The internet is under attack, and Western politicians have been quick to point their fingers in Putin’s general direction. Two underwater telecables in the Baltic Sea were cut Sunday night and Monday morning this week. One connected Lithuania to the Swedish island of Gotland, the other ran from Finland to Rostock in Germany.

Despite few details, on Tuesday a statement by Germany, France, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom claimed — without specifically mentioning the cables — that, “Russia is systematically attacking European security architecture.” The German Defence Minister Boris Pistorius also stated that, “No one believes that these cables were cut accidentally.” He then added, apparently without a hint of irony, “We also have to assume, without knowing it yet, that it is sabotage.”

This is the third alleged attack in the Baltic Sea since the war between Russian and Ukraine began close to three years ago, the first two primarily targeting gas pipelines. It is unclear who carried out the first attack in September of 2022 on a pipeline built to carry Russian gas, but they succeeded in causing major damage. The Americans and the Russians have since blamed each other, although media reports from Germany’s investigation point towards a pro-Ukrainian group.

The second attack in October 2023 was first denounced by Finland as having been caused by “outside activity”, and various European leaders hinted at Russian aggression, only for some awkward information to come to light: a Chinese tanker ship was apparently to blame. It seems to have dragged its anchor along the sea bed and damaged the pipeline, although it’s unclear whether this was due to incompetence or done on purpose.

Again this week, before events were clear, European leaders pointed to sabotage. The day following Pistorius’ bravado statements, it was reported that a Chinese bulk carrier was at the site of both breaches at approximately the times they took place. The signs are once again pointing to an accident, although as of the time of writing, neither the accidental nature nor the Chinese ship’s responsibility have been confirmed.

It would be far from the first time an undersea cable was damaged by accident. According to the telecom data provider TeleGeography, there are around 100 breaks per year, and around two thirds of these come from fishing boats trawling the ocean floor, or inconveniently placed anchors. Add to that natural wear and tear, earthquakes, and the occasional knowledge-hungry shark, and there’s little space left for international intrigue.

The spine of the internet

Underwater telecables are of major structural importance in the modern world, and so perhaps forgiveness can be extended to politicians who panic and point fingers at the possibility of attacks. They were originally used to transfer telegraphs, then telephone calls and now today the internet as well. The cables themselves, alongside fears surrounding them, have a long history — the first international treaty on the matter included the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian empires among its original signatories.

The underwater cables that carry phone calls and internet traffic are surprisingly thin, about the width of a medium carrot, although notably longer. Closer to shore, they are thicker due to increased protective layers. While the landing points are generally considered the most susceptible to attacks, actual attacks have tended to target sections deep underwater, where there are fewer witnesses or risk of escalation than would come with attacking infrastructure located on foreign soil.

During the Cold War, the Americans and the Soviets engaged in a back-and-forth which showed that the underwater sections of telecommunications cables were more than weak enough to be targeted. In 1959-60, five transatlantic cables near the USA were cut one after another, leading to accusations of foul play. The American Navy seized a Soviet fishing trawler which was at the site of each of the cuts, but were unable to prove its responsibility. Then, throughout the 1970s and 80s, the American National Security Agency spied on Soviet communications by having a submarine tap Soviet cables.

More recently, American and other Western political commentators have continuously raised concerns that these cables are a weak point. In 2015, Forbes ran an article titled, “How Bad Would It Be If The Russians Started Cutting Undersea Cables? Try Trillions In Damage”. In 2019, a NATO-associated journal published a detailed piece outlining the risk. Just this summer, the Financial Times published another article warning of the possibility of attacks.

There is a slight irony here, as despite all the alarming articles, the 2019 piece still feels the need to offer what feels like fairly basic advice to those who run the supposedly high-risk landing ports: they should implement “perimeter fences”, “video surveillance cameras” and “guard[s]”.

There are admittedly some good reasons to be afraid. Even today, upwards of 95% of internet traffic is run through these cables, despite all the attention given to satellites. The WhatsApp messages you send from your phone to family or friends abroad go to the nearest cellphone tower, and then straight into a cable. Add in work emails, the recipe you looked up on an Indian website, the German website you used that has servers in the USA for whatever reason, and of course, trillions of dollars in digital transactions swirling around the globe; everything from grandma sending you birthday money to grandpa’s tax-dodging offshore accounts.

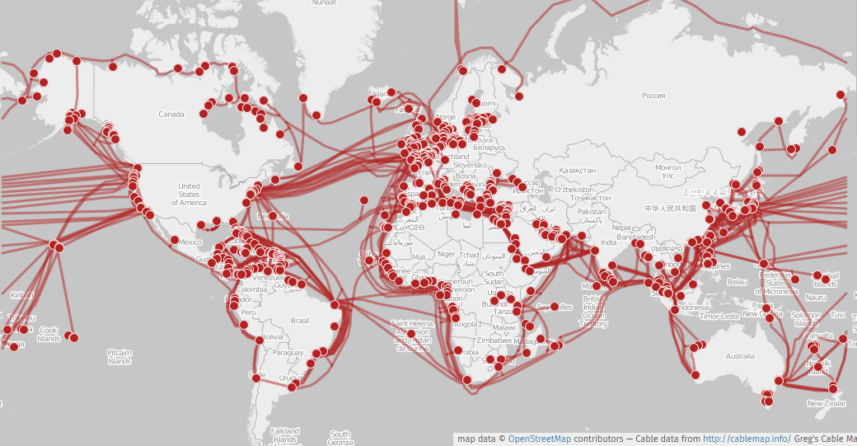

All this information is primarily run through undersea cables. As seen on this map, most places have enough cables that just cutting one would be more of a costly inconvenience than an economic and security crisis, as data could be re-routed through other cables with little or no noticeable loss in service.

This is true of the current situation in the Baltic Sea, although Finnish users may find their internet slightly slower than normal. Some geographically remote places like Australia or Patagonia are exceptions, though. The Black Sea is also surprisingly sparse on cables.

Serious outages, even short ones, would prove costly to the financial markets, not to mention the cost of repairing the cables. But in times of war, any damages to communication lines could have costs ranging well beyond the economic, interrupting the flow of communications to military forces — not to mention the psychological impact such an attack would have. Youth across Europe have already been struggling with the rising costs of bread since Russia invaded Ukraine. How would they manage if Putin shut down their internet?

Privatisation and confused jurisdiction

Despite their importance and the long-standing international agreements relating to them, the actual jurisdiction over undersea cables is still quite confused. This is made worse by the fact that most of these cables are privately owned, a fact as unsurprising as it is depressing. Major corporations like Google are becoming increasingly responsible for them as well, with industry insiders claiming just last month that Meta has plans for a new around-the-world cable.

In the Baltic Sea breaches, the shorter Lithuania-Gotland cable belongs to the Swedish company Arelion. The other cable leading to Rostock was the 1173 km long “C-Lion1”, owned by the Finnish company Cinia and originally built in 2016. Cinia has said that a ship is being dispatched, and repairs should be completed before the end of the month.

The muddled political jurisdiction was shown by the response to the alleged attack on the Finnish and Swedish companies. Both countries launched inquiries from their respective national investigative bodies, although the Finnish allowed the Swedes to take the lead. This was presumably because at least one (but seemingly both) of the cuts was close enough to Swedish shores to be in the Swedish Exclusive Economic Zone, as Cinia said in its statement.

This left Germany (not to mention Lithuania) in the awkward position of wanting to be outraged by an attack on their internet infrastructure, but having nowhere to funnel this anger. It was, after all, an attack on a Finnish-owned cable on Swedish territory. The only impact it had on Germany was on its internet, leaving the state with no investigations to launch or other practical ways of showing displeasure. Pistorius had to make do with an accusatory and potentially embarrassing statement. If news comes out confirming that it was an accident due to the Chinese ship, he may end up hoping more damaged cables prevent the news from spreading this close to an election.

As mentioned above, whether Putin is behind these latest cuts or not, it certainly isn’t the first time European governments have too quickly accused Moscow, nor is undersea sabotage a new tactic. But while the ringing of war bells is a cause for concern, the largest threat to internet infrastructure over the long term may be massive corporations seizing control of our means of communication by building and purchasing the cables that connect the world. With the growing monopolisation of these cables, the main threat to the freedom of the internet may be on a Meta-level as well as a physical one.