Berlin – Yellow, red and green balloons float over Hermannplatz in Berlin. It is the 27th of November, 2021. Some thousands of people gather on the square to protest under the slogan “Cancel the PKK ban! End the war – find political solutions!” They plan to march through Berlin. The date of the protest was no coincidence. Exactly 43 years earlier was the founding of the working class party in Kurdistan (Partiya Karkerên Kurdistanê) – abbreviated PKK. Also not a coincidence was the date of the party’s ban, on the 26th of November 1993. To protest against this, people had gathered at Hermannplatz.

Many of the protesters appeared with paper signs, banners and flags. Most of them

were painted in the colours of the Kurdish freedom movement: yellow, red and

green. Alongside the main demand of an end to the PKK ban, there were also calls for the release of Abdullah Öcalan, one of the founders of the PKK. Already at the opening demonstration, the the police started their first advances against a few activists. The police alleged that the protestors had some flags with the symbols of YPJ and YPG on them, which are the self-defence units of the Kurdish freedom movement. Also, all pictures of Abdullah Öcalan amounted to “a bankruptcy declaration for a democratic state like Germany”, said Martin Dolzer. He is the director of the demonstration and the one who registered it.

Dolzer has many years of experience with the registration and direction of large demonstrations. He said that the cooperation level from the police on that day was one of the worst he ever experienced. The ex-politician (2015-2020 Mayoralty in Hamburg) said that the police aggravated the protest from the beginning. But the state troops didn‘t set special conditions for the situation at the Hermannplatz, according to Dolzer. Nevertheless, they forced him to start the rally directly. At that moment the police already threatened him with the dissolution of the rally, Dolzer told us afterwards.

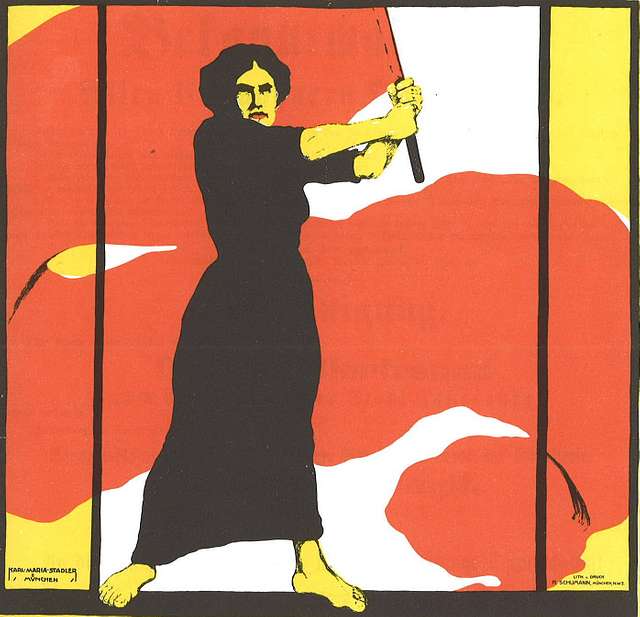

FLINTA* Block declares: PKK means feminist revolution

Only a few meters further, as the rally reached Sonnenallee, the demonstration was halted by police. Near the tip of the self-declared FLINTA*-Block (Women, Lesbian, Inter-, Trans-, A-Gender) , around 30 police officers get ready. A few moments later, they ran into the demonstration to rip the front banner away from the demonstration block. It’s one of two banners that the police would seize over the course of the day. By the time the demonstration reached its end at Oranienplatz, they would add three paper signs, snatched from the rows of demonstrators to the total. The reason for their interventions was that “the imprint had criminal content according to the Freedom of Assembly Act”, the police of Berlin stated later. The text of the front banner of the FLINTA*-Block showed in big letters „Weg mit dem Verbot der PKK“ (“Down with the PKK-Ban”) on the left and the right side of the banner showed a star in the style of the Kurdish freedom movement.

After the stop, the rally continues further along Sonnenallee. From the FLINTA* Block come chants of”Jin, Jiyan – Azadi”, which means “Women, life – freedom”. On a banner high over the crowd “The defence of life is not illegal” can be seen. Next to the text it shows a woman from the Kurdish resistance fighting units, behind her, colorful flowers. All around the raised banner were Ialso a lot of signs holding the words,: “PKK means feminist revolution”.

Around 5,000 people showed up at the rally despite a steady drizzle and the corona pandemic, according to Dolzer. The police stated there were around 2000 people. All in all, the rally was very creative and colourful. But there was also a massive presence of the black-clothed riot units of the Berlin police. Afterwards, the leader of the rally criticised the massive amount of police units around the demonstration. Publicizing the meaning of the demonstration to the streets of Berlin was made nearly impossible, according to Dolzer.

The big number of police units is a normal thing at pro-Kurdish rallies in Germany, the activist Mazlum S. Bavli told us in a background conversation. Especially at the rallies against the PKK ban, there is always a massive police accompaniment. This year, as in many others, the North Hessen native was on the streets of Berlin. The demonstration against the PKK ban has became a tradition for him, the 33-year-old told us. To him, it is very important to “show a symbol against the PKK ban, even if it is grueling.” But it’s not only the demonstration that has a long tradition. The police presence and and tough methods against protestors are also an annual procedure. Bavli, who is also personally affected by the PKK ban, told us about violence against protestors that happens every year “in one way or another.” The state is investigating Bavli in a 129b-case, meaning he is suspected of being part of a terrorist organisation outside of Germany – a claim that is baseless, he says. The hardline methods of the police would still be seen this year.

As the rally enters Oranienstraße, some activists lit fireworks and distress flares from a roof. Below they unrolled a big banner with the symbol from the forbidden PKK on it. Everybody except the police found this measure of solidarity to be in goodwill. During the last part of the rally, hostilities against the pro-Kurdish demonstration also arose. While many people leaned curiously out of their windows to watch the mass of people go by, some of the residents of Oranienstraße showed the so-called ‘Wolfsgruß’. The hand gesture is the symbol of the ‘Gray Wolf’, a militant fascist Turkish organisation. In Austria, they have been declared a terrorist organization, and this sign is forbidden – making it is a criminal offense. But in Germany, there is no such ban to this day. The crowd reacted to the right-wing radicals with chants of “up with international solidarity”. Also, one banana peel found its way in the direction of the window from where the “Wolfsgruß” came.

The march reaches the endpoint at Oranienplatz, the place of the last demonstration. During the last few meters, some people inside the demonstration were lighting some smoke flares. As the rest of the crowds entered Oranienplatz the activists lit some bigger flares in the Kurdish colours of yellow, red and green.

The march reaches the endpoint at Oranienplatz, the place of the last demonstration. During the last few meters, some people inside the demonstration were lighting some smoke flares. As the rest of the crowds entered Oranienplatz the activists lit some bigger flares in the Kurdish colours of yellow, red and green.

The police reacted. Hundreds of helmeted officers storm into the crowd at multiple points. The situation turns hectic, and people get arrested. In total 22 people were arrested on this day, police said. The number of harmed people on side of the activists is unclear. The police stated that there were no officers hurt that day.

Demonstration organizers blame the actions of the police as provocation. The police strategy at Oranienplatz seemed very similar to the strategy the police used at the G20 summit in Hamburg in the year 2017, Matin Dolzer said. At that time Dolzer was a politician in the parliament of Hamburg. He accompanied the protests against the G20 as a parliamentary observer. After the G20 in Hamburg, the police were fronted with critics from many sides because of their hardline tactics. For the 55-year-old, the police action at the endpoint in Berlin was the peak of a day with disproportionate police behaviour. “It was just a provocation against the activists. The police wanted to escalate the situation”, Dolzer commented afterwards. While some political statements and music came from the speaker van, a classic Kurdish ring dance takes shape at Oranienplatz – because of the corona pandemic, with strangely large distances between people. The police continue arresting people. Demo officials walk through the gathering, reminding people of the mandatory mask rules. All these situations together paint a ludicrous picture.

The activist Mazlum Bavli told us that a journalist got arrested, too. Some videos on Twitter underpin the allegations against her. In the video, you can see the arrest and it is clear hear that the person points out to the officials that she is a journalist, followed by a wobble and the end of the video. When we confronted the Berlin police with this case, they said that they have no knowledge about an arrest of a journalist.

Overall, he is satisfied with the rally, Bavli said. He was most pleased by the diversity of people who took part in the protest. “So many different people who are standing behind the same claim – that gives us strength”, said the young man, who is himself active in a Kurdish cultural organization. In the next years, he will come to Berlin again in November. Although he hopes for more critical relations between Germany and Turkey with the newly-elected German government, he has no hope for a change in the case of the PKK ban in Germany. From his point of view, the pro-Turkish legislation in Germany is based on economic and strategic interests. According to the political science student, a change in the parliament in Germany can‘t change that.

PKK-ban since 1993: The background

What is hidden behind the urge to overturn the PKK-ban in Germany? What brings

so many people to the streets of Berlin every November?

For Martin Dolzer the answer is quite clear: “The demand is a justified one. Because the PKK stands for democracy and peace.” In 2010 Dolzer published his book “The Conflict between the Turkish and Kurdish. Human Rights – peace – democracy in a European country?” The PKK ban is also part of the book. According to the German constitution, the PKK actually should be supported, said Dolzer. It’s in the name of European human rights. Germany is, besides Turkey, the only country in the world that is so repressive against the Kurdish freedom movement and the PKK. Such a prohibition policy is known in no other country in the world. In a background talk, Dolzer stressed the situation in Belgium. In that country, the PKK has a combatant status. That means the PKK is treated as a war party.

From Dolzer’s point of view, the PKK has this status quite rightly, because the PKK is forced to fight. In the older days peace negotiations failed because of Turkey, he stated. The last time was in the year 2013. During the rally, a group of lawyers from Berlin made it known that they wanted to start some legal actions against the PKK ban in Germany. Whether or not it will be effective, we will see over time. There was a lawsuit against the listing of the PKK on the European Terrorist List. On the 15th of November 2018, the court found that the listing was unjustified. So they took the PKK off of the list from 2014 to 2017. But there was no direct impact of the court decision.

Similar to Bavli, Dolzer also claims that the German prohibition policy is the result of pro-Turkish behaviour. From his point of view, there is a German contingent that has an interest in a Turkish military focus on Kurdish Lands. Mostly on the lands where the people try to live in democratic federalism. “In so-called ‘failed states’ it is cheaper to buy gas and oil, then it is from a stable democracy”, Dolzer said. Bavli sees Turkey as a big economic partner of Germany. The Turkish state is one of the biggest clients of the German weapons industry. In addition, around 6,000 German companies operate in Turkey, Bavli stated.

Political reactions from the traditional economic ties are just a logical step in this case. The PKK ban is one of them. The strong economic boundaries between the two states are also the main difference between other countries, for example, France or Belgium. One of the results of the PKK ban in Germany is paragraph 129b. Dolzer is convinced that the paragraph is not compatible with the German constitution. The reason for his opinion is that the decision that gets pursued, is up to ministries and the government itself. But in Germany, there is a separation between the court, law enforcement and politics. The law says: “In deciding, the Ministry shall take into account whether the efforts of the association violate the basic values of a state order that respects human dignity or the dignity of a human person or the peaceful coexistence of peoples and, when all the circumstances are considered, appear reprehensible.”

“It is a fatal sign for democracy when it comes to the point that people who organise protests can be charged for 129b”, Dolzer summarised. In a democracy, it should be desirable that people stand up against war.

Mazlum Bavli who sees himself confronted with a 129b charge, agreed with Dolzer’s point of view: “The paragraph was used before to criminalize Turkish leftists and Kurdish activists. For legal protests, they go to jail for years in some cases. To sell bus tickets is enough to get a charge.” On the other hand, it is necessary for Germany to fight against right-wing terrorism in Germany. But Paragraph 129b has never done anything against fascist terror in Germany because it isn’t used for that, Bavli said. It remains to be seen if there will be some movement on the PKK ban in Germany. In the meantime, the tradition of coming from the whole of Europe to Berlin in November to protest against it will probably remain.