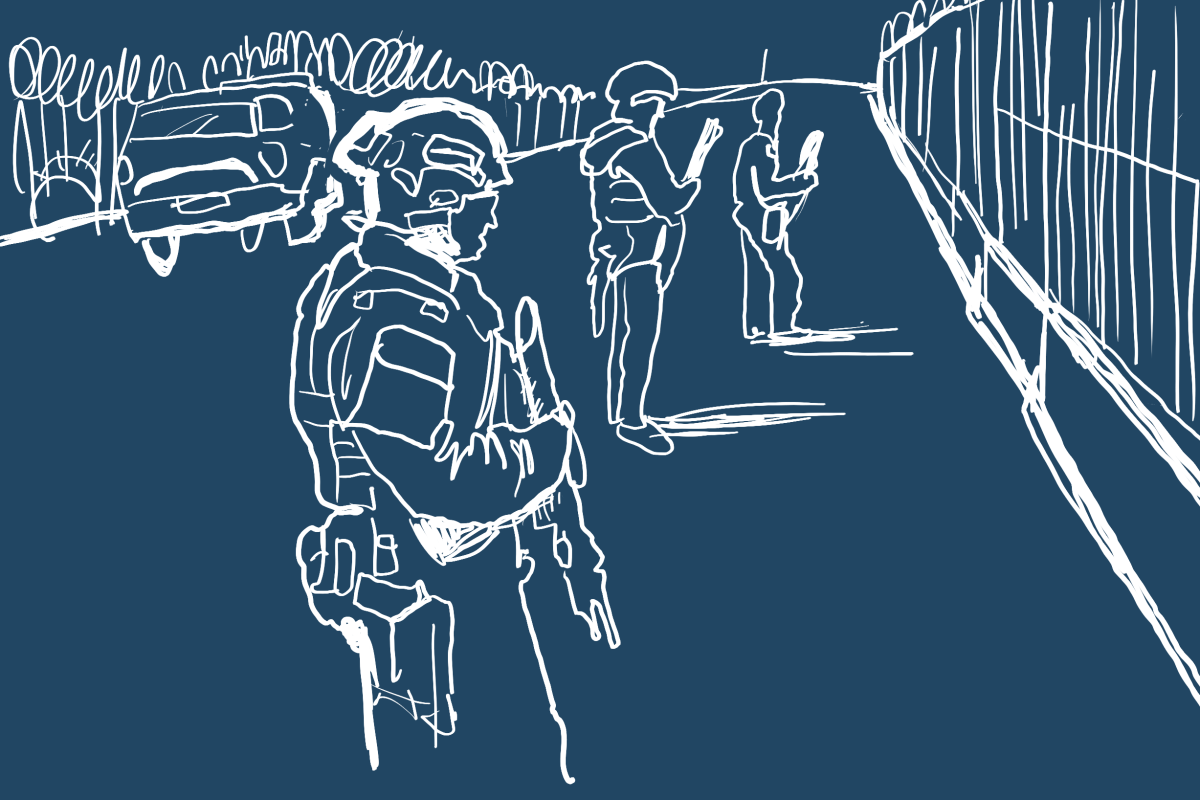

I attended a small public event organized by fellow Jews and allies, where we gathered to publicly grieve, reflect on, and learn about the ways we have been harmed by Zionism. A speech was given, names of Palestinians murdered in the ongoing genocide were read as people lay on the ground holding flowers. Suddenly, the police swarmed in on a person holding a sign that said “from the river we do see nothing like equality”. The police wanted to detain them to “check over” the sign. They refused, stating that it did not violate any laws, including the Berlin government’s ban on the statement “from the river to the sea“. Nonetheless, a number of armed officers grabbed them and violently arrested them as they stood peacefully with a sign advocating for justice.

They were charged with Volksverhetzung – one of the main German hate speech laws which criminalizes inciting hatred, and as there is no formal antisemitism law yet, this often implies inciting so called antisemitic hatred. Although this charge was later dropped in the post a few weeks later, the damage was irreversible. During the police attack on the peaceful sign holder, people stood up to verbally defend the protester, but one person made the mistake of calling a police officer an asshole. This man was violently arrested and charged with Beleidigung – a law that criminalizes insulting individuals or groups, punishable with jail time even. Yes, you read that correctly, insulting someone is a criminal offense in modern Germany. Shortly after, a young Palestinian person was also arrested and charged with Beleidigung for apparently insulting an officer in Arabic. He denies this charge completely.

Since October of 2023, I noticed these two laws seem to offer frequent justification for many other arbitrary and excessively violent arrests of activists in Germany standing against genocide and oppression in Palestine. In March 2024, an activist was charged with Volksverhetzung for wearing a jacket that said “from the river to the sea”. Under Volksverhetzung, he also had a t-shirt confiscated (it was returned after 5 months with dropped charges). Beleidigung was also the pretext used against Udi Raz as grounds to justify a recent arrest; police laughed at her kippah, so she pointed out that this was antisemitic. This was considered an insult to German Polizei, thus a potential criminal offense. These are just a few of the more publicized cases, but these are by no means the exception.

Although certain German judges have thrown out some of these charges, the brutality and oppression facing those who are in solidarity with Palestine is only getting more severe. For at least the second time in the span of a year, German police forbade all languages other than English and German at a public demonstration on the grounds that they need to check speech for Volksverhetzung (the first case I know of happened here in April, 2024 where people were forbidden to pray in Arabic during Ramadan at a legal protest camp for the same reason). As if this was only testing the waters, the German state is currently ramping up to possibly alter Volksverhetzung law to expand police power and criminalize speech further. While it wasn’t so surprising that the Beleidigung law could be used for such repressive purposes, it was only through a thorough excavation of the histories of both of these laws that I began to understand how German forces could hijack Volksverhetzung, a law seemingly created to fight discrimination and protect human rights, to become a key tool in state violence against vulnerable populations. Through this understanding, it became clear that German police employ both of these laws with their original intentions: persecution, oppression, and maintenance of domination hierarchies. Let’s take a wild ride down into the wacky worlds of German hate speech and insult law.

The modern German Volksverhetzung law, known as Article §130, is rooted in Prussia’s 1794 law code, the Allgemeines Landrecht, which banned expressions of incitement against the kingdom and against certain religious groups, along with speech that dishonored individuals, thereby also serving as the root of Beleidigung legislation (Goldberg 483). It was then written into Prussian law in 1851 as Article 100 after the 1848-49 uprisings to suppress radical leftists and maintain the power of the monarchy. The law penalized “‘whoever endangered the public peace by inciting [anreizen] hatred or contempt of members of the state against each other’ … with either a fine of twenty to two hundred Thaler or a sentence of one month to two years in prison” (Goldberg 483). The article ended up being used for “arbitrary, unjust, politically motivated prosecutions and the widespread muzzling of critical debate on public matters”(Goldberg 487). Echoing modern times, Prussian Interior Minister Otto Theodor von Manteuffel stated that this law embodied a battle between “defenders of law and order and the protectors of civilization versus terrorism.” Article 100 was reformed into Article 130 in 1871 to apparently focus the law on punishing actual violence rather than arbitrary Feindlichkeit, or hostility (Goldberg 487). Despite the so-called reform, it seemed as though matters only got worse: “Article 130 was used to repress class, ethnic, national, and political differences. Indeed, that law became so identified with government campaigns against organized labor and Social Democrats that it came to be known as the Klassenkampfparagraph” (Goldberg 481) This is the same Article 130 which governs Volksverhetzung today, albeit with some updated wording. It should be noted that shortly after creating Article 130, the government expanded the law to persecute Catholics (Goldberg 487). Amendment 130a was created to silence Catholic critics of the Protestant state during the Kulturkampf (Recall that Hitler also had some problems with the Catholics).

Unfortunately, Volksverhetzung only became more repressive as time went on. As Germany tried to “Germanize” the Poles in East Prussia, German police, prosecutors and judges used these hate speech laws to suppress Polish nationalism (Goldberg 489). Scholar Ann Goldberg recalls an outcry in 1906 by the Polish community because “popular songs, poems, picture postcards, and other visual images ranging across Polish life” had been banned and criminalized under Volksverhetzung (Goldberg 490). This is hauntingly similar to the use of Volksverhetzung today if you replace the word Polish with Palestinian. Palestinian slogans, images, posters, protests, speeches, flags, t-shirts, instagram posts and even the traditional keffiyeh have been criminalized.

Amir Ali, a Palestinian who who resides in Munich, told Al Jazeera in October of 2023:

“I was even forbidden to walk inside the city for 24 hours because I was wearing a keffiyeh. There’s a crackdown on all pro-Palestinian voices across Germany, and in my opinion, they don’t want anybody to speak up about the crimes against humanity being committed by the Israeli state.”

Scholar Ann Goldberg continues on Polish persecution under Volksverhetzung: “What rankled was not only the repression but also the biases of the authorities and the blatant partiality with which justice was meted out, sparing German racist hate speech against Poles, even when it outrightly called for violence” (Goldberg 490). This has a haunting resonance today. Take for example, cases of “from the river to the sea”; as previously established, Palestinians and those in solidarity are attacked and arrested by the police and charged with Volksverhetzung when they even hint at the phrase in regards to liberation of Palestine, but when the line is used favor of Israeli genocide and illegal annexation of Palestine, they are protected (watch this video here). And we must of course remember that the German state itself calls for, justifies, and funds the ongoing genocide in Gaza while using Article 130 to silence those who speak out.

Although Volksverhetzung law was originally designed to repress minority groups and leftists, in the 1890s, a grassroots Jewish advocacy and defense organization, the Centralverein deutscher Staatsbürger jüdischen Glaubens, attempted to repurpose the law to help protect Jews from anti-Jewish hate speech (Goldberg 483). Their attempts had some scraps of legal success, but ultimately failed, in part due to widespread anti-Jewish racism within the courts (Goldberg 494). Even at the time, some Jews were skeptical of repurposing the law to fight anti-Jewish racism, and others were openly against it (Rohrßen 149). The German left generally agreed with the latter group, and sought to abolish these laws as they saw them as a threat to basic democratic principles (Goldberg 494).

With the installation of the Third Reich, there was no hope of repurposing the law to fight for protection of vulnerable groups. Furthermore, the Nazis understood the original purpose of the law and attempted to make it even more repressive. While they never officially ratified a new version of the law, a suggested version put forth in 1933 was highly influential in how the law was to be interpreted and later re-written (Rohrßen 125). This suggestion gives us an invaluable glimpse into the fascist reinterpretation of Volksverhetzung, which still has echoes today. A Nazi jurist suggested updating the wording to focus on protecting the “peace of the people” from public discussion, printed matter or other writings which included “inflammatory” words on state affairs (Rohrßen 126). It should be understood that to Nazi Germany, and perhaps the modern German state, “people” are defined as Aryan Germans (just as, for example, America defined “all men created equal” as wealthy landowning white christian males). And we know that Hitler sent legal scholars to the US to study American apartheid and Jim Crow laws (Teter 216-217). Echoing article 130a (recall it had been used to persecute Catholics), it would be considered “especially serious” if civil servants and religious officials committed these crimes. For all “especially serious” violations of this law, deprivation of citizenship would be one possible consequence (Rohrßen 127).

This ideology is still prevalent today, although now under the guise of the war against antisemitism. Felix Klein, Federal anti-antisemitism Commissioner, while making a sweeping condemnation of many Muslims, was in favor of denial of citizenship for those who inflamed the German state through critique on Israeli war crimes and genocide. The state of Saxony-Anhalt was the first German state to require a commitment to “Israel’s right to exist” as a prerequisite for citizenship, and indeed the whole country followed suit in June 2024, requiring all applicants for citizenship to commit whole-heartedly to Israel. Invoking its namesake of upholding a [white] Christian Democracy, the CDU proposed to cut “humanitarian protection” for non-German nationals (ie deportation) and a revoking of citizenship for German dual citizens if they receive a prison sentence of one year for “crimes with anti-semitic motives.” As previously established, these “antisemitic” crimes are often prosecuted under Volksverhetzung and most often applied to racialized, peaceful protestors, Jews included (refer to my article for more cases). What’s more, the German Left: Social Democrats, the Greens and Free Democrats – also hope that “antisemitic attitudes or actions” will rule out naturalization. As antisemitism has been redefined to mean Palestinian people, Muslims, leftist Jews and critics of state violence and genocide, one must wonder how far we have come from Germany’s darkest years. As we keep exploring the history of this law, we must realize with heavy hearts, we have not come very far at all.

The Volksverhetzung law did not change much in the postwar years. Actually, in some ways, it remained exactly the same: “Although Section 130 of the German Criminal Code was subject to significant fluctuations in its interpretation, its wording had remained unchanged since the creation of the Reich Criminal Code and the provision was therefore not affected by the denazification efforts”. (Rohrßen 151) Once again, some considered abolishing the law. However, after the Holocaust, “anti-antisemitism and the Jewish cause became synonymous with democracy” (Goldberg 495) and West Germany was having trouble with its image as a post-Nazi democratic state. There were hundreds of widely reported anti-Jewish incidents, including vandalizations of cemeteries, carried out in West Germany between the end of 1959 until February 1960. West Germany needed a quick way to deal with its damaged image as a violent, racist state that failed to denazify. One quick fix was to sweep German dirt under the blue and white flag: to symbolically make amends to the Jewish people through funding the Israeli military. And another method was to attempt, at least on the surface, to protect human rights through repurposing Volksverhetzung.

Given the precedent of Jewish activists attempting to use Article 130 to fight anti-Jewish racism, Germany nobly decided to repurpose the law to ‘protect’ Jews and other non-white and/or non-Christian populations; in 1960, Germany finally updated the 3rd Reich wording of the Volksverhetzung law. The Jewish community, however, had an important warning, which had been vocalized since the 1890s (Rohrßen 149). Jewish Germans advocated that the law be used to protect all vulnerable groups, not solely Jews. The fear was that isolating Jews as a separate and privileged group would “play into the hands of antisemites” (Goldberg 497). Jewish German leadership recommended the wording “parts of the population (Teile der Bevölkerung)” rather than specifying certain races or nationalities. Although the language remains non-specific, politicians have been racing to change that: alarmingly, new CDU Chancellor Friedrich Merz recently advertised that he will greatly expand police power and control through changing Volksverhetzung law to focus on “anti-semitic perpetrators” by further criminalizing anyone who questions Israel’s “right to exist.” Furthermore, aforementioned Felix Klein, Federal Anti-Antisemitism Commissioner, has also been fighting since at least August 2023 to change the language to be specific. Germany has also singled out the Jews as a “separate and privileged group” by creating the vast array of Antisemitism Commissioners who often employ this law. Recall that no other religious or racialized group has a single commissioner for their “protection,” and only a microscopic 0.33% of the German population is Jewish. The fact that Jews can also be persecuted for “antisemitism” through this Article 130 reveals Germany’s true intentions.

As we further investigate the language used to rewrite the law in 1960 and the way this language was interpreted we might be included to crinkle our noses at the ranking fishiness, a fragrance specific to German law. The new version of Article 130 added language on penalizing attacks on “human dignity, or Menschenwürde (Goldberg 495). Although Germany had developed refined definitions of human dignity in relation to modern notions of human rights, jurists chose to define dignity in terms of military doctrine and the old Prussian honor codes it referred to: “The result was some noticeable, and sometimes distressing, limitations on the reach of German hate-speech legislation. As a leading critic of the jurisprudence of § 130 would complain twenty-five years later, the habit of looking to military law, and more generally to old-style ideas of personal honor, rather than to the great ideals of the constitution, survived” (Whitman 1341). We will shortly return to a deep investigation of German honor, but suffice it to say that this old notion of militaristic honor had nothing to do with human rights but rather with maintaining social, racial, and class hierarchies through deadly violence, and was even a fundamental ideology of the Nazi regime.

Although Article 130 eventually lost the wording on human dignity, “Hate-speech regulation was accordingly not construed to require a general climate that guaranteed minorities an equal sense of dignity; it was understood as something like a more “humane” and philosophical law of insult. This left little room for a law of hate speech that would address itself to the deeper structure of social relations-indeed, no room even for a law of hate speech that would require tavern-keepers to take down signs excluding Turks” (Whitman 1342). There was indeed a 1985 case where “no entry” signs against Turkish people were allowed under Volksverhetzung law. Apparently, if we want to further understand Volksverhetzung, we must explore the laws and philosophies which it orbits around: German insult law and German Honor.

© Jason Oberman, all rights reserved, 2025

Works Cited:

- Goldberg, Ann. “Hate Speech and Identity Politics in Germany, 1848-1914.” Central European History, vol. 48, no. 4, 2015, pp. 480–97. JSTOR

- Rohrßen, Benedikt. “Von der „Anreizung zum Klassenkampf“ zur „volksverhetzung“ (§ 130 stgb).” Juristische Zeitgeschichte, vol. 34, 12 Dec. 2009, .

- Teter, Magda. “Christian Supremacy: Reckoning with the Roots of Antisemitism and Racism”. Princeton University Press, 2023

- Whitman, James Q. “Enforcing Civility and respect: Three societies.” The Yale Law Journal, vol. 109, 2000, pp. 1279–1398

We will be publishing parts 2 and 3 of this article on theleftberlin.com soon