Under the banner of “labor shortages” and “productivity”, political voices are now flirting with the idea of restricting the legal right to part-time work. Not banning it outright, they say; just limiting it. Reframing it. Reserving it for those who can justify their need for less time, less exhaustion, less surrender. And this debate is not about hours. It is about power.

For decades, the right to reduce working hours has been one of the quiet achievements of modern labor law: an acknowledgment that human beings are not infinitely elastic, that life does not begin and end at the workplace, that dignity includes control over one’s time. To roll this back is not reform. It is regression dressed up as responsibility.

The argument goes like this: Germany needs more labor. People must work more. Those who choose part-time work for “lifestyle reasons” are portrayed as indulgent, unserious, even morally suspect. Leisure becomes laziness. Balance becomes betrayal. But this framing collapses under the lightest scrutiny.

People do not flee full-time work because they have grown soft. They do so because full-time work, as it exists today, is often incompatible with a livable life. Childcare is scarce or unaffordable. Elder care is chronically underfunded. Many jobs demand constant availability, emotional labor, unpaid overtime, and a level of intensity that leaves little room for anything else — including health.

Calling this a “choice” is convenient. It absolves the system.

Restricting part-time work does not create more care infrastructure. It does not raise wages. It does not shorten commutes or reduce burnout. It simply transfers the cost of systemic failure onto individual bodies disproportionately onto women, who make up the majority of part-time workers, and who already shoulder most unpaid care labor.

This is not an accident. It is a pattern.

Whenever economies face strain, the solution proposed is rarely to rethink how work is organized or how wealth is distributed. Instead, the reflex is discipline: longer hours, fewer rights, tighter control. Work is moralized. Exhaustion is normalized. And those who resist are scolded for lacking commitment.

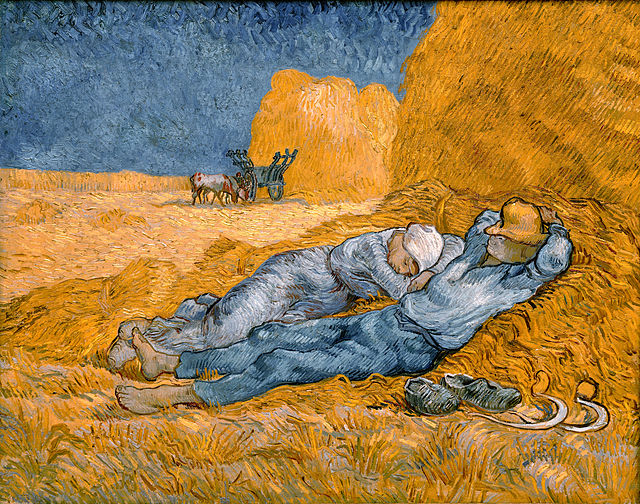

Yet history tells a different story. Every gain workers now take for granted (the weekend, the eight-hour day, paid leave) was once condemned as dangerous indulgence. Each was resisted with the same warning: the economy cannot afford this. Somehow, it always survived.

What is new today is the audacity of reversing progress in the name of modernity.

Germany is not suffering from a shortage of work. It is suffering from a shortage of humane work. Productivity has risen for decades, but the benefits have not translated into more time, more security, or more freedom for workers. Instead, we are told to give more of ourselves to maintain a system that gives less back and this reveals the deeper ideological fault line.

Is work a means to live — or is life merely fuel for work?

Those pushing to curb part-time rights seem to believe the latter. In their worldview, time not sold to the labor market is time wasted. Autonomy is tolerated only when it does not interfere with output. Freedom is acceptable only after productivity quotas are met.

This is not economic realism. It is moral authoritarianism.

A society confident in itself does not coerce people into longer hours. It makes work worth returning to. It invests in care, flexibility, and fair pay. It understands that people who control their time are not weaker workers, but stronger citizens. If the CDU truly wants higher labor participation, the path is obvious and inconvenient. Build childcare. Fund elder care. Reduce full-time hours without reducing pay. Allow people to work more by needing less. Anything else is not reform. It is a command.

The right to part-time work is not a luxury for the lazy. It is a safeguard against a future where economic necessity consumes every waking hour. To dismantle it is to say, quietly but clearly, that human life must once again bend to the demands of the market.

And that is a line worth refusing to cross.

Because when a society solves its problems by demanding more life from its people, it is not running out of workers. It is running out of imagination.