Great literature, Ezra Pound wrote, is news that stays news. The Great Gatsby illustrates this well. Let’s start with one clear example, before we get to all the rest.

Early on in the novel Tom Buchanan identifies himself to us as a racist bigot when he blurts out, ‘Civilization has gone to pieces …Have you read The rise of the coloured empires by this man Goddard?… Well, it’s a fine book…The idea is if we don’t look out the white race will be—will be utterly submerged…It’s up to us, who are the dominant race, to watch out or these other races will have control of things…we’ve produced all the things that go to make civilization—oh, science and art, and all that. Do you see?’ This sentiment was printed in a novel published in 1925.

And now we have two leading figures from Reform UK, a far-right party, in 2025; James McMurdock, who said that ‘the murder rate’ was ‘better in medieval England than Africa today’, That is how civilised our society is, that is how gentle, even handed, fair and good we are as a people.

‘We take it so much for granted that we think the rest of the world is like that,’ McMurdock continued, ‘We already know what needs fixing because it didn’t used to be’.

Another speaker, Max Harrison, membership coordinator at Reform UK’s head office, spun a narrative of decline, ‘This is about our community, our culture, our history, our heritage, our traditions, our Christianity and our values. We are in societal decline. Our communities are broken. Our children go to schools and are fed poison. Our streets are lawless and everything about our lives is getting increasingly worse.’

News that stays news.

Since 1925 many people have been beguiled and dazzled by the shiny surfaces of the ‘Jazz Age’ and Fitzgerald’s depiction of it. One of those surfaces is the way in which the novel is attracted by one of the great myths of the USA. That it is the place where dreams can be fulfilled, where James Gatz, poor boy from the Midwest can become Jay Gatsby; possessor of vast wealth and a vision of lost love regained.

Except, of course, that the glitter of those surfaces just conceals the tawdriness beneath. Because, with one exception, this novel is populated by characters who are false. They are liars, thieves, gangsters, adulterers, racists, antisemites, cheats, killers, bad drivers. One of the triumphs of the novel lies in the way it ruthlessly, almost savagely rips away the facades behind which corruption and violence simmer.

Baseball occupies a place in US culture in which a chimerical belief in fair play and honesty, mixed with a hint of heroism, function as a haven of sorts from the unfairness and the cheating beyond the stadium. It’s nonsense, of course. So it is unsurprising that in this book we meet the gangster who ‘fixed the World Series.’ Gatsby, we come to understand (and then perhaps forget), has raised his mansion with cash from proximity to extractive capitalism and gangsterism. Raised the mansion to charm back his lost love. And when he has retrieved her and shows his treasures, she responds not with words of love but repeated admiration for his closet full of beautiful shirts. The book’s litany of houses, apartments, cars, libraries in which the owner has had the ‘good taste’ to not cut the pages of the volumes on the shelves, remind us repeatedly that the cruel wonder of commodities is that they replace human connection with relationships to objects.

Through the voice of Nick Carraway (incidentally, magnificently reproduced by Tim Robbins in an audiobook) these people and the fabrics of their existences are exposed. He demolishes the vulgar, violent racist Tom Buchanan. For all their attractiveness, he recognises Daisy Buchanan and Jordan Baker for the hollow ciphers that they are. He situates the gangster Meyer Wolfsheim with the observation that he wears cufflinks made from teeth. He is forensic in his clarity of vision.

But. But we would be very naïve readers to believe everything (or perhaps even anything) Nick tells us. He asserts his honesty so much that it seems that he doth protest too much. He is, along with the others, a racist and a misogynist. He asserts his heterosexuality but in a fleeting lacuna within the narrative seems to have had sex with another man. More, much more importantly, he works in that great con game that would four years later shatter the world economy and plunge millions in poverty and desperation. Nick is a bond salesman. Perhaps his one saving grace is his rejection of an offer to engage in some insider trading.

News that stays news.

It all shatters and disintegrates. It is brought low by bad driving, murder, cowardice and fatally misplaced loyalty. At the heart of that is the wrecked life of George Wilson. Eking out a living on the edge of the ‘valley of ashes’, emotionally and often physically abandoned, the book hovers at the site of his grief for his dead wife even as the other characters rush away. Even that still moment, though, is cast away when George murders the wrong person and then kills himself.

At the conclusion of the book Nick Carraway is alone with two insights.

First, is that perhaps the only way to redemption is to return to that passed moment before the Dutch sailors arrived at New York in an example of the magnificent prose of the novel—‘For a transitory enchanted moment man must have held his breath in the presence of this continent, compelled into an aesthetic contemplation he neither understood nor desired, face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder.’

Nick then moves to the recognition that this is an impossibility, no matter how much we wish for that utopian return to a time before all that the USA had become by 1925—all that the USA has become by 2025. Gatsby’s redeeming feature, for Nick at the end, is his attempt to grasp that past, even as it drifts away, even as its futility becomes more apparent.

News that stays news.

Second, Nick comes to a clear understanding of Tom and Daisy as they move to protect their status and wealth against any intrusion. He has stood in the dark, watching them through a lit window and comes to this conclusion:

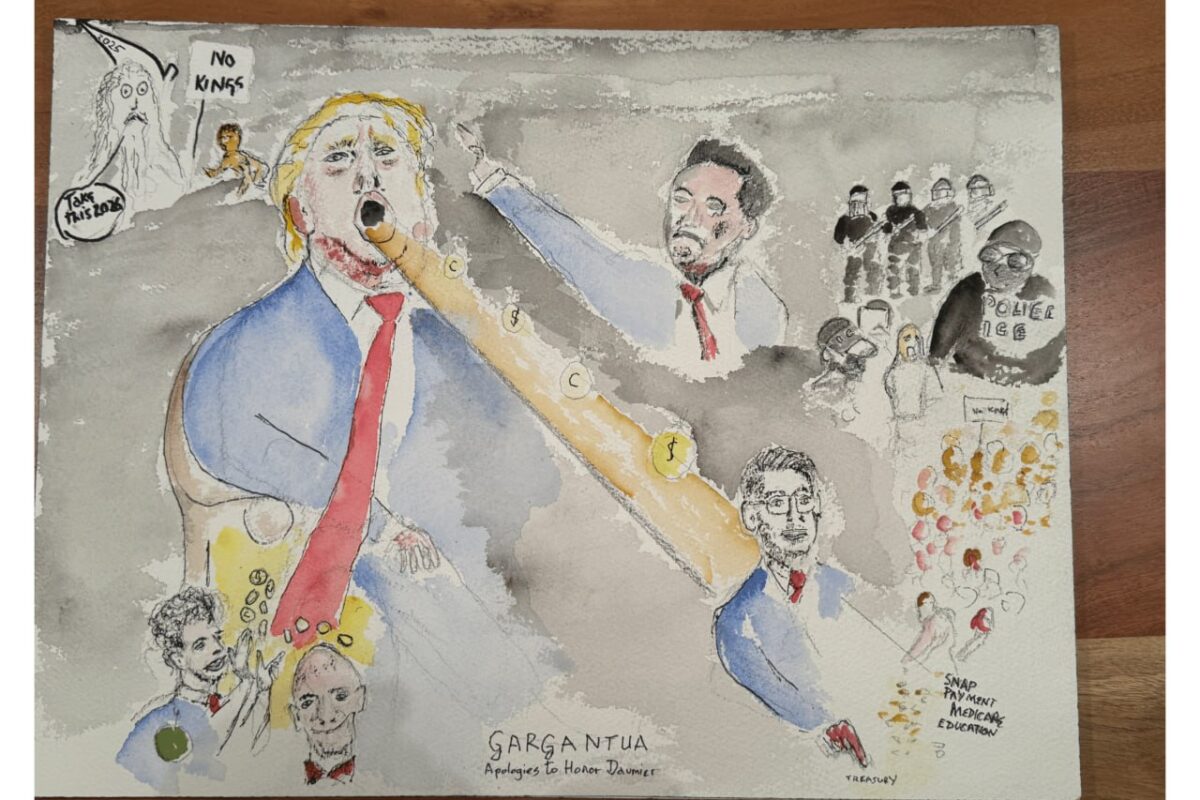

‘They were careless people, Tom and Daisy—they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness, or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made.’

Time for us to refuse to clean up their messes any longer.