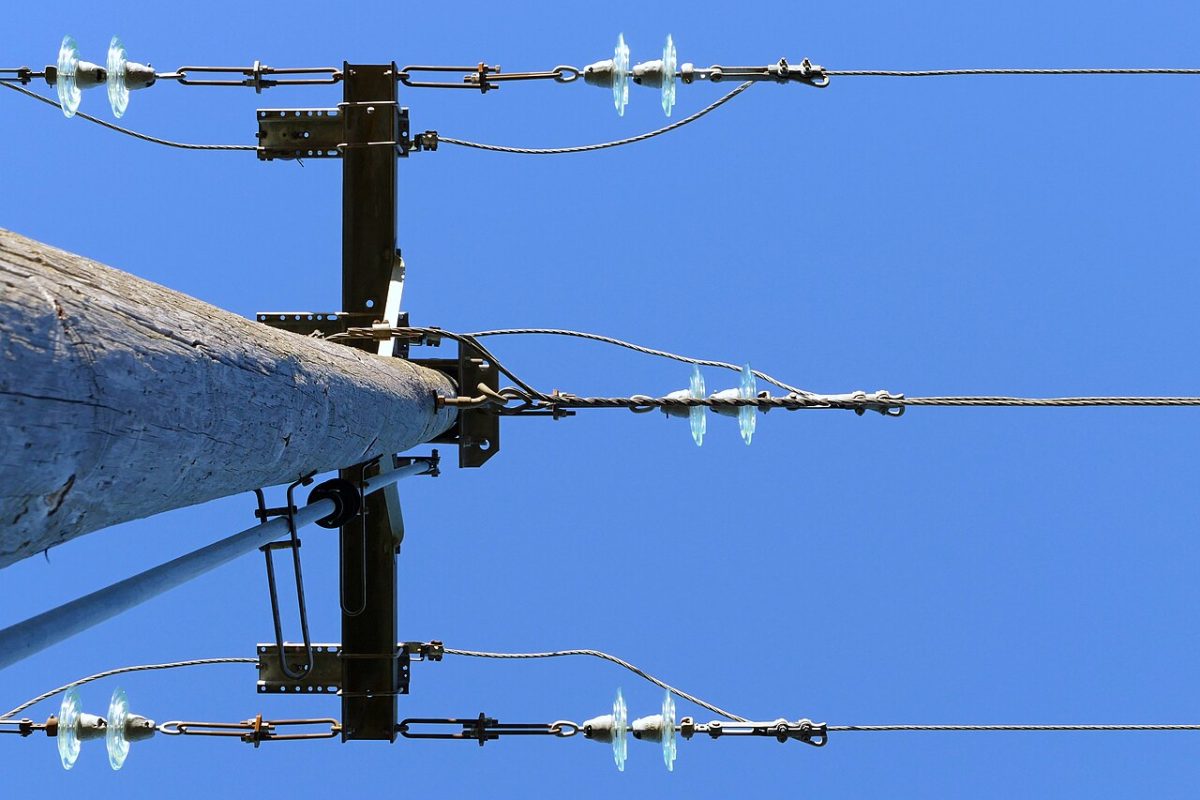

Consider two recent incidents in Germany. The first was on 3rd January, when a fire broke out in Lichtenfelde, Berlin. Even the British Guardian reported it: “German leftwing militants protesting over the climate crisis and AI have claimed responsibility for an arson attack that cut power to tens of thousands of households in Berlin”, and “In a 2,500-word pamphlet seen by the Guardian which a police spokesperson called ‘credible’, the group said it had aimed to ‘cut the juice to the ruling class’.”

Right wing politicians and media reacted hysterically. Berlin mayor Kai Wegner (CDU), who couldn’t break off from a tennis game to visit the victims, told die Welt: “we have been struck by a left wing terrorist attack”, and “left wing extremism is at the moment a high threat to Berlin. Left extreme terror is back in Germany”. Meanwhile CSU Leader Markus Söder said: “left wing terrorism is back stronger than we could imagine, and with fundamental implications.”

Three days later, the Linke Party leaders Ines Schwerdtner and Jan van Aken issued a statement on another incident – “An attack on one of us is an attack on us all.” The statement starts: “We are deeply concerned to see that some of our comrades are currently being massively attacked and in some cases subjected to full-blown campaigns.” It goes on to strongly imply that the Left was responsible for an arson attack on Brandenburg’s antisemitism ‘Tsar’ Andreas Büttner (a Linke member and friend of Israel).

Schwerdtner and van Aken’s statement argued: “Solidarity means engaging in debate with one another – without violence, intimidation, denigration, or insults. Instead, it means using words that strive for understanding. Even if we may hold a different position on the issue, it is our collective responsibility to reject these attacks, wherever and whenever they occur.”

What should the Left say?

Two stories of apparent “left wing terror.” One was criticised by the Right, the other by left wing leaders. Just what is going on here, and how should the radical Left react? One reaction would be to say that the Left has always criticised individual acts of terror. Lenin argued strongly with his brother, who was a Narodnik and attempted to assassinate the Tsar in 1887.

Trotsky wrote an article “Why Marxists Oppose Individual Terrorism” in which he argued: “the killing of an employer, a threat to set fire to a factory or a death threat to its owner, an assassination attempt, with revolver in hand, against a government minister—all these are terrorist acts in the full and authentic sense. However, anyone who has an idea of the true nature of international Social Democracy [ie socialists like Trotsky] ought to know that it has always opposed this kind of terrorism and does so in the most irreconcilable way.”

This opposition to individual terrorism is strategic, not moralistic. To gain our aims, we need a mass movement, not individuals acting on our behalf. By the very nature of their acts, terrorists need to hide their identity and are cut off from the people they want to represent. Having said all this, I think something else is going on here. A lot of people are jumping to conclusions and finding explanations which suit their political project.

It was the Vulkangruppe, which claimed responsibility for the Lichterfelde arson attack. Nathaniel Flakin has already argued on this website: “Was this a left-wing group? As of yet, Berlin police have presented zero evidence … While the statement uses phrases from the German autonomist scene, we know that Germany’s Federal Criminal Police Office (BKA) has written and published texts just like this.”

Nathaniel went on to argue: “If it is indeed a left-wing group, it is just as astounding that they have no periphery at all—not a single left-wing sympathizer defending their actions.” To recap, there is absolutely no evidence that the Vulkangruppe is left wing at all, and even if it is, on the Left scene it represents no-one but itself.

The case of a demonstration in Leipzig and Jule Nagel

Let’s now look more closely at the claims made by Schwerdtner and van Aken. Here, in their attempt to prove their claim that political opponents on the Left refuse to enter a political discussion, they appear to be conflating three different cases. Let’s look at them in turn.

They first raise the case of Jule Nagel, parliamentary representative for die Linke in Saxony. They say they are appalled that the group Handala “discredits the work of Jule under the motto ‘Antifa means Free Palestine’ and is calling for a demonstration on 17th January in the district of Connewitz. The focus is on Jule and also the project LinXXnet and the youth centre Conne Island in Leipzig”.

The demonstration was called after a number of recorded attacks on Palestinians and their supporters in Connewitz by so-called Antideutsche. The call to the demonstration states: “in Conne Island, in linXXnet and in the streets of the districts, US flags celebrated the bombs which imperialism dropped on Iraq and Afghanistan which turned the population into refugees. Israel flags were omnipresent on demos”.

Jule Nagel also has a long history of support for Israel. Because she is not the main focus of this article, I’ll restrict myself to this forensic article by Jüdisch-Israelischer Dissens Leipzig (Jewish Israeli Dissense Leipzig, JID) on the inconsistencies of her thought process.

The case of Bodo Ramelow

The second case which has given Schwerdtner and van Aken so much grief is the “massive hounding” of Bodo Ramelow. the Vice President of die Linke and former president of Thüringen. This hounding, they claim, consists of “put-downs, insults, and downright lies”.

For anyone who is unaware of Ramelow’s body of work, here are some of his Greatest Hits. When he was Thüringen president, he was deporter-in-chief. He campaigned for faster deportation procedures. Already in 2016, Fascist AfD MP Beatrix von Storch celebrated Ramelow’s attacks on migrants, tweeting: “Ramelow is right. Antifa has not understood democracy.”

That’s not all. When the president of the German parliament Julia Klöckner banned the queer rainbow flag from the Bundestag, Ramelow wrote an article saying “I stand behind Julia Klöckner’s decision”, in which he said that protests by MPs “weren’t necessary at all. Of course, we discussed her decisions in the executive committee, but she explained them very well, and we could all understand them.”

And then we come to Ramelow’s position on Palestine. In the debate on Klöckner, Ramelow said, unnecessarily: “The Bundestag can’t raise the flags of the demonstrating groups at every large demonstration in Berlin, since there’s a large demonstration here almost every week. She asked me if we should then raise the Palestinian flag at every pro-Palestinian demonstration in Neukölln in the future. I could only say no.”

This answer, at least, came as no surprise. On Nakba Day 2025, Ramelow celebrated “60 years of German-Israeli relationships.” In September of the same year, Ramelow dismissed talk of dead Palestinian children as “Hamas shit,” arguing that opposing the Israeli genocide was “on the way to saying” Nazi slogans like “Jews eat children.”

Die Linke should not be criticising demonstrations against Nagel and Ramelow – they should be actively supporting them. Any half-way left-wing party should make a clear stand against supporters of deportation and genocide, not make unconvincing arguments in their defence.

The case of a bomb attack on Andreas Büttner

And so we come to the bomb attack on Andreas Büttner. This attack has been formulated by Schwerdtner and van Aken as just another bullet point in a list. Schwerdtner and van Aken list three cases, Two of them are peaceful protests, the third an arson attack. The inference is that these events are equivalent and that anyone who supports one bears responsibility for them all.

But what is the evidence? That when Büttner’s Summer House was attacked, it was daubed with a red “Hamas triangle” – you know, the triangle which has been banned for alleged antisemitic content. Besides this circumstantial evidence, do we know that the people who attacked Büttner were Leftists, or indeed Hamas supporters? We do not.

We are back in the territory of the Vulkangruppe debate. Because politicians, and the media, have deemed it useful that this attack is the result of “left wing terrorism”, whatever that means, there is no need for any further investigations.

The Left has no need to defend Büttner who tweeted support for the Berlin police when they were attacking pro-Palestine demonstrators, and who believes that the Golan Heights are part of Israel. I, for one, understand the frustration of those watching Büttner’s political rise in a so-called “left” party – which is perfectly happy to accommodate his racism. But the accusations that we are to blame for any of the physical attacks against him are baseless.

What is die Linke leadership defending?

The statement from Schwerdtner and van Aken came on the very same day that The Left Berlin published an article which I wrote arguing “Schwerdtner’s change of heart [in which she apologised for previous mistakes made by the Party on Palestine] was the result of pressure from new members, who are serious about fighting for Palestine …. I fully support the newly formed BAG Palästinasolidarität, but here [in believing that the Party leadership has fundamentally changed its position on Palestine] I believe that they are being naive.”

Die Linke has tried to put itself at the front of a movement which it did not create. It is now trying to throw its members who built this movement under the bus. Just as it was quite prepared to expel Ramsy Kilani, it will do nothing against party members like Nagel, Ramelow, and Büttner, who vocally support imperialism and genocide.

This is not an article about political violence. Capitalism is a brutal system, and we may need to exercise some brutality to get rid of it. But here I am talking about the defamation of an entire movement with insinuations of violence, and an attempt to divide us between “good”, peaceful, demonstrators, and “bad” militants.

This divide and rule is a right wing strategy. We saw it recently when ICE forces murdered Renee Nicole Good in Minneapolis. Despite widespread video evidence to the contrary, Department of Homeland Security spokesperson Tricia McLaughlin tweeted: “rioters began blocking ICE officers and one of these violent rioters weaponized her vehicle, attempting to run over our law enforcement officers in an attempt to kill them—an act of domestic terrorism.”

As the state resorts to increasingly violent methods to maintain control (we only need to think of the violent policing of recent Palestine demos in Berlin), it increasingly tries to shift the blame onto someone else. The question is whether we oppose them or deploy the same tactics.

We should keep this in mind when we witness Schwerdtener’s and Van Aken’s hand wringing. It is not just the blatant hypocrisy of supporters of genocide suddenly discovering that violence is bad. By contributing to the myth of left wing terror, they strengthen the ability of the state to impose further repression. The Left deserves better than that.