The strategy of Antifascist Action can only be understood in the context of the policy of the German Communist Party (KPD) at the time, which in turn was framed by Stalinism. With the rise of Stalin in the USSR during the 1920s and the liquidation of what remained of the 1917 Russian revolution, the communist parties of the world turned into instruments of Soviet foreign policy.

For some time following 1928 (while they were completing the counter revolution inside the USSR), it suited the new Russian leaders to use very radical ultraleft rhetoric, in what was known as the “third period”. According to this position, all of Europe was in the hands of fascism. It is true that Italy was controlled by Mussolini’s fascists, but in Germany the establishment parties — the Christian Democrats and the Social Democrats — were still in charge. This was no problem for the Stalinist theory; they were simply branded as fascists and in the case of the German Social Democratic Party, the SPD, as “social fascists”. (See Rosenhaft 1983, pp28ff.).

So during the rise of Hitler the KPD, in general, fought against the Nazis, but always from the viewpoint that the SPD was an enemy as or more dangerous than the fascists themselves.

According to Poulantzas: “there seems to have formed a ‘current of opposition’ [within the KPD] in 1931… which advocated both a stronger fight against Nazism… and that the main blow be struck not against social democracy but against Nazism. However, nothing was done” (Poulantzas 1970, p216).

In 1932, the KPD group in the regional parliament of Baden presented a bill to ban the Iron Front and the Reichsbanner, the Social Democratic Party’s combat organisations (Poulantzas 1970, p210. The KPD central leadership condemned the proposal). Needless to say, the occasional calls the communists made to the SPD rank and file to join the KPD’s anti-fascist struggle didn’t sound convincing.

At times the KPD came worryingly close to the Nazis. In the Land, or region, of Prussia, in summer 1931 the Nazis began a campaign to overthrow, through a referendum, the SPD’s regional government. Initially the KPD refused to support them, but after the intervention of Moscow, the party supported the fascist campaign (Gluckstein 1999, p114, Poulantzas 1970, p213).

In November 1931 the KPD newspaper published an open letter to the “fellow workers” of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) and the stormtroopers, declaring that “as honest fighters against the hunger system, the proletarian supporters of the NSDAP have joined the United Front of the proletariat and carried out their revolutionary duty” (Rote Fahne, 1 November 1931, cited in Gluckstein 1999, pp113-114). On 18 May 1932 —exactly the period in which the Antifa movement was being prepared— the KPD organised a public meeting with the participation of a Nazi speaker and three hundred NSDAP supporters. (Rote Fahne, 20 May 1932, cited in Gluckstein 1999, p113).

In November 1932 — just months before Hitler’s takeover, and months after the creation of Antifa — both the KPD and the Nazi trade union, the NSBO, celebrated their collaboration —their “united front”— in organising a wildcat transport strike in Berlin. (Gluckstein 1999, p116).

The creation of Antifaschistische Aktion

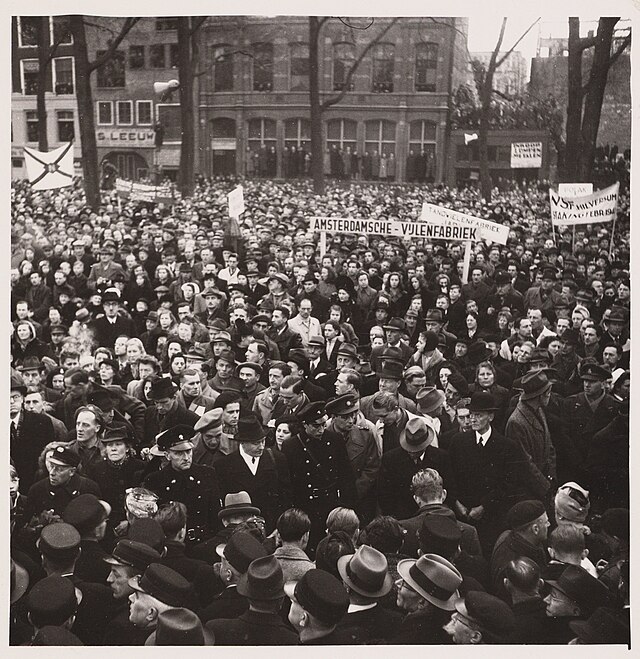

Already in the 1920s, the KPD had had a combat force called Rotfrontkämpferbund or “League of the Red Front Fighters.” Officially banned in 1929, in fact the organisation continued to function. However, in order to act more openly, the KPD announced in its press, in May 1932, the launching of Antifaschistische Aktion, Antifascist Action. The inaugural event — of which there is a famous photo, of a huge hall decorated with the anti-fascist red flag — was held in June 1932.

Initially some KPD leaders wanted the Antifa movement to be more than just a front for the party. There was talk of a possible understanding with the socialists, and in the photo of the founding congress you can see a socialist banner. But this open attitude didn’t last long.

Under pressure from Moscow, the KPD leadership quickly made it clear that Antifa would oppose not only the Nazis but also the SPD: “Anti-Fascist Action means untiring daily exposure of the shameless, treacherous role of the SPD and ADGB [socialist trade union] leaders who are the direct filthy helpers of fascism” (Rote Fahne, 1 July 1932, quoted in Gluckstein 1999, p115).

As it had been doing since 1929, with the Antifa movement the KPD insisted that in order to fight against fascism it was necessary to fight against capitalism. A pact with the SPD was, therefore, unthinkable. Faced with some attempts to create unity from below, the KPD leader, Thälmann, warned in September 1932 against “dangerous conceptions such as ‘unity above the heads of all the leaders’… Such tendencies can bring the greatest damage” (Poulantzas 1970, p212).

In January 1933, just over half a year after the creation of Antifa, Hitler came to power. The KPD leaders, faithful to their “theory of the third period”, gave this fact little importance, insisting that he would not last long and that “After Hitler, we will take over!” (Wilde 2013). Despite all the KPD’s revolutionary rhetoric, and its hundreds of thousands of members, the Nazis took control of Germany almost unopposed.

It must be said that the SPD was not any better. The Social Democratic leaders accused the Communists of being “Red Nazis”, comparable to Hitler’s followers. The best response to fascism, they insisted, was defending the Constitution and the rule of law. To fight against the Nazis, as the communists did, was to lower themselves to their level. And more things in the same vein. In short, the policy of the SPD against Hitler was also disastrous.

Antifa against antifascist unity

There was an alternative. The Russian revolutionary, Trotsky, defended the policy of the united front; an alliance of all left wing organisations — especially the KPD and the SPD — against the Nazis, without hiding the political differences.

In September 1930, for example, he wrote: “What will the Communist Party ‘defend’? The Weimar Constitution? No,… [the] Communist Party must call for the defence of those material and moral positions which the working class has managed to win in the German state. This most directly concerns the fate of the workers’ political organizations, trade unions, newspapers, printing plants, clubs, libraries, etc. Communist workers must say to their Social Democratic counterparts: ‘The policies of our parties are irreconcilably opposed; but if the fascists come tonight to wreck your organization’s hall, we will come running, arms in hand, to help you. Will you promise us that if our organization is threatened you will rush to our aid?’ This is the quintessence of our policy in the present period.” (Trotsky 1930). He continued to insist on this vision until the victory of Hitler. (See also, for example, Trotsky 1931 and Trotsky 1933).

Trotsky had very few followers in Germany but still they tried to put their policy into practice. One of them, Oscar Hippe, recounted the experience later.

During 1931 the Trotskyists in Germany called on the other workers’ parties to push for a united struggle against the Nazis. They specially called on the KPD to help create action committees against fascism with the participation of all the workers’ parties, unions, factory committees, etc. If they were created, these committees should be united through a founding congress to establish a movement throughout the country.

They did not just make statements; where they had a real base, they fought to build united movements against fascism. In Oranienburg, a city near Berlin, much of the local KPD had gone over to the Trotskyists, and Committees for the United Front were established. Their rallies in different neighbourhoods of Oranienburg attracted some six hundred people. Different sectors of the left participated in these committees, including KPD activists, and in some neighbourhoods the SPD as a party.

Hippe adds, however, that “the KPD always tried to break up the committees”. It is interesting that the experience of the united struggle against fascism fostered unity in other areas. A unitary unemployed workers’ movement was established in Oranienburg, which led a demonstration of 2,000 people to the town hall. The leadership of the KPD did everything possible to sabotage the unitary model. In Berlin, they mobilized the communist youth — activists who probably also belonged to the Antifa movement — to attack with clubs and stones those activists who put up posters or painted slogans in favour of the united front against fascism. (Hippe 1991, pp128-132).

In the end, neither Trotsky’s warnings nor his followers’ attempts to put their strategy into practice managed to break the resistance of the two big parties, except in isolated cases such as those described above. Hippe explains that at the beginning of 1933, “The desire for unity existed among large parts of the working class; only the leaders of the two workers’ parties worked against it. The KPD did not want to back down from its theory of social fascism, while the leaders of the SPD played down the dangers and based themselves on parliamentary activity. We went into 1933 in the knowledge that the victory of Fascism could no longer be prevented. In the final four weeks, our activities increased in spite of everything… “(Hippe 1991, p136).

Pacts with the bourgeoisie, and with Hitler

To complete the picture of the lack of principles of the Stalinist leaders who had promoted the strategy of Antifascist Action, we must remember what they did over the following years. After the terrible defeat represented by the destruction of the German working class— the strongest in Europe — in 1933, the foreign policy of the USSR made a 180-degree turn. In 1934, Moscow began to promote the politics of the popular front. Only two years after helping divide the German working class because of their differences with the Social Democrats, now the communist parties had to ally with “the progressive bourgeoisie”.

In 1935, Stalin signed a military pact with France, then still one of the world’s leading imperialist powers. Pierre Laval signed the deal on behalf of the right-wing government of France. Months before, Laval had met and come to an agreement with Mussolini, giving the green light to the imperialist ambitions of fascist Italy in Africa. Far from insisting on opposition to capitalism as a precondition, with the popular fronts the communist parties repressed those sectors of the left and of the working class that wanted to break with capitalism — all in the name of maintaining “unity”. The central objective of this policy was a broader pact, which was not achieved at that time, between Stalin’s USSR and the imperialist bourgeoisies of Great Britain and France.

When this strategy failed, Stalin did another about turn in 1939 and came to an agreement with Hitler. Again, one assumes that he did not demand that the Nazi leader reject capitalism.

Conclusion

The disastrous failure of the anti-fascist action strategy should serve as a warning to activists who want to stop fascism today. Sadly, in general, that is not the case. In a future article we will look at how sectors of the current antifascist movement repeat many of the mistakes of the past, running the risk of repeating the same tragic end.

Postscript of 2019

I just discovered an article entitled “For the organisation of the Anti-Fascist United Front in the Workplaces”, in the Euskadi Roja(newspaper in Euskadi of the Communist Party of Spain), 23 December 1933. Eleven months after Hitler took power, they continued to reproduce the tragic errors of the Antifa strategy.

The call starts well:

The European Anti-Fascist Workers’ Congress decided to elect a Central Committee of Workers’ Antifascist Unity of Europe [whose tasks include]:

3. Intensify the efforts to constitute the broadest antifascist front of all workers, employees, petty bourgeois, poor peasants and intellectuals in the fight against fascism and imperialist war.

The creation of the broadest front of struggle of all anti-fascists, without distinction of party, union tendencies or religion, of all those who are ready to unite to annihilate fascism…

The problem is that this apparent desire for unity was not real. A few lines later we read that they propose:

5. A determined fight against all saboteurs of the antifascist united front and tirelessly denounce the support provided by the Second International and the reformist trade union leaders who have paved the way for Hitler, Mussolini, Pilsudksi, etc., who have sabotaged the anti-fascist struggle and who aim to continue to lend their support to fascism.

That is to say, just as in Germany in 1932, they were proposing a united struggle “without party distinction”… on the basis of denouncing the social democrat party. As we have seen, a few months later, Moscow began to turn towards the strategy of the popular front, of pacts (without conditions or denunciations) with the “progressive bourgeoisies”.

This article originally appeared in David Karvala’s Spanish-language book El Antifascismo del 99%. The chapter explores the origins of “antifa” (an abbreviation of the German name “Antifaschistische Aktion”), which was an organization of the German Communist Party in the 1930s. Reproduced with permission

Bibliography

Gluckstein, Donny (1999), The Nazis, capitalism and the working class, Bookmarks, London.

Hippe, Oscar (1991), …and red is the colour of our flag, Index, London.

Karvala, David (2012), “La larga sombra del estalinismo”.

Poulantzas, Nicos (1970), Fascismo y dictadura: La tercera internacional frente al fascismo [There seems to be no online version in English]

Rosenhaft, Eve (1983), Beating the Fascists?: The German Communists and Political Violence, 1929-1933. Cambridge University Press.

Trotsky, Leon (1930), “The Turn in the Communist International and the Situation in Germany”, 26 September 1930, Available at

Trotsky, Leon (1931), “The Impending Danger of Fascism in Germany: A Letter to a German Communist Worker on the United Front Against Hitler”, 8 December 1931.

Trotsky, Leon (1933), “The United Front for Defense: A Letter to a Social Democratic Worker”, 23 February 1933.

Wilde, Florian (2013), “Divided they fell: the German left and the rise of Hitler”, en International Socialism 137, winter 2013.