Very few institutions have been legitimised as extensively today as that of the nation-state. The hyphenated term in itself alludes to a troubled history: the unification of a nation — i.e. a people, with some “collective consciousness” — with a state — a formal bureaucracy with complete hegemony and sovereignty over a geographic location.

Nation-states are a very recent phenomenon. This is uncontroversial amongst both Marxist and liberal historiography. A key point of disagreement surrounds why they emerged. Liberals tend to associate the phenomenon with industrialisation and urbanisation, Gellner, for instance. He saw nation-states as essential to industrial society, with creation of a dominant standardised language and a state bureaucracy. Marxists on the other hand, tend to see nation-states arising as a consequence of the emergence of capitalist economic relations. Anderson famously focuses on the spread of print capitalism, and replacing sacred languages by local vernaculars as a key factor developing a national consciousness. Davidson discusses the utility of nationalism as a form of “psychic compensation” under capitalist alienation, easing class domination by mobilising working classes for “their” capitalists.

Today, given the dominance of the capitalist mode of production, the nation-state (i.e., the state) is universal. The entire world is divided into nation-states. Even if some are not seen as legitimate, the notion is universally seen as an appropriately “modern” way to organise the world. What is not universal, however, is the form of the nation-state. Japan, the United States of America, and Pakistan are all very different internal descriptions of nation. Yet each is as legitimate in the “international community” as the others. All have very similar outward-facing institutions — a bevy of diplomats, a government, a seat at the UN, etc.

Briefly, the nation-states in Europe emerged as follows. The origins lay in the birth of capitalism in modern England. The slow creation of the identity of an Englishman occurred over centuries, through the rise of the robust internal trade networks and the state capacity enabled by primitive accumulation. English, the language of the nascent bourgeoisie, began to dominate as Latin began to disappear. The ruling class became more attentive to the interests of burgeoning mercantile hubs. Land enclosures followed and with the growth of industry, spurred on mass migration to the cities.

Increasingly, the village community faded and the eternal feudal order that governed it began to give way to modernity. Peasants now found themselves doubly free (to sell their labour, free of their means of reproduction), but needed to be assimilated into being good Englishmen and women. Thus, early capitalist modernity led to the emergence of a very specific form of nation-state. It was characterised by constructing a mass culture, built on a unitary language and a unitary notion of “the people”. People had a shared history, and shared myths and collective imaginings.

France, driven by competition with Britain, set about rapidly restructuring the French state. The strongly centralised, homogeneous, indivisible republic that followed became a template for the rest of the world. The world became organised into linguistic nation-states. Many ethnic groups with their petty bourgeoisie began to demand their own formal language and state. Often, these deliberately-constructed nations came into existence after their respective states did. The Sardinian premier Massimo d’Azeglio said “L’Italia è fatta; restano da fare gli italiani” (We have created Italy; now we must create Italians). This gained impetus outside Western Europe after the First World War. Both Lenin and Woodrow Wilson championed the “right of people to self-determination”, specifically, their right to self-determination within the parameters of a state. Western European notions of culturally and linguistically homogenous nation-states became hegemonic, and seen as an essential transformation for a people to become a truly modern people.

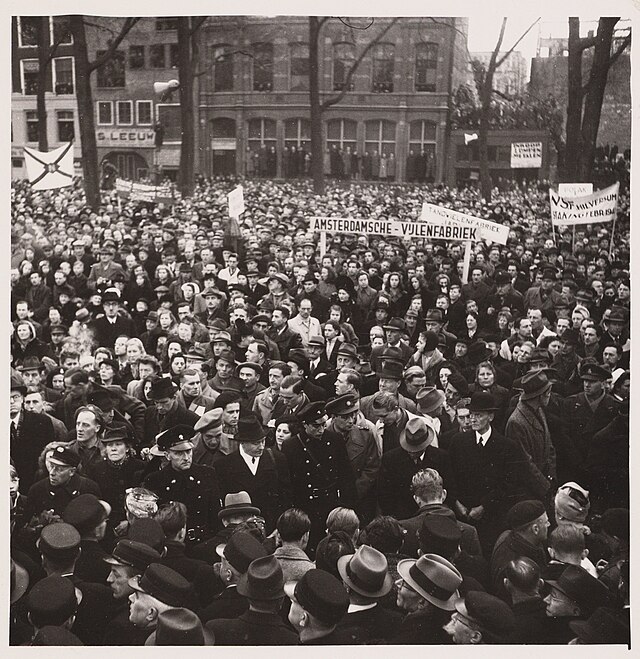

Unfortunately, latecomers to capitalist modernity were forced down a different path. The gradual homogenisation that had occurred in the north-west of Europe simply could not exist everywhere. The late Ottoman Empire, particularly Istanbul, was extremely heterogenous. As was Austria-Hungary where a 1911 census revealed that only 24% of the empire used German in their everyday lives. Emergent nationalism in most of Europe followed a very different trajectory to Britain or France. Attempts to resolve these contradictions, and to emulate their predecessors resulted in nationalist violence, reshaping the entire continent. Emergent nations, faced with a wide variety of ethnicities within their borders, found themselves facing the “minority problem”. Ethnic minorities found themselves facing mass deportations and ethnic cleansings all over the continent, in the wake of collapsing empires.

This was by no means a “natural” reordering of society, nor was it chance mob violence that spiralled out of control. All over Europe and the European periphery, these projects were legitimised and put into place top-down. They were expressions of state power. Ultimately, the Armenian genocide was not the doing of unruly mobs, but of the the nascent Turkish state. New nationalist thinking legitimised these movements. For example the Ottoman sociologist Ziya Gökalp’s views on Turkish nationhood as an “involuntary” linguistic and social solidarity. The universal hegemony of these proto-fascist tendencies, was encouraged by American “pragmatic” Wilsonianism. It wound up leading to varities of militant nationalism all over the region. Ethnic cleansings and pogroms grew to be seen as regrettable, yet absolutely inevitable.

Unfortunately, today, while the heart of ethnonationalism is once more at tenuous peace, the idea itself is far from dead, it has simply taken on different forms. Ethnonationalism has been transformed into the more politically correct “common sense” idea that all “functional” nations must be an ethnoculturally cohesive unit. If it weren’t for the pesky metropolitan elites, the idea goes, England would remain English, and Germany would remain German. Most importantly, England and Germany would be much less prone to crisis. In Europe, blame for modern crisis is laid squarely at the door of refugees and migrants. In the United States, white nationalism is resurgent, as memories of the post-war boom are increasingly associated with a simpler, whiter, and less “woke” America. This is often framed as a critique of capitalism; yet it is a primitive critique that promises something even worse — ethno-capitalism.

Numerous nations have undertaken the process of shaping themselves in Europe’s image with renewed enthusiasm. Yet two particularly stark examples of this drive stand out today. These are those of Israel and India. The former’s attempt to create a Jewish ethnostate on historical Palestineis powered by European beliefs that Jews are entitled to self-determination, along European lines. Equally in India the rapid spread of Hindu hegemony. In reality Hindus are an extremely diverse group with little in common by way of practice or identity. But they are cultivated to become a ‘people’, whom the Indian state ought to represent. Effectively relegating Christians and Muslims to being second-class citizens. It becomes increasingly critical for us to learn from European history, lest we be doomed to repeat and reproduce it.

Israel

The legitimacy of contemporary Zionism, stems from three principles. The first is that the Jewish people constitute a nation. Historically, this was far from deterministic. Hobsbawm wrote on the self-perception of German Jews as German, and the drive to assimilate into European society that existed as one of many political tendencies in western Judaism. That resulted in a schism between western and eastern Judaism. Herzl’s Zionism came not from the antisemitism of Poland, nor even from Germany. It was an aftermath of the Dreyfus affair in France, despite the Third Republic being a liberal nation, and an explicitly civic form of nationalism. The ethnogenesis of the Jewish people was forced upon them by “white” Europeans.

The second principle is that being a nation, the Jewish people were entitled to a Jewish state. Europe’s bloody history is once again rendered relevant. It was precisely this marriage of the nation and the state that inspired and legitimised the countless ethnic cleansings and genocides in a new Europe, reorganising itself into ethnostates. Mark Levene describes the genesis of nation-states in Europe as a harbinger of Jewish and Palestinian disasters: “What is the common denominator”, he writes “in this wretched litany of genocidal expulsions and deportations?” He replies “nationalism”, and the attempt to apply it in regions where it went against the grain of actual, lived human reality. Something which could only be done by extreme violence._ The European associations of nations with states resulted in the most absurd violence being inflicted upon those communities that lacked a land that they could be deported to: diasporic European Jews, and the nomadic Roma people. Ironically, the Zionist entitlement to statehood appears to have helped elevate contemporary Israelis to being, in the eyes of the West, a “civilised” people: an acceptance that still eludes the Roma.

The final principle behind contemporary Zionism is that the Jewish people were entitled to a state in historical Palestine. Consequently, the Nakba became a reproduction of the same patterns of nationalist violence that tore Europe apart in the 20th century. One with a clear expansionist undercurrent, to accommodate the growing settler population. Thus, the carving out of a Jewish state in Palestine by the British Empire, then seen as an admirable solution for Zionists, and ethnonationalist European nations happy to be rid of their Jewish populations. This contextualises (not excuses) David Ben-Gurion 1941 description of the replication of the patterns of mass expulsion in Europe as “a practical and […] secure means of solving the dangerous and painful problem of national minorities”.

Today, critique of Israel as a settler-colonial state hinges on this third principle. The Arab world has rightfully never accepted the British partition of Palestine, and the ethnic cleansing that was the Nakba. Yet Zionism’s capacity for violence stems from Israel’s birth as a Jewish nation in the first place. Today, rejecting the one-state solution in Israel stems from the desire to maintain the fundamentally Jewish ethnocentric character of the Israeli state. The never-ending land grabs in the West Bank by Jewish settlers, as well as the genocide in Gaza, are enabled precisely by the firm attachment of Israel to the notion of “a state for a people”, and the hubris to believe that a people without a land are necessarily entitled to one.

India

The steady march of Hindu nationalism in India has many parallels with Zionism. The causes for the rise of Hindu nationalism are myriad and complex. What is important to highlight, however, is the discursive role that ethnicity and nationalism play in India. A direct comparison of Hindu nationalism to early European ethnonationalist projects is, at first blush, irrelevant. After all, India is an extremely diverse country. Indeed, true European-style linguistic nationalism was never hegemonic in most of India — the average Indian city is, for instance, more ethno-linguistically diverse than its European counterpart. This is not accidental; the conditions in which modernity emerged in India were vastly different to those in Europe. Moreover the Indian bourgeoisie and the Indian state were shaped by the British Empire. English thus became the language of administration in modern India, and opened up a vast market for the emergent bourgeoisie. The Indian superstructure has therefore simply never required widespread ethnolinguistic self-differentiation.

Yet, the relative lack of ethno-linguistic violence does not imply an immunity to ethnic violence. This is best exemplified today with the startling success and dominance of the ideology of Hindu nationalism. This is an an ideology that, contrary to Hindu narratives, is definitionally an extremely contemporary one, because the notion of nationhood itself is extremely contemporary. Hindu nationalism does not attempt to create a theocracy. Actually one of the movement’s key idealogues, VD Savarkar, was an atheist who took a very dim view of many mainstays of upper-caste Hinduism, such as beef taboos.

The Hindu nationalist project attempts to bring about the *ethnogenesis* of the Hindu people. It is largely predicated on the belief that Hindus should constitute a people, or a nation. This is therefore a modernising project. To harmonise the ‘Hindu people’ across ethnolinguistic group and (nominally) caste. It involves the spread of Hindi as a dominant language all over the subcontinent. There is no genuine commitment to abolishing caste, but rather the integration of caste into a modern capitalist machinery, driven by dispossession and expropriation. India, as imagined by Hindu nationalists, should transform into a “state for the Hindu people”. A people who, hitherto, have had no state of their own. Unsurprising since both Hindu people and nation-states are a recent creation. The land that this state is entitled to is, at best, the present Indian state, at worst, it includes modern Pakistan and Bangladesh as ‘historically Hindu lands’.

Thankfully, India lacks the third principle driving contemporary Zionism. Contemporary Indians are (with caveats) not yet settlers. Yet this is cold comfort to the millions of Indian Muslims who face persistent racialisation, segregation, and state violence from the formidable Indian state machinery. “We gave them Pakistan” the Hindu nationalist talking point goes. “Why can’t they just go there?” This is not very different to an Israeli settler wondering why the Palestinian booted out of their home doesn’t simply go to Jordan or Egypt.

It is impossible to imagine the sheer scale of violence that efforts to (re)build ethnostates would enable, all over the world. Yet we are encouraged to ignore both real and potential violence, and accept it as somehow “necessary” to stabilise modern nation-states. It is this idea that allows liberal Zionists to defend Israel’s history of ethnic cleansings — “Everyone did it, so why can’t we?” It is this that allows Hindu nationalists to claim that mass deportations of Muslims are essential to maintain India’s fundamentally “Hindu” character.

All nation-states are bad, but some are worse than others. It is time, for the left to assert that the European model of nationalism, far from being the “most natural unit”, has been responsible for unprecedented scales of violence. Nobody — not Germans, nor Jews, nor Hindus — should be entitled to a land for their people, and we must have the honesty to acknowledge that no long-awaited socialist revolution can ever emerge from the immensely artificial, parochial and myopic cultures that these tendencies enable.