It was expected (and almost wanted). The suspicion that Sahra Wagenknecht and a group around her were using party funds to finance a new project had long been hanging over the airwaves. For months, and even years, deputies such as Wagenknecht herself, Dadelem or Nastič did not use the coorporate image of the party in their events and statements, but promoted it as a personal initiative, away from the party. Already in the first half of this year, Wagenknecht announced that she would think about whether to form a party and would make a decision before the end of the year. In response, the leadership of Die LINKE distanced itself from her and expulsion proceedings have since been opened. However, affairs at the palace go slowly and German bureaucracy even more so.

At a press conference on Monday, October 23, Wagenknecht made the definitive announcement of the creation of a party from the association “Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance” (German acronym BSW), a name that gives an idea of the marked personalism of the project. Its political profile is that of ordoliberalism at best, to national-obrerism at worst. It is a nostalgia for any past time which, according to Wagenkecht, was always better and to which she wants to return: the industrial Germany of the sixties, seventies and part of the eighties. She recalls the post-war Welfare State for the white German worker, sustained by an improvement in working conditions, while labor was hired mainly from southern Europe to fill more precarious jobs and with much worse working conditions.

In this sense, Wagenkecht and her nostalgia appeal to an older generation in Germany that lived through both that welfare state in West Germany and state protection in East Germany. However, it would be inappropriate to say that only an older generation could fall into BSW’s fishing ground. Wagenknecht also appeals to migration control policies, claiming that Germany is saturated and overwhelmed by immigration and that the communes (municipalities) have no funds for it. The latter being true, the cause is the neoliberal cutback policies of the SPD, Greens, and liberal government in the budget of the municipalities. With the exception of Die LINKE, the entire German political spectrum — from the far right to the Greens and the new BSW — hypocritically attack immigration, while at the same time campaigning to “recruit talent” from abroad in view of the lack of manpower in strategic sectors such as education, health care, and some branches of private industry. However, Wagenknecht focuses on the external threat, immigration, because it is a rhetoric that quickly connects with a German proletariat, young and old, disenchanted by the impoverishment of their living conditions.

Wagenknecht has also relativized the importance of climate change, as well as feminist, LGTBIQA+, anti-colonial and anti-racist struggles. Similarly, she came dangerously close to conspiracy theories during COVID-19 and proudly took a stand against vaccines. In this situation, the fracture had to come at some point. Die LINKE aims at building socialism, understanding the system of capitalist exploitation in conjunction with the system of sexist and patriarchal oppressions, as well as racist and within the global north-south axis. In addition, it puts at the center combating climate change from a social justice perspective, something that one of Wagenknecht’s acolytes, Klaus Ernst, labeled as “wanting to be greener than the Greens”. However, the Greens put climate policies on the shelf long ago, restarting coal-fired power plants and extending the life of nuclear power plants, cutting down entire forests to build highways, or allowing themselves to be financed by the automobile lobby as in Baden-Würtenberg. Not to mention their passion for war, which, both in the production of weapons and in the performance of war, stands as one of the most potent Klimakillers.

Die LINKE can now make a new start. The last months and almost years have been marked by internal conflict and lack of clarity in positions, with every issue being wrapped up in dispute and unipersonal statements against party resolutions. Particularly active in this have been people from the Wagenknecht circle such as Daǧdelem, Nastič and Ernst. Breaks are difficult, but, as announced by Die LINKE co-spokesman Martin Schirdewan “we can now bring clarity to party policy, once we have finished with the chess game.”

It is to be expected that the new project will be joined by some elected and organic representatives from regional and local politics, as well as party members. However, recently Die LINKE had also lost many disenchanted members due to internal struggles or the fact that Wagenknecht, with conservative positions, had an enormous prominence fed by the media, always ready to fracture left-wing projects. These positions have scared away militants who were reluctant to approach the party or have left it in recent years.

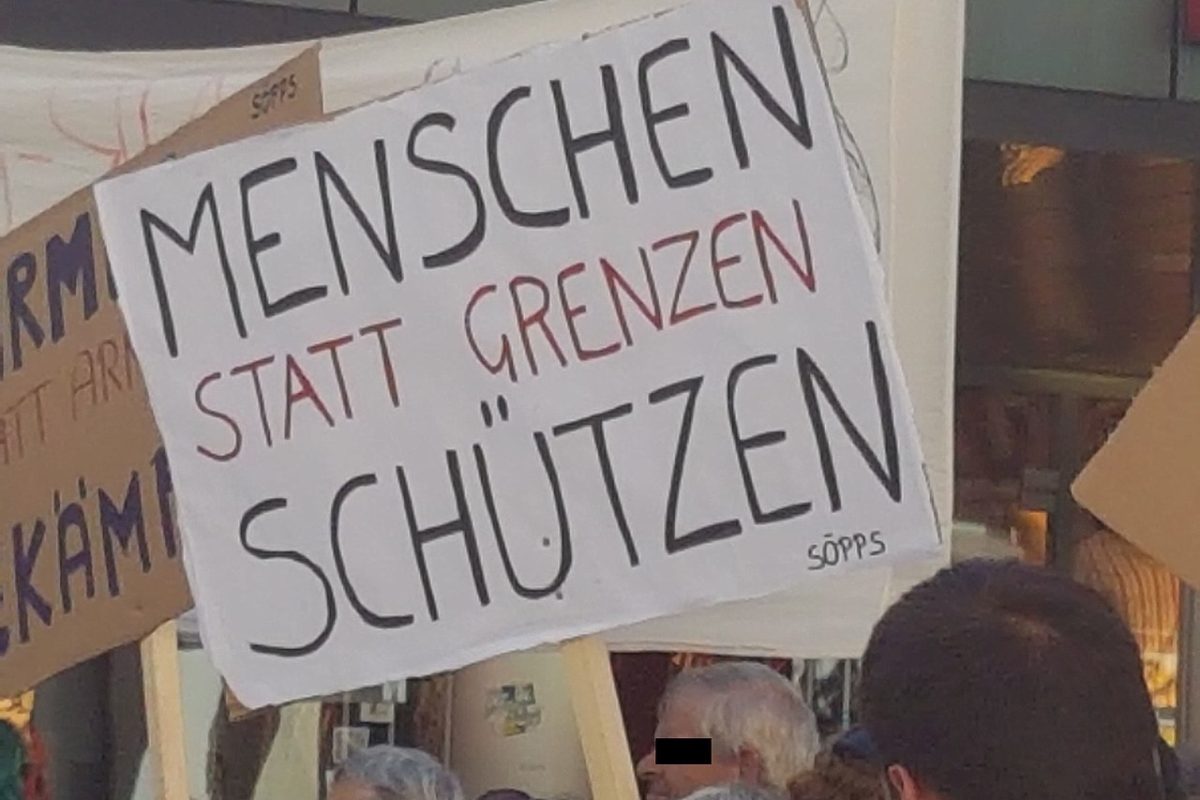

It is, therefore, an opportunity to reconnect with people who were once in Die LINKE and ended up disenchanted, but also to attract SPD and Green voters who do not share their pro-war and anti-immigration policies. Last week, Social Democrat Chancellor Scholz was quoted on the front page of the well-known journal Der Spiegel with the slogan “it’s time to deport people on a large scale”, a slogan used in the past by far-right parties such as AfD or the neo-Nazi NPD. Meanwhile, the Greens have abandoned any policy that really fights climate change, wanting to maintain the capitalist system, painted with an eco varnish, as well as shamelessly nurturing warmongering. In this situation, Die LINKE, freed of burden, can offer itself as a party of the left, anti-capitalism, and in solidarity with migrants. In this regard, the party leadership proposed in the summer the captain and activist Carola Rackete as a candidate together with Schirdewan for the European elections in 2024, something that would be ratified in one month’s time at the Federal Congress of Die LINKE in Augsburg.

These will be difficult weeks in the Karl-Liebknecht-Haus, the party’s headquarters, as well as in every other party headquarters for its approximately 55,000 members. Yet, Die LINKE should now be able to set out on the road with renewed unity in a world that lives in the constant crises of capitalism, which is approaching the abyss of no return in climate matters, and in which war is taking on a very dangerous protagonism. In this context, Die LINKE is still needed in Germany and a left-wing project still has a place. The new BSW project, however, is not and will not be.

This article first appeared in Spanish in mundo obrero. Translation: Jaime Martinez Porro. Reproduced with permission