In Part I of this series, we explored one of Germany‘s main hate speech laws, Volksverhetzung. Now let’s take a look at its bizarre sibling, another law that regulates speech in Germany: insult law, or Beleidigung. Whereas Volksverhetzung criminalizes speech deemed to incite hatred, Beleidigung criminalizes speech deemed as insulting. We already looked at some recent cases of Beleidigung law being used to repress anti-genocide protestors; however once we evaluate some other instances where this law has been applied and excavate its history, that strange German legal funk may fill our inflamed and enraged nostrils once again.

In 1960, Klaus Walter was arrested and sentenced to 9 months prison time (he served 2) for “insulting” Chancellor Adenauer. This insult consisted of holding up a poster from a British newspaper at a demonstration, which contained a cartoon of Adenaur wiping his crocodile tears with a handkerchief covered in Swastikas, while two high level associates, Kanzleramtschef Hans Globke and Theodor Oberländer, painted NS symbols on the walls. Walter, whose father had been arrested by the Nazis due to Communist and anti-fascist leanings, was pointing out the very real fact that Oberländer had been a major Nazi figure active on the Eastern front, while Globke, Adenauer’s right hand man, was a “main architect of the legal backdrop [the Nuremberg Laws] behind which the persecution and murder of the Jews took place”.

This is not to mention the fact that Globke had also used the Bundes Nachrichten Dienst or BND (Federal Intelligence Agency) to cover up his Nazi past, that Chancellor Adenauer used the BND to illegally spy on his political opponents, and that the BND itself was run by former high level SS and Gestapo members. Beleidigung laws conveniently attempted to repress this very critical outcry, revealing West Germany was primarily concerned not with denazifying the country, but with protecting the image and honor of its ruling class.

Beleidigung law was not only used to justify state oppression, but it was also used to justify sexual assault. As sexual assault criminal law underwent serious reforms in 1997, during the proceeding period, Beleidigung law was used in at least a few sexual assault criminal cases. These occasions show us invaluable insight into the underlying ideologies of insult law.

In one sexual assault case in 1995, the violence was considered “personal need” and in another case in 1986, “permissible courtship” under Beleidigung (Whitman 1309). Underlying these cases is the German belief that women are not honor-worthy, (stemming from 19th century notions of honor we will explore in Part III of this series) and therefore cannot be “insulted” by men through sexual assault.

Although no longer used to prosecute sexual assault cases, insult law was recently used adjacent to one: a woman was sentenced to a weekend in prison for sending insults via Whatsapp to someone convicted of gang rape, while the convicted rapist avoided spending any time in prison himself.

In legal scholar James Q. Whitman’s analysis: “What the law of insult does not aim to do is establish norms that will protect traditionally inferior groups, such as women, from treatment that is likely to reinforce their sense of vulnerability, inferiority, or exclusion. It asks only whether individual women have been the targets of an open and unambiguous display of personal contempt-of, in the words of our commentary, ‘the expression of the offender’s own lack of respect for the victim’” (1310).

What a strange law indeed, you might wonder. I would respond, it only gets stranger.

As previously mentioned, the roots of modern insult law lie in the same Prussian 18th century criminal code as Volksverhetzung. Where Volksverhetzung seems to protect the honor of the state from the pesky left and non-Aryans, insult law aims to protect the honor of certain individuals.

Germany’s current, yes current, insult law, § 185 StGB, states : “The penalty for insult is imprisonment for a term not exceeding one year or a fine and, if the insult is committed publicly, in a meeting, by disseminating content (section 11 (3)) or by means of an assault, imprisonment for a term not exceeding two years or a fine.”

Whitman clarifies: “The German law of insult criminalizes words, gestures, or behavior that show Missachtung or Nichtachtung, ‘disrespect or lack of respect’ for another. [….For example] the law of insult criminalizes a gesture called ‘the bird’: the tapping of the index finger on the forehead […] It can be a criminal offense in Germany to call another person a ‘jerk,’ or even to use the informal ‘du’ [informal word for ‘you’, rather than the formal ‘Sie’]”(1297-8)

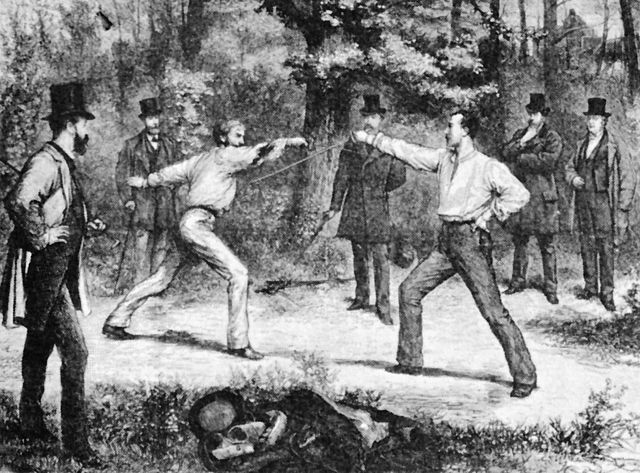

In order to further understand Germany’s law of insult, we must dig deeper into its history: a misappropriation of Roman law, which criminalized insults (an insult being defined as a severe physical assault at the time), Beleidigung developed as a way of bringing deadly and utterly petty aristocratic German duels to court to prevent murder (Whitman 1316-17). The duel was originally developed in France, also rooted in practices of medieval knights, and became popularized in Germanic states by the end of the 16th century. Although outlawed to varying degrees since at least the 17th century, the duel nevertheless survived, and under various rulers was tolerated if not outright encouraged. By the end of the 19th century, the German duel had distinguished itself in its commitment to fatality.

By that time, the duel had been extinct in Britain, and turned into a less deadly form of fencing in France, while in Germany, “the questionable but seldom questioned syllogism for satisfaction read: The greater the danger, the greater the honor; pistols are more dangerous than sabers; therefore pistols are more honorable.” ( McAleer 59) Under dueling code, there were three kinds of insults, which warranted, or rather necessitated for some, a formal challenge to death:

1.einfache Beleidigung: “constituted by impoliteness or inconsiderate behavior”,

2. cursing or name calling, including “Esel (jackass) or a Schwachkopf (imbecile)”,

3. a blow, slap, or even gauntlet in the face (McAleer 47)

There were different rules for each classification, but each one could be settled with death, and “German-language codes recommended that all third-level insults be settled with pistols” (McAleer 47-48). In Germany, being simply impolite used to be grounds for a murder.

Given the vast array of possible insults, and seeing as it was the duty of men of honor to fight unless, god-forbid, they be seen as cowards (McAleer 48), by the time of the 2nd Reich, Germany found itself with the most deadly and long-lasting dueling culture in Europe. Instead of rethinking the highly problematic German code of honor, which led to these deadly duels in the first place, Germans decided the best alternative to the duel was to formally criminalize breaches of honor, even if absurdly trite. Despite the formal implementation of insult law in the 19th century, the duel persisted with deadly force until at least WW1 and still continues in the form of the non-lethal student Mensur.

Alas, in 2000, Whitman disappointingly concluded, “to this day, the definition of the sorts of substantive insults penalized under the law of insult is, to a startling extent, still drawn directly from old dueling norms.” (Whitman, 1334)

Unfortunately but unsurprisingly, the Nazis played a critical role in shaping insult law. As we saw with Volksverhetzung, where Nazis democratized protection of the “peace of the [Aryan] people” rather than specific classes, Nazis democratized Beleidigung to protect the honor, or as Whitman puts “the privilege of arrogance” of all people in the Aryan race —not just the aristocrats and upper class military officers protected by insult law in the 19th and early 20th centuries. However, insult law was not enough to restore Aryan honor, and Nazis even briefly reintroduced the duel in 1936. The Nazis also created precedent for “group insult”: the idea that a whole group could be insulted. This was used to prosecute a man overheard calling the SA and SS “scum” in a barbershop (Whitman 1328).

In the final analysis, insult law was primarily concerned with “compelling low-status persons to show respect to high-status ones.” (Whitman 1314), and given its modern usage, I argue it still is. Even though the Nazi “group insult” laws have been partially repurposed to protect Jewish people in certain circumstances, they seem to completely fail to protect, and perhaps even oppress, other non-Aryans, women (Whitman 1310) and non-Zionist Jews as well.

In the best case, insult law can allow oppressed peoples to bring insulters to court on an individual basis. However, in the most realistic evaluation, insult law continues to serve the white Christian ruling class.

Ultimately, in the brittle and wise words of Whitman: “All of this will inevitably lead Americans [or any human being, I would add] to wonder whether such a body of law can survive in a modern democratic society. Nevertheless, it survives.” (1312)

After our analysis of both Beleidigung and Volksverhetzung laws, I can only pose the question, was Germany ever really a democratic society?

Next up, in Part III, we’ll explore German Honor – the undercurrent of these two laws and perhaps contemporary German society itself.

© Jason Oberman, all rights reserved, 2025

Works Cited

- McAleer, Kevin. Dueling: The Cult of Honor in Fin-De-Siecle Germany. Princeton University Press, 1994.

- Whitman, James Q. “Enforcing Civility and respect: Three societies.” The Yale Law Journal, vol. 109, 2000, pp. 1279–1398

You can read part 1 of this article here. We plan to publish Part 3 on theleftberlin.com on Wednesday, April 2nd