As the genocide in Gaza rages on, Israel’s ultra-right government is using the chaos of war to further entrench the apartheid regime both in Israel proper and in the Occupied Palestinian Territory. Since October 2023, more than 30 new laws have been passed that deeply infringe on fundamental rights, criminalise Palestinian life, and shift Israel’s legal order decisively toward an authoritarian ethnonationalist regime.

Over the past two years, the extremist Netanyahu government has dramatically expanded the institutionalised apartheid against the Palestinian people. From October 2023 to July 2025, the Knesset passed more than 30 laws targeting the basic freedoms of Palestinians and subjecting millions to collective punishment. This is the conclusion of a new report published by the Israeli human-rights organisation Adalah, which focuses on legal protection for Palestinians. The “cumulative effect” of this flood of racist laws is “to further entrench and deepen Israel’s regime of apartheid and repression over all Palestinians under its control—both in Israel and in the Occupied Palestinian Territory”, Adalah writes.

Collective punishment: Deportations by ministerial decree

This barrage of racist and discriminatory laws joins dozens that came before it, through which successive governments since the founding of the state have degraded Palestinians to second-, third- and fourth-class citizens—now numbering over 100 in total. The cluster of apartheid laws rushed through since the start of the genocide covers a wide range of political and social domains. “Beyond criminalizing legitimate political, social, and cultural expression,” Adalah writes, the new laws authorise the state to carry out streamlined deportations, further restrict Palestinian marriages or family reunifications, withdraw funding from schools, cut social-security benefits, lower the threshold for detentions, and restrict access to critical media.

The “Deportation of Families of Terrorists Law”, passed in November 2024, allows the government to deport family members of persons deemed “terrorists” by the state—even if they are merely suspected of “terrorism”. Such deportation orders can remain in place for decades. It is obvious that the principle of individual culpability, fundamental to any bourgeois legal system, is being replaced by the concept of collective guilt: what matters is not a person’s own actions but who their family are. And it is not the courts—already under political fire—that decide, but the interior minister by a mere administrative decree: an increasing concentration of executive powers as befits an increasingly authoritarian state. During the reading of the bill, it was made explicitly clear that no one should assume that the families of Jewish “terrorists” would ever be targeted—for example, the relatives of the fascist who murdered Yitzhak Rabin: No, this criminal deportation law applies exclusively to Palestinians.

Orwell’s thought police

Freedom of expression and press freedom—already severely eroded—have been further mutilated: “The only democracy in the Middle East” now draws freely from Orwell’s thought police. A new law criminalises the “denial of the events of October 7, 2023”. Yet, to this day, the Netanyahu government refuses to appoint an official commission of inquiry or publish an “official narrative” of the events of that day, Adalah notes. The far-right government also blocks a UN investigation into allegations of sexualised violence allegedly committed by Hamas and other groups on that day. More than two years after the attack, it remains unclear to what extent the Israeli military implemented the “Hannibal Directive” on October 7—and thus how many of the deaths that day were caused by Israeli forces deliberately bombing their own people to prevent their capture.

The law criminalises a vague “denial” without clarifying what the object of this denial even is—arbitrariness and abuse are built in by design. “The law is designed to cultivate fear, stifle public debate, and suppress discussion on a matter of public concern,” Adalah concludes. Mere expressions of opinion or questioning of the executive’s nebulous narratives are criminalised. A special task force imprisoned hundreds of Palestinians inside Israel in the first weeks after the attacks for “likes” and posts on social media.

Shielding the public from reality

Another extremely dangerous law criminalises the consumption of certain media that the Israeli state dislikes. Anyone who indulges in the “systematic and continuous consumption of publications of a terrorist organization” faces up to one year in prison. Such consumption, the law claims, may “create a process of indoctrination—a form of self-inflicted ‘brainwashing’”, ultimately increasing “the desire and motivation to commit an act of terror to a very high level of readiness”. Again, everything is deliberately left vague, nothing is specified, leaving room for anything—and everything.

It is obvious that the targets here are not the fascists and demagogues on Channel 14—the home channel of Netanyahu’s Likud party—or other genocide-aligned outlets in the Israeli media landscape. It is Al Jazeera and similar platforms, which show a more realistic picture of the often-indescribable crimes committed by their government to those who are willing to see, and which have already been heavily criminalised. In May 2024, all Al Jazeera operations were banned inside Israel, and even their reporting in the occupied territories was prohibited. Netanyahu thus aligns himself squarely with notorious despots, mass murderers, and war criminals such as Egypt’s torturer-in-chief el-Sisi, Saudi Arabia’s butcher MbS, or his Emirati partner-in-crime MbZ. Under the current circumstances, the government is aggressively attempting to extend the Al Jazeera ban to other international media organisations; even the Israeli liberal daily Haaretz is being attacked wherever possible.

Multi-front war: Palestinians as targets

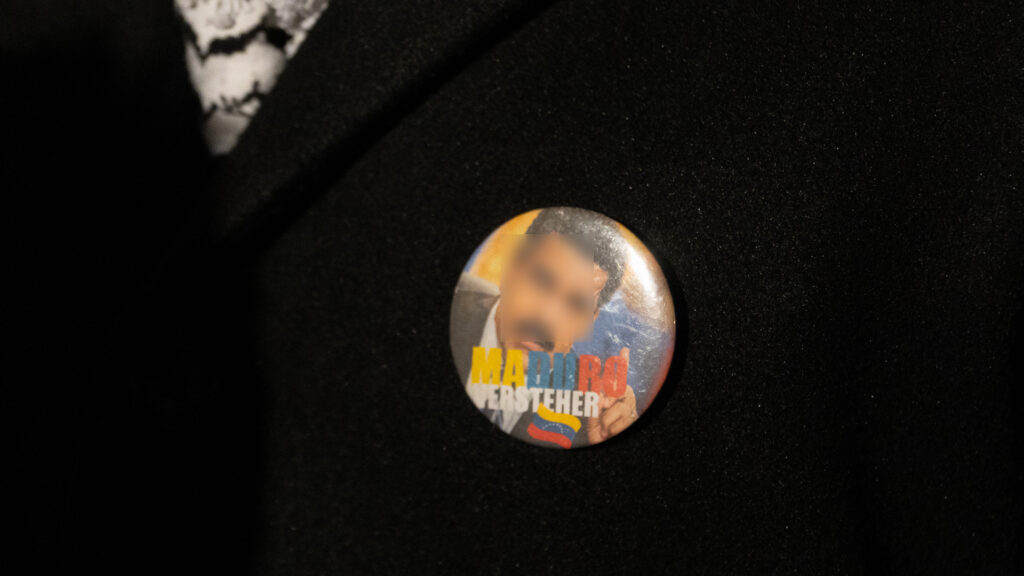

Other aspects of the more than 30 new apartheid laws include, among others, the intensification of discriminatory allocation of state resources and social benefits, the systematic denial of fair trials, violations of prisoners’ rights, and the firing of teachers or the defunding of Arab schools on the grounds of their alleged “terror support”. In November, the Knesset passed a first reading of a bill introducing the death penalty exclusively for Palestinians. The fascist Israeli police minister Itamar Ben-Gvir appeared at a committee meeting on this bill wearing a pin on his lapel—a modified version of the yellow ribbon for the hostages: in this case, showcasing a yellow noose. “A legal system organized along ethnic lines that denies fundamental rights to a racial group constitutes a crime under the 1973 Apartheid Convention,” Adalah concludes soberly. With the recent wave of apartheid legislation, “the Knesset has and continues to ingrain recognition of Jewish citizens as the sole collective entitled to the full spectrum of individual and collective rights, and to further codify in Israeli law a regime of Jewish ethno-national supremacy”.

Since the ultra-right government took office in December 2022—a coalition that includes self-described fascists—everyday anti-Palestinian racism in Israeli society has exploded, fuelled and encouraged by the government itself. The escalating discrimination against Palestinians has also served to unite deeply fractured political parties: several of the new apartheid laws were passed with the support of opposition parties.

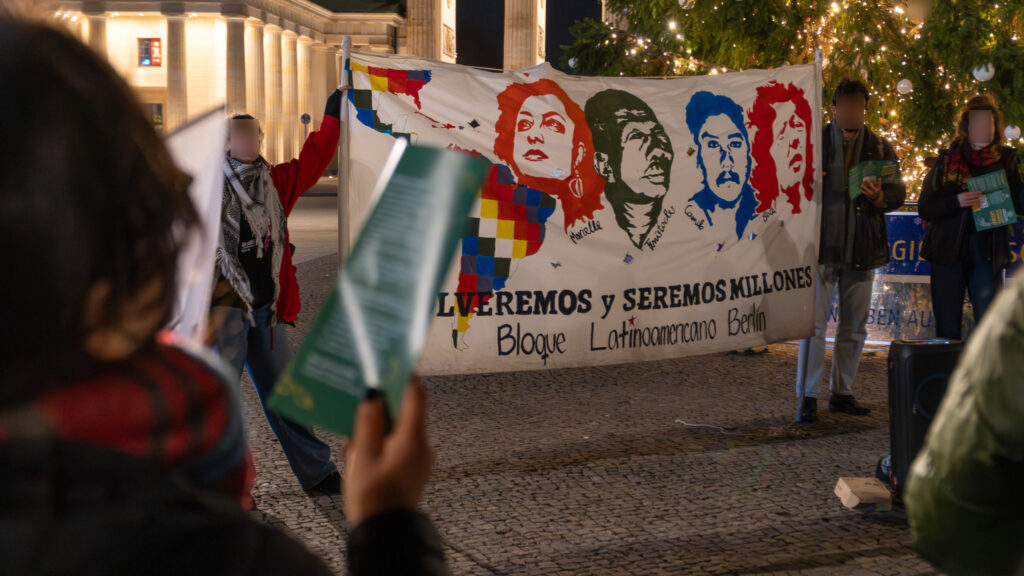

Israel is waging a multi-front war against Palestinians with tailor-made weapons for each front: In Gaza, the population is being physically annihilated by means of genocide. In the West Bank, containment, displacement, disenfranchisement, and apartheid are the tools of choice, in close collaboration with settler fascists whose pogroms and raids contribute to ethnic cleansing. Inside Israel-proper, the fight, by now, largely takes the form of lawfare—the political weaponisation of the bourgeois legal system. The fourth front is outsourced territorially and is gratefully embraced by Israel’s allied right-wing governments in the West, above all in the USA, Germany, the United Kingdom, and France. They use the opportunity to sharpen their own authoritarian profiles, attacking Palestinians in the diaspora with batons, tear gas, and prison cells.

Emboldened, equipped, and shielded by its last allies—collaborators—in the West, the Israeli state is escalating its brutal violence against Palestinians on all fronts. What remains is an utterly unrestrained government whose frenzy against an enemy marked for destruction pushes the boundaries of the conceivable every single day.