Speaking in the German parliament, the Bundestag, Chancellor Olaf Scholz declared that “antisemitism has no place in Germany.” He promised a “clear stand” against it, and at the time of the speech in late 2023, almost all pro-Palestinian demonstrations were prohibited. This principle does not seem to apply to his own office, however: a portrait of the Nazi war criminal Hans Globke hangs in the Federal Chancellery in Berlin.

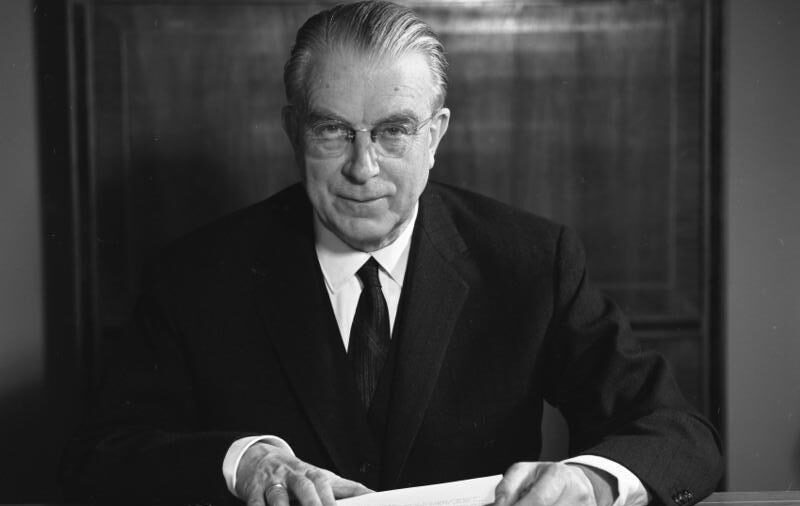

It’s not that the painting has been overlooked in some dusty closet. After the war, Globke served as the head of West Germany’s Chancellery from 1953 to 1963, and today portraits of all former directors hang on a wall. Where exactly? The Chancellery only offers vague answers: “In a corridor in an administrative section.” What does the portrait look like? No answer.

Instead of removing this honor for an antisemitic “desk perpetrator” [someone who did the paperwork to administer genocide], the Chancellory had a “controversial discussion” and decided in 2020 to add a sign to the portrait so that observers could “independently evaluate Globke’s political biography,” in the words of a government spokesperson. The accompanying text ends with the words: “The legislation to which Hans Globke contributed formed the basis for the persecution, deportation, and murder of the German and European Jews as well as the Sinti and Roma.”

The plaque is correct to say that Globke was “co-author of the first commentary on the Nuremberg Race Laws of 1935” — but this only reflects a small part of his crimes. As early as 1932, as an official in the Prussian Interior Ministry, he issued a decree making it more difficult for Jewish people to change their names, so that their “blood lineage” could not be hidden. Later, under Nazi Interior Minister Wilhelm Frick, Globke helped eliminate parliamentary democracy in Prussia. There is evidence that Globke was responsible for the deportation of tens of thousands of Jews from Greece. In short, he was among the people most centrally responsible for the Holocaust.

According to the government spokesman, the painting implies no “judgement” of Globke. A peculiar understanding of how portraits work! With the same logic, they could hang a picture of former German chancellor Adolf Hitler right next to it – without any “judgement” of course, so that everyone could form their own opinion.

Impunity

Globke was never brought to justice for his crimes. After the war, he continued his career as a government official, and was appointed head of the Chancellery in 1953. He was the “brown right hand” of the conservative West German chancellor Konrad Adenauer [brown being the color of the Nazis]. His boss justified this rehabilitation with the words: “One does not throw out dirty water as long as one doesn’t have any clean water!” Globke, in turn, helped numerous former Nazis in the Federal Republic of (West) Germany. As the historian and lawyer Klaus Bästlein told nd, Globke played a “significant role in the re-Nazification of the ministerial bureaucracy in Bonn,” the capital of West Germany.

A criminal investigation into Globke was opened in Frankfurt in 1960, but closed under pressure from Adenauer. Since at least 1952, West German secret services had known that the war criminal Adolf Eichmann was hiding in Argentina. Whether Globke personally covered for this mass murderer has not yet been established. What is certain is that Eichmann had made incriminating statements about Globke which were suppressed on the initiative of the West German government and the CIA.

Globke supported the Reparations Agreement between West Germany and Israel. In the words of Pankaj Mishra, he became a symbol of German-Israel relations: “moral absolution of an insufficiently de-Nazified and still profoundly antisemitic Germany in return for cash and weapons.”

Trial

As a result of this impunity, both in the Federal Republic and in Israel, the German Democratic Republic (GDR or East Germany) took over the prosecution under the principle of universal jurisdiction for crimes against humanity. The GDR’s Supreme Court held a two-week trial in the summer of 1963, and sentenced Globke in absentia to life imprisonment.

Bästlein analyzed the trial for his 2018 book Der Fall Globke (The Globke Case) and concluded that, although the trial was “conducted for reasons of propaganda and not prepared in accordance with the rule of law,” the verdict was nonetheless “legally flawless” and “based on international law.” Accusations of a “show trial” and “propaganda” are often raised — but the evidence is nevertheless clear.

At the time, the main East German newspaper Neues Deutschland described Globke as an “intellectual murderer of millions of Jews.” A few days before the trial, the newspaper quoted workers from the Leuna plant: “We simply cannot understand how such a bloodstained person can hold office in a state today.”

Today it is equally hard to understand. Accusations of antisemitism are leveled regularly against pro-Palestinian activists, even when they are Jewish. Yet when dealing with conservative German antisemites, leniency is the rule. In cases like those of Hans Globke, Heinrich Lummer, or Heinrich von Treitschke, we are told that a historical figure should not be reduced to their hatred against Jews. Bästlein is clear: “Globke was never a democrat nor a supporter of the values of [West Germany’s postwar] Basic Law.” That’s why a clear stand is called for in the Chancellery.

This article was first published in German in nd, it was translated by the author.