In the UK, a White Paper is the way government presents policy preferences before it introduces legislation. It is also a way of testing public opinion on controversial policy issues. The recent White Paper ‘Integration and innovation: working together to improve health and social care for all’ was heavily leaked. Headlines suggested that a significant change in government policy was in the offing with respect to reducing privatisation of NHS services – Keep Our NHS Public (KONP) argued that the opposite was in fact the case.

In his speech to parliament introducing the White Paper, Secretary of State for Health, Matt Hancock, declared:

“it takes the lessons we’ve learned in this pandemic of how the system can rise to meet huge challenges – and frames a legislative basis to support that effort. The pandemic has made the changes in this white paper more, not less, urgent”.

In other words, the major reforms to be introduced while the NHS is still reeling from the largest crisis in its existence are justified by recent experience of failing to prevent the highest death rate in the world. In contrast, while accepting the need for a public inquiry into management of the pandemic, the government asserts that it would be wrong to divert resources from the fight against Covid-19 at this time and an investigation will only take place once coronavirus has been vanquished.

We should remember that those who are now rushing to abolish the “disastrous” 2011 Health and Social Care Bill and replace it with new legislation are by and large those who enthusiastically supported the so-called Lansley act, turning a deaf ear to the many criticisms levelled by campaigners and health professionals alike. If this is not cause enough for concern with regard to the new White Paper, there are other throw away remarks that suggest the public are about to be duped once again.

Take, for example Hancock’s drawing attention to the portrait on his office wall:

“of Sir Henry Willink, who published the white paper in 1944, from this despatch box, that set out plans for “A National Health Service” that was later implemented by post-war governments.”

Hancock’s predecessor, Jeremy Hunt, also shared this particular version of history. Of course at the time, when Willink had been succeeded by Nye Bevan as minister of health, Conservative party MPs voted against Bevan’s NHS Bill, later bemoaning the fact the 1946 NHS Act had so comprehensively abandoned Willink’s proposals!

False statements and empty premises

An equally tenuous grasp of more recent history is demonstrated in the executive summary of the 2021 White Paper where the extraordinary claim is made that during the pandemic:

“NHS capacity grew; new hospitals were built in a matter of days.”

Presumably this is a reference to the white elephant vanity projects known as Nightingale Hospitals costing £530m, that were built but never filled with Covid-19 patients not least because they had no staff. Former health secretary Jeremy Hunt has been much less sanguine than Hancock in relation to pandemic measures, and has admitted responsibility for the neglect of manpower planning. In a recent interview on how the NHS was managing and the chronic understaffing, he commented:

“that doesn’t mean that the NHS does have the capacity it needs, and [that’s why] I concluded during my time as health secretary that we need many more doctors [and] nurses.”

NHS capacity was adequate for patients with Covid-19 only because interventions including cancellation of elective surgery, use of private hospitals, redeployment of existing staff and deployment of former and newly qualified medical staff were hurriedly made. This has had a disastrous impact on non-Covid related conditions with numbers waiting for elective procedures for over a year at its highest since 2008 – a more than hundredfold increase.

Marketing marketisation: the mis-selling of reforms as anti-privatisation

News headlines on the leaking of the White Paper often focused on how the proposals represented significant distancing from the private sector, leading some to think the government had undergone a fundamental change of heart. Others went even further and declared the imminent demise of the internal market/purchaser-provider split (a fundamental feature of the marketisation of health care) even though Hancock made it clear this was definitely not the case:

“Our proposals preserve the division between funding decisions and provision of care, which has been the cornerstone of efforts to ensure the best value for taxpayers for over 30 years”.

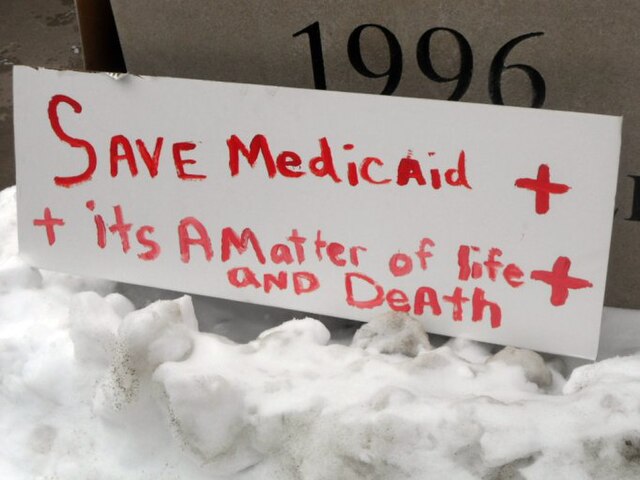

The public mistrust privatisation and in a poll last year 76% wanted to see the NHS “reinstated as a fully public service” against just 15% who wanted to see continued involvement of private companies. People have seen privatisation accelerated during the pandemic, and in the absence of any transparency. Deloitte, KPMG, Serco, Sodexo, Mitie, Boots and the US data mining group Palantir have secured taxpayer-funded contracts to manage Covid-19 drive-in testing centres, the purchasing of personal protective equipment (PPE) and the building of the Nightingale hospitals. The expensive failures to deliver were often obvious for all to see, and stood in stark contrast to the impressive vaccination programme that has relied on the energy and ingenuity of local community NHS teams – success behind which ministers now hide.

The government routinely denies incremental privatisation in the NHS, knowing it is unpopular with voters. In 2019 an extra £415m spent on private providers represented a 5% increase at the same time as Hancock was pledging there will be ‘no privatisation on my watch’. NHS England also obscures the true amount of spending on the independent sector, claiming 7% of budget rather than a more accurate 18% (excluding general practice). In addition, requests for more clarity through Freedom of Information requests are brushed aside and policy development goes on in secret. Hancock now considers that even discussing what should be publicly delivered and what delivered by the private sector is superfluous by common consent. In reality, the White Paper proposals do not push private companies away, but rather consolidate the market paradigm that the 2012 act strengthened and which the government has favoured during the Covid-19 pandemic. The covert takeover of general practices covering a third of a million Londoners by US corporate Centene last week is a grim illustration of what is to come.

Why the White Paper most certainly does not spell the end of privatisation

The proposed reforms have been critically reviewed. There can be no doubt they do not represent a sea change in government thinking with regard to the market in health care. As KONP pointed out when the White Paper was leaked:

“The Government could end private contracts today without legislation – and could have done at any point since 2013 – by scrapping the regulations that were added to Section 75 of the Health and Social Care Act. Instead this Government is ready to vastly increase privatisation in the NHS. Nothing in the leaked draft suggests bringing existing contracted-out services back in-house. Unless outsourcing is ended, much of the fragmentation created by the 2012 Act remains as an impediment to genuinely integrated care.”

Further clear indication in the White Paper proposals for potentially increasing the role of the private sector include:

- voluntary and independent sector providers will continue to have an important role

- new laboratory networks are being set up outside the NHS

- £10 billion is due to be spent on private hospitals to clear NHS waiting lists over the next 4 years (transferred from NHS funds)

- there are no plans to bring existing contracted-out services back in-house

- Integrated Care System (ICS) bodies as commissioners and NHS and Foundation trusts can opt to put more services out to tender if they wish

- a new ‘Health Systems Support Framework’ has been established to fast-track contracting out, with a pre-approved list of over 80 providers, almost all of them private sector and more than a quarter of them American companies (a significant expansion of private sector involvement in the NHS)

- there are no changes in the rules on procurement of non-clinical services, notably “professional services” such as consultancy and digital systems, which are central to the new ICS (and largely provided by the private sector)

- voluntary and private sector “partners” could be included in new ICS Health and Care Partnership Boards, shaping policies and services in each area: this would be another extension of private sector influence

- NHS Boards will be able to delegate some of their powers to providers or groups of providers; this could include private companies and is likely to reduce public accountability and transparency

- the changes pave the way for longer contracts such as the 10-15 yr contracts referred to in the accountable care organisation’s literature

- the end of the fixed tariff payment system for clinical services could allow private hospitals to under-cut NHS trusts, and cherry pick low cost simple elective cases, leaving the NHS saddled with more complex cases

The coronavirus pandemic – what are the lessons that should be learnt for health and care services?

The White Paper demonstrates that government has learnt the wrong lessons from the pandemic to inform planning of health service reform, and that social care has been largely left out of the equation. As others have concluded, Hancock has almost certainly grossly overestimated any potential benefits of his plans while underestimating the disruption they will cause, as well as misleading the public over their true nature. A full public inquiry into the handling of the pandemic could have provided important insight into reform that would repair the NHS, address the problems of social care, and provide a resilient health and care service for the future. Our People’s Covid Inquiry will rise to this challenge while we continue to campaign for a reinstated NHS free of the market.

This article was written for Keep Our NHS Public. Reproduced with permission