Thanks for talking to us. Could you start by introducing yourself?

I’m an activist who is involved in the Berlin group of the Shut Elbit Down campaign. Elbit Systems is the largest private Israeli arms manufacturer, a company that boasts of enabling the Israeli Occupation Forces (IOF) to carry out all of its war crimes and genocidal actions in Gaza, Occupied Palestine.

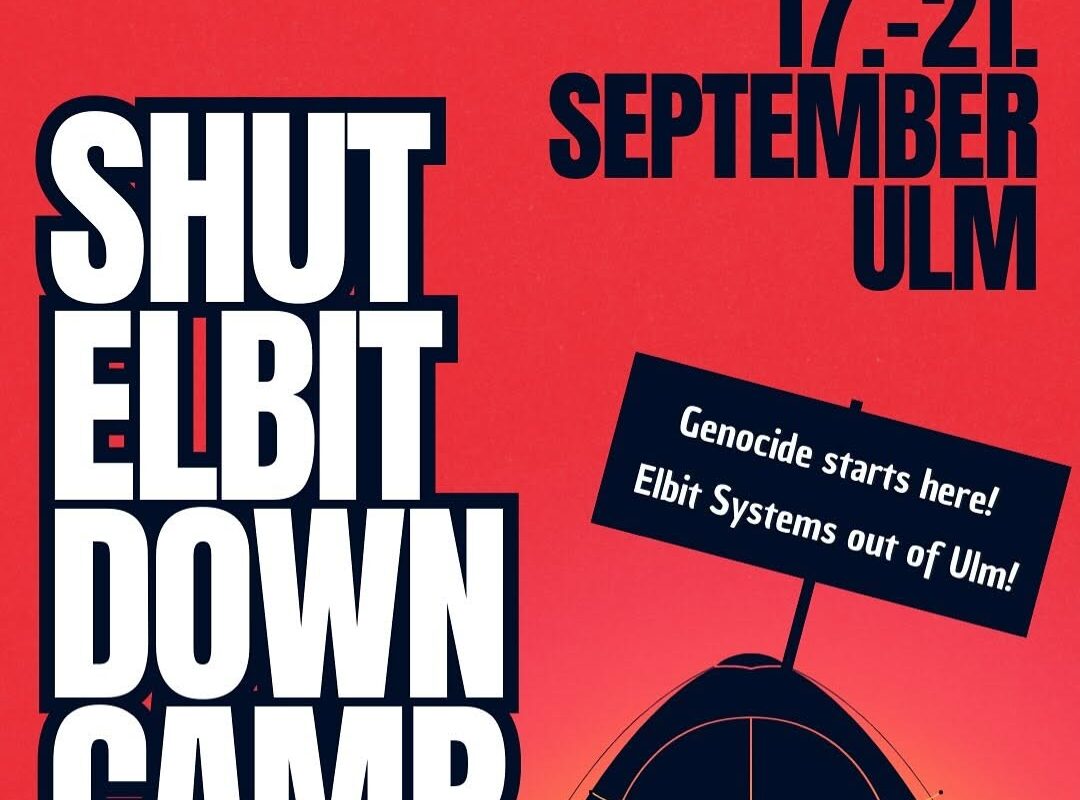

Shut Elbit Down is a global campaign, active in countries all around the world. In Germany, we’re also active in Frankfurt, Munich and in Ulm, campaigning and taking action to shut down Elbit offices in Berlin and Koblenz, as well as their production site and office in Ulm.

How big is the Berlin branch, and what have you been doing?

I would say it’s pretty sizable, we have members from across the political spectrum and a wide variety of backgrounds. We’ve been organizing rallies and info-stands outside Elbit’s office. We organized a fundraiser recently. We’re currently about to launch our camp in Ulm to protest outside the largest Elbit offices in Europe. That is our main focus right now.

We have also organised an E-Mail template for an Anzeige – a criminal complaint – that members of the public can file. You can file this legal complaint against the mayor of Ulm via E-mail for allowing this genocidal company to be present in the city from our linktree. It takes less than a minute, the text is prewritten, you just need to enter your personal details to file the complaint.

We also have a petition to evict Elbit from their office in Berlin. It also takes just a few seconds and helps us build pressure against this genocidal company on yet another front.

Additionally, we have also drafted an E-mail template to the security company who guards Elbit’s office. Pressure on them can really damage the security situation for Elbit Systems Germany – security they do not deserve to have while the people of Gaza endure endless suffering.

These digital actions, that really can be done by anybody, help us apply pressure on the companies and individuals who’s complicity enables genocide to be produced in Germany and sent to Palestine.

Do these Anzeigen have to be in German, or can people write in English as well?

The prewritten templates are in German, but they can be sent by anybody if they just fill in the empty fields with their personal details.

Could you explain a bit more specifically what the problem is with Elbit?

Elbit Systems is a company that prides itself on enabling war, suffering, and the general destabilization of the world through war. They manufacture drones and other military technologies that are used in Gaza. We know that approximately 20% of all of the military components and weapons that they produce in Germany are used in Gaza to commit atrocities that words cannot describe.

They’re also complicit in human rights violations all around the world. They make the technology that enables the militarisation of the US-Mexico border, where we know there is a huge variety of human rights abuses taking place. They also armed the Turkish state in the past, as well as the Indian state, and the Moroccan state, which directly enables these countries to violently occupy Kurdistan, the Western Sahara and Kashmir.

There is a huge, broad range of human rights violations in which Elbit is beyond complicit. We are focused on the genocide in Gaza, however Elbit’s involvement in these other human abuses show that our struggles are connected. That is what has brought us here. We see the unity between all antiimperialistic struggles, and that Elbit is arming multiple authoritarian regimes around the world, upholding the systems of imperialism and colonialism.

Elbit makes weapons intended to kill, to maim, and to traumatize. They make drones that can drop explosives on hospitals, nurseries, and refugee camps. The drone is unmanned as explosives are dropped, adding to the dystopic nature of modern warfare they enable. This has led to whole battalions of IOF soldiers who play with these remote aircraft like toys as they unleash terror on the captive Palestinian population in Gaza. The drones can play sounds of pregnant women begging for food or babies crying in distress, baiting victims, exploiting the humanity of those who are targeted and killed, tricked by cries for help.

These are incomprehensible levels of direct complicity from Elbit Systems. Producing these murderous technologies is something upon which Elbit prides itself, and we see that as intolerable genocidal terrorism.

We are showing that this isn’t just us who find this unacceptable, we are many, prodominantly in our communities in Berlin and in Ulm, who are resisting the fact that their neighbours are producing genocide. This is beyond complicity. It Is the direct empowerment of genocide.

Do you see a potential danger that concentrating on Elbit leaves other arms manufacturers like Rheinmetall off the hook?

I think that right now Rheinmetall is also really in the spotlight due to the amazing direct actions and large-scale protests of Rheinmetall Entwaffnen in Cologne.

I do think that it’s most important that we focus on our targets. There are so many companies whose profits are soaked in the blood of the Palestinians – as well as the people of Congo, Sudan, Yemen, and so many more. If we focus on all of them, it gets very difficult to be effective.

The more you target one specific company, the more you can make that one company lose lots of money. We can see that in the UK where four of Elbit’s six factories have been closed down, causing severe financial losses and irreparable damage to their reputation. We know that targeting Elbit works, we know that we can and we will shut Elbit down.

Protesting against every weapons manufacturer dilutes the cause, as it spreads our capacities more thinly, I would argue. We believe that targeting Elbit specifically is really important, the same way that Rheinmetall is a specific target of the Rheinmetall Entwaffnen campaign, neither they or we are losing focus.

The closure of the Bristol factory happened just weeks ago. What was it that led to this?

We know that we can create a lot of change, but often it doesn’t happen as quickly as we want it. In Bristol, it was years of prolonged action, both protests and property destruction, that led to this victory. People broke into the factories. Israeli dissidents, who are still yet to have their trial, flew in from Germany and Portugal, and took action in England. This is how we know that when our solidarity goes beyond borders, we can really hit Elbit where it hurts.

This involved property damage, and serious protests, but it was also the support of the community. It was people joining protests outside occupied factories, especially in Leicester. We know that it is prolonged and steadily maintained action that allows us to shut these companies down.

It is about staying targeted and very focused, as Palestine Action UK were in Bristol. In the end, a broad range of protest tactics made it too expensive for Elbit to keep this site open. It affected their profitability. So they decided that it wasn’t financially viable for them to manufacture genocide from Bristol.

That is what is going to happen to all of their other sites in Germany. We know that it’s going to happen. It’s a matter of time, because the movement is growing. People don’t want genocidal neighbours. People don’t want their colleagues or people they share buildings with to be producing arms to be used in genocide.

In Britain, Palestine Action has just been banned and the government says that it is as dangerous as the Islamic State for very similar actions to the ones you just described. Do you think that this is going to put more pressure on Shut Elbit Down, either in the UK or here in Germany?

I can only talk about our campaign against Elbit in Germany, we will not bow to any pressure like that. We do not fear the repression of the German State. The Shut Elbit campaign does not endorse property damage or illegalactivity.

We understand that the campaign exists on a broad spectrum when it comes to legality, and Shut Elbit Down works without destroying property, as Palestine Action are alleged to have done. But we understand that there are a huge range of actions that can and likely will be taken by other autonomous groups. In the case of this genocide being live-streamed straight from Palestine to our phones, we know there millions of people globally who are becoming enraged to take action against the zionist war machine. We are one group in the campaign, other groups can carry out different types of action.

We all know that there are certain difficulties about organizing for Palestine in Germany. Do you think it’s possible for Shut Elbit Down to have the same effect in Germany that it has in Britain?

We acknowledge that the movement is younger in Germany. Palestine Action was founded in 2020, much before the recent escalation of the current genocide in Gaza. Shut Elbit Down was founded in December 2023, so we acknowledge that we are behind in that way.

Right now, Germany isn’t near the level of having pro-Palestinian groups proscribed to the terror watch lists, but we do see the increasing authoritarianism of the German government, whether it’s trying to ban the Rheinmetall Entwaffnen camp or attacking the camps protesters and kettling them for 12 hours in Cologne.

These different authoritarian techniques do not intimidate us at all. Whatever they do, we’ll come back even stronger. Solidarity is not terrorism. Resisting genocide is not terrorism. There’s no way that anybody who seriously critically engages with the media they consume can believe that red paint is terrorism, compared to actual terrorist attacks carried out by the Islamic State like the Ariana Grande Manchester concert bombing for instance.

I think there was a really serious disconnect here, and people are beginning to see it. People are seeing through the lies and the authoritarian tendencies to paint solidarity with Palestine as terrorism. It’s as old as colonialism itself. Portraying the oppressed as animalistic and uncivilized and terroristic isn’t working anymore. People see past that, and we will not be intimated.

What’s the relationship between what you’re doing and other actions for Palestine?

I think all of these actions help to progress the anti-militaristic and decolonial cause. We are in solidarity with Rheinmetall Entwaffnen. We were present at their camp, we stand in solidarity with each other. We’re fighting the same fight. We also know that we scare these companies. These companies have not experienced these levels of severe protests in a long time.

It is because we see what’s happening in countries across the global south. We see the apocalyptic scenes in Gaza. We see the immense trauma that people are experiencing, seemingly with no end. We know what we can do to take action and stop this imperialist machine, and we’re doing it.

Our camp on the 17th-21st September is being organised together with a plethora of groups. We won’t be divided, and we will be staying united for the liberation of Palestine, and for concrete policies like a weapons embargo on Israel by the German state, a policy we know that Germany will at some point have to implement. There is no escaping that.

Maybe you can explain a little bit more what’s going to be happening at your camp. Last week, there was the Rheinmetall Entwaffnen camp in Cologne, and now you’re organising something in Ulm?

I wasn’t present at Rheinmetall Entwaffnen camp myself, so I can’t say what direct similarities there might be. We have multiple events happening, including many cultural events. We have Dabke, clothes printing workshops, educational workshops about Elbit and the history of Palestine. We have other groups bringing their campaigns, where we can all work together.

We also have protests registered during the camp, protesting outside the office of the company we know that is driving the genocide. We’ll be bringing a wave of pro Palestinian sentiment into the city of Ulm to remind people they need to take a stand against their genocidal neighbours, and that every single person who stands up matters.

We are growing, and we are going to send a really strong message from Ulm to Elbit Systems, that they are not welcome in this city, and that nobody wants genocidal neighbours. Our camp will be directly outside the main Elbit office.

One of the difficulties of campaigns like Rheinmetall Entwaffnen is approaching workers in the factories who are worried about their jobs. Have you made any attempts to link up with people working for Elbit?

We’re still making those links. We are open for anybody to contact us and get involved. We haven’t had any large scale discussions with workers so far. We understand it’s very difficult to lead these discussions, but we are ready for that challenge.

But you do have contact with people living next door to the factory

Yes. We have already had contact with the neighbours. We’ve received communication from neighbours who stand in solidarity and the general public in Ulm. We felt a lot of support during demonstrations that have been going on against Elbit systems for over a year. We’ve been in the press countless times in Ulm, bringing the cause of Palestinian liberation to this small city in Baaden-Württemberg

The camp is going to be for five days. Most people reading this interview live in Berlin. How can they get to the camp?

We want this camp to be accessible to people Germany-wide, even beyond Germany. So we have a solidarity bus that is travelling on Wednesday 17th September from Berlin through Leipzig and Nuremberg to Ulm. There will also be a bus travelling from Freiburg, Karlsruhe and Stuttgart.

You can find more information on our Instagram in German and English. It’s also on our Telegram channel, which you can get through the linktree on our Instagram page. There is a recommended donation of €25 for the buses, but people who don’t have the financial ability to contribute are still more than welcome to join us. The buses return on Sunday 21st September . We want the buses to be as full as possible to justify the long journey.

We need to be taking serious action against Israeli arms manufacturers that are working within Germany. You can find out more about the protests on our social media. But we really need people to make a big decision and take a long trip down to the South of Germany to Ulm in Baden-Württemberg.

What about people who work or can’t make it to Ulm? What can they do?

Comrades in Berlin who were unable to travel will still be protesting against Elbit systems. If you would like to be involved in that, please DM us on Instagram.

Have you got any further actions already planned?

We’re still discussing. we know that as long as the violence continnues, we shall continue. There is not going to be a peaceful moment for Elbit systems as they continue to operate in Germany. They may think that Germany is a safe country for them to operate in due to the German State’s endorsement of the genocide in Gaza, but there is no way that they’re going to continue to fuel genocide from within our cities and towns in the long term. Their end is near.

And the camp provides an ideal opportunity to plan future actions?

Yes. Please come to the camp, and social events and networking events. We can further unite our causes through other anti-imperialist movements, against the occupation of Kashmir, Western Sahara, Kurdistan, or the militarized and US American Mexican border. We can and will take action to bring us closer to liberation.

Is there anything else you’d like to say is anything we’ve not covered?

Our linktree contains many digital actions for people to get involved. It can really make a difference if we overwhelm the mayor of Ulm with criminal complaints and we get thousands of people signing a petition to evict Elbit from their Berlin office.