Questions: Phil Butland, Emily Baumgartner and Gregory Baumgartner

Hello, Ilan, thanks for speaking to us. Could you start by briefly introducing yourself?

My name is Ilan Pappe. I’m a professor at the University of Exeter in Britain, where I’m the director of the European Centre for Palestine studies. I’m also a historian, and a social and political activist.

The main reason we are talking today is that this year the 75th anniversary of the formation of the State of Israel. One of your books called the event, the Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine. Could you explain what you meant by this?

The ethnic cleansing of Palestine is actually the project of the settler colonial Zionist movement to take over the Palestinian homeland. At the right historical moment, from its perspective, it was able to take over much of the land and expel many of the native people from their land.

Before 1948, the Zionist movement did not have the power to implement such a massive expulsion of people. But once the British mandate was over, and they had built an adequate military capacity, they used the particular circumstances of the end of the British mandate to implement a huge operation of mass expulsion, or ethnic cleansing.

People were expelled in huge numbers because of who they were – Palestinians – not because of what they did. By the end of that operation, half of the Palestinian population became refugees. Half of their villages were demolished, and most of their towns were destroyed. In my understanding of the definition of ethnic cleansing, whether it’s a scholarly, legal, or moral definition, the planning, execution and ideology all justify describing the Israeli action in 1948 as ethnic cleansing.

In many ways, as I point out in the book, this has never ended, because the ethnic cleansing of 1948 was incomplete. And in many ways, it continues until this very day, if not on the same magnitude as the 1940s. But it still very much informs the Israeli actions against the Palestinians until today, wherever they are.

One of the tragedies for me about the Nakba is that the people who were doing the ethnic cleansing and creating refugees, were themselves refugees. People fleeing Nazi Germany, obviously didn’t want to stay in Germany, but they were also being largely denied access to the UK or the US. Did European Jews have any alternative to fleeing to Palestine?

The people who devised and oversaw the ethnic cleansing arrived in Palestine, much earlier – before the Holocaust. And when they arrived in Palestine in the 1920s, they still had options to go elsewhere.

It is absolutely true that since the rise of Nazism and fascism, Britain and the United States closed their doors, and quite a lot of the Jews who came from Central Europe and from areas that the Nazis occupied, had very few options. Palestine was one of the only places they could go to, but they were not the main force that decided on, and or perpetrated the ethnic cleansing. Most of the crimes committed in 1948 were committed by Zionists, many of whom, such as Yitzhak Rabin, Yigal Alon or Moshe Dayan, had been born in Palestine.

But definitely, one of the reasons that Jews came in large numbers in the 1930s to Palestine was that the West closed its gates for Jews who escaped from Europe. But I don’t think that most of the people who perpetrated this ethnic cleansing, were themselves victims of Nazi or fascist oppression.

Who were the people coming to Palestine? The Left was excited about communal Kibbutzim. After the Soviet Union was the first country to recognize Israel, many felt that there was something socialist about young Israel. How accurate was that belief?

The early Zionists were people came from Eastern Europe. And some of them were definitely inspired not only by the ideas of nationalism and colonialism, but also by the ideas of socialism and communism.

We know for example about the most important group that came to Palestine in the 1920s. This core group went on to grow the leadership of the Zionist community until the 1970s, and they were part of a more international socialist movement. Some of them even took part in the 1905 attempt to overthrow the Tsarist regime in Russia.

So yes, it was a fusion of three or four elements. One was socialism. The second was a nationalism which defined Judaism not as a religion but as a national identity. Thirdly, modernism. It was very important for them to build the idea of the modern Jew. No less important was colonialism – the idea that you are entitled to take any part of the world outside of Europe, regardless of who lives there.

But most of the Zionist settlers preferred not to live in socialist Kibbutzim, and therefore moved to the cities. By 1948, only a very small percentage of the Jewish settlers lived in those communes. But they were very powerful societies in terms of defining Zionist policies and strategy.

I think the most important thing was that they really believed–albeit wrongly–was that universal ideologies such as communism, and socialism, did not contradict settler colonialism. But of course, these two perspectives on life do not go together. One cannot be a socialist colonizer. Albert Memmi used to call it the Leftist Coloniser. And actually, you’re much worse in your criminal attitude because you are trying to use enlightened ideas to justify the actions on the ground.

How do you think they were able to square the circle? How could they justify to themselves this mixture of socialism and colonialism?

They still do it, it’s what we call the Zionist Left – which is not a force any more in Israeli politics, but used to be. This group squares not only socialism with colonialism, but also liberalism. The way you do it is by asking for exceptionalism. You say that in any other case, colonizing people, displacing them, and ethnically cleansing them is a crime. But in your case, there is a justification.

Whatever the justification is, you have to understand that there was no other way of doing it. At first, I am sure they found it difficult. But with inertia, and the educational system and indoctrination, they began to believe in it themselves.

No less important is the international reaction. Israelis might have felt differently, had the international socialist movement in Europe said to them: “wait a minute, that doesn’t work. In the age of decolonization, you cannot do what you’re doing”. Or if liberal Americans had said to them: “I’m sorry, but what you’re doing is against our moral values”.

However, they were lucky that the West decided that to accept this idea that you can have this exceptionalism when it comes to Israel and to Jews.

We are talking about a time when India and parts of Africa were being liberated. The Left stood firmly on the side of the anti-colonial movement. And yet–as you say–many of the same people turned a blind eye or even put Israel forward as a socialist paradigm. How did this happen?

In 1975, the United Nation finally had a huge membership of decolonized people. This was unlike the United Nations of 1947, which did not have one representative from the colonized world and legitimized the idea of a Jewish state in Palestine.

In 1975, the decolonized people were the majority in the United Nations. And one of the first things that they did was to pass a resolution which said, Zionism is racism. You cannot be a liberal or socialist Zionist. If you are a Zionist, then you’re not different from someone who supports apartheid in South Africa. That was the message of the United Nation resolution in 1975.

The big question was not what would African and Arab states do–instead focused on–how would the members of the United Nations coming from the West do vis-a-vis such an imposition? And, for whatever reason, Britain and France, and West Germany and later the EU, accepted the Israeli position. This position meant that you cannot treat Israel as a colonialist power, and therefore you cannot treat the Palestinian liberation movement as an anti-colonialist movement.

They accepted the Israeli framing of the Palestinian movement as a terrorist organization, and Israel as a democracy that defends itself. This changed the whole discourse about Israel and Palestine. And it extended the period in which the Left in Israel could think that it had found this amazing way of squaring the circle.

What is really interesting is what happened inside Israel. From 1977 onwards, the Israeli Jewish electorate says, “no, it doesn’t work. You really can’t be both democratic and Jewish”. And we see the result in the November 2022 election [which saw significant gains by the far right – editor’s note].

Israeli voters said: “no, you can either be a democratic state or the Jewish state. This whole idea that comes from Tel Aviv, or the Kibbutzim, that you can be both democratic and Jewish is nonsense.” Unfortunately for everyone concerned, their conclusion was “since we think that there are only two options, either you’re Jewish or democratic, we prefer to be Jewish one”.

That is, Jewish in the way that they understand Judaism, not the way I understand it. Their Jewish state is a theocratic, non-democratic, racist, apartheid state that needs all the power it has, because it still has a problem with the indigenous people of Palestine and those in the neighbourhood who support them.

This is something that leaders of the Left Zionist Movement never anticipated. They could not believe that their own electorate would say: “come on, it doesn’t work, stop, stop lying to yourself and to others. There’s nothing wrong in not being democratic. There’s nothing wrong with occupying someone else’s land and claiming it as yours. And there’s nothing wrong with using violent means in order to sustain your control.”

Do you think that the recent elections, and the new government, represent a qualitative shift in what’s happening in Israel?

It is a culmination of a qualitative shift that already started in 2000. There was a political force which was quite hegemonic in Israel until the late 1970s. They could come to the Social Democratic parties in Europe and say: “we are another social democratic country, no different from you”. And they were the hegemonic power in Israel until the 1970s.

But then the electorate said: “No, we don’t accept you”. Also, Arab Jews said that “because you are European Jews who are treating us in a very racist way, so we don’t want to be part of your version of a European country”. It seems that they are content with a more religious, traditional and racist state. This began in the late 1970s and took time to mature. Losing, or never winning, this Arab Jewish electorate (still 50% of the population) was the biggest failure of the Israeli Left.

From 2000 onwards, there was no social democratic power in Israel to talk about. There are parties who define themselves social democratic, but they don’t have any sizeable electorate behind them. And they have no influence in Israeli politics.

Since 2000, all the governments were either centre-right or right-right. If you look at the Knesset today, there are four members out 120, who define themselves as social democrats. There are more members who define themselves as Palestinian or anti-Zionist, but the vast majority define themselves as Zionists, and nationalist and religious. This is the face of Israel in 2022.

This is not an accident of history. It is an inevitable result of the whole idea of the settler colonial project.

One reaction to this lack of representation in parliament is the demonstrations in Israel which are barely precedented in terms of the size of mobilization against the government. At the same time, these demos clearly have nothing to say about the Palestinians. Do you think that they should be supported? And will they lead anywhere?

My Palestinian friends who are citizens of Israel discussed whether they should join the demonstrations. When consulted, my position was very clear. I said: “first of all, these demonstrators don’t want you there. They prefer not to see any Palestinian-Israeli citizen there. Secondly, the demonstrations are based on the idea that there is no connection between the occupation and the destruction of what is left of the Israeli democracy.”

This assumption of the demonstrators is totally wrong, of course. The two are connected and linked. The changes in the judicial system are meant to enable expansion of settlements and taking more severe actions against the Palestinian. This is the same package. It will take a bit longer for Israelis in Tel Aviv, and the high tech elite, who are worried about the way Israel is going, to see this. Hopefully they might see that there is a connection, but I’m not sure that they will. This is an internal Jewish debate that will have an impact on the Palestinians, but the Palestinians cannot impact that debate.

There is a misconception among some of the critics of Israel, that most of Israel’s money comes from the security services. That is not true. The most important income for Israel comes from high tech. Of course, some of that high tech is connected to security. But the high tech elite in Israel pays a sizeable percentage of the taxes and patriotically retains tens of billions of dollars in Israeli banks, as a statement of confidence in the Israeli economy. Since November 2022, they have begun to take the money out of Israel, and started to look for jobs outside of Israel.

This will undermine the Israeli economy very seriously, because it is a capitalist liberal economy which is based on such flow of money and human capital. It will be very interesting to see the impact on people who usually vote for the right wing, when their socio-economic conditions are affected.

The Israeli Central Bank has already increased interest rates eight times. This means that most Israelis who have mortgages are now paying three times more than they paid a few years ago. For many of them, three times more is half of their salary, and they have no chance of buying these houses.

So they will find it very difficult to pay their huge rent. And this government doesn’t have anyone there who has any capacity to deal with an economic crisis, which hasn’t happened yet, but will happen eventually.

How is the government justifying people having to pay these higher mortgages?

It is very difficult to answer this question logically. Today, the Knesset passed a law that allows Netanyahu to spend huge sums of money on renovating his house and his private aeroplane on the same day that people were told that their mortgage is being tripled. The people whose mortgages are being tripled, are generally people who vote for Netanyahu.

The people who don’t vote for Netanyahu are very well off. This change in the economy doesn’t bother them. But there is a certain psychology here which is not that easy to explain, and is not unique to Israel. Why do the electorate that suffer most from the economic and social policies of the government, continue to support the government?

So far one of the reasons that this occurs in Israel, is due to the government’s ability to tell its supporters that this is the necessary sacrifice for keeping the tribe and the nation together. This togetherness is necessary because we’re facing enemies from within and from without. That’s why they have to blow the Iranian danger out of proportion in order to cement support and divert attention from the socio-economic problems of the society.

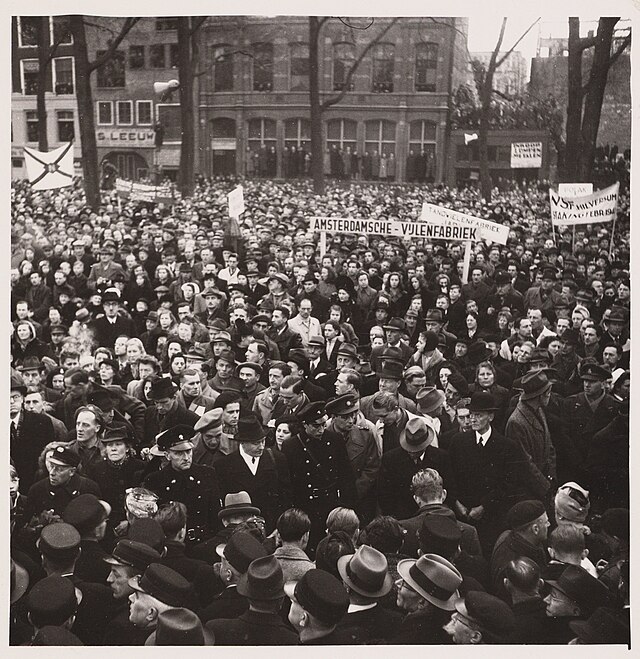

So far, it has worked. Every time that they are overdoing these oppressive economic measures, we say to ourselves, okay, now it will burst out. We thought it burst out in 2011, with the social protest movement of half a million people demonstrating in Tel Aviv against the government’s policies on education and housing.

It was mesmerising to see how it petered out. A year later in 2012, Israel went to war in Gaza in order to make sure that the demonstrators will go to the army and go to the war and forget about the social protest. The government has no economic solution for the current crisis. It will try to find a way of diverting the attention–whether it’s a war or a crisis–it is hard to predict, but it is very worrying.

If you talk to the younger generation, they were educated in a particularly indoctrinated educational system. It is very difficult to change their perspective. And Israel de-Arabized many of the Arab Jews (the Mizrahim), giving them the sense that being not Arab is the ticket to be part of the new Israel, and something which will help to distinguish them from the “Arabs” of Israel, who were depicted as lesser persons or human beings, and therefore made them second-rate citizens. There is so much work to be done there, for anyone carving for a change from within Israel.

Some things are logical. We understand why some of the North African Jews moved to the settlements from the poor neighbourhoods of Jerusalem. That was understandable. They lived in a slum, and were offered a villa in the West Bank. So they went with the government’s support. The settlements for the Arab Jews in Jerusalem were built near Jerusalem, not inside the West Bank.

But nowadays, I’m not sure how far the Israeli government can go with this. They have no economic solution to the gap between those who have and those who haven’t. This is a situation that they themselves created. And frankly, they don’t even have the wizards of the liberal economy any more.

What you’re saying, indirectly at least, means that Israeli high tech workers and Palestinians have got a common enemy in Israeli capital. Does that mean that there’s a possibility of them coming together against the same enemy?

Not in the near future, because unfortunately, these high tech people are also indoctrinated by the racist Zionist view that the Palestinians are non-Europeans, and not equal partners. But it may shift. I don’t want to sound overly optimistic. but people who work in the Israeli medical system know that 50% of the physicians in Israel are Palestinians, and that many of the heads of the departments in hospitals are Palestinians. Maybe it will help to re-humanize the Palestinians in the eyes of the Ashkenazi elite of Israel. But we have to wait and see, as it has not happened yet.

The real hope for change lies elsewhere. There is a need, which now seems utopian, for an alliance between the Jews who came from Arab and Muslim countries and the Palestinians all over historical Palestine. I know this is not going to happen very soon, and I’m not sure if it’s going to happen at all. But I would invest most of my efforts there.

How can the Palestinians avoid taking the same path as South Africa? As a supporter of the Initiative for the One Democratic State, how would a single democratic state under capitalist conditions avoid just continuing the old power relationships in a different way?

The Initiative is trying to find bridges between the Left and some of the political forces that emerged in Palestine after the 1970s, including the political Islamic forces. We see that there is a lot of common ground, not only to liberate a place from colonization, but to build a new one, which is based on egalitarian social and economic policies.

What we don’t want, is the compromise that Mandela made in South Africa. In order to see the end of apartheid, Mandela was willing to allow the capitalist interests in South Africa to remain powerful in a way that did not solve the most fundamental problems of South African society and economy. It’s better than having apartheid, but it creates new issues.

The way to avoid this post-apartheid reality is to make sure that while you discuss the means for decolonization, you also develop a social and economic post-colonial vision. Applying the means used to decolonize, you might be able to build a more just society. Namely, just not only in terms of the of the relationship between Jews and Palestinians–which is the main aim–but also between classes, between the rural areas within the periphery and the centre, and so on.

It really behoves the Palestinian Left to redefine its identity and goals, and to openly and critically look at the mistakes it made in the 1970s. This is where this energy can come from. On the Left we believe in intellectual, organic intellectuals, and profoundly looking at the problems and finding solutions. But we also need to be in contact with movements and receive the support of the people themselves.

Who do you think has the agency to enforce change? I agree with you that the Palestinian Left needs a better vision. But Palestinians are largely excluded from the Israeli economy and merely going on demonstrations mean you run the risk of being shot by Israeli soldiers. What will it take to change the balance of power?

A lot of people know what needs to be done. But we all are very bad in knowing how to do this. We need to take into account that Palestinian society is the youngest in the world. 50% of the Palestinians are under 18. And this younger generation has some clear ideas of who they are and where they want to go.

Unlike the politics from above, whether inside Israel or in the Palestinian occupied territories where people are divided ideologically and politically, the younger generation is far more unified in its analysis of the reality and its vision for the future. These energies need to find their way into the structures of representation and leadership that can move all of us in the right direction.

We experienced this both in the West in 2008, and during the so called Arab Spring in 2011-2. People were very hesitant to put their energies into organizational issues. They felt that organization creates bureaucracies, and bureaucracies tame down the energy and become corrupt. This is what they see around them in the Arab world, and also in the West.

So there needs to be a fusion of the revolutionary energies that are there. I think the Left always realized that you need organization and representation. You may be influenced by anarchism, but it doesn’t always work as a transformative force on the ground. We can agree that knowing exactly how to transform things is not easy.

One of the most interesting initiatives, which I hope it will include the Palestinians in Israel, is either to re-organize the PLO, or to find a substitute. It is necessary for all of us to have a more accepted representative, democratic Palestinian leadership that will push us all in the right direction. This is easier said than done, of course.

How could a new State be forged, ideally with economic relations which are divorced from the last century of Zionist war-making? How would it function economically, if there’s no war to constantly generate profits?

That goes together with the whole decolonization process. First of all, you dismantle the racist colonialist institutions. These institutions are based in capitalism. The main problem is not so much the militarized high tech, but the question of decolonization.

The energy that would be needed would be in such a different direction to security, that I don’t think you have to worry about it too much. Because either people will go along with this, or they won’t. And if they do, the high tech community would also have to contribute its share for building a post-colonial state and prioritise for instance, projects of absorbing the Palestinian refugees (since the implementation of the right of return would be crucial for a just solution) and be part of the effort for redistributing land and property and working out a credible mechanism of compensation.

The entry point is really the dismantling of colonialist institutions. These institutions are now so closely connected to the capitalist system, that the very dismantling or weakening of them may also begin with changes to the economic nature of the state.

The 2011 protest movements in Israel showed both the potential and limitations. The movement was huge, but it fell apart as soon as anyone mentioned Palestine. It happened at roughly the same time as the Arab Spring, but there seemed to be zero connections made with what was happening in North Africa. Was this inevitable?

Let me put it this way. In order to change the reality on the ground, our greatest hopes are not for change from within the Israeli society. If someone wants to see a change in Palestine, it would not come from within the Jewish society, but from the ability of the Palestinians to be more unified, and for the Muslim and Arab world to stand behind them.

People or governments in the West standing behind the Palestinian Liberation cause can bring a change. But anyone that waits for change from within Israel as an important component in transforming the situation–will, unfortunately, be disappointed.

Having said this, things are more dialectical. If we see all these things that I talked about–a change in the Muslim world, and in the way that Western governments are acting–this can have an influence on the ability of Israelis to be more assertive and maybe contribute to the change.

I would be very surprised if the current movement will do this. It’s an impressive movement. 100,000 people surrounding the Israeli Knesset on Monday is a show of force. But these people will make sure that the Palestine issue is not connected to their agenda. They will make sure that Palestinian Israelis are not part of this protest movement. And that’s why they will fail.

Maybe one day they will realize that if you want to change the Israeli political system from within, it needs to be done through Arab-Jewish cooperation. You cannot do it without the Palestinians in Israel. But Israel has grown up to be such a racist society, that for the vast majority of Jews, this is an unthinkable scenario.

Who should socialists in Germany and elsewhere be making links with? You don’t see much hope in Israel, and Fatah and Hamas are falling apart with corruption. Who are our partners in the region?

There is a thriving civil society which needs the support from people from the outside. It is very well organized in the West Bank. Even under the Hamas in Gaza, it has enough freedom to act. The same is true about the Palestinian society inside Israel.

And there is a positive development. Jews are no longer creating their own civil societies. They understand the limitation of the power. So if you are an anti-Zionist Jew, you are now joining a Palestinian NGO instead of creating your own. Some of the Palestinian national movements inside Israel used to say: “let the Jews develop their own critical mass and we will develop ours.” Now there is an understanding that it has to go together.

You can see it in Balad, the most important national party inside Israel. Although it never prohibited Israeli Jewish citizens from joining now they’re actively recruiting Israeli Jews, both for the party and also through a network of civil society organizations that is connected with the party.

There is also a call from 150 Palestinian NGOs inside Israel and the occupied territories for the Boycott, Divestment and Sanction campaign, It is a very important call, and something that socialist and progressive forces in Europe are ready contribute towards. I know how difficult it is in Germany, because of the legislation and the declaration in the Bundestag. But nonetheless, that should not deter us.

There is also an interesting new initiative. The PLO has started international anti-Israel apartheid committees everywhere in the world. This can form a new energy for the BDS movement or enhance the BDS movement even further. I think these initiatives are very important. You cannot rest. They need to be maintained.

One last question. You will be speaking in Berlin again in May at the Marxismuss conference. The subject is 75 years Nakba, but it’s also an opportunity to addressing some of the problems that we have in Germany. Our problem is not just the Bundestag resolution, but a self-censorship and lack of self confidence amongst the German Left regarding Palestine. How important you think is it to talk raise the issue of Palestine with a German audience?

Very, very important. Germany plays a very important role in this whole question. Germany’s justified guilt is manipulated in order to immunise Israel. Germany is an extremely critical political force in Europe. But it does not dare to take any bold actions as a political system, that would benefit the Palestinians and alleviate their suffering under Israeli oppression.

It’s very important to find a way of convincing the German public that they should not be intimidated. I come from a German Jewish family. I know very well what happened in Germany. We should not be intimidated by that particular chapter in history. On the contrary, that chapter means the Germans should be even more sensitive to the suffering of the Palestinians.

Germany should not deny the past, but instead say that this past requires a moral position on Palestine, not just on Israel. The Palestinians are a link in the victimisation chain that began in 1933. People in Germany who produce knowledge about Palestine–academics, journalists pundits, and definitely politicians–cannot act like they are part of the Israeli propaganda.

I know they are intelligent scholars, journalists, and politicians. It really breaks my heart to see them saying things that they know are not correct. The only reason they’re saying it is because of political, academic, or journalistic utility. They don’t want to be condemned as antisemites. This is more important in Germany than in any other country.

We have a great assignment of convincing them that, supporting the Palestinians is being anti-racist and anti-colonialist, and therefore cannot be an antisemitic act based on the mistaken belief that antisemitism is racism. This is easier said than done. But I think that academics should play a very important role here–in being accurate, in being accurate professional, in not abusing what they do as academics.

Germany always respected its academics, journalists, writers, intellectuals–but when it comes to Palestine, they behave like people with no backbone avoiding the desire to seek out the truth. And this is something that I think they should contemplate. Hopefully we can help them in this process.

We’re nearly out of time. Is there anything you’d like to say before we finish?

We should not give up on Germany. I’m beginning to give up on on the chances of changing Israeli society, but I’m not giving up on the younger German generation. We should still look at Germany as a place where there are processes that have not yet matured. And Germany’s is building itself all the time.