Hello, Henry. Thanks for talking to us. Could you start by introducing yourself?

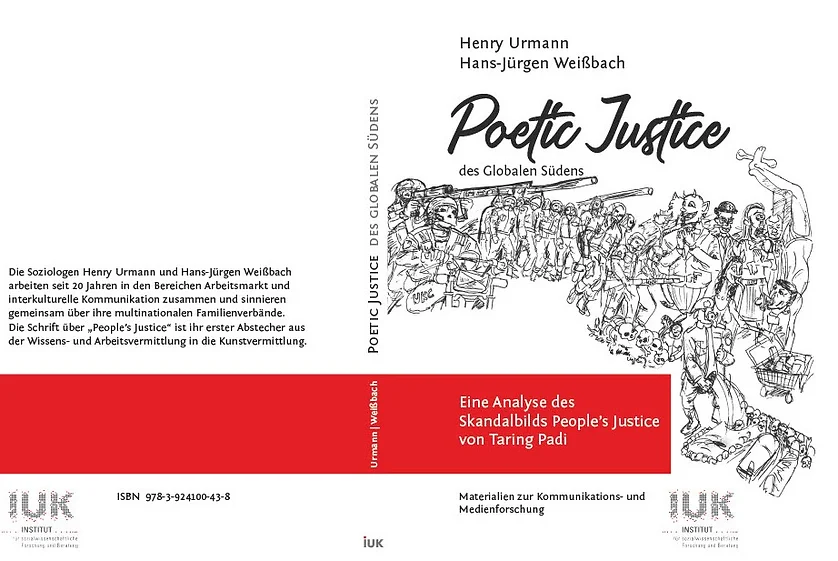

My name is Henry Urmann. I live in Frankfurt. I am married to an Indonesian woman and that’s how I took an interest in Indonesian culture. As many others, I was outraged by the—I have to say—xenophobic media and political response to the documenta fifteen. With a dear friend, Hans-Jürgen Weißbach, we started to do some research and published our book last year. We also started a blog, www.peoplesjustice.de. And hopefully next year we can hold an exhibition to show and explain the painting to the German public.

The so-called “documenta scandal” has suddenly come back into the news in Germany, after the government justified pushing through an antisemitism resolution because of “antisemitic scandals like those of the Berlinale and documenta”. For people who haven’t been following this, what happened at Documenta?

At documenta, Indonesian artists, the Indonesian curators and organisers were accused of antisemitism, and it was claimed that several pieces of art contained antisemitic visual code. The explanations of the curators and artists were not taken into full consideration.

The painting that caused the outrage was created by the Indonesian art collective Taring Padi 20 years ago. Members of Taring Padi were participants in the democratic overthrow of the last dictator of Indonesia in 1998. At the documenta they were pressured to remove this huge painting of 100 square metres which was in the middle of Friedrichsplatz in Kassel. In the documenta exhibitions before, the artworks which were placed in Friedrichsplatz became part of the art canon so this was really significant. Removing works of art is something that authoritarian governments do. It was a blatant act of censorship that we had to wrap our heads around.

How did German media and German politics react to the mural?

Without further investigation, they repeated the most superficial and raw accusations against People’s Justice. This was to be expected from the notorious Bild Zeitung, but what was fascinating and shocking was that the allegations were also expressed by the left liberal media, like taz, Frankfurter Allgemeine or Süddeutsche Zeitung.

People who would usually be seen as moderate and even very progressive participants in the debate, like Meron Mendel, took a hard line against this painting and accused the whole of documenta of having an antisemitic atmosphere.

Specifically, the accusation was that part of the mural had antisemitic content. What was your answer to that accusation?

It remains a tricky thing to depict a Jewish character with the insignia of the SS. I am convinced that it was painted with a very provocative intention to display the realities of a nasty world where victims like Henry Kissinger who lost a big part of his family in the Holocaust can become monsters while they fight their monsters.

What happened next was that not just Taring Padi were banned—there was also censorship of other artists who were exhibiting at Documenta. How did that happen?

Taring Padi were not completely banned. They still held a big exhibition in the Hallenbad Ost. But other artworks were also criticised. There were demands to end the documenta completely and demands to remove other pieces of art for being antisemitic.

And there was a public hostility towards the community of foreign artists from the Global South fueled by German politicians. In his opening speech, [German president Frank-Walter] Steinmeier said that there are boundaries, and that these boundaries were crossed. [Author: Steinmeier accused documenta of “thoughtless and reckless approach to the State of Israel.”]

The artists and other participants of the opening event were appalled by this initial statement and the climate it helped to create. The British artist Hamja Ahsan expressed this when our chancellor, Olaf Scholz refused to visit documenta.

How did you get personally involved?

Our friends in the German-Indonesian community in Frankfurt were quite upset about the behaviour of the artists themselves. They criticised the artists for not defending themselves in response to the media coverage. They found the artists’ response to be too weak and also dishonest. This viewpoint is also shared by some people who were working at documenta. They said there was a lack of contextualization and of explanation.

They were also outraged, of course, at the accusations of antisemitism. These accusations did not only relate to the artists and the artwork, but also to the whole community. My friends were shell shocked by the turn of events, the statements of Steinmeier, and the defamation of the artists and the artwork.

After we talked about it in our circle of German-Indonesian friends, I started researching a little bit deeper into Indonesian history. I looked at the People’s Justice painting, and I had an idea. The painting depicts concrete historical figures, like Henry Kissinger, Muammar al-Gaddafi, and Queen Elizabeth. That helped me to understand the painting, but also the strange reaction of the artists.

In the book, we first focus on everything that is depicted in the painting. It contains so many references to art history, Pop Culture and the Indonesian understanding of their history and world history after World War Two.

So we explain what’s depicted in the painting, the whole narrative. We explain the historic context of when the painting was made, following 9/11 and during the war on terror, which began in Afghanistan. We explain how this played out in Indonesia at that time. We also talk a little bit about the artists, the Taring Padi collective and their friends and the whole art scene there.

We also give an interpretation of how this weird kind of coalition developed that we see now, between the Springer Presse and the ‘woke’ Left came into being.

Do you see a parallel between what happened at documenta and the current discussion about ‘cancel culture’?

Definitely, it’s part of cancel culture. I think Salman Rushdie explained very well in his speech last year about the cancel culture that comes from the Left and from the Right.

Do you think it’s the same thing? Do you think the Left and Right are as bad as each other?

I think that while the right-wing cancel culture is an authoritarian response to the current crisis, this left-wing cancel culture which has a bit of a Kamala Harris vibe, but is also fueled by this specific German arrogance and sense of superiority. We call it politisch-korrekte Fremdenfeindlichkeit in our book, ‘woke xenophobia’ you could say, stereotyping people from the Global South with misogyny, authoritarianism and antisemitism.

This all happened in 2022. It was a long time before October 7th. How do you think attitudes in the art world have changed since?

I think it’s very clear now to more people than before, that the charge of antisemitism is weaponized against opinions and art that does not fit into a certain narrative.

Surprisingly enough, even Stefan Ripplinger, one of the early anti-Deutsche who was co-founder of Jungle World, shared our interpretation of the painting in his new book, Kunst im Krieg. He clearly says now that the charge of antisemitism is weaponized—I know that even people in the Green Party see that this is happening in the parliament, and it’s happening everywhere.

Do you think this is a specifically German thing?

No. It’s also happening in the Anglo-Saxon world, just look at what Donald Trump plans with the universities.

What do you think the role of an artist is during a genocide?

The painting People’s Justice is dealing with the anticommunist genocide of millions of innocent civilians that happened in Indonesia in 1965, 1966. A mass murder programme with the complicity of the western powers and under the cover of the western media. Does that sound familiar?

Reflecting on this trauma the Indonesian artists of Taring Padi created a strong message about the state violence in the last cold war. The painting emphasises the transnational character of the perpetrators and therefore the necessity of transnational solidarity and remembrance, it’s warning the spectator of complicity and also shows a path towards reconciliation and a future where victims and victimizers can live together peacefully again.

Going back to the question about what the artist should do, art is never simplistic and does not contain only one message. Art is the effort to turn something bad into something good. I think what always changes in times of crisis is that in good times, an artist sees life through the lens of art. And In a time of crisis, you see art through the lens of your life. You may come to different conclusions.

Documenta is a long running institution. The event in 2022 was the 15th documenta. Do you think the festival can survive the scandal?

There was a struggle about the code of conduct, and it ended with a compromise, which everyone can live with at the moment. The artists are not supposed to sign anything or give a big declaration that they will do this or not do that. It was on the verge of collapse, but I hope the next documenta in 2027 will go smoothly.

Will all artists take part? There’s been talk of boycotting both documenta and Germany.

I’m a very optimistic person in general. Since the Ampel-coalition started, we’ve seen a lot of well intentioned, badly executed things going on in Germany. I can’t yet imagine that things will continue like this much longer. But of course there is a realistic danger that artists will turn away from Germany.

Although it looks like we won’t have an Ampel-coalition for much longer

For me the bigger context is what documenta and the Ampel-coalition stood for. Look, I am from Frankfurt and there we achieved to become this cosmopolitan, progressive and prospering city not with, but of immigrants. My hopes for Germany to get there are diminished for some time to come and that has to do with this xenophobic climate that the documenta scandal helped to produce.

To finish off, could we go back to where we started? Documenta was cited as a reason for the antisemitism resolution. What does this resolution mean for the progressive immigrant country that you’re talking about?

Like I said, it’s just another well-intentioned, badly executed piece of politics. I don’t know what it will bring. We had a BDS resolution that did not have a very strong influence in Germany. You can’t push out the reality of mainstream opinions in other countries for too long. It doesn’t work. Like you can’t have a Linke that is the only socialist party in the world that does not express solidarity with Palestine.

We are still excluding the world, and excluding the mainstream opinions of other countries. But people consume media from different countries. This has to be part of the German debate again, and I’m sure it will. It’s going to happen after the war and the violence come to an end, and this will come to an end.

You have said a couple of times that you’re hopeful. With everything that’s going on, how can you keep hope?

Understanding the Indonesian perspective, studying and deciphering this painting was an incredible pleasure and I was just in Indonesia, not only the weather, but also the political and economical outlook is so much brighter than here. They had the best 20 years of their last 500 years. They are looking at a bright future.

We are having so much trouble coming to terms with the fact that while, of course, the Holocaust was the most terrible event of the 20th century, decolonization was the most important one. One event makes you incredibly pessimistic, the other fills you with hope. And this is still an ongoing process.

So optimism of the will, pessimism of the intellect?

No, it’s like a double vision. Western decline is not the decline of the so-called rest of the world which is now the majority of the world. There is a prosperous world out there. We have to accept that there are not only amazing artists in Indonesia, in Africa, in Latin America, China and in the Middle East. But there are also more scientists, doctors, managers and pilots in all these countries than in Europe and USA.

We can’t unmake the past, but the future for the global majority is bright. That’s also what I see expressed in the painting.