Berliners who lack intimate knowledge of what locals call “Görli,” along with far-off Germans who for decades have been spoon-fed lurid accounts of the “notorious” place (in 2015, the Stuttgarter Nachrichten called it the “drug park of the nation”), favor Wegner’s approach.

Think again! OUR GÖRLI STAYS OPEN!

I have previously written about initiatives for affordable rents and on gentrification projects in Berlin and especially Kreuzberg, where I’ve lived for more than 20 years. Now I’m writing about the fight over my park. Although usually presented differently, this, too, has to do with replacing parts of the population with people who have money.

“Görli” is a people’s park. Berliners – and visitors – go to Görli to pet donkeys and fondle each other, play football and “black light” minigolf, grill with the whole big family, chill watching the sun set, ride bikes, jog, pick berries, study birds, gather for a film or a beer, innumerable children’s festivals, May Day parties, la Fête de la Musique, a free Peter Fox concert for 12,000… Görli is a destination in guidebooks and on walking tours.

Görli is the trampled green lung of “SO36,” that eastern part of the district of Kreuzberg whose pre-reunification “ex-centricity” drew Germans avoiding the (West German) draft to experiment with alternative lifestyles, and “guest workers” in need of affordable housing – which was mostly in very bad shape.

SO36 spawned numerous intercultural and art projects as well as the movement to squat run-down buildings and collectively refurbish them. SO36 residents also successfully resisted plans to construct a highway that would have ripped out its heart.

It all began with Görlitzer Bahnhof…

where trains departed for the eastern towns of Cottbus and Görlitz and delivered cloth, bricks, glass, and coal to the capital. The station built in 1866 spurred the development of new urban neighborhoods whose streets were named after cities along the railroad: Liegnitz, Ohlauer, Oppelner, Sorauer (now Polish Legnica, Olawa, Opole, and Żary), Reichenberg (Czech Liberec), and others; the station square was named after the Berliners’ favorite getaway, the Spreewald.

The elegant station building was heavily damaged in World War II; passenger train service was ended in 1951. Train tracks were removed and coal and gravel heaped on the wasteland. Old cars piled up and leakage from a scrap-metal press contaminated the soil. Repair shops, a hairdresser, a newspaper kiosk, a mosque, an arts center, and even some people moved into the station.

Then, in 1975, according to Werner von Westhafen in the Kreuzberger Chronik, “public authorities feared that the ensemble might provide a haven for anti-social elements”* and demolished most of what remained. However, the area sorely lacked public parks, and the open space was used for recreation. A children’s “traffic school” was built along the perimeter in 1976, a petting zoo in 1981. Freight service between East and West Berlin (the Wall ran along Görli’s southern flank), continued till the mid-1980s. In 1989, the international performance group Mutoid Waste Company pushed their towering scrap-metal “Käfer [Beetle] Man” and Bird of Peace over the canal bridge onto DDR territory – forcing East German soldiers to open the wall.

From 1978, residents fought to have the 14-hectare site turned into a public park, which was key to raising the standard of living in Berlin’s smallest, most densely populated district. Numerous neighborhood groups took part in its development and in the 1984 design competition. The park had to offer a variety of activities and spaces for playing and relaxing. It was also supposed to make the history of the site visible. In 1986, construction began.

Residents wanted their park to reflect the neighborhood’s character, and in 1998, acknowledging its many residents from Turkey, a fountain inspired by the Pamukkale limestone formations was added. Unfortunately, the designer chose a stone incompatible with Berlin winters: the artwork quickly crumbled, unleashing a long legal battle. The area is now used as an informal amphitheater.

According to a brochure published by the district in 2013, “The history of Görlitzer Park is […] one of overload and negotiated compromises. For too long, the area […] was where all the wishes that could not be fulfilled in the densely built-up residential areas were focused: sports areas, mosque, allotments [….] The park has always been too small for all this and only functions by everyone working together.”

For a very long time, they have. Görli has a special, very relaxed, atmosphere that attracts a huge number of different individuals and groups throughout the day and night.

But Berlin’s mayor and the new better-off neighbors seem to not know or want to understand that local residents have been closely involved with Görli for decades. More recent initiatives range from making the park clean and “drug-free” in 2008 to creating a place for nature and environmental education and planting fruit trees in 2010, and special child/parent groups to develop more activities and redesign the “pirate ship” playground in 2011. There is even a park council. Some 30,000 Kreuzbergers can reach the park in 10 minutes. We identify with Görli. Görli is ours.

First came the drugs….

Over the years, Görli has attracted not only neighbors but also other Berliners and tourists, too, including drug dealers, whose business has flourished as other Berlin areas have been “cleaned up.” Numerous countermeasures, including cutting back undergrowth, sending in more police, and a short-lived “zero tolerance” policy of prosecuting even small amounts of drugs that were legal elsewhere, proved futile.

And then…

in June 2023, reports of an alleged gang rape and robbery set off Berlin’s new conservative government’s law-and-order response. Two homeless, unsuccessful asylum seekers from Africa were arrested, along with a third African man with a temporary residence permit who was living with his pregnant partner. But first the presumed victims left for Georgia without notifying the authorities. Then a short video surfaced of a white woman having consensual sex with a black man and a light-skinned man who appears to be her husband. One of the accused testified that he’d been offered money to have sex with the victim, whose account conflicted with the medical report. She was never questioned conclusively, and it is not sure that her husband was in fact robbed. Because Germany has no mutual legal assistance agreement with Georgia, in February 2024, pending the victim’s testimony, the three accused men were released from custody and the trial suspended.

What’s this about?

According to statistics, in the first six months of 2023 there were six rapes in Görlitzer Park and Wrangelkiez to the east. Five were committed in hostels, apartment buildings, and a shop, one in the park. And some of the rape cases involved people who knew each other. So much for the threatening (Black African) drug dealers in public spaces. Rape figures have remained stable in recent years and three times as many crimes occur outside the park as in it.

But facts don’t stop certain parties from warning that Görli is a security risk. For decades, Görlitzer Park and Wrangelkiez have been described as a “crime-ridden area” – one of six such areas in Berlin – where the police can control a person’s identity, search their possessions, and even do a body search without having any specific grounds for suspicion. Park patrons happen upon such “racial profiling” in and around Görli every day.

Rapes also occur in other parks in Berlin. But inconclusive charges sufficed for the mayor to schedule a “security summit” to discuss Görli and Leopoldplatz (in Wedding). Following that, Berlin’s official website announced new activities involving “city government and the districts, the interior and justice departments, prevention and policing […] to combat crime and increase security.” There would be more accommodation and drug-consumption facilities, better maintenance of green areas, increased police presence, up to five days of preventive detention, and video surveillance. Berlin would expand its definition of organized crime to include money laundering, narcotics and arms trafficking, and henceforth investigate crime structures, cryptocurrencies, and new business models. The city would emphasize prevention and programs to help people stay out of organized crime and those in it to get out.

Parts of that plan may not sound so bad…

But it included one dreadful idea: fencing off Görlitzer Park. Erecting lockable doors at all entrances and two huge steel gates at the canal. Replacing some existing wall (much of the original brick wall nearly encircles the park) and building new fences. Installing floodlights to illuminate the park all night. Clear-cutting bushes and underbrush. Closing the park from sundown to sunrise and “if need be,” during the day as well. At the cost of more than €2 million and another €1 million per year to guard the locked park. At a time of constricted budgets, these funds are most likely to be diverted from sorely needed social projects, including those related to drugs.

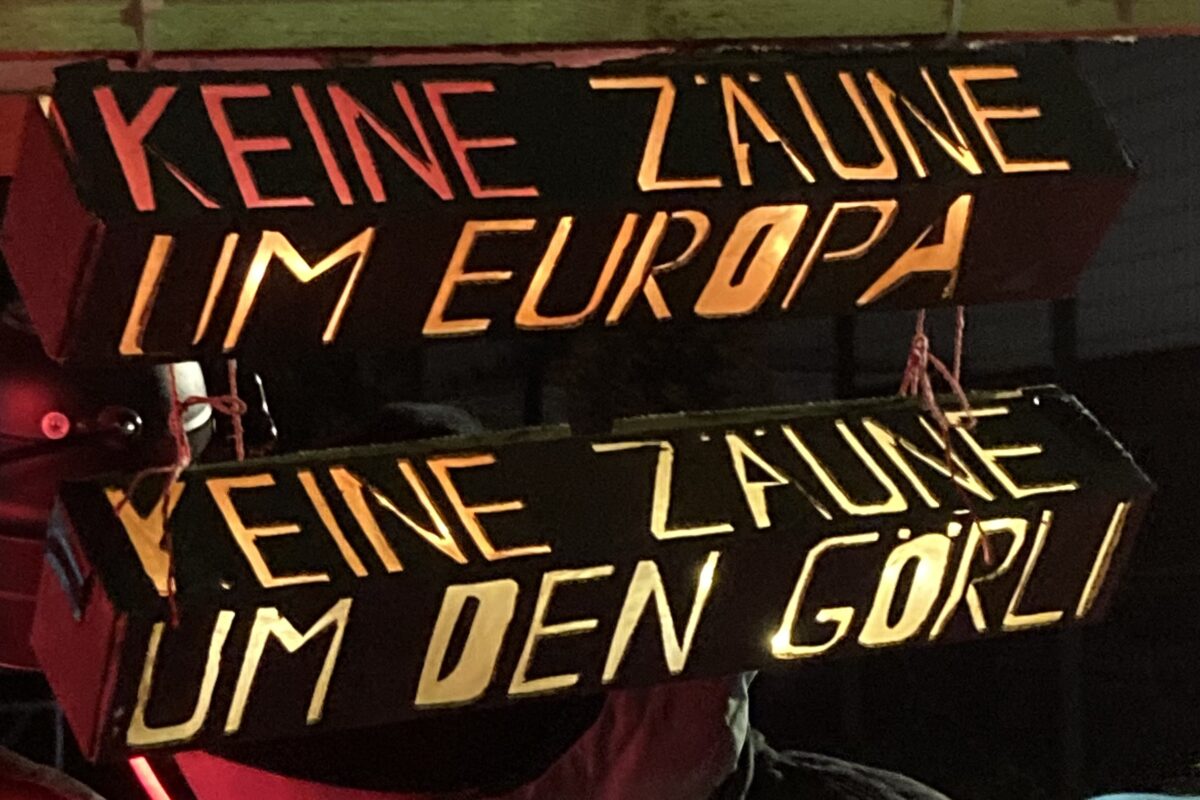

People who live near Görli and often use the park are horrified. They want it 24/7. They demand social programs and housing for needy park users. Once again, Kreuzbergers have organized in a large number of initiatives, including Wrangelkiez United (with a 13-minute film with those affected by racial profiling),** Görli 24/7: Unser Görli bleibt offen (“Our resistance is motley, creative, diverse, and defiant!”), Görli Zaunfrei; Bündnis für Soziale Sicherheit (“Solidarity instead of law and order!”), and many more.

These groups say the park is for everyone who uses it – not just local residents. They condemn racial profiling and see the issue as the fruit of decades of stigmatizing Kreuzberg SO36 – and the district’s galloping gentrification. In Reichenbergerkiez to the west, luxury condos are being built inside the large courtyards [see my article]. Potential buyers are offered a “pulsating” trendy neighborhood and pricey retreats behind locked gates. Then the new deep-pocketed residents discover drugs, poverty, and unhealthy people in the neighborhood.

But not only do long-time residents often personally know the drug users, and the poor and ailing people in their streets, they also know that locking Görli will push all the dealers into the surrounding streets. They understand that many drug dealers and consumers are homeless and that allowing them to work legally would cause many to leave the trade. Opponents of the fence also place the problem in the context of walls throughout and around the European Union. A mobilization video proclaims: “Berlin doesn’t need more limits and exclusion. Where they build walls, we build a staircase!”

Neighborhood associations and ad-hoc groups have hosted discussions, run guided tours, organized demonstrations, and mounted poster campaigns (“Our Görli Remains Open!”) attacking the mayor’s short-sighted plan to fight crime that will principally deprive them of their park. The district went to court to insist on its legal authority over Görlitzer Park, lost at one level, then had to wait for the Higher Administrative Court of Berlin-Brandenburg to rule on its appeal. Despite announcements that fence construction would begin in June, the Berlin Senat also waited.

Meanwhile…

To prepare for the eventuality that the fence would be authorized, in early September, an “action week” kicked off with an evening of local TV reports on the 2009 action to prevent former Tempelhof Airport from being developed: “Have you ever squatted an airport?” Throughout that day, some 6,000 people approached different sections of the airfield’s fence with humor and determination, repeatedly forcing the police to regroup. Only two managed to get in – but the initiative took off. In the “100% Tempelhofer Feld” referendum of 2014, 64.3% of Berliners voted to ensure that the entire – immense – area will remain accessible for all. With humor and perseverance, Berliners won a major battle against “development” and created a fantastic new public space.

Mayor Wegner is also challenging that success… but that’s another story. For now, the history of Tempelhofer Feld inspires Görli’s defenders.

In a “social summit” held Tuesday, 3 September, local activists and experts addressed some of the major problems that cannot be solved by building a fence with the money needed for social services. That will merely exacerbate them.

Astrid Leicht of Fixpunkt e.V., whose social workers and medical support staff work “to reduce harm and prevent infectious diseases,” explained that the drug scene in Görlitzer Park had grown as a result of increased policing on Leopoldplatz and along the U8 subway line: dealers simply shifted there from Kottbusser Tor after its new €3.24-million police substation opened.

Moro Yapha, “an advocate for migration and human rights,” described the overwhelmingly young African men in Görli, many of whom had had fairly settled lives before losing their apartments or being denied asylum. They didn’t come to Germany to deal drugs, and do whatever they can to financially support their families in Berlin and Africa. Moro wants the positive stories of the dealers’ different cultures and languages to be heard – in a new meeting space. But he also explained that many dealers have become users and urgently need therapy and other social interventions. “A fence and police and security are not the solution. We have social problems and we need a social solution.”

Dirk Schäffer, a consultant on drugs and the criminal system, pointed out that the situation in Görlitzer Park is not unique! Parks are some of the few places where drug addicts can meet. However, these days a lot of cocaine is being smoked in Görli. It’s also used to prepare “crack” and “freebase,” which give faster and more intense highs that are quickly followed by terrible lows. Crack is very addictive, putting users at risk of lung infections, depression, aggressive behavior, paranoia, and schizophrenia. Besides that, the Görli crack users are homeless: they need places to sleep during the day and supervised sites for regulated consumption 24/7. “An illegal environment makes you sick.”

Feminist urban researcher Stephanie Bock addressed “security” and “fear” and the focus on spaces perceived as places to be feared because they lack security infrastructure. She attacked the supposedly feminist analysis: “Women are afraid of violence and violence is a problem: not just for women but also for People of Color and people with disabilities, in Kreuzberg and Tiergarten, too. We have to identify the real problem.” Failed social, immigration, and drug policies compounded by cuts to social facilities and services.

Bock described Görli as a public green space, an “expanded living room” that visitors use for a variety of reasons, including as a safe haven. “A park connects.” Parks can be organized to accommodate different wishes and needs and ideas: “It’s not about closing the park, but rather opening it.”

Criminologist Tobias Singelnschein from Frankfurt wondered out loud why Görli is a “dangerous place.” Over the last 20 years, middle class security has become a bigger and bigger issue, with politicians and the police attempting to objectively solve what are actually subjective concerns about security. “The discussion about Görli and crime has taken on a life of its own. However, when many police are present, there are also many offenses.” In fact, most of the violent offenses occur outside the park. So much for Wegner’s purported “drug and crime problem” in Görli. Most of the offenses there involve drug dealing, immigration law violations, and theft. “Crime” covers many phenomena with many different causes, says Singelnschein. “We have to put aside the misplaced assumptions regarding Görlitzer Park and recognize that there is no quick fix: a fence will only lead to displacement. Instead, we need to discuss both the sense and purpose of police activities within the district and throughout Berlin. Thinking that crime can ever be eradicated is a fallacy.”

Katrin Schiffer from the Correlation Network that studies “drug use, harm reduction and social inclusion” in Amsterdam sent comments about the danger of instrumentalizing groups like drug users and homeless people who, instead of being marginalized and stigmatized, need to be protected. “That takes real, not symbolic, civic participation.”

We know what’s needed. We “get” the problem. It’s structural: unequal opportunity, the prohibition of migrants working legally, neighborhood gentrification, and the cuts to social services that are impoverishing parts of the population.

The 200,000-member German National Cyclists’ Association (ADFC) also weighed in on the subject, criticizing any nighttime closure of the well-used route that cuts through the park for forcing pedestrians and cyclists to take a 700-meter detour – which is definitely not safer.

Beyond these critical social and security issues, thinning or removing existing vegetation “including the roots” (!) to improve visibility for the police would entail massive ecological damage. BUND, the grassroots nature conservation and environmental protection NGO, issued a position paper that describes Görlitzer Park shrubs and undergrowth as breeding habitats for a variety of birds, refuges for fauna, and food sources for birds, insects, and small mammals. They’re also hunting grounds for seven species of bats.

The BUND further notes that floodlights damage trees, and that police and park patrollers have not prevented drugs being dealt in plain sight. Different lighting and extreme pruning “would just harm conservation efforts and reduce visitors’ pleasure in the park instead of minimizing crime.” It adds that ugly clear-cutting and reduced biodiversity would create a less pleasurable park experience and make it less attractive for other social groups. Instead of making Görlitzer Park safe, Wegner’s measures would increase the proportion of drug dealers and users to other visitors. The NGO demands detailed explanations of the plan, a “comprehensive species conservation report and a sustainable lighting concept that protects species.[…] The urban nature in Görlitzer Park must be resolutely protected and maintained.” It notes in passing that targeted maintenance could eliminate the need for radical interventions.

As Görli’s neighbor, I’m also bothered by the thought of the light pollution that all-night illumination would cause. In my backyard that’s just a hop, skip, and a jump from Görli, I love to gaze at the star-studded night sky. In many cities, that’s not possible. Wegner’s plan will dim Berlin’s stars. How dare he? (And by the way, the current lighting along Görli’s footpaths is very attractive.)

Let us not forget that Berlin has become the hottest state in Germany. More environmentalists should get involved in fighting this untenable, unnecessary, and unaffordable project.

All these issues came up on the walking tour of the park on Friday, 6 September. The action week also included one evening of historic videos and reminiscences about the park’s history, another of films about racial profiling and how different cities ensure affordable housing (Berlin looks very bad in comparison), a picnic, a demo, and many opportunities to discuss the way forward. The week’s high point may well have been on Sunday when a few hundred people playfully rehearsed future protests: throwing biodegradable paintballs, writing poems, breaking through a fence and canoeing across the canal to find a bolt cutter.

Not even three weeks later, on 24 September, the state’s Higher Administrative Court ruled that Kreuzberg lacks the authority to use an urgent procedure to fight the fence. It did not rule whether or not the district has a legal right to take action against the Senate. That requires more litigation.

This is not the end of the fight for Görli. Join us.

© Nancy du Plessis 2024

*All quotes are my translations.

** Ignore the terrible automatic translations!