Today, Hitler symbolises absolute evil: evil without moral restraint, a force capable of perpetrating the most unthinkable crimes, and which can only be defeated by brute force: war. Many politicians and leaders have been compared to Hitler. This comparator is recurrent when denouncing cruelty or authoritarianism. The idea that Putin is the new Hitler of our time has a special appeal and makes sense to many fed by the Western propaganda machine. This identification is with absolute evil. Another great ‘teaching’ from the indoctrination industry of Hollywood: evil is not negotiated with, it is fought. This is the hegemonic narrative that we hear repeated daily in the Western media, supposedly to justify excessive militarism in Europe.

The brainwashing machine of the Western press feeds this idea that we live in a world of heroes and villains. They decide who the villains are and who the heroes. And from this perspective, the ‘West’ and its political leaders are the good guys in this story. And mind you, they are not just ‘good guys’ and ‘well-intentioned’, but ‘heroes’ – who oppose the real-world villains represented by „autocrats“ and dictators, such as Putin, Maduro, and Xi Jinping. We can definitely discuss how democratic the societies are in which these leaders rule. Still, this tendency to permanently recall the evil that drives those leaders is like equating reality with a fantasy. It is another sign of the infantilisation of Western politics, which paints a picture of good versus evil, like a Hollywood script. In this script, interests do not drive international politics; there are no nuances, no grey areas. The evil leaders want to destroy the Europeans who so vigorously defend morality and human rights in the world. It is heroic Europe that defends itself against the Russian invader, or so they claim.

Upholding the idea of absolute evil represented by Putin and the leaders of the „other side“ goes hand in hand with the supposed moral superiority of the West. Similarly, militarisation, surveillance, and repression against the internal enemy are justified and necessary to control forces threatening European integrity.

One side note, the idea of evil represented in a person or group of people is a fantasy, or at least a distorted projection (See Hannah Arendt’s banality of evil). In analysing the Nazi bureaucracy, Arendt showed that this banality and cruelty are expressed in less spectacular ways. Cruelty becomes part of everyday life, in the bureaucratisation of crime, and the routinisation of murder. The Nazis perfectly embodied this type of regime. It was not so necessary for its officials to fiercely hate Jews (or anyone they considered ‘worthless’). Instead, they had to perform their duties well, follow orders, and demonstrate obedience to the system. Crime is not only driven by hatred, but by obedience and silent complicity.

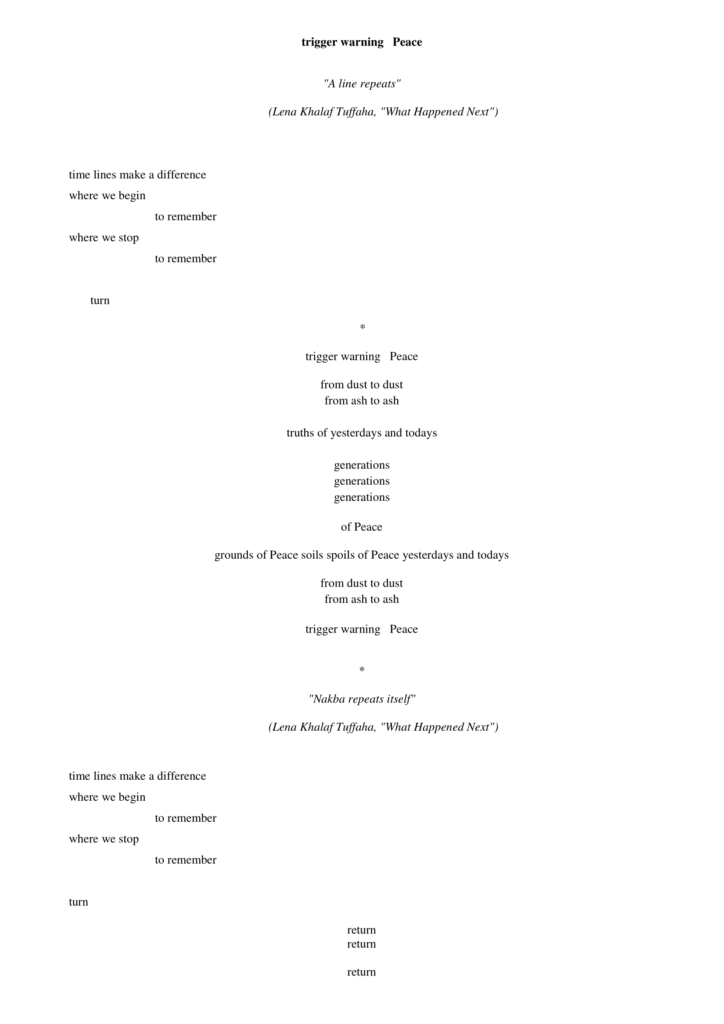

In an irony of history today, the trivialisation of evil, the systematisation of crime, and the routinisation of murder are unambiguously expressed in Israel’s genocidal policies against the Palestinian population. Israeli State terror is expressed in its rampant army that exposes its crimes on social media; in its legal system that maintains apartheid and surveillance in the occupied Palestinian territories; in the legalisation of violence and rape against Palestinian prisoners; in the fanatical settlers who attack Palestinians in the West Bank daily. All these and many other examples show the routinisation of state-led violence. Without a doubt, fascism reigns in that country and is accepted by a large part of its population. It is, they say, a necessary path to ‘resolve’ the Palestinian question and build ‘Greater Israel’.

But the „evil“ that the Western ‘free world’ is fighting is Putin. Meanwhile, Netanyahu is assured impunity. This is typical Western hypocrisy, to which we are sadly accustomed. Despite the apparent brutality of the Israeli regime, Western elites have done their utmost to ignore the genocide in Gaza, while presenting leaders like Putin as the absolute evil.

But this narrative in the West presents problems. Where does Donald Trump fit in? The liberal progressive view is that he is considered a dangerous ally of these ‘other’ autocratic leaders. His attempts to end this conflict may have momentarily saved Europe from a major conflagration with Russia (doomsday clock). Trump’s decision to dismantling USAID shows one big difference between Democrats and Republicans when it comes to the projection of imperial power. Trump reveals the true face of a decadent, indebted, and financialised empire that has opted for threats, brute force, and military force as a method of negotiation and persuasion. The best example of this shift is the just-released National Security Strategy, which outlines new pathways to global hegemony and a renewed Monroe Doctrine.

Europe, clings to the kind of soft power that Trump wiped out in one fell swoop. European leaders have never had any problems with the imperialist policies of their great master. They were willing to go to war in the name of ‘freedom’ and ‘democracy’, with a few exceptions such as Iraq. Europe has been a trustworthy partner for US hegemony. Europe’s eagerness for war, not only makes it indistinguishable from the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) but also ensures the continuity of its position as a loyal subject of the empire. European leaders are confused and resent having lost their great ally. While Trump shows his true face as the ‘great master,’ relentless and cruel to his allies and lackeys. In fact, Trump and his administration’s contempt for Europe is undeniable.

But Europe could still save itself if it chose more wisely with whom to ally in this new multipolar order. Perhaps now is the time to rethink its relationship with the master and pursue its own goals. Those may not necessarily align with Washington’s interests, but do align with those of its own citizens. Perhaps a little rebellion against ‘Daddy’ Trump would even restore some dignity to this bunch of obedient children.

But Europe remains stubbornly stuck in its fantasy world. Instead of learning the lesson that, in geopolitics, it’s all about interests — and not morality, as the Germans love to think — they prefer to portray Trump as an idiot manipulated by the superior intelligence of Putin and Xi. But despite their criticism of Trump for his attempts to end the war in Ukraine, they remain obedient buyers of everything the American military-industrial complex has to offer—new war toys for when Russia supposedly invades Europe in 2029.

Unmasking American cultural imperialism

The general public, especially in Europe, needs to understand how American cultural imperialism operates in the world. This colonisation of the mind is manifested in the crude distinctions between good and evil that permeate Western politics today, which requires the continued demonisation of Russia and China.

Meanwhile, the United States projects a heroic image of defending superior values as the German sociologist Bernd Hamm writes:

“The US has successfully managed to implant into the brains of perhaps the majority of human beings a self-portrait of brave heroes fighting fiercely for freedom, democracy, and the rule of law wherever there is a need to fight. Reality, however, cannot be further away from that. In fact, and certainly after the nuclear bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it has been the most ruthless, most egomaniacal, most brutal actor, the real rogue state.”

(Hamm, Cultural imperialism. 2005: p.20).

Cultural Imperialism is an expression of soft power. And we know and should have in mind all the images of heroism, kindness, and goodness that the empire projects through its propaganda machine while destroying whole societies in the name of “freedom” and “democracy”.

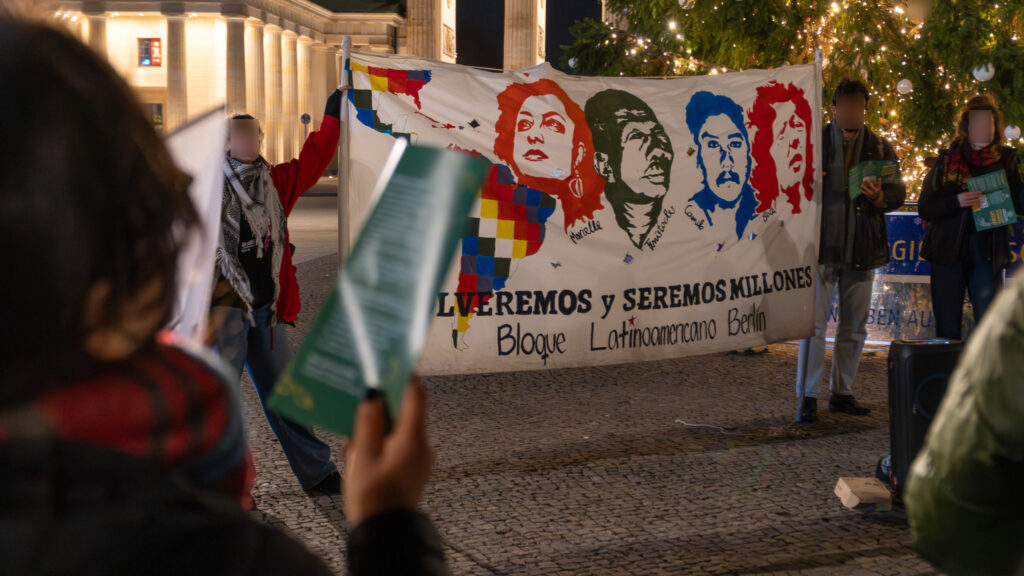

I write these lines from a Latin American standpoint, with only a minimum of historical memory, knowing what the empire has done in the past and what to expect from it. Latin America has always suffered intimidation, harassment, and attempts to destabilise its economies and provoke ‘regime changes’ – a euphemism for military coups followed by cruel dictatorships. For that, there will always be local leaders willing to do “that” job, pursuing the empire’s interests. Today’s ‘sons of bitches’ of the West, the Netanyahus, Al Jolani’s, Corina Machado’s, and Selenesky’s, will be protected by Washington and its allies until they are no longer of use to them.

In Europe, the brainwashing of the cultural imperialism industry also involves the complicity of its elites. This ensured them juicy profits when a new market was opened by force, at gunpoint. The entry of Chinese capital into Latin America has exasperated the European political elite. One effect of multipolarity seems to be that the so-called “developing” world no longer looks to Europe as its great example. In fact, many will ask themselves – What is wrong with Europeans? Have they not realised that the world has changed?

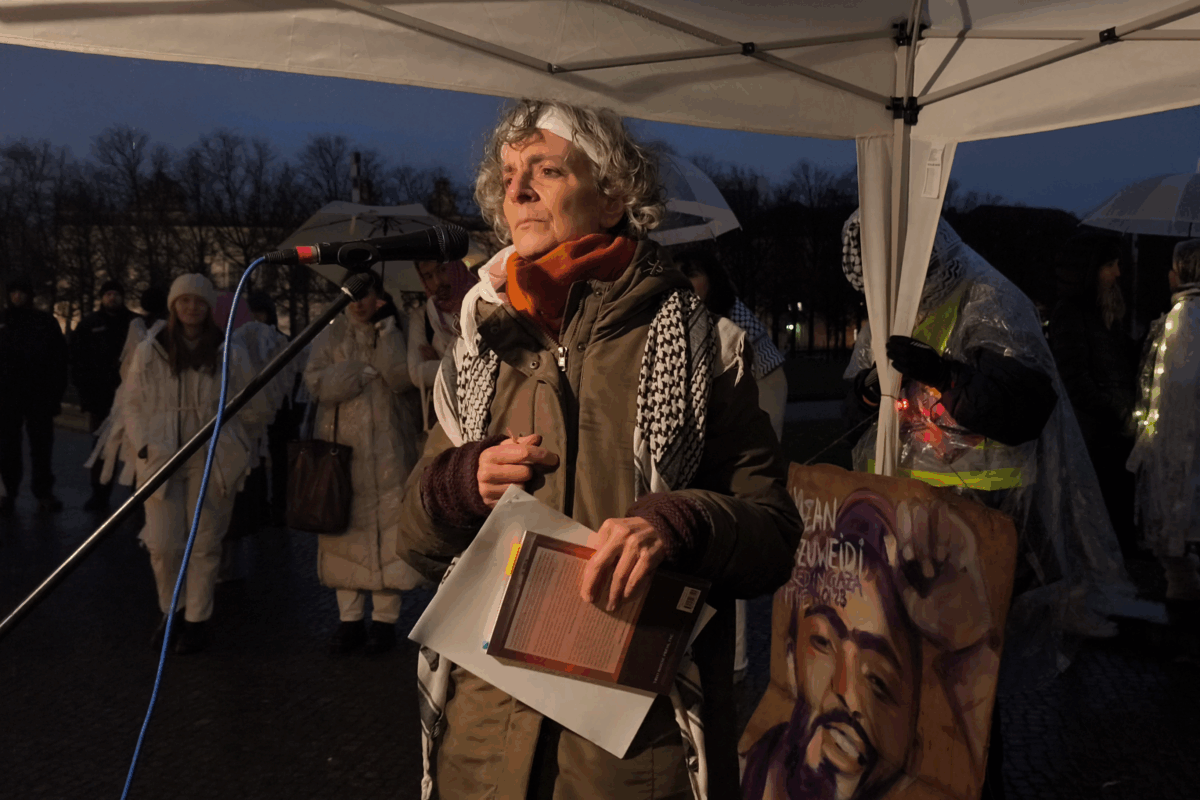

I know it is a little unfair to talk about “Europe” as a homogeneous bloc, as we must differentiate between the political elite and its citizens. Its political elite, which is desperately trying to drag Europe into another war, is very unpopular. At least in Germany, we slowly see public resistance to preparations for war. But given the intensity of NATO propaganda to lead Europe into a direct confrontation with Russia, it is not enough. Especially compared to other historical moments, such as the „eighties“, when the peace movement was strong and loud.

Within this propaganda war, politics goes hand in hand with the mainstream media. While in the West, the media claim to report ‘facts’ and ‘truth’, while accusing their enemies of the opposite. That is, the Russians and the Chinese spread misinformation, manipulate, distort, and lie. Supposedly, the Chinese feed us algorithms through TikTok that expose the crimes of the Israelis in Gaza and the West Bank, or show that Russia is winning the war. But we should ask why European leaders are so desperate to silence independent journalists, podcasters, and uncomfortable interviewers. Europe has a problem with the freedom of opinion it claims to uphold. There is a brutal contrast between what Social Media exposes and what the so-called Western media tells us. To control the narrative in the West, political powers seek to control digital platforms such as Telegram or TikTok. As these images do not align with the narrative being peddled in Europe, Brussels’ desperation to control it is already palpable (see the Chatcontrol project).

We must not forget that the goal of Western propaganda is to demonise and dehumanise the “enemy”. It seeks to prove that a war against Russia is necessary, even if it destroys Europe once again. To counter this, we must unmask these attempts to portray Russians as ‘barbarian hordes’, Chinese as the ‘growing eastern threat’, migrants as ‘eternal foreigners’, Palestinians as ‘the usual terrorists’, and the left as the ‘internal enemy’. Let’s begin by not falling into that trap.