At Europe’s south-eastern external border lies Bulgaria: a country which has been in political crisis for years and just saw major Gen Z-led protests, which caused the collapse of its government. But it also has a decisive role in upholding Europe’s border fortress. Bulgaria is often the first European Union country on the so-called Balkan migration route. People who come from Syria, Kurdistan, Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran, or Morocco will likely enter the EU from Turkey into Bulgaria.

Many human rights violations have been published since 2015, directly asking EU bodies to increase pressure against Bulgaria’s illegal practices at their southern border with Turkey. Instead, Bulgaria became a member of the border-free Schengen zone in 2025. The EU Commission could have used the accession process to force Bulgaria to comply with human rights standards. A missed chance. Rather, since Bulgaria joined the Schengen zone, reported human rights violations have continued as multiple testimonies indicate.

Border violence

The Balkan route has been a topic of discussion for the past ten years. Bulgaria started building a 230km barbed-wire fence at its southern border in 2017. To cross this border, people on the move walk for days, crossing rivers and forests with temperatures dropping to minus 10 degrees Celsius. Making it across does not guarantee people the right to seek asylum, although this is enshrined in the 1951 Geneva Convention. Every year, tens of thousands of people are illegally pushed back at the Bulgarian border. In 2023, 175.000 cases of illegal pushbacks were identified, and at least 70 people died due to exhaustion, dehydration or hypothermia.

People on the move report illegal and violent pushbacks directly at the border to Turkey, as well as hundreds of kilometres away from the border back to Turkey. Some people describe being taken to the police station for 1–3 days before being forced into police trucks back to the border, without a chance to ask for asylum, a clear violation of international law. During pushbacks, people are beaten with fists and sticks. Police dogs are used to catch and attack people, phones are destroyed, people are strip-searched, and valuables and clothing are stolen, leaving some only in underwear without shoes in freezing temperatures. Racist smears, such as calling people read as from the so-called Middle East or Northern Africa “Taliban”, have been published by Human Rights Watch and No Name Kitchen, two organisations, among others, taking testimonies of people on the move. Some people have been shot at.

After years of reporting by activists, non-governmental organisations and investigative journalists, EU-bodies are quite aware of the situation at the Bulgarian-Turkish border. But Bulgaria plays a key role in the border security enforcement of the EU. Due to its crucial geographical position as the first EU country on the Balkan migration route (with Greece), the EU directly benefits from these illegal border practices.

Supported by Frontex

Frontex, the EU’s border agency, also operates at Bulgaria’s border to Turkey in cooperation with national authorities. They support border surveillance through patrolling, thermo-vision equipment and police dogs to detect “irregular migration”. The EU tripled the presence of Frontex in 2024, in preparation for Bulgaria joining Schengen. In their own words, their operations focus on ensuring fundamental rights and human dignity.

Activists on the ground call out Frontex for their role in the region regularly. The presence of Frontex does not lead to more safety. Rather, officers are directly involved in border violence. Internal reports of Frontex have shown that their officers have taken part in illegal pushbacks.

In 2024, three boys died at the border. While people on the move die regularly due to neglect or actions by authorities, this case got more publicity. Human rights groups had the location of the minors and could have possibly prevented their deaths if they had not been actively hindered in their rescue actions by Frontex and national authorities for days. Frontex published a report blaming Bulgarian authorities for these deaths. But local activists and organisations have called out Frontex for their role in interfering with rescue actions of activists on the ground.

Beyond the border region

Europe also benefits from the harsh system placed on people on the move once they have made it into Bulgaria. People on the move are usually taken to closed camp facilities to start their asylum process. Lyubimets detention centre in the south of Bulgaria is one of those camps. It was built in 2011 as part of Bulgaria’s efforts to prepare for the Schengen accession process. Lyubimets has 5-meter-high walls with barbed wire fences, guards patrolling, and visiting hours limited to two hours twice a week. It is a closed facility; people are never allowed to leave except when their time is up, or they manage to pay for a lawyer to appeal their stay. People are regularly detained for 18 months without trial. There is also the infamous Busmantsi detention centre, located on the outskirts of Sofia. It is known for its inhumane conditions and arbitrary detention practices. It has operated since 2006 and is also funded by the European Union. These places do not feel like a prison by accident. They are designed to do so.

In Lyubimets and Busmantsi, as well as in other facilities, people on the move regularly report unsanitary conditions, insufficient nutrition and heating, violence by police officers, unannounced deportations, and violations of their rights to receive visitors and see lawyers as well as access to privacy and fresh air. Infestations of bedbugs, lice, cockroaches and rats are persistent across all facilities. Medical help is rudimentary, and psychological assistance is not provided.

Even visits by European Union committees have reported physical violence and verbal abuse by guards and inhumane living conditions. But the EU continues to finance this system of neglect. Between 2023 and 2024 alone, the European Union has provided millions of euros each year to Bulgaria for its migration policies: €45 million (2023), €141 million to Bulgaria and five other EU member states (2023), €85 million (2024) to Bulgaria and Romania, and another €20 Million (2024) to Bulgaria alone. Despite the financial support, all national detention centres are deteriorating. The capacity has decreased from 5,160 places to 3,225 in 2024 due to premises identified as unfit for living.

The lie of voluntary return

That Bulgaria is reducing the number of positive decisions taken on asylum requests since 2023 goes hand in hand with the overall strategy of isolation and “fortressing” of the EU. For Syrians, this meant a drop of asylum approvals from 90% to 18% in 2024, even before the fall of the Assad regime. At the same time, Bulgaria has increased deportations. People who sit in detention facilities are deported quietly and without warning, not providing them the chance to appeal.

If no deportation agreements with countries exist, pressure is increasing to sign a “voluntary” return agreement. Bulgaria launched a new Assisted Voluntary Return and Reintegration (AVRR) Programme in 2024. Three-quarters of the funding comes from the European Commission.

Voluntary returns are defined by the United Nations refugee agency as based on a “free and informed choice”. But since the start of the programme, people have reported being forced to sign. The consequence of not signing is often (prolonged) prison time, leaving people no real choice but to agree to their own deportation. Some people have reported not receiving translations when forced to sign documents, only to later find out they agreed to a “voluntary return”.

These violent and degrading practices are intended to lead to despair. The hope for a more peaceful future is intentionally being destroyed. And it is working. More and more people are signing “voluntary return” papers. The EU is once again not upholding its own standards.

If public pressure does not increase, these practices will become even more systematised. Red lines are crossed without much happening— three minors die, and business at the border continues as usual. Rather than any consequences, EU countries, above all Germany, are more frequently deporting people back to Bulgaria based on the accelerated Dublin procedure, notwithstanding family and personal ties in Germany, or the inhumane conditions people on the move face on the ground.

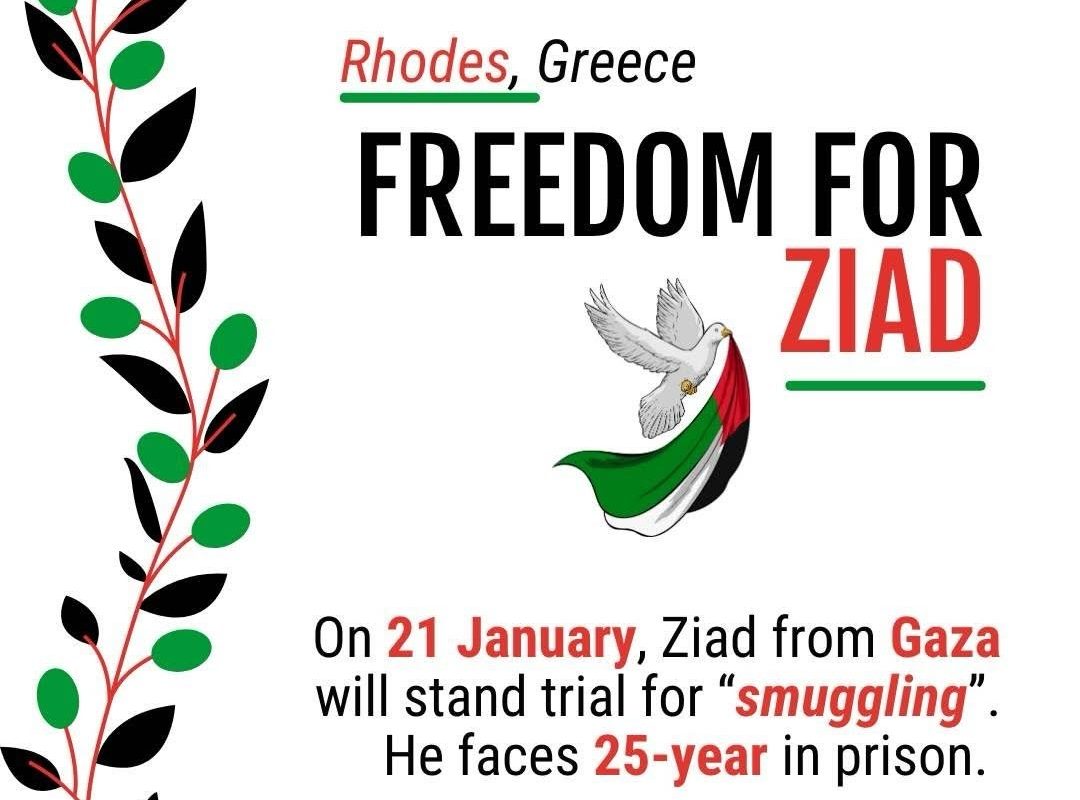

What is needed is what human rights organisations have been calling for for years: safe and legal ways to seek protection in Europe, an end of violent pushbacks, abuses and arbitrary detention, more humane conditions in camps, independent observers in the border region to ensure compliance with international law, more transparency and an end to the criminalisation of people on the move and activists on the ground.