camps. Those who asserted the primacy of spirit to nature. . . comprised the camp of idealism. The others, who regarded nature as primary, belonged to the various schools of materialism.”

Ibid; History of the CPSU (B): p. 112

Marx’s early intellectual life already revolved around the ancient materialists, in particular Epicurus of Greece. Following Epicurus, he confirmed his own materialism. Marx answers the question of the world’s existence, as a materialist. This means that the world truly exists:

“the material sensuously perceptible world to which we ourselves belong is the only reality.”

Ibid; p. 112.

So quickly Marx when examining work and labour, realised that the real world forms thoughts and ideology. Rather than the other way around – where thought forms the world.

But another profound consequence of this dialectical interaction between man and nature: man despoils nature – “cultivation – (if) not consciously controlled creates deserts.”

Marx wrote in a letter to Engels:

“Very interesting is the book by Fraas (1847): Klima und Pflanzenwelt in der Zeit, eine Geschichte beider [Climate and the Plant World throughout the Ages, a History of Both], namely as proving that climate and flora change in historical times. He is a Darwinist before Darwin; and admits even the species developing in historical times. But he is at the same time agronomist. He claims that with cultivation – depending on its degree – the “moisture” so beloved by the peasants gets lost (hence also the plants migrate from south to north), and finally steppe formation occurs. The first effect of cultivation is useful, but finally devastating through deforestation…

The conclusion is that cultivation – when it proceeds in natural growth and is not consciously controlled (as a bourgeois he naturally does not reach this point) – leaves deserts behind it, Persia, Mesopotamia, etc., Greece. So once again an unconscious socialist tendency!”

(Marx to Engels: Marx-Engels Correspondence 1868 Letter from Marx to Engels In Manchester 25 March, 1868; Gesamtausgabe, International Publishers, 1942; Selected Correspondence).

Marx describes the evolution of society from its earliest days through to capitalism. In doing this he traces the growth of the town. Its population rises as the peasant is “enclosed” and loses rights to common land. Yet as towns grow, the rhythm of the country life is destroyed. There, a natural recycling of wastes of life, including manure, enriches the growing soils. Now town wastes are simply turned into rivers as effluent and are not recycled into soil nutrients. This “disturbs the metabolic interaction between man and earth” with profound consequences:

“it prevents the return to the soil of its constituent elements consumed by man in the form of food and clothing; hence it hinders the operation of the eternal natural condition for the lasting fertility of the soil… all progress increasing the fertility of the soil for a given time is a progress towards ruining the more long-lasting sources of that fertility… capitalist production therefore, only develops the techniques and the degree of combination of the social process of production by simultaneously undermining the original sources of all wealth – the soil and the worker.”

(Marx, Capital, Volume 1, Penguin edition; London; 1976; p. 637-38).

And capital in its cease-less quest for more profit, destroys all before it:

“Capital creates the bourgeois society, and the universal appropriation of nature as well as of the social bond itself by the members of society….. For the first time, nature becomes purely an object for humankind, purely a matter of utility; ceases to be recognized as a power for itself; and the theoretical discovery of its autonomous laws appears merely as a ruse so as to subjugate it under human needs, whether as an object of consumption or as a means of production. In accord with this tendency, capital drives beyond national barriers…. It is destructive … and constantly revolutionizes it, tearing down all the barriers which hem in the development of the forces of production, the expansion of needs, the all-sided development of production, and the exploitation and exchange of natural and mental forces.”

(Marx, Grundrisse; Penguin edition; London; 1973), pp. 409–410.

And later Marx writes:

“[t]he development of culture and of industry in general has evinced itself in such energetic destruction of forest that everything done by it conversely for their preservation and restoration appears infinitesimal.”

Marx K, Capital Volume 2 (p.248)

But – we have already seen that Marx had proposed a solution. As he put it: “Cultivation – when it is not consciously controlled. . . leaves deserts behind” – indicating that a rational social control is the answer. This solution is more vividly and fully stated in “Labour in the transition from Ape to Man” by Engels. Engels restates the view that labour leads to ruin of ecological balance. He concludes that “regulation” will require a “revolution”:

“Let us not, however, flatter ourselves overmuch on account of our human victories over nature. For each such victory nature takes its revenge on us. Each victory, it is true, in the first place brings about the results we expected, but in the second and third places it has quite different, unforeseen effects which only too often cancel the first. The people who, in Mesopotamia, Greece, Asia Minor and elsewhere, destroyed the forests to obtain cultivable land, never dreamed that by removing along with the forests the collecting centers and reservoirs of moisture they were laying the basis for the present forlorn state of those countries. When the Italians of the Alps used up the pine forests on the southern slopes, so carefully cherished on the northern slopes, they had no inkling that by doing so they were cutting at the roots of the dairy industry in their region; they had still less inkling that they were thereby depriving their mountain springs of water for the greater part of the year, and making it possible for them to pour still more furious torrents on the plains during the rainy seasons. Those who spread the potato in Europe were not aware that with these farinaceous tubers they were at the same time spreading scrofula. Thus at every step we are reminded that we by no means rule over nature like a conqueror over a foreign people, like someone standing outside nature – but that we, with flesh, blood and brain, belong to nature, and exist in its midst, and that all our mastery of it consists in the fact that we have the advantage over all other creatures of being able to learn its laws and apply them correctly.

And, in fact, with every day that passes we are acquiring a better understanding of these laws and getting to perceive both the more immediate and the more remote consequences of our interference with the traditional course of nature. In particular, after the mighty advances made by the natural sciences in the present century, we are more than ever in a position to realize, and hence to control, also the more remote natural consequences of at least our day-to-day production activities. But the more this progresses the more will men not only feel but also know their oneness with nature….

It required the labour of thousands of years for us to learn a little of how to calculate the more remote natural effects of our actions in the field of production, but it has been still more difficult in regard to the more remote social effects of these actions. ….. we are gradually learning to get a clear view of the indirect, more remote social effects of our production activity, and so are afforded an opportunity to control and regulate these effects as well.

This regulation, however, requires something more than mere knowledge. It requires a complete revolution in our hitherto existing mode of production, and simultaneously a revolution in our whole contemporary social order.

Engels, Frederick. The Part played by Labour in the Transition from Ape to Marx; In ‘Selected Works Marx & Engels’; Moscow 1970; volume 3; pp. 78-79;

So important was this ecological principle of soil-regulation to them, that Marx and Engels in the Communist Manifesto of 1847, stated as part of their Ten-Point Plan for the working class – point 7:

“Nevertheless, in most advanced countries, the following will be pretty generally applicable.

- Abolition of property in land and application of all rents of land to public purposes.

- A heavy progressive or graduated income tax.

- Abolition of all rights of inheritance.

- Confiscation of the property of all emigrants and rebels.

- Centralization of credit in the hands of the state, by means of a national bank with State capital and an exclusive monopoly.

- Centralization of the means of communication and transport in the hands of the State.

- Extension of factories and instruments of production owned by the State; the bringing into cultivation of waste-lands, and the improvement of the soil generally in accordance with a common plan.

- Equal liability of all to work. Establishment of industrial armies, especially for agriculture.

- Combination of agriculture with manufacturing industries; gradual abolition of all the distinction between town and country by a more equable distribution of the populace over the country.

- Free education for all children in public schools. Abolition of children’s factory labour in its present form. Combination of education with industrial production, &c, &c”.

(“Marx and Engels; The Communist Manifesto, Chapter 2)

To conclude on the first charge: Marx was a profound environmentalist, and laid the foundation of a dialectical realist materialist philosophy. As he did so, he clearly depicted the relation of man to nature. The charge – that Marx was ignorant of the effects of technology on the environment – is false.

We believe it is helpful to here take a very short digression on an important application of Marx’s views on environment, as applied in the USSR.

Marx and Engels had pointed out that only a revolution could “control” or “regulate” the despoliation of nature. This revolution of course occurred in the 1917 Bolshevik revolution, which went on to form the USSR. And following that revolution, the reconciliation between man and nature took several turns – as the battle between communists and reactionaries continued over the years.

Trotskyist authors have recently placed an important emphasis upon Marx’s awareness of the environment. Their re-emphasis of this aspect of Marx has correctly rebutted the academicians disparaging Marx’s so-called “Prometheanism.” Leading proponents in this task, include for example, John Bellamy Foster, and Paul Burkett. Their works are important to reclaiming Marxist history. Yet they couple this progress with an ahistorical, factually incorrect, and regressive approach to the steps taken in the USSR. Hence, Foster claims that Stalin destroyed agriculture and the environment in the USSR. Such charges were examined in 1993, by Alliance-ML (see part 4).

The article argued that Stalin’s plan for agriculture, and for “Transformation of Nature” by planting was in fact progressive. It is important to note then, that subsequent work by independent bourgeois scholars of this topic, by and large confirm this conclusion:

“Environmentalism survived, and even thrived, in Stalin’s Soviet Union, establishing levels of protection unparalleled anywhere in the world, although for only one component of the Soviet environment: the immense forests of the Russian heartland. Throughout the early Soviet period, the agencies in charge of timber extraction repeatedly pressed for greater latitude, advancing visions of highly engineered, regularized woodlands while employing aggressive, revolutionary rhetoric. Yet with one quickly reversed exception, the Politburo consistently rejected the drive toward hyper-industrialism in the forest. After briefly capitulating to the industrialists’ unrelenting attacks on conservationism in 1929, Stalin’s government reversed course, and in the 1930s and 1940s set aside ever larger tracts of Russia’s most valuable forests as preserves, off-limits to industrial exploitation. Forest protection ultimately rose to such prominence during the last six years of Stalin’s rule that the Politburo took control of the Soviet forest away from the Ministry of Heavy Industry; and elevated the nation’s forest conservation bureau to the dominant position in implementing policy. …

Stalin-era environmentalism reached its zenith in 1947 with the creation of the Ministry of Forest Management (Minleskhoz). (Another initiative from this period related to forestry, the Great Stalin Plan for the Transformation of Nature of 1948-53, sought to reverse human-induced climate change via afforestation…) The period when Minleskhoz dominated Soviet forest management, however, was brief. On March 15,1953, six days after Stalin’s funeral, Minleskhoz was liquidated….. When Stalin passed from the scene, supporters of forest protection apparently lost the one political actor in Soviet history who was both willing to confront the industrial bureaus and powerful enough to tip the balance in conservation’s favor.”

(Brain, Stephen. Stalin’s Environmentalism. The Russian Review, Vol. 69, No. 1 (Jan., 2010), pp. 93-118)

Charge 2: Marx was wrong to claim that workers living standards would fall, and that their objective well-being laid in fighting against capitalism.

The question of “immiseration” of the working class was discussed by W. B. Bland in the last century. We first cite key parts of his work, which rebuts both Omerod, and before him Sir Karl Popper. (Bland W.B.; The Marxist-Leninist Research Bureau: New Series: No. 9; “Marx And The Theory Of The Absolute Impoverishment Of The Working Class Under Capitalism”).

This is a very recurrent critique of Marx – because it lies at the heart of the objective appeal of Marxism for the working class. Indeed, Bland put it this way:

“Perhaps the commonest economic ‘charge’ against Marx is that he argued that the working class would become impoverished to the point of immiseration. A prominent bourgeois attacker was Sir Karl Popper. But even revisionist CPGB theoreticians such as Maurice Cornforth argued for this.” (Bland, Ibid).

Even very recently, Paul Omerod (an economist at University College London and a partner at Volterra Partners consultancy), argues in the same vein, as follows:

“You see, Marx was completely wrong on a fundamental issue. Marx thought, correctly, that the build-up of capital and the advance of technology would create long term growth in the economy. However, he believed that the capitalist class would expropriate all the gains. Wages would remain close to subsistence levels – the ‘immiseration of the working class’ as he called it.”

Omerod argues next that workers have it easy under capitalism and their living standards have “boomed” since the 19th century:

“In fact, living standards have boomed for everyone in the West since the middle of the 19th century. Leisure hours have increased dramatically and, far from being sent up chimneys at the age of three, young people today do not enter the labour force until at least 18.

Marx made the very frequent forecasting mistake of simply extrapolating the trend of the recent past. In the early decades of the Industrial Revolution, just before he wrote, real wages were indeed held down, as the charts in Carney’s speech show. The benefits of growth accrued to those who owned the new machines. Marxists call this the phase of ‘primitive accumulation.’”

Bland had a dry sense of humour, consequently he starts his essay as follows:

“The Marxist theory of wages was, of course, not magically revealed to Marx as he sat in the shade of a banyan tree in the grounds of the British Museum.”

This reminds us that Marx put his life’s energy and blood and muscle into understanding the real mechanisms of society and capital. Bland first defines “absolute” impoverishment and “relative” impoverishment, in order to argue that Marx agreed there was a “relative” impoverishment of the working class. Then Bland agrees that Marx did argue that “real wages . . . never rise proportionally to the productive power of labour”:

“Marx had however never argued for ‘absolute’ impoverishment, rather he had argued that there would be a “relative impoverishment”:

‘Absolute impoverishment’ is defined in the Great Soviet Encyclopedia as:

”a tendency of lowering in the living standard of the proletariat.”

(‘Great Soviet Encyclopedia’, Volume 1; New York; 1973; p.33).

while “relative impoverishment” is defined in the Great Soviet Encyclopedia as:

” a tendency toward decreasing the working class’s share in the national income.”

(‘Great Soviet Encyclopedia’, Volume 1; New York; 1973; p.33).

There is no doubt that Karl Marx accepted the theory of the relative impoverishment of the working class under capitalism, for he says:

“Real wages . . . never rise proportionally to the productive power of labour,”

(Karl Marx: ‘Capital: A Critical Analysis of Capitalist Production’, Volume 1; Moscow; 1974; p. 566)”. (Bland Ibid).

It is true that initially Marx and Engels had adopted a theory largely drawn from Ricardo – that the wage level of workers would be at subsistence levels. However, in Marx’s mature economic work Capital, he had moved well away from a “subsistence wage” argument. Indeed, by June 1865, Marx had revised his theory on wages when he spoke to the General Council of the First International. Bland writes that by the time Capital was written in 1867, Marx had concluded that while labour-power was valued at the “means of subsistence” – there was also a “historical and moral element” that entered into the determination of the value of labour-power.

In the first volume of Marx’s Capital, published in September 1867, Marx repeated the basis of his amended law of wages:

“The value of labour-power is determined, as in the case of every other commodity, by the labour-time necessary for the production, and consequently also the reproduction, of this special article. . . . In other words, the value of labour-power is the value of the means of subsistence necessary for the maintenance of the labourer.”

(‘Karl Marx: ‘Capital: A Critical Analysis of Capitalist Production’, Volume 1; Moscow; 1974; p. 167).

However, Marx adds, a worker’s

” . . . natural wants, such as food, clothing, fuel and housing vary according to the climatic and other physical conditions of his country. On the other hand, the number and extent of his so-called necessary wants, as also the modes of satisfying them, are themselves the product of historical development, and depend therefore to a great extent on the degree of civilization of a country, more particularly on the conditions under which, and consequently on the habits and degree of comfort in which, the class of free labourers has been formed. In contradistinction therefore to the case of other commodities, there enters into the determination of the value of labour-power a historical and moral element.”

(Karl Marx: ibid., Volume 1; p. 168)”. Bland Ibid

The implication of this is that historically determined “necessary wants” change. And therefore, may well ensure that the value of labour power either rises or falls – along with the overall economy of the state.

As Bland says: “But the historical development of these ‘necessary wants’ continues, so that along with them the value of labour-power also increases. New inventions arise — such as the refrigerator, the car, television — and develop from luxuries for the rich into items which workers come to regard as necessaries. Marx himself speaks of a rise in the price of labour as a consequence of the accumulation of capital:

“A rise in the price of labour as a consequence of accumulation of capital only means, in fact, that the length and weight of the golden chain the wage-worker has already forged for himself allow of a relaxation in the tension of it”.

(Karl Marx: ibid., Volume 1; p. 579-80).

and of:

” . . . the worker’s participation in the higher even cultural satisfactions, . . newspaper subscriptions, attending lectures, educating his children, developing his taste, etc.”

(Karl Marx: ‘Grundrisse’ (Foundations); Harmondsworth; 1973; p. 287).

Marx indeed points out that one of the contradictions of capitalist society is that the capitalist has an interest in keeping low the income of his own employees in order to maximise his profits; but in contrast has an interest in not keeping low the income of the employees of other capitalists since these are (to him) merely consumers, part of his market. That is, he is interested in:

” . . . fobbing the worker off with ‘pious wishes’ . . . but only his own, because they stand towards him as workers; but by no means the remaining world of workers, for these stand towards him as consumers. In spite of all ‘pious’ speeches he therefore searches for means to spur them on to consumption, to give his wares new charms, to inspire them with new needs by constant chatter, etc.”

(Karl Marx: ibid; p. 287).

In periods of relatively full employment, in fact,

” . . . the workers . . . themselves act as consumers on a significant scale.”

(Karl Marx: ‘Theories of Surplus Value’, Part 3; Moscow; 1975; p. 223).

As Maurice Cornforth correctly points out:

“The very great advances in technology which accompany the accumulation of capital have the result that all kinds of amenities become available on a mass scale, and consequently the consumption of these becomes a part of the material requirements and expectations of the worker. In other words, with an advanced technology the worker comes to require for his maintenance various goods and services his forefathers did without.”

(Maurice Cornforth: op. cit.; p. 206-07).

Indeed, reputable economists agree that

” . . . Marx actually took for granted an increase in real wages in the course of capitalist development.”

(Karl Kuhne: op. cit., Volume 1; p. 227).

and that:

” . . . Marx never denies that real wages may rise under capitalism.”

(Mark Blaug: ‘Economic Theory in Retrospect’: Homewood (USA); 1962; p.243).

In addition, trade unionism — the application of the principle of monopoly power to the sale of labour power — enables organised workers to sell their labour power at a higher rate than they could under conditions of free competition between workers. As Engels wrote in May 1881:

“The law of wages . . . is not one which draws a hard and fast line. It is not inexorable within certain limits. There is at every time (great depression excepted) for every trade a certain latitude within which the rate of wages may be modified by the results of the struggle between the two contending parties.”

(Friedrich Engels: ‘The Wages System’, in: Karl Marx & Friedrich Engels: ‘Collected Works’, Volume 24; London; 1989; p. 380). Bland Ibid.

This also illustrates another point: It makes it clear that workers change their destiny by organising and fighting for their rights – even under capitalism – to some extent.

So Omerod and Popper are wrong about what exactly Marx was saying.

Nonetheless, what exactly has changed over recent times for workers?

Was Marx right about the trends of workers’ wages during capitalism?

Engels especially liked the phrase about the “proof of the pudding is in the eating.” How does the pudding taste?

Firstly: World-wide, the share of labour’s income as a percent of total income – has fallen between 1970-2014, according to the IMF. The IMF is not a worker-friendly organisation of course. See FIGURE 1 BELOW:

Secondly: After a period since 1955 of increasing wages, wages have plummeted in the UK since 1985. In a time series of data from the Bank of England, the Governor Mark Carney shows data that has a headline: “the first decade of real wages [fall] since the mid-19th Century”. (See Figure 2 below).

This also shows a time series plotting on the y-axis the output per worker (in other words productivity) against on the y-axis – the Real Wage – over the years 1770 to 1870. The gap represents the fact that wages do not equal the workers productivity, and hidden within this difference is the surplus value accruing to the capitalist.

So if the proportion that workers are taking home is going down, where is the rest going? I think we know… But anyway:

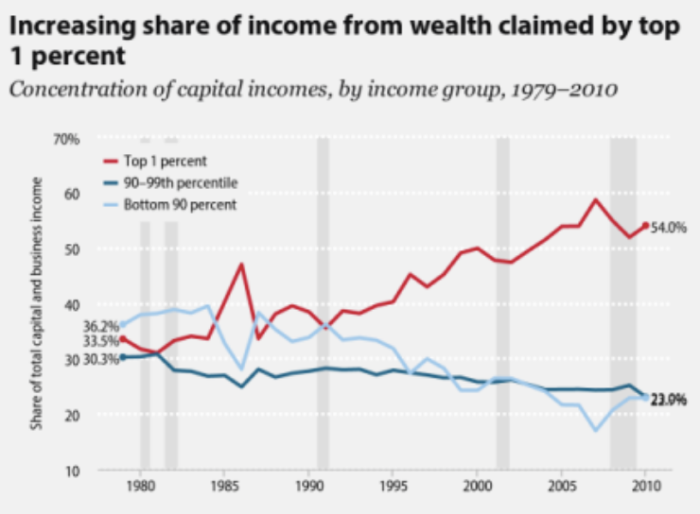

Thirdly: the amount of inequality in society has dramatically risen.

Below is shown the share of total income between 1980 and 2010 in the USA. The red line is the proportion for the top 1 percent earners and the light blue line is the bottom 90% earners.

Michael Roberts puts this into words as follows:

“The top 1 percent of earners in America now take home about 20 percent of the country’s pretax national income, compared with less than 12 percent in 1978, according to the research the economists published at the National Bureau of Economic Research. Over the same time in China, the top 1 percent doubled their share of income, rising from about 6 percent to 12 percent. America has experienced “a complete collapse of the bottom 50 percent income share in the U.S. between 1978 to 2015,” the authors wrote. “In contrast, and in spite of a similar qualitative trend, the bottom 50 percent share remains higher than the top 1 percent share in 2015 in China.”

(The Michael Roberts Blog: inequality after 150 years of Capital)

And below, FIGURE 5 shows data that inequality – as expressed by the Gini coefficient – is rising. On the y-axis is plotted the Gini and on the x-axis is depicted the Gross Domestic Product per capita (i.e. as a proportion of the amount of population) – of England Wales – over the period from the year 1270 to 2013. (The years are in blue on the curve). The Gini coefficient:

“the Gini coefficient (sometimes expressed as a Gini ratio or normalized Gini index) is a measure of statistical dispersion intended to represent the income or wealth distribution of a nation’s residents, and is the most commonly used measurement of inequality. It was developed by the Italian statistician and sociologist Corrado Gini .. in 1912… A Gini coefficient of zero expresses perfect equality, where all values are the same (for example, where everyone has the same income). A Gini coefficient of 1 (or 100%) expresses maximal inequality among values (e.g., for a large number of people, where only one person has all the income or consumption, and all others have none).”

(Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gini_coefficient)

In Michael Roberts’ words, this graph shows:

“According to the graph, (the year 1867) was the peak of inequality and it fell back over the next 100 years, thus appearing to refute Marx’s view that the working class would suffer ‘immiseration’ as capital took a growing share of value produced by labour. .. (but) in the 1960s…. most major capitalist economies began to generate an increase in inequality in both income and wealth – as the graph shows…The graph does reveal.. that inequality has been worsening in England to levels not seen since the 1920s.”

(The Michael Roberts Blog: Inequality after 150 years of Capital )

We must conclude that charge 2 against Marx must be rejected. Marx was correct that the wages of workers would remain below their productive output and that there would steadily be a reduced wage relative to the amount of the total societal income.

There is only one way out for the working class – to destroy the capitalist system.

CONCLUSION:

Marx continues to be defamed and painted as a naïf. But these and other charges against him, that attack him at the level of his science – are not valid. At the end we are left to mourn with Engels that upon his death:

“Mankind is shorter by a head, and the greatest head of our time at that. The proletarian movement goes on, but gone is its central figure”;

(Marx-Engels Correspondence 1883; Engels to Friedrich Adolph Sorge, in Hoboken; International Publishers (1968); Gestamtausgabe; at )

But as Engels ended:

“Well, we must see it through. What else are we here for? And we are not near losing courage yet.”

Ibid.

And we will finally close with, what capped Marx’s genius was the following insight – and what we, his heirs, try to internalise:

“The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point is to change it.”

Marx, “Thesis XI; “Theses On Feuerbach”; 1845, edited by Engels; Marx/Engels Selected Works, Volume One, p. 13 – 15