A couple of years ago, Lost in Europe published an investigation revealing that tens of thousands of unaccompanied migrant children have disappeared from Europe’s records. Vanishing from official radars, their whereabouts became nearly impossible to trace, leaving ample cause for wild speculation.

In Germany, one of the four main countries cited in that report, the situation for many refugees has gotten worse, with an increasing amount being pushed into homelessness. This is starkly visible in the capital, where Berlin’s infamous open drug scene has become home for a large population of undocumented migrants. Hotspots like Görlitzer Park and the nearby Kottbusser Tor (”Kotti”) are among the most obvious examples.

It doesn’t take long when at Kotti to notice the surprisingly young age of the North African boys selling drugs in the area. They are not only young but lack any valid documents or legal status. For me, meeting them was a quick reminder of the missing youth documented by Lost in Europe.

Since asylum applications from North Africans are routinely rejected in the EU, many of these boys deliberately go off the grid to avoid deportation. And those who have accumulated criminal records (due to unpaid fines, or theft, or drug dealing) tend to disappear in order to avoid detention.

These boys are famously known in local dialects as Harraga, which literally means “burners” in reference to burning borders, burning passports, or even burning the past, leaving everything behind to seek what they thought would be their perfect future in Europe. Their dangerous migration journey was meticulously documented by German director Benjamin Rost, who spent years following a group of Moroccan boys heading to Europe for his documentary film titled Harraga.

The film shows boys between 13 and 19 years old attempting to cross land borders from Morocco. Some of them, along with countless others whose journeys go undocumented, reach Spain, where they eventually join other youth who crossed the Mediterranean from other parts of North Africa.

For the Harraga youth who do successfully reach Europe, they become street children in Spain until they apply for asylum. Driven by hope or necessity, some continue their journey to other EU destinations. By the time they reach a final destination like Berlin, they discover that having previously applied in another EU state subjects them to the Dublin Regulation. This leads to a rejected claim and a deportation order back to the first country of application. Additionally, a trail of unresolved criminal cases left behind in transit countries also contribute to the denial of their asylum requests.

All these legal hurdles are often followed by economic struggles due to severe lack of legitimate income sources. This gap is the primary reason for their high tendency to commit crimes. Even those who apply for asylum in a comparatively generous city like Berlin receive only 200-400 Euros in monthly from the state. Formal employment is structurally inaccessible. Most are either ineligible for a work permit or must first secure a job offer, a significant barrier, as many have left school early and some are even functionally illiterate. Even those with certificates find them unrecognized in the EU. These systemic obstacles are compounded by personal challenges like trauma, family separation, and substance abuse, making the sustained routine needed to learn, certify skills, or hold a job nearly impossible.

This reality leaves many with access only to informal labor, such as construction or kitchen work. The far more lucrative and flexible alternative is drug dealing. In Berlin and other German cities, this precarious situation has fueled a sharp rise in the number of Arab youth in detention centers, pre-trial facilities, and prisons. Migrants now constitute nearly half of Berlin’s prison population, a threshold already crossed in Hamburg.

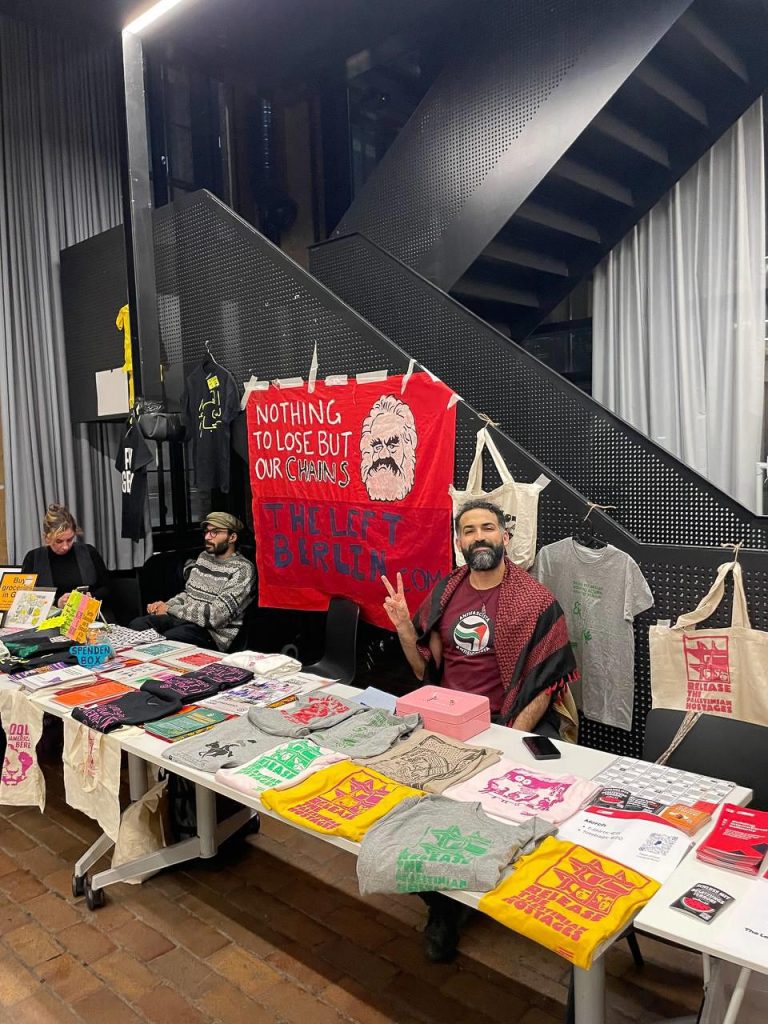

Behind these shocking statistics lie individual stories of young people who came to Europe with hopes and dreams and found nothing but a system that antagonised them. And this is no accidental policy; the criminalisation of these youth is a deliberate mechanism of racism and state violence. When we see these boys selling drugs in Kotti, we must see beyond the stereotypes to recognise the systematic forces that leave them with no legitimate alternatives. This includes the Dublin Regulation, which denies them asylum, the economic barriers that shut them out of formal employment, and the racist policing that targets them disproportionately. This crisis demands both awareness as well as solidarity. And hopefully through these stories, I can bring out the personal stories the statistics, reminding us all that each detention center bed, each prison cell, each street corner where a young person is forced to sell drugs represents the failure not only of society as whole but also of our activist circles that have not until now built structures to support these criminalised youth.

For more information, see White, green, or brown? written by the same author.