Patrick Bond is Distinguished Professor at the University of Johannesburg Department of Sociology, where he directs the Centre for Social Change. We have asked him to share some thoughts on the US attack on Venezuela.

The US attack on Venezuela is not unprecedented but nonetheless extraordinary. What do you project the immediate implications of it to be?

Well, it’s an indication that Donald Trump is starting 2026 as the maximum bully. And I think we’re going to see him gain confidence for his neoconservative militaristic side, and he will also threaten the governments of Cuba, Nicaragua, Colombia, Panama and maybe Denmark, in terms of control of Greenland.

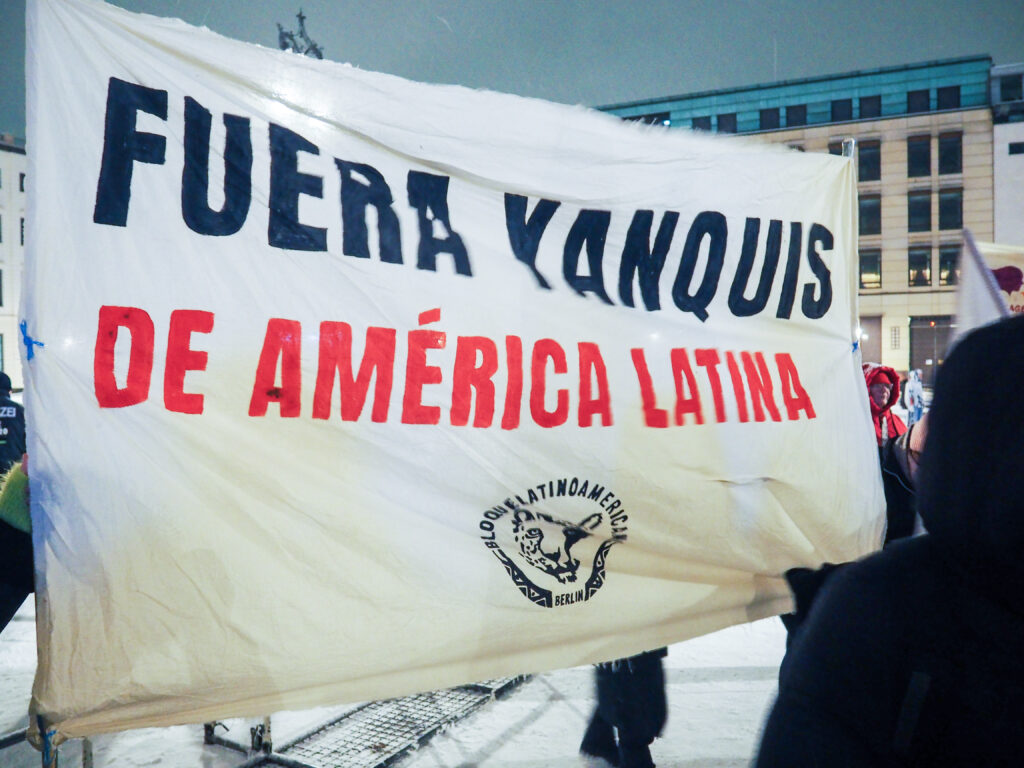

So we’re now in a very lawless, wild-west period in the Western Hemisphere that follows the national security report of Marco Rubio, which basically says, “the Western Hemisphere is ours”. The old 1823 Monroe Doctrine – claiming that the US will control that area – is now being called the Donroe (Donald Donroe Trump) Doctrine. And that is something I think the world must wake up to and say, “no you can’t do that”.

America’s NATO partners were quiet when America did this in Iraq and once again in Syria. And of course we saw what they did in Libya with the regime change of Gaddafi. What does the world stand to lose this time around if they once again turn a blind eye?

Donald Trump will be empowered to continue with his regime change agenda. He will probably feel the need to do that in the period between now and November, when he will face tough elections for his members of Congress: the House of Representatives all turn over, plus a third of the Senate. We can often see these sorts of interventions as a distraction, as a way of exerting power abroad when things are going badly at home. And I think that’s probably part of the calculation this year.

The other aspect is the hypocrisy of the G7. There’s a G6 which is Europe, Canada and Japan, and Donald Trump has broken free. He did not come to the G20 here in Johannesburg, and he also dropped out of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change – which means the US is violating the world’s responsibility to cut emissions. He also quit the World Health Organization, which throws pandemic preparedness into question.

In the first sixth months of 2025, Elon Musk, our South African born-and-raised ally of Trump, cut USAID, which operated as the main agency for overseas development, healthcare, climate support, food and emergency aid. A report in the Lancet says that means 14 million lives will be threatened by 2030.

What more? Bombing Iran in June. Supporting the genocide in Gaza by giving Benjamin Netanyahu free reign, as he just did this last week. It is really time to ask what can be done now, to say this rogue activity must be stopped. On trade, we saw divisions, and only one country stood up to him on the tariffs. That was China, who said, “we’ll put sanctions on you with the rare earth minerals”.

I think that was a signal that, actually, Trump can be forced to back down. The Houthis forced his Navy out of the Red Sea in May by virtue of their drones, and being able to shoot down US drones. And I think there are moments where you see some resistance. We all have to remember what his own vice president JD Vance said: Donald Trump could be the next Adolf Hitler. When he said that, just before the 2016 election, we didn’t really know Trump. Well, now we do, and I think we do have to worry that there is an expansive, arrogant, and, as our foreign minister says, “white supremacist” point of view, that led him into this attack on Venezuela, which I think the world now must stand up against.

What we learn from Syria, Iraq and Libya to an extent is that often an invasion of a country leads to insurgencies on the ground. And regularly that leads to protracted wars, which forms the pretext of America’s continued “war on terror”. Do you anticipate that would happen in this instance as well?

Well, just add Afghanistan. That was the crucial insurgency, with the Taliban coming back and in 2021 Joe Biden – Trump’s predecessor – actually felt the need to pull out US troops. So it can be done. Iraq has not gone well. The US lost quite a few troops there when they invaded in 2003.

The vice president, Delcy Rodriguez, is a loyalist and coming out of the Chavez tradition, the left. But according to Marco Rubio, he talked to her and said, “she’s willing to do business”. Interestingly, Trump said that the popular middle-class leadership, including the Nobel Prize winner María Corina Machado, isn’t ready to take over. Edmundo Gonzalez was the candidate against Maduro in 2024.

At that point, Maduro didn’t really prove that he’d won the election. He just said he’d won. They never released the ballots and therefore he lost the support of, for example, Lula in Brazil, or Mexico’s president at the time Andrés Manuel López Obrador, or president Gustavo Petro in Colombia. The left didn’t hold together to support him.

Cuba’s very weak. Nicaragua was extremely weak, and no longer really a left government. And I think the potential for resistance remains the biggest question, because Maduro was captured and is no longer in Venezuela, unlike in 2002 where Chavez – having been captured and taken away – was returned to power after the masses of the people came back during that coup attempt.

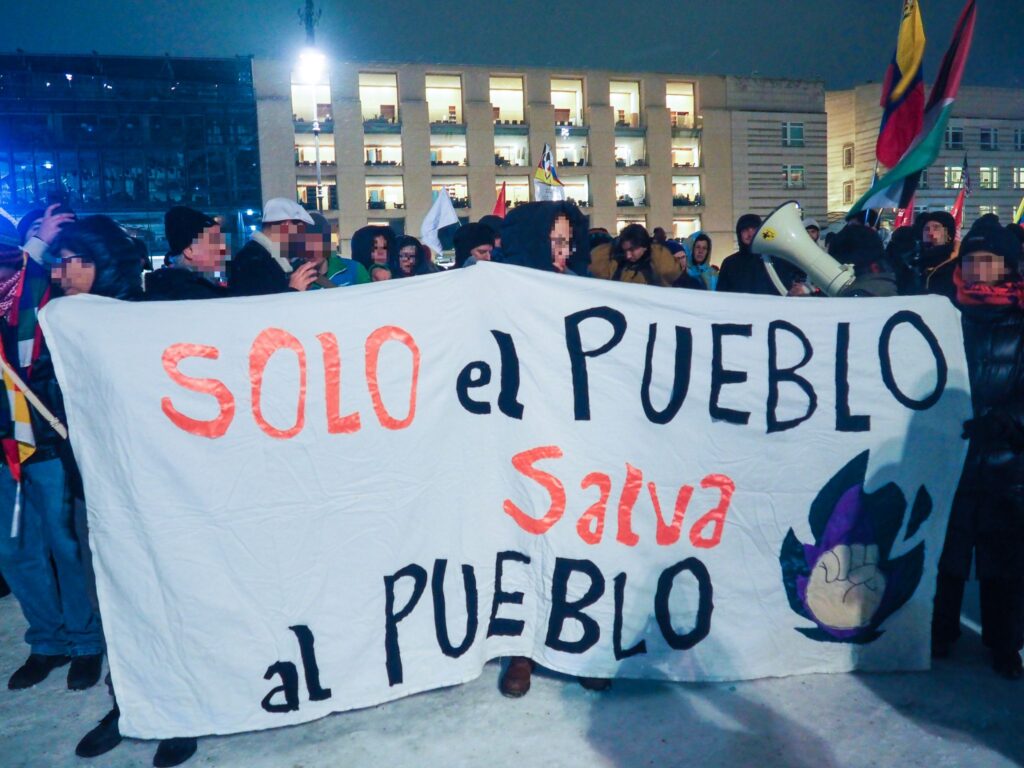

About a decade ago I was a TeleSUR columnist, so I kept in touch, and I’ve been to Venezuela. But if the US invades again, I don’t think that that sort of mass popular support for Maduro can be counted on anymore. I think it’s going to be up to all the rest of us to protest at US embassies and consulates, and start sanctions. Those would be the ways forward if the Venezuelan people call on us, because they feel that the US will really clamp down on any dissent there.

I want to ask about Russia, China, and Iran as well, because they also have economic interests tied to the fortunes of Venezuela and its political stability, for which Nicolas Maduro was an important interlocutor. Do you anticipate that they would throw their support behind Delcy Rodriguez, as she assumes a head of state position?

Probably they’ll make continuing objections, and there may be a debate in the UN Security Council, and probably the US will just veto, and that’ll be that. We’ve seen once before, a coup within the BRICS countries – before Iran joined – that was an internal coup against the Brazilian president Dilma Rousseff. That was in 2016, and there was a lot of discussion then about the potential for the BRICS to say, “we won’t deal with the new president of Brazil”. But they never did. Nor did they react to Trump’s bombing of Iran last year.

That’s the biggest dilemma for the BRICS: they talk left, they walk right. They don’t really do very much to change the status quo. So I doubt we’ll see China, Russia, or Iran standing up. In fact, Iran is probably hunkering down because again, Trump has essentially said, Yeah, Israel, you can go and bomb them. We can take out the Iranians. The popular unrest there now is maybe giving them some sort of excuse.

The pretext that Donald Trump relied on to invade Venezuela seems to have shifted over time. The indictment that came out of the United States District Court’s Southern District of New York reads as follows: “Nicholas Maduro, the defendant, is at the forefront of that corruption and has partnered with his co-conspirators to use his illegally obtained authority and the institutions he corroded to transport thousands of tons of cocaine to the United States. Since his early days in the Venezuelan government, Maduro Moros has tarnished every public office he has held.”

I want to pause there. He’s allegedly running a narco state and facilitating the transportation and distribution of cocaine in the US. Then he is presiding over an illegitimate government that he had rigged elections. How much truth is there to any of that?

The main thing is, you can’t trust the US. They claimed that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction and they arranged an invasion in 2003 and went looking for them. They never found them and never really came to grips with that.

The New York Southern District Court began that indictment back in March 2000. So this is now nearly six years in which we’ve heard the allegation, but we haven’t seen any proof. We just saw a few dozen small speedboats being bombed, and 115 deaths on the same grounds. But no proof. We do know – and DEA statements confirm – that the fentanyl and cocaine isn’t coming from Venezuela. The cocaine is mostly from Colombia, fentanyl from China.

Trump says that they’re killing 300,000 Americans a year and that’s the justification for self-defense, and therefore not needing to go to Congress to approve this attack. But I think when all’s said and done, these claims have no evidence and from what we’ve heard Maduro just hasn’t the history of such drug trafficking.

The other big question: is Maduro’s 2024 electoral victory genuine? And if it’s not (and I would say it probably wasn’t) – he hasn’t released the votes properly – then do you just kidnap him? Obviously not. Even if you disagree with Maduro, I think that’s the position that most people take.

Is he a dictator?

I think so. He inherited the Chavista tradition, which was a genuine left popular tradition, maybe you could say a benign dictatorship. I witnessed him there, and met him, and found that this was a very popular effort.

I think Maduro lost a lot of that popularity over time, and he then partly imposed neoliberal – that is more pro-corporate – policies over the period. So there became a left opposition to Maduro. But certainly all of the leftists that I’ve known, and I’ve tapped into their statements, are against this US invasion. I think that’s a crucial point.

Sovereignty is absolutely critical here, no matter whether Maduro was someone who played all sorts of games with his own society, and stole that election.

The other crucial thing is that Donald Trump is really doing this for the oil. I think that point can never be underestimated. That was the same for Iraq in 2003. It’s always the question, what does the US military-industrial complex – and now Trump’s very good friends in the oil companies – get out of it?

America will effectively now be selling oil to the rest of the world that it does not own. It will reap the economic benefit of selling this oil to the people that are already buying oil from Venezuela. This is a point of inflection in the moral question of the international order that Russia, China, Brazil and all these countries will have to face. Do we support an American imperialist industrial military complex system where they’re allowed to sell oil that they ultimately do not own? And if they answer that question in the positive, it means that they embolden and empower the US. But if they answer that question negatively, it means that they have to stand up to the US. Which way is that scale likely to tip?

It’s so vital to think about what you could do, as a backlash against US power. For example, Tesla and X, both owned by Elon Musk, have been subject to boycotts. And that means our homeboy Elon Musk lost a quarter of his net worth in the first few months of 2025 when he was deep in this administration. Could one do that more generally? Could one have boycotts against Trump and his full set of operations? Many of the countries we’ve seen are scared, and they’ve been divided and conquered over the past year.

But I think the basic question for oil is what happens if Trump says Okay, there’s about 800,000 barrels a day coming from Venezuela – and he wants to increase that. The Saudis are about 6 million barrels a day. The US has about 4 million. The Chinese have been buying much of that oil. Would they say, “no, we’re not going to be dealing with the stolen property”? This remains to be seen.

I suspect that they may find that they can get their oil elsewhere in the world markets. Iran still has a very strong supply of oil also that goes to China, particularly because Russia still has big surpluses. So there might be some way in which we see a sort of configuration of the West maybe against the BRICS axis. Thus far, they’ve actually worked relatively well together: imperial power and subimperial connectivity.

But that may change because of the extraordinary arrogance of Donald Trump. Especially if he goes further – Cuba, Nicaragua, Colombia, Panama, maybe Greenland – and he does consolidate a sort of western hemispheric power. That’s an invitation to China invading Taiwan, and Russia continuing to expand its borders.

There’s an interesting response from the French government, which says: “The military operation that led to the capture of Nicholas Maduro violates the principle of not resorting to force that underpins international law. France reiterates that no lasting political solution can be imposed from the outside and that only sovereign people can decide their future”.

They are perhaps the first western nation to outrightly condemn the US here. But it’s also interesting to note France has oil interests in Mozambique, potentially South Africa if what’s happening in the Orange Basin goes ahead to an extent, and Angola. But very importantly, in Guyana, a neighbor of Venezuela. Is this the sort of response you would have expected from the French nation? And would they potentially be a lot more emboldened to support Venezuela?

There’s always a temptation, especially if you’re European, especially if you’re French, to condemn the Yankees. That’s easy. In fact, they did so in the Iraq invasion. Not only the French: the Germans as well. They were against Bush and Blair, at the time, invading Iraq in 2003. But they didn’t do anything.

Indeed we’ve seen Trump demand that the NATO powers – especially Germany and Britain and France – increase their spending, to up to 5% of their GDP, on military. And the way things are going, unfortunately, these are fairly weak governments in Europe and they’re probably going to go along with it. They may, you know, bark a little bit. But Trump will pet them and they’ll do what he wants.

This is a shortened transcript of two interviews given to SABC News, lightly edited for clarity. You can view them hereand here.