When people hear I am from Romania, they often tell me about the trips they took there at some point. Some people travel to Romania because clubbing is cheap in Bucharest. Others visit Transylvania’s beautiful medieval towns. Outdoors types still hope to find some untouched wilderness in the Carpathians.

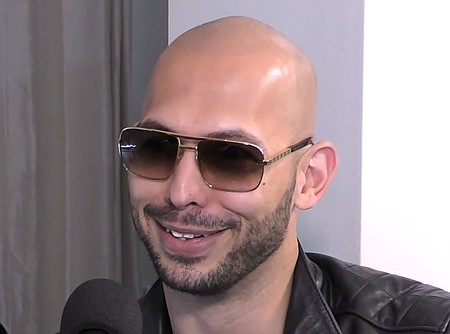

Andrew Tate, former kickboxer, self-proclaimed misogynist, and founder of Hustler’s University, had special reasons to go to my home country. “I like living in countries where corruption is accessible for everybody,” he said in an interview. “I like living in a society where my money and my influence and my power means I’m not below or beholden to any of these bullshit laws.” In case you’re wondering which laws exactly, Tate provided the answer in a now deleted video. “40% of the reason” he moved to Romania was that “in Eastern Europe none of this garbage flies.” The garbage? Police believing the victims of rape in the MeToo era.

On December 30th 2022, the garbage did fly, and Andrew Tate, his brother, and two Romanian collaborators were arrested for human trafficking, rape, and forming a criminal group. Even though the poetic-justice version of the story, involving an unrecycled pizza box and Greta Thunberg, is not true, there has been enough coverage of the investigation to reach even those lucky enough not to have heard about Tate before.

Some of Tate’s followers are fanatic enough to take to the streets and fight against the “agents” of the “Matrix” who arrested their idol. The rest of us might find such sci-fi possibilities less concerning than the actual miscarriages of justice. It recently came to light that in 2015, before moving to the Wild East, Tate was arrested on suspicion of sexual assault in the UK. But the Hertfordshire Police waited four years before passing the case to the Crown Prosecution Service, who then promptly decided not to pursue the investigation.

Before his recent arrest, it had perhaps been easy to dismiss Tate as an online grifter and his followers as impressionable boys. Even now, when World Vision Romania sketched a profile of the audience susceptible to Tate’s appeal, it only referred to rural male teenagers, affected by poverty and looking for a way out, who receive insufficient attention from their parents. These boys see themselves as superior to women and as deserving more than they get. The only place for them to turn to for validation is the internet – where they receive it in a systematic manner.

Misogyny in Romania

This portrait will not be unfamiliar to anyone aware of the conditions in post-socialist Europe. Neoliberal transitions precaritized millions and left them grasping at individual solutions of upward mobility. Upward or outward. The unofficial estimate of Romanian children with at least one parent working abroad is 350,000. Because of migration or other reasons, many Romanian boys may lack “positive role models,” as the World Vision study puts it. Does that make them vulnerable to being sucked into online worlds of misogyny and grifting? Undoubtedly. And it is essential to properly recognize the systemic economic pressures that have shaped younger generations in a semi-peripheral Romania. But that should not lead us to ignore the fact that Romania is a deeply patriarchal country where violence against women is itself a structural issue, and a hotbed of human trafficking in the EU.

Because, after all, Tate was not wrong in his vile optimism about Romania’s law enforcement. The FILIA Center, a Romanian feminist organization, notes that in 2021 around 75% of the rape and sexual assault cases in the country were closed by dropping the charges. Another study shows that in 2016, out of 27,000 complaints of domestic violence, only 1,467 went to trial. The same source estimates that three quarters of women who suffer from sexual abuse at the hands of a partner or former partner do not register complaints. Romania is a country where silence and coverups are still the norm, due to the lack of material resources, of crisis centers, and of support systems, and due to the egregious behavior of the police themselves.

Tate’s declarations show that this, for him, is a business opportunity. A Romanian commentator reacted to the World Vision study by agreeing that the problem it highlights is real. But the violent entitlement to women’s bodies is not isolated to the Romanian countryside. He notes that Tate is selling not only power over women, but also financial power. This draws in both the Romanian youth lost in transition and the young men who have (temporarily) won at the neoliberal game. They hope that Tate will show them not only the secret to sex, but also how to use their money to make more money.

The swindled, not the swindlers

Some of Tate’s Romanian imitators and associates have indeed been successful, such as internet personality Vlad Obu, who has also come to the attention of Romanian law enforcement in January. But most of Tate’s fans are the swindled rather than the swindlers. 1,000 of them, lacking any sense of irony, paid $100 for a “Resist the slave mind” t-shirt. The website of “The Real World” (Tate’s continuation of Hustler’s University, shut down in 2022) claims 200,000 members – paying $49.99 a month. Tate does have a secret that helped him make millions. But that secret is convincing others that paying him money will make them rich.

If Tate is not offering actual money-making techniques, what is he selling his fans? The answer is masculinity and power. He is selling the illusion that he can help them get what they feel they have been denied: money, sex, power. Because violence and control over women secure men’s position in the family and the community, a demand for what men believe they are entitled to but do not receive. Tate made this clear in his reasons for coming to Romania. He is a man with immense fame and money and he believes that this entitles him not only to more fame and more money but also to literal ownership of women’s bodies, to power over others, and to a certain social standing.

Capitalism, pornography, and power

Tate is, after all, a capitalist, and his justified belief that in Romania he could treat women and the law as he saw fit was also a belief that he could gain money and influence in the Eastern European sex work market. Although the sexcam industry is a legal gray area in Romania, it is also booming. A studio manager gives three reasons for this: “poverty, an abundance of underemployed beautiful women who speak English, and exceptionally high-speed internet.” Although factually accurate, such a framework might play into neoliberal disguises of insecurity as flexibility and of constraints on opportunities. Some of the estimated 100,000 models in Romania have indeed found their ticket out of precarity. But many of them are stuck in the “intricacies of platform capitalism” and in “asymmetric staff power relations.”

Nothing makes this clearer than the investigation into Tate’s own sexcam business. The human trafficking accusations refer to the “loverboy method:” Tate would promise young women that he would marry them before forcing them into producing pornographic material on OnlyFans and TikTok. He did not choose to do this in Romania on a whim. Online pornography follows the same global structures of capitalism as other digital platforms that thrive in the periphery and semi-periphery. High inequality, lax law enforcement, cheap labor, all make Romania a key link in the “global value chain of the sexcam industry.” While sexcamming itself might be semi-legal, it depends on a dark underside of trafficking and constraining young women (and sometimes men) into an informal infrastructure of studios. A dark underside that is by no means exclusive to online pornography: either industrial or sexual, forced labor is an intrinsic part of the capitalist (semi-)periphery.

What Tate makes painfully visible is how capital depends on and benefits from structural gendered and sexualized violence. His case also shows that the state is far from innocent in all of this. It is not yet proven that Tate’s boasts about using corruption in Romania to his advantage were true, although I would be surprised if they weren’t. What we do know, however, is that many of his Romanian employees and collaborators were former police officers or special agents.

But this story has a happy ending, right? Tate has been arrested and will hopefully be punished. This shows that the sustained anti-corruption campaigns of the Romanian state and civil society are working, and things are changing. But while few would deny that Tate’s arrest is a good thing, the issues are much bigger. After all, anti-corruption in Romania has meant cementing the country’s integration into European and global capitalism – the same capitalism that made Tate’s success possible in the first place. Someone will soon take his place in both the sexcam industry and in the online manosphere, someone who will now know better than to boast publicly about paying off law enforcement and will fit right in. Andrew Tate is a symptom of global structures of capitalism and gendered violence. He might soon be gone, but the structures remain.