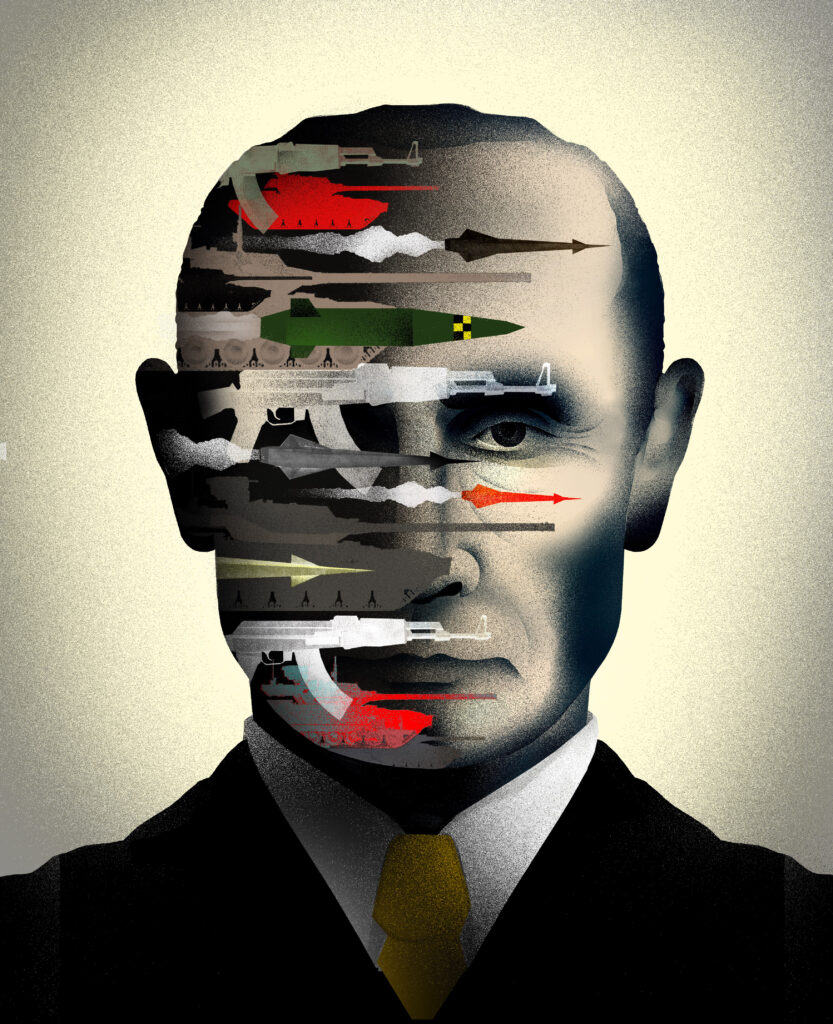

If a picture speaks more than a thousand words, there are few people who have challenged people more than Brian Stauffer and his 300 images. Both in top US news magazines like ‘Time’ and ‘The New Yorker’, and in Germany’s ‘Der Spiegel’, Stauffer has illustrated concepts behind the news in his colourful way for over 30 years. His unique style captured what many people felt and put into colour the most vile right-wing populists of our age. In particular, Russian President Vladimir Putin and US ex-president Donald Trump. A strong critic of war and police violence who never ceases to point out abuse of authority, the Arizona-born artist’s work is on display at the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation until August.

In Berlin, Stauffer spoke of his ‘frustration’ over far right narratives that had taken over his native United States since the arrival of Trump. Stauffer could not even believe such a narrative was possible: “In 2015, the year before the 2016 election, I was in Bogota, doing a series of workshops with students there and they were saying, ‘How can this be how can this be?’ I kept telling them, don’t worry, it’ll never happen. Cooler heads, smarter minds, will prevail – this guy will be found out. And I was just proven wrong in every possible way. So could it happen again? Yeah. It could. And will we survive it? I think so.”

He explained how, the USA was polarized by political forces beyond any mainstream control. This allows Trump followers to now attempt suppressing all critique of history.

“Somehow, someone made a false equivalence of freedom of speech with intolerance and bigotry and then to take it even one step further, used it to inhibit others rights as an individual. It’s just a very slippery slope. When you’re surrounded by figures that have abandon the restraint of shame, the potential is unlimited.”

Trump’s appointments at the Supreme Court continue to strengthen this change of perspective across the country, even as the divisions fester. Even the Black Lives Matter protests were politicized, to the point that the far right narrative considered any discussion of the past as somehow unpatriotic.

“Currently, there is a trend to want to not look back on the history of the genocide of Native Americans and the 400 years of slavery and that by somehow looking back, we are dishonouring all that has been done before,” says Stauffer. “And it’s that kind of hyper-simplicity that plagues the public discourse right now between the two very angry sides in our country. And as angry as I am about it, and as frustrating as it is, the rage itself has to be tempered because very quickly the messages become hyperbole and overstatements, and they become a different form of lies.

“What makes it particularly upsetting is that the Supreme Court is supposed to be an institution that rises above the politics of the day, so it is not based on trust or a reflection of the culture as a whole. People stopped believing that there is any real truth, or that there were any parents in the room, so to speak. That was what was the most devastating thing about his administration. And then the Republicans who benefit from it knew exactly what they were doing. They were doing a deal with the devil, which they now realise they can’t undo.”

The Trump factor

Stauffer draws his cartoons to remove the blindfold from the delusions people create from the world. But this Trump-inspired trend to demean his work really challenged his art-form, his very career, and that of thousands of journalists around the world. Working within an establishment that somehow reverses itself, it is often very difficult to say with words what Stauffer puts across with pictures. That might have changed somewhat with Trump’s full-on assault on the US media. Many in the media were for the first time forced to adjust to an unreal situation where the politician was turning on his critical audience.

Stauffer draws his cartoons to remove the blindfold from the delusions people create from the world. But this Trump-inspired trend to demean his work really challenged his art-form, his very career, and that of thousands of journalists around the world. Working within an establishment that somehow reverses itself, it is often very difficult to say with words what Stauffer puts across with pictures. That might have changed somewhat with Trump’s full-on assault on the US media. Many in the media were for the first time forced to adjust to an unreal situation where the politician was turning on his critical audience.

“After the first six months of his term, I had a near nervous breakdown because of the depression,” Stauffer admits. “It was a very dangerous time as I was completely disillusioned with what I thought the world was and my faith in it.

“I’d go and see people who worked at the New York Times, and they looked like they had been in prison camps. They were gaunt from the strain of not only working 24 hours a day reporting on a new outrage every other news cycle; but also seeing that the work they were doing was being discredited and stripped of its value because someone was saying it was all fake. Of course they knew it was not fake.”

Trump’s refusal to rebuke Saudi Arabia for its alleged murder of reporter Jamal Khashoggi brought this situation to a head. It challenged the traditional role of the press as the fourth estate of the United States. “Well, will anybody really know?” Trump had asked rhetorically when challenged about the journalist’s death. In response, Stauffer stayed up for two and a half days to illustrate a series of 18 pieces about Khashoggi’s legacy, ensuring that no-one would ever forget the courageous reporter who stood up to Saudi Arabia’s nefarious human rights record.

Breaking the infallible

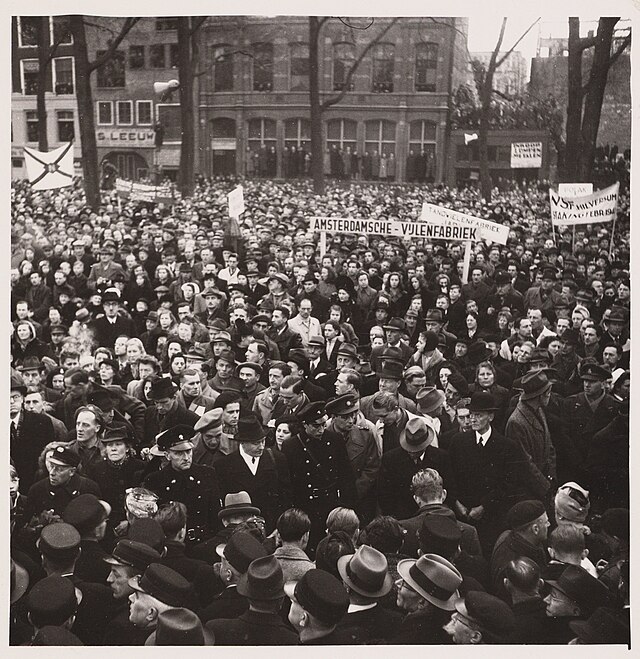

This frustration and anger pushed Stauffer to make public figures more accessible to the general public, to show them public figures were anything but infallible. This fallability only increased under Trump, who Stauffer saw as trying to politicize the pandemic, leading to over a million US deaths. He pointed out that one of his inspirations was none other than the German John Heartfield, whose visual work mocking Hitler forced him eventually to flee the Nazis to England.

“One of the things that I loved the most about John Heartfield is that he he was able to take these images and the way that the public looks at -let’s say a news photo of an authoritative figure – when we kind of consider them untouchable maybe in some way. And then you turn around and you make them touchable,” says the illustrator.

“You show the weakness within the person that is supposed to show that they are perfect or out of reach. And to me it’s very exciting that an individual can take an image for a metaphor and apply it and put that image out and nothing can take it away. What I try to do is to distill complex issues down to something, maybe an essence of it that isn’t necessarily the entire truth.

About the production process, Stauffer points out that it is not so much about the tools but the ideas, even preferring to use a mouse than a digital pencil, for example.

“So there are times when I’m using only only little scans or drawings that will make it into my work,” he says. “I have a number of textures from old magazines that I’m using just the texture as kind of a raw material and I’m duplicating it and cloning it. I use the computer as a very blunt instrument. I still work with with a mouse instead of with a digital pencil and tablet which usually surprises my students.

“They look at me like a dinosaur, which I guess I kind of am technologically but I use the computer in a way that a draughtsman would use a knife, glue and an airbrush. As much as I would love to say here’s what I do every time, it changes so much for every image. And what that has done is that the people now come to me more for the ideas that I’m bringing to a subject than distillation of a concept of a complex story.”

War: What is it good for?

Although Stauffer’s exhibition coincides with the most high-profile European conflict since World War II, he did not plan it this way. In fact, he started organizing the exhibition a year ago, and could not believe that we would now once again be facing the same nuclear holocaust scenario as during the Cold War. “Clearly I’m not happy – but what amazing timing!” he says. “I mean, it’s nice to have these messages because maybe people are looking with a little more intent these days.” However, two of the pieces at this exhibition were made expressly for the Ukraine war – one which was published in ‘Der Spiegel’ and the other to US independent publication ‘The Nation’. That the graphic artist has never diluted his anti-militaristic stance is a testament to his values and his desire to halt injustice and violence.

Although Stauffer’s exhibition coincides with the most high-profile European conflict since World War II, he did not plan it this way. In fact, he started organizing the exhibition a year ago, and could not believe that we would now once again be facing the same nuclear holocaust scenario as during the Cold War. “Clearly I’m not happy – but what amazing timing!” he says. “I mean, it’s nice to have these messages because maybe people are looking with a little more intent these days.” However, two of the pieces at this exhibition were made expressly for the Ukraine war – one which was published in ‘Der Spiegel’ and the other to US independent publication ‘The Nation’. That the graphic artist has never diluted his anti-militaristic stance is a testament to his values and his desire to halt injustice and violence.

“For me, what’s very difficult is understanding the criticism that anyone who claims to be against war is naive and doesn’t understand the dark forces within the world and that, when left to those devices, they would be the first to be slaughtered,” says Stauffer. “It’s a very simple way of dismissing the idea of questioning why we use the destruction of human life as a solution – whether you are the victor or the terrorists, or the victim seeking revenge, or for any justification.”

He addresses the idea of war in several illustrations, one which ironically depicts a peace sign in the shadow of a drone. Even though the West has supported Ukraine’s self-defence using drones, he says that some people even thought it meant that drones helped to keep the peace.

“What I was actually talking about was the sick irony of having to kill somebody in order to make peace,” he remarks.

“I think the taking of life is wrong. Personally, I just do. My oldest child, Andy, when they were maybe four, came to me and saw that I was working on a project. And they said to me, that if we were trying to make friends with them, why do we drop bombs on them.

“You’re gonna say, ‘oh, it’s much more complicated’. Well, the truth is, it’s a very clear distillation of the contradiction and although it’s uncomfortable to face, the truth is that to kill someone in the guise of making peace or pledging forgiveness is the ultimate hypocrisy!”