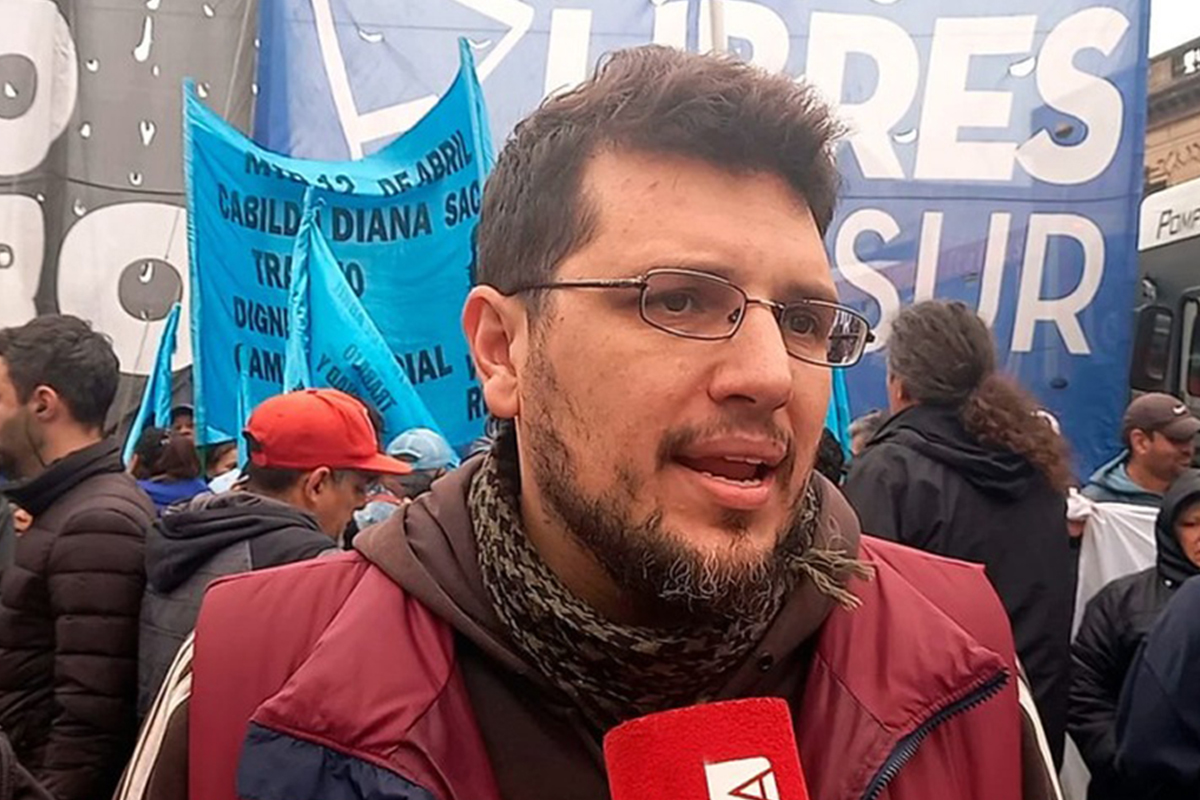

Charly Fernandez is an Argentinian activist and a member of FOL (Frente de Organizaciones en Lucha), a social organization dedicated to empowering the most marginalized families within the Argentine working class. FOL strives to self-organize and advocate for the rights of these families, aiming to improve their material, social, and cultural conditions of life.

Since the election of Javier Milei, who is known for his feverish anarcho-capitalist fantasies, there has been a widespread media and discursive campaign against social organizations. The attack has been centred on the belief that individuals receiving social aid do not work, painting them as barriers to Argentina’s efforts to overcome its socio-economic challenges.

Nevertheless, FOL remains steadfast in its goals, which include advocating for fair employment with decent wages and working conditions, promoting gender equality, the emancipation of women and dissidents, and fighting for improved access to healthcare, education, housing and suitable living conditions. Additionally, FOL is committed to defending the rights of indigenous peoples, children, and youth, as well as advocating for human rights, access to culture, and recreation.

Tell us more about you and when you started organizing and advocating for the rights of the marginalised.

I have been an activist since I was quite young. I started during the process that began in Argentina with the 2001 assemblies. This was during the closing of the convertibility cycle, the first wave of strong neoliberal measures, and globalization.

Argentina’s exit was an exit from a lot of social conflict – very different from what is happening now. At that time, there was a tendency towards the left, where people began to register in popular assemblies, factories were taken over, and soup kitchens and work co-operatives were organized.

It was a time of great political participation, and I was one of those young people who began joining resistance assemblies. We started organizing ourselves in a situation where our neighbors and families suffered the consequences of years of neoliberal policies and unemployment.

How was the political movement at that time? How did it evolve?

These assemblies rotated from more central locations to neighborhoods and the countryside, especially the city’s shantytowns. However, my activism was in Buenos Aires. The process in other provinces and even in the Buenos Aires metropolitan area was different, so we began to form a link with comrades who came from movements of unemployed workers who had started to organize long before.

From that experience, I became involved with a group of comrades until we formed FOL, Frente de Organizaciones en Lucha. This front is a mix of movements: the MTD (Movimiento de Trabajadores Desocupados), the MTR (Movimiento Teresa Rodríguez – also an MTD), and others. We are talking about the year 2000, 2001.

Today, we continue to build our organizations, but now we are in almost all the country’s provinces. We have developed work co-operatives where many comrades work, from services to productive units to housing. We also have comrades who live in rural environments, and in these cases, there are also food production co-operatives and other types of things that do not exist in the cities.

How is it today?

Today, social movements, and we, in particular, do complex territorial work. It is not that we only attend a soup kitchen or a popular dining room. We have a framework of different spaces of intervention and spaces of health, gender, and environment that promote rights and articulate struggles.

For more than twenty years, we have been winning partial victories, and from those partial victories, we have been winning rights that have often been transformed into devices or public policies.

Are these organizations an alternative to what the State should do and provide for the people?

The lack of fundamental rights for colleagues to join the formal labor market and access to housing or health means that social organizations begin to take over this role. Many times, we’ve been accused of being a “para-state” or an outsourcing of the state. But what happens is that if we are not there? There is nothing. In reality, the alternative is narco-criminal gangs, as has happened in other places in Latin America.

One of the things that we are discussing today with all politicians is: look, the pandemic showed it. If social movements are not building territory, building community, and being part of the social network, there will be narco-criminal gangs. We, the social organizations, have limited and have acted as a barrier against the development of these gangs. The most robust movements are rural rather than urban.

Do you see parallels between Argentina’s form of social organization and other social movements in Latin America?

I have had the opportunity to travel to other countries in Latin America and talk to comrades about this. The role that we play is not against the government apparatus. The problem is that there is a territorialized, armed, millionaire force (narco-criminal gangs), and the state is impotent. So, what we tell them is: do you think that the drug traffickers are going to intervene, and then they won’t try to play in politics and to try to lead the country or lead states?

That is what happens in many places in Latin America. We see that there is a minimum democratic consensus, the understanding that organizations are not part of the problem but rather part of the solution.

What is the situation of the social movements in Argentina and Milei?

We have achieved family allowances, access to resources on gender violence in companies, education, and financing for building popular neighborhoods. All these were achieved not because of the goodwill of the government in power but because there were comrades who died fighting in the streets for this.

They call us the “CEOs of Poverty.” We are “poverty managers.” That is the problem, isn’t it? But, if one looks at how the picket movement began, how the social movements began, and all the rights that have been achieved in the neighborhoods over the years, of course, they want to destroy us.

There was a minimum wage, and the only thing we did was raise the salary ceiling during all these years. We have achieved family allowances, access to resources on gender violence in companies, education, and financing for building popular neighborhoods. All these were achieved not because of the goodwill of the government in power but because there were comrades who died fighting in the streets for this.

And, well, this is what the political class, the establishment, and the capital seem willing to do: destroy and eliminate these rights. Milei has been sent to execute this plan. But if we ask other sectors of politics, they will say exactly the same.

Is there a possibility of co-operation between these movements from below? Does it make sense to co-operate, even with these structural differences?

It is necessary. There is a clear coordination of the global far-right. It’s not a coincidence that Milei comes to Spain to meet with Vox (the ultra-right party in Spain), goes to meetings in the United States, or is invited to Austria to receive an honorary title.

All these societies and think-tanks are part of the apparatus of these digital militias — devices and networks created to fight a cultural battle of aggression and social control.

There is co-ordination, a kind of global far-right international acting, financing itself, and taking over states where they can. And they are saying it everywhere. Milei said it in Davos: we must break with everything progressive, gender culture, ‘woke’ or whatever you call it.

What is your wish or hope for the international left movements and the ones in Germany? How can they show solidarity with the popular movements in Argentina?

We see that there are no such networks of articulation on the side of left-wing progressivism. If there are, they have become old, bureaucratized, and institutionalized, as we see in the social movements in our region, Latin America, and here in Germany. We need to strengthen those ties. The advances we achieve in Argentina, or those achieved here in Berlin or Brazil, will depend on the levels of resistance we can build.

We must build on the idea that ”if they touch one of us, they touch us all,” an old slogan of the international left, emancipatory movements, and national liberation. All movements try to survive, resist, and face daily state repression battles. But we must undertake this task because this is on a global scale.

The mission now is to talk with other comrades and ask ourselves: How do we build a roadmap, understanding our origins and the different ideological perspectives in the international movement? This is a central task.

We are strengthening ties with the comrades of El Bloque Latinoamericano in Berlin, obviously because we are close. Many of us have been activists, and we have known each other and our comrades in their countries of origin. Our actions range from concrete aid to raising awareness about what is happening in Latin America.