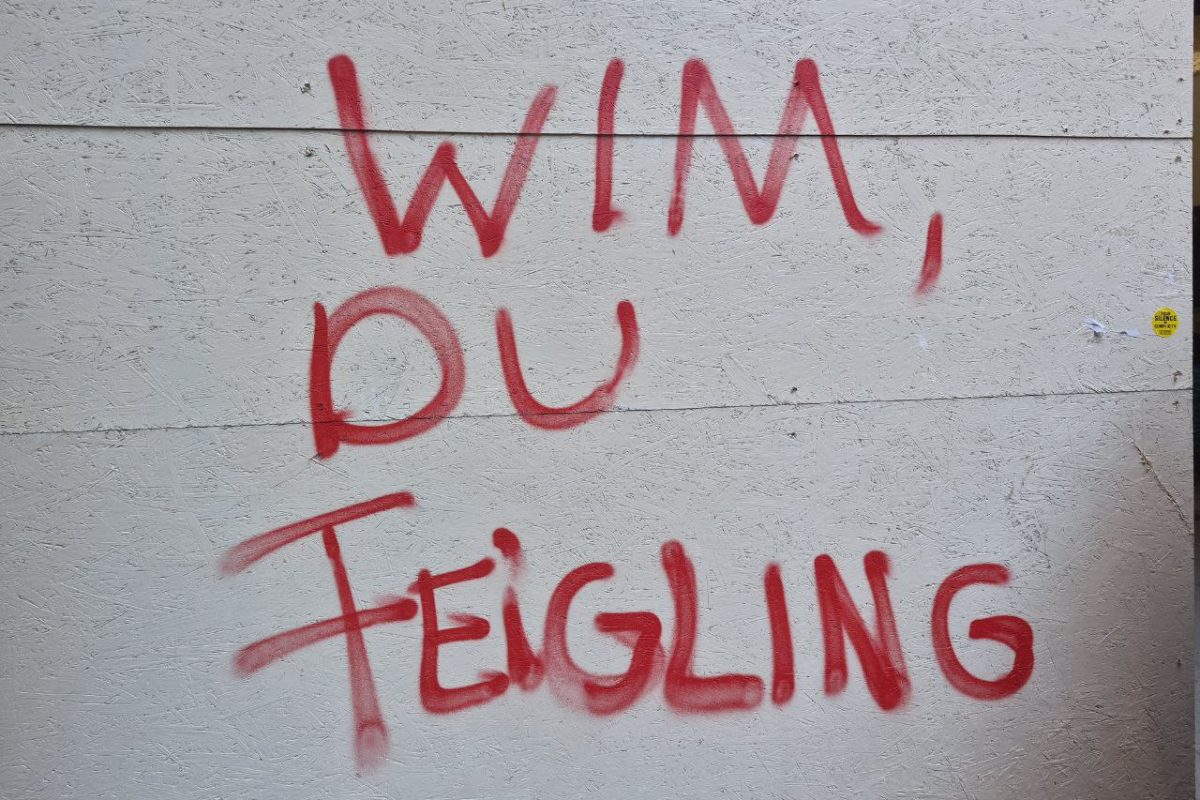

Most people will know by now that Wim Wenders, jury president of this year’s Berlinale, recently said “We have to stay out of politics.” He continued: “movies can change the world, but not in a political way.” At the same press conference, Ewa Puszczyńska, producer of The Zone of Interest, said: “we cannot be responsible for what [an audience’s] decision would be to support Israel or the decision to support Palestine. There are many other wars where genocide is committed, and we do not talk about that.”

In response, Arundhati Roy, whose film In Which Annie Gives it Those Ones is due to be screened as part of the Berlinale, announced that she would no longer be coming to Berlin. Roy made her own statement, saying: “To hear them say that art should not be political is jaw-dropping. It is a way of shutting down a conversation about a crime against humanity even as it unfolds before us in real time—when artists, writers and film makers should be doing everything in their power to stop it.”

As a best-selling author, scriptwriter, and anti-capitalist theoretician, Roy had every right to call out both Wenders and the Berlinale for their lack of solidarity with Palestinians who are still suffering a genocide. Yet there is some uncertainty about what Wenders actually said, not least because of the incoherence of his original statement.

In this article I want to look at what Wenders did say and why he said it. I will go on to argue that this is just the latest in a long series of instances in which the Berlinale, and its representatives, have stood in the way of the Palestinians’ fight for liberation.

What did Wenders say? And what didn’t he say?

It would be easy to dismiss Wenders’ statement as the liberal hypocrisy of a man who has spent too much time with Bono. However, I do not believe that Wenders was arguing that no art is political—an untenable position that doesn’t hold up to any serious scrutiny.

In the same speech, he said: “No movie has really changed any politician’s idea. But we can change the idea people have of how they should live,” and “There’s a big discrepancy on this planet between people who want to live their lives and governments who have other ideas.” There is a case to be made that Wenders was not arguing that cinema should be unpolitical, but that the balance of power means that politicians will ignore films, which should, instead, try to address “people”.

Nonetheless, I do believe that Wenders still thinks that Great Art occupies a sacred place outside social relations. Or, as he says, “We have to stay out of politics because if we make movies that are dedicatedly political, we enter the field of politics. But we are the counterweight of politics, we are the opposite of politics.”

In this context, it is worth looking at this year’s nominations for Best Picture Oscar—no guarantee of artistic quality, but nonetheless a sign of current trends. The nominations include Sinners, a film that addresses the legacy of racism in the US South, One Battle After Another, which features state detention centres, clandestine right-wing organisations, and former and future revolutionaries. Bugonia is about conspiracy theorists, and The Secret Agent looks at 1970s Brazil under the dictatorship.

Or we could look at the homepage of the 2026 Berlinale, where you can read: “The exciting thing about this year’s edition—probably the most political in a long time—is the diverse range of different cinematic forms used to set out concrete themes that hurt, such as enduring colonialism and the structural repression of Indigenous populations, violence against women, systems of corruption, social injustices.”

The Berlinale’s page about the Teddy awards promises: “Films that resist the mainstream, challenge racist structures and genre conventions and explore queer resistance alongside gender and body politics form a vital core of this year’s programme. This discussion considers the significance of such works in relation to the cultural and political moment we currently inhabit and asks whether, and in what ways, these films might serve a broader purpose beyond the screen.”

You can argue about both the political and artistic quality of some of these films, but we are not in a period in which either Hollywood or the Berlinale are staying out of politics.

Can art be unpolitical?

Before I move on to what I think is going on here, I’d like to address the issue implicitly raised by Wenders’s statement—the idea that while some films may have political content, the best art remains politically neutral (whatever that means). Perhaps it is worth mentioning here that only 9 months ago, Wenders himself made a film for the German Foreign Office.

Wenders was not the only person arguing for “unpolitical” art. After the scandal broke, self-regarding German actor Lars Eidinger said that he was only at the Berlinale for the cinema, adding: “Sometimes you come to the Berlinale to watch the films you’ve made yourself.” This may well describe Eidinger’s viewing habits, but he does not speak for all of us.

It is difficult to imagine any film that is not political, indirectly at least. All films are set in a certain era and in one way or another reproduce the contradictions of class, race, and gender in the society which they are describing. Clearly some films are explicitly political, but I would go further. Because they are the products of social relations, all films are political.

Even a film that uses exclusively middle class white male actors is doing this for political reasons. A Merchant Ivory film in which every single character is white and well off is making a political statement about what it considers to be important every bit as much as any film by Ken Loach or Gillo Pontecorvo. As John Berger said in Ways of Seeing, works of art are defined just as much by what they omit than what we can see.

To back up this argument, I would like to quote from the 1991 book The Logic of Images. You can find this quote on the goodreads page: “Every film is political. Most political of all are those that pretend not to be: “entertainment” movies. They are the most political films there are because they dismiss the possibility of change. In every frame they tell you everything’s fine the way it is. They are a continual advertisement for things as they are.”

Great stuff. And who wrote The Logic of Images again? Oh yes, it was Wim Wenders.

It’s all about Palestine

So, what was Wenders really trying to say? A little context is useful here. Wenders’s statement was a direct response to a question by Tilo Jung from the Jung & Naiv podcast. Tilo asked: “The Berlinale as an institution has famously shown solidarity with people in Iran and Ukraine, but never with Palestine, even today. In light of the German government’s support of the genocide in Gaza and its role as the main funder of the Berlinale, do you as a member of the jury…”

Viewers of the Berlinale livestream never got the chance to see Tilo finish his question (“Do you as a member of the jury support this selective treatment of human rights?”). Coverage was interrupted, with the Berlinale organisers announcing “technical problems”. Whether they were lying or not is a secondary point. Wenders was not saying that the Berlinale cannot discuss politics. He was saying that they can’t discuss Palestine.

Wenders, like many German artists, has a history of staying silent on Palestine. Last year, Françoise Vergès published an essay in which she said of Wenders: “His is a Eurocentric history, as if this history ended in that European ‘centre’, with not a single word about the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He speaks of Ukraine but not of Gaza, nor Sudan, Congo, Kashmir or any other place in the world that does not belong to the white West.”

Abbas Fahdel was part of the 2024 Berlinale documentary jury that awarded a prize to No Other Land. He recently argued: “Since then, it has effectively made it impossible for films openly committed to the Palestinian cause or critical of Israeli government policy to be present. Wenders’s position today, under the cover of supposed artistic neutrality, seems to confirm and legitimize that shift.”

The Berlinale was always political

The Berlinale has a long history of political statements. At the 1991 festival, Iranian director Jafar Panahi was supposed to be one of the jurors. The Iranian government refused to let him leave the country. The Berlinale website still proudly reports its response: ”The Berlinale sections screened five of his films in 2011 as a sign of solidarity.” When the jury announced its decisions, Panahi’s chair was symbolically left empty.

The 2023 Berlinale issued a statement Solidarity with Ukraine and Iran, in which it announced: “The film selection and various events—in part with cooperation partners—will focus on Iran and Ukraine”. All companies and media outlets with ties to Iran or Russia were banned. The same year, the festival was opened with a 10 minute speech by Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy. I do not recall any objection from people like Wenders that this was politicising an event that had to stay out of politics.

In 2024, Wim Wenders proudly told the German press that: “The Berlinale has always been the most political of the big festivals”, and “I like the Berlinale because it always opens its mouth and takes a stance”. On that occasion he was commenting on the festival’s decision to uninvite five AfD politicians. Note that even in this case, it was not that the festival refused to invite a bunch of Nazis. It invited them, and was then forced by public outrage to change its mind.

The IMDb description of No Good Men, the opening film at this year’s Berlinale, describes it as a “lumpy mix of workplace observation, anti-patriarchal social realism, spiraling alarm over the return of an oppressive regime”. Meanwhile, festival director Tricia Tuttle boasted to Deutsche Welle that the festival is “not afraid of championing and backing very political films—films that might create difficult talking points”, adding that “every kind of cinema is political in some ways”.

Time to boycott the Berlinale?

In 2024, Strike Germany, an organisation representing more than 500 global artists, filmmakers, writers and culture workers called for no more collaboration with German-funded cultural institutions, which—they said—were carrying out “McCarthyist policies that suppress freedom of expression, specifically expressions of solidarity with Palestine”. This explicitly included the Berlinale.

In 2026, Strike Germany issued a new statement, saying: “STRIKE @berlinale is not over. With continued lack of genuine response from Tuttle and the Berlinale team, it’s clear that in 2026 Berlinale remains committed to its irrelevance for film workers who oppose genocide. Berlinale must understand that if it does not use its remaining power as a cultural force in the capital, then it does not deserve our participation.”

I’m not fully convinced by the arguments to boycott the Berlinale in 2026. For a boycott campaign to be effective, it needs to be a mass action. Otherwise it risks being just individual virtue signalling. This year—unlike in 2025—the international BDS campaign has not targeted the Berlinale. But if anything has shown the need for a political reaction to the festival’s whitewashing of Gaza, it is Wenders’ badly worded and reactionary speech.

This year, the Palinale Film Festival showed that there are plenty of film offers outside the Berlinale. Palestinian activist Majed Abusalama, who will be speaking at the Palinale on February 18th, posted on facebook: “It is no longer enough to simply condemn the Berlinale each year. The community must begin building alternative cultural platforms that reject complicity and center decolonial, unapologetic representation.”

Recent films like The Voice of Hind Rajab, All That’s Left of You, and Coexistence: My Ass! have been prepared to take on different aspects of the Israel/Palestine struggle whether the Berlinale wants them or not. As a movement, we need to decide whether to kick the Berlinale into touch, or if we think it can be saved from itself. Either way, there are plenty of viable alternatives.