Hi, Margarita. Thanks for talking about us. Could we start by saying a little about who you are and what you do?

Hi Phil, thank you for having me. I am a Colombian visual artist. I lived in Germany for five years, I did a masters in media art & design and worked as a teacher and researcher for the faculty of visual communication at the Bauhaus University. During my time in Germany I was involved in various migrant movements and grass root organisations that work with civic education and human rights. My work delves into topics of political violence, aesthetics of power, anti-racism and migrant communities both in Colombia and Germany.

You have a long-term project about political violence called “Arder la casa“. Could you explain a little more about this?

Arder la casa explores the contingencies of violence in Colombia through my family history and my father’s exile. In 2015, years after finishing his term as mayor of a small town bordering Venezuela, my father crossed the Colombian border fleeing the political persecution he had been subjected to for decades. I remember that he disappeared on different occasions when I was still a child, but the fairy tales my parents told me justified his absence. In 2015, for the first time, I understood the fragmentation of my nuclear family as a consequence of the political conflict in Colombia. My father’s exile marked a turning point from which this project develops. With the images, I try to travel between the past, the present and the future, unveiling our history to reveal traces of violence, mythologies, family relationships and wounds. The project uses archives such as photos or newspaper clippings, paintings, analog photography, video and sculpture.

You have moved on to depicting racist violence in Thuringen. Why did you choose this subject? Is there a connection between violence in Thüringen and your earlier work in Colombia?

The topic has always been personal, I always had an uneasy feeling while living in Germany. At first it was something that I couldn’t name properly, some sort of inadequacy that I understood as part of my character; as if something was wrong with me, perhaps my culture or my personality. It quickly developed into discomfort. Talking to friends and sharing our experiences, I understood it had more to do with how white Germans and German society perceive me than with something wrong inside me. At some point, I felt that in Germany I couldn’t concentrate on making art, not with all the noise itching around my body. I got involved with different anti-racist initiatives that were amplified during the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020. I went to marches, did speeches, got connected with people having the same struggles.

At some point though I wanted to get back to photography, I had stopped taking pictures for two years. It was a sort of creative vacuum, highly connected with the place. I did an exercise, I wanted to portrait my friends in medium format. It was an excuse to make pictures again and it quickly transformed into a project that I thought could be interesting, to photograph and interview my friends to ask them about their experiences with racism in the city. While doing this I won a grant and it became a bigger project, a traveling exhibition that showed stories and pictures in different cities of Thuringia, anti-racism workshops and lots of conversations. From then on I have worked with such topics.

What are the day-to-day experiences for refugees in Eastern Germany? How much support is available?

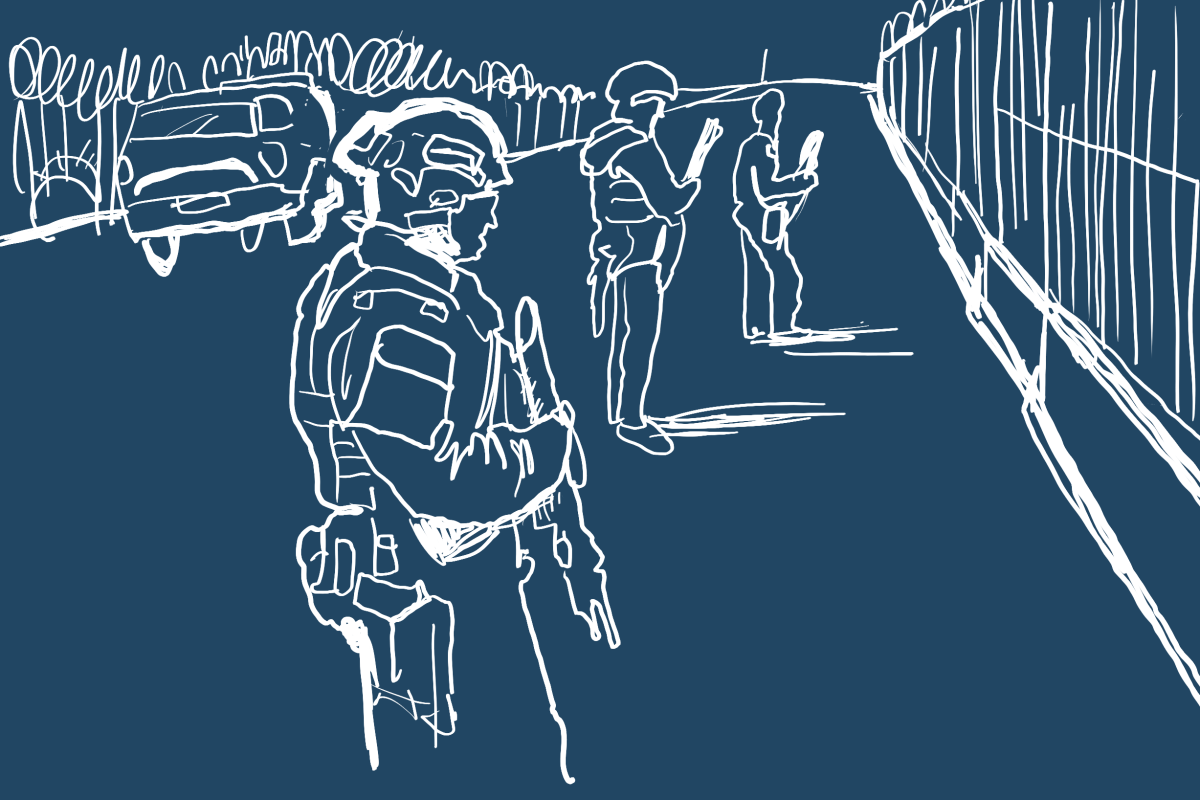

I guess this could be better answered by someone who has had the experience of living as a refugee and is active within the community. But in my opinion and having learned from my work, I think the experiences vary depending on where the person is living, wheter that person has family in the country, if they speak the language, whether they are BIPoc or white, where they come from, etc. In my experience working with refugees, I saw that refugees in Thuringen are isolated in facilities located in rural areas or small towns, where access to education, culture, language classes and society is difficult. Refugees living in the camps face lots of discrimination, the staff in the camps have faced countless legal complaints of discrimination, violence, racism and the facilities are often under scrutiny due to overpopulation, damages, improper living conditions… it is not an easy place to live and sometimes one could think such camps have certain traces of the camps in 1942.

How has Eastern Germany changed since the recent election results?

I left Germany at the end of 2023 after finishing this project on white supremacy in Thuringen. One of the reasons leading to my decision was noticing that the rise of the AFD wasn’t particular to one region or town in the East, but rather an expanding reality that gained power and fuel with time. It made me feel that there was no place for me to really feel at home, and it also made me feel drained and exhausted. I didn’t want to face such structures anymore.

Racism does not just come from the AfD. How are refugees and BIPoc people in Eastern Germany affected by structural racism?

Racism is a structural matter in Germany. Structural means that it is a logic embedded in society through policies, bureaucracy, ideology, education, etc. In the educational system, for example, discrimination occurs based on assumptions about the capacity and ability that children have to attend university. According to research by the Open Society Justice Initiative: “Based on the testimonies of teachers, including majority German teachers, German language skills and religious instruction in school are often used as a proxy to segregate migrant children into separate classes and enable school officials to lure native German parents with ‘German language Guarantee classes.’ A recommendation for higher education in the case of students from ‘migration background’ will often be put in doubt against the premise: ‘The child comes from a family not invested in education’—a peculiar observation in a meritocracy”.

In my experience as a masters student and teacher for the Bauhaus University, I faced structural racism that had to do with language access and methodologies for my work. I did a program for media art and design that was offered in English; nonetheless, only a few of the classes for my program were taught in English, and when we demanded solutions, the administration decided to close the program without giving any answer to the students that were already taking classes. As a teacher I was confronted with administrators that were reluctant to help me as I did not speak German with them, and even when I was offered a contract for a teaching position, my visa took three months to be issued, while the staff from the migration office were extremely unhelpful and misleading. I felt that I had to beg for help, the whole process wore me out. Experiences like the ones described above lived by children in the school or by me in university have in common access to language, our migration background and the general sense of discrimination. Nonetheless, this is only the tip of the iceberg and one of the faces of structural racism.

You document not just anti-Black racism in Eastern Germany but also antisemitism. What antisemitism is being experienced and where is it coming from?

Although I haven’t worked with the jewish community as much as I would like, I documented the story of a refugee a Moroccan Jewish refugee. He has repeatedly been a target of antisemitic attacks by institutional workers in Thuringen. He came to Germany seeking the status of political refugee and was transferred from Hamburg to Suhl for a short period of time. While in Suhl, he experienced discriminatory treatment from the staff at the camp that, as he describes, began only when the staff learned that he spoke Hebrew and was Jew. On one occasion the staff member told him “Your place is the Holocaust, damn Jew.” He filed a criminal complaint accompanied by Ezra, the organisation counselling the case. Ezra’s representative said that “The subsequent process was characterized by the reversal of roles between the perpetrator and the victim. A counter-complaint was filed for defamation and false accusation. The complaint against the facility manager was dismissed by the public prosecutor’s office due to insufficient suspicion. A summary penalty order and a fine were issued against the person seeking advice”. As with this complaint, many others have been dismissed by judges that don’t take them seriously. It shows you how structural racism suffuses the legal system in Germany.

Many recent anti-racist activities, such as the attempt to block the AfD party conference in Essen, have been attended largely by White activists. What are the barriers to BIPoc people – who are the main victims of racist violence – getting involved in these campaigns? Do you think that the German anti-racist movement is inclusive enough? If not, what needs to be done?

I mean, inclusive of White people? The anti-racist movement in Germany was organised by Black Germans, migrants and other diaspora groups, and the allyship of white Germans has happened with time. There are many organisations and groups led by BIPocs that work with an anti-racist agenda. From civic education, art initiatives, to legal counselling and support, BIPoc led initiatives are present and have long-standing paths working with communities all over Germany. I don’t know the organising group against the AFD conference, but I believe that we all need to become anti-racist to be able to support anti-racist causes and have inclusivity within our circles. Only knowing that racism happens is not enough to be an ally. White people need to get trained and have a lot of self-reflection time, attend workshops, listen to other voices and give space. One reading that I recommend to start this anti-racist path is How to be an Anti-Racist by Ibram X Kendi.

You are not a politician, you are a photographer. What do you think the role of photography is in countering the far right?

I think photography can amplify stories, voices and empower people. Photography shapes representation, and representation matters! Through visual stories we can put out more diverse and intersectional narratives, giving the public and the viewer alternatives to look at the world. We can challenge mainstream perspectives through visuality and counter narratives that are segregational or blind-sided; but it all depends on the photographer and their knowledge and awareness of the world. It takes some time to decolonize the gaze and a long training to learn to look in different ways. It also is so incredibly important to learn to work with communities, collaborators or subjects. Being a photographer means having a great deal of responsibility, but also power. We hold power over the subjects and it is our duty to learn to navigate that power to create more balanced relationships in our work and to honour the subjects and their stories.

Where can people view your photography and/or support your work?

People can follow my work at @margarita.v.beltran and www.margaritavbeltran.net, I am going to take this opportunity to say that I am currently selling some of my photographs from different projects to finance a trip to the VOGUE Festival in March 2025 where I will be showing my pictures as one of the selected artists. Write to me at: margarita.valdivieso@posteo.net to get more details. <3<3