This article is the first piece in the series Neo-Nazis and Anti-Fascism in Germany since the 1990s. The rest of the series can be found here.

Kien Nghi Ha is a cultural studies and political scientist at the University of Tübingen whose work focuses on Asian-German Diaspora, postcolonial critique, racism and migration. He is also working as a curator and author of numerous books and articles. Most recently, he edited the volumes “Asiatische Deutsche Extended. Vietnamese Diaspora and Beyond” (Assoziation A, 2012/2021) and “Asiatische Präsenzen in der Kolonialmetropole Berlin” (Assoziation A, 2024). Right now, he is editing the volume „Anti-Asian Racism in Transatlantic Perspectives“ (transcript, 2026) and co-editing „Rassismus. Ein transdisziplinäres Kompendium“ (Springer VS, 2026) for the new book series „RACISM/SOCIETY. Transdisziplinäre Perspektiven“.

This interview was carried out in German and translated by the authors.

TLB: Let’s start with a hypothetical. You’re talking to an activist who has just arrived in Germany and knows little to nothing about what happened in Rostock-Lichtenhagen between August 22nd and 26th, 1992. Can you explain what took place?

Rostock-Lichtenhagen is a high-rise housing estate with high unemployment in the north of the city in East Germany, and known as a social hot spot. It was home to the central reception shelter for refugees. At the time, it mainly housed Roma refugees from Eastern Europe, and next to it was the Sonnenblumenhaus [sun flower house, an apartment block named for the sunflowers painted on the side], where former Vietnamese Vertragsarbeiter:innen [contract workers] lived. First, the central reception shelter was attacked by several hundred right-wing extremists in organized cadres from across Germany and abroad. They were supported by local activists and right-wing youths, with estimates ranging from 3,000 to 5,000 spectators who were celebrating these racist attacks. After two days, the central reception shelter was evacuated. Then, on the evening of August 24th, the Sonnenblumen house was lit on fire after the last police officers had withdrawn. The approximately 100 Vietnamese contract workers were able to escape to the neighboring house with a few German companions. They received very little help from their German neighbours. It’s a miracle that no one was killed in the Rostock-Lichtenhagen pogrom.

Rostock-Lichtenhagen is special because it is the largest pogrom since 1945, and was publicly celebrated in a festival-like atmosphere over several days. The police allowed this pogrom to take place, and it was broadcast live on television. This shook the very foundations of basic trust in German society and state. Namely that the German state, especially after the experiences of the Holocaust, has learned to protect fundamental human rights such as the basic right of physical safety for all people, not just for ethnic Germans. The trust in the German state and society, as well as the feeling of safety of Persons of Color was fundamentally shaken.

How did the media and politicians talk about migrants at the time, and how did that impact the pogrom?

Talking about the causes of this racist pogrom is a complex undertaking, but I will present the central points from my perspective. Preceding the pogrom in Rostock-Lichtenhagen was the so-called German reunification, which on the one hand greatly strengthened German nationalism, and on the other hand made many unrealistic promises that created high expectations. Chancellor Helmut Kohl said that German reunification would be accompanied by “flourishing landscapes in East Germany”. This promise failed miserably, because German reunification was accompanied by a severe economic and social crisis, with unemployment rising in both West and East Germany. In Rostock-Lichtenhagen [editors: which is in East Germany], figures from 1992 indicate 17% unemployment. The supposed national triumph had its shadow then, and the nationalists inside and outside of the parliaments began to search for so-called scapegoats.

They found refugees and migrants, who were both referred to as Ausländer [foreigner]. The concept of migrants, the concept of immigrants or people with a Migrationshintergrund [migration background] didn’t exist in the 1990s. We were just called foreigners, meaning anyone who wasn’t White or Western European. There are pages and pages of really terrible cover stories, headlines and quotes which the political and media discourse repeated on a daily basis, which are documented for anyone who is interested. Some of the harmful examples include terms such as so-called “Überfremdung” [literally: over foreignization], “asylum fraud,” “social parasites,” and “fake asylum seekers”. These were all extremely negative, dehumanising terms strongly tied to ethnic and national stereotypes, especially for refugees who came from the Middle East as well as Roma people who have had to deal with this racism for centuries.

This political campaign created an atmosphere in which the abolition of the constitutional right to political asylum was demanded throughout the country, and had a strong influence on the situation in Rostock-Lichtenhagen. The central reception shelter there was constructed for 300 people, but many more had arrived without capacity being expanded. As a result, the humanitarian situation deteriorated to an untenable level, and numerous reports said months in advance that this would lead to serious conflicts with the local population. These alarms were repeatedly ignored by local and state authorities.

Accordingly, when the situation then escalated in August 1992, the media and political discourse had already prepared the racist sentiment, defining who was to blame. We must therefore look to the politicians and the media as actors who created a political situation in which racist violence on this scale became not only possible, but expectable. Many of those who were involved as racist perpetrators in Rostock-Lichtenhagen also said that they felt legitimized by these mainstream discourses and the reactions of the ‘normal’ White majority population. They felt like they were carrying out acts that were strongly welcomed and demanded by the German population and its political elite. It is therefore false to claim that this racist violence was limited to extremist fringe groups who came to Rostock-Lichtenhagen from outside. This violence came from the middle of the White German society and was also welcomed by many who stood by as spectators, witnesses, and supporters of the pogrom.

TLB: Was there a response from an anti-racist or anti-fascist movement at that time, or some kind of solidarity?

Well, Rostock-Lichtenhagen was part of a chain of events. There was a series of fatal racist violence leading up to Rostock-Lichtenhagen starting well before the German unification process began. For example, there was Hamburg in 1980, where two Vietnamese Boat People Nguyễn Ngọc Châu und Đỗ Anh Lân were murdered by organized Neo-Nazis. Or Duisburg 1984, where seven members of the Satır family, who immigrated from Turkey, were murdered in a fire, probably by right-wing extremists, which has not been properly investigated. Right before Rostock-Lichtenhagen, there was the Hoyerswerda pogrom in September 1991. So when the pogrom started in Rostock, there were some local anti-fascist groups that tried to show solidarity and supported the residents of the Sonnenblumenhaus and the refugee centre in their resistance against these attacks. A small group of antifascist activists were even inside the Sunflower house during the days of the pogrom. Astonishingly, although the police claimed that they were very short-staffed and did not have enough officers on site [to prevent the pogrom], they still took the time to arrest these anti-fascist activists, limiting the resistance against the pogrom. On the first weekend after the attacks just a few days later, there was a nationwide demonstration with several thousand people under the slogan “Stop the pogroms.” Then, what was not possible at the time of the pogrom suddenly became very possible, the police mobilized 3,000 officers from across the country to keep left-wingers out of Rostock and repress the anti-racist protest.

TLB: Many incidents of racist violence that you mentioned happened in the East of newly unified Germany, although not all. How does this division between East and West Germany play a role in these racist incidents?

While I don’t want to downplay the difference of everyday racism between East and West Germany, the sole focus on it can distract from other even more significant questions. Perhaps we can replace this question, because I think there is a different aspect that is quite central, namely the all German debate on abolishing the constitutional right of mostly racialized refugees from East Europe and the Global South to seek political asylum. This debate aimed to restrict the fundamental right to asylum and to undermine it through newly invented legal constructions such as “safe third countries”.

The struggle for the right to asylum plays a central role in understanding the pogrom in Rostock-Lichtenhagen. It is not credible to claim that all the unbelievably gross mistakes on behalf of the state and municipal authorities were just incompetence, misunderstandings, or bad luck. But it is right to say that the pogrom was made possible by the fact that many high-ranking police officers left for vacation that weekend, even though the local newspaper had reported that right-wing extremist citizens’ initiatives were mobilizing and had announced a big bang. These and other circumstances were produced by choice and could have been completely different, if the representatives of these state institutions had taken obvious decisions. Even the mayor sent letters to the state Interior Minister stating that conditions were so bad that a murderous conflict could not be ruled out. UN reports on the sanitary conditions at the refugee centre deemed them as catastrophic. Nevertheless, nothing was done. These fundamental questions require explanation, as they contradict every conceivable normal administrative procedure: Why, with eyes wide open, did they allow the situation to escalate further in what was already a dangerous situation?

Looking at the whole situation in the political context, there were strong efforts, especially from the mainstream conservative parties (CDU and CSU), to restrict the right to asylum since the end of the 1970s. It was a central election campaign issue in the 1990s, seeking again to explain the miserable national unification to the disappointed voters in a bid to secure power. For example, in September 1991, the CDU launched a nationwide campaign in which all local party branches were asked to report asylum emergencies in order to give this issue frontpage media coverage. Then, in October 1992, just two months after the pogrom in Rostock-Lichtenhagen, Chancellor Helmut Kohl pointed to a state of emergency due to the unwelcomed arrival of refugees. For a long time, the oppositional SPD had resisted stripping the right to asylum, invoking the lessons of German’s Nazi history to protect the politically persecuted. But it is clear that the popularity of the pogrom in Rostock-Lichtenhagen within large segments of the German voters and the political pressure in the media coverage also caused the SPD’s political resistance [against the CDU’s project] to collapse.The SPD agreed in December 1992 to participate in this project in order to achieve the two-thirds majority necessary for constitutional changes.

So you see, both before and during the pogrom in Rostock-Lichtenhagen, this racist violence was instrumentalized to turn the problem around. In this discourse, racist violence was seen as the answer to the problem caused by a liberal asylum law. Not only was there a reversal of perpetrator and victim, but also a reversal of cause and effect. About two weeks after the deadly arson attack on the Aslan family in Mölln by rightwing activists, on December 6th 1992, a decision was made to conclude a so-called asylum compromise between the CDU and the SPD. There are theories that the anti-migrant and anti-refugee discourse, which provoked widespread racist violence, was meant to be a kind of calculated escalation to soften up the SPD so they would give up their opposition and finally agree to restrict the fundamental right to asylum.

This is one of the long-term effects of the Rostock-Lichtenhagen pogrom, the amendment of article 16 in German Basic Law. This means that the fundamental right to asylum for politically persecuted people is permanently restricted in Germany. Accordingly, this raises the question of whether it was a pogrom. A pogrom is characterized by a socially dominant group taking action against a racialized minority, while being supported or at least tolerated by the political institutions in the country. We can recognize all three of these elements in the Rostock-Lichtenhagen case.

This makes it insightful to look at why it took 30 years for the term “pogrom” to be used in official statements in this case. On the 30th anniversary, the city of Rostock referred to these events as a pogrom for the first time in a press release. Just one month before that, a study by the scientific service of the Bundestag had already cited Rostock-Lichtenhagen as an example of a pogrom. Interestingly, the term that is most accurate to understand this event, was avoided and marginalized in mainstream political and media discourses, who preferred terms like clashes, conflicts, riots or even protests. But the term “pogrom” eventually became more established and mainstream after a long struggle. I think the reasons for this have a lot to do with the exposure of the National Socialists Underground (NSU) terror scandal in 2011, and the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020. These made the issue of institutional racism a topic of discussion in the media, and people began to conceive of racism as an institutional problem. Accordingly, it became possible to view the pogrom in Rostock-Lichtenhagen as a problem of institutional racism.

TLB: In your work, you write about the pogrom as institutional racism, describing some aspects that you’ve already mentioned now in the context of the pogrom. Could you expand on that?

For me, it is particularly important to analyze Rostock-Lichtenhagen, not only to consider its background and the course of events as part of this institutional racism, but also to examine what happened after the pogrom. Namely, whether there is a process of coming to terms with the past or not. How do we deal with it in terms of memory politics, political justice and material as well as legal compensation? Who bears responsibility? And to be more specific: How did the police deal with their responsibility in retrospect? How did political institutions such as the state parliament of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern or the city of Rostock deal with their responsibility? How did the judiciary deal with it? How did academia deal with it? What kind of cultural processing took place and what kinds of memory political discourses or public events were established?

When you work through all these questions, you can see that there are huge gaps. It would go too far to explain these different areas in detail here, but I have done that in my analysis. In this case, we can see that the institutions that bear responsibilities are not fulfilling their working duties. One way of defining institutional racism or institutional discrimination is to say that if marginalized groups do not have access to the services they can expect from the institutions, such as adequate legal and political processing, then these institutions have simply failed and have discriminated against certain groups. And this failure is a structural pattern that we see again and again when it comes to dealing with racist attacks and discrimination. We see this not only in the case of Rostock-Lichtenhagen, but also the NSU or the racist murders in Hanau and other cases.

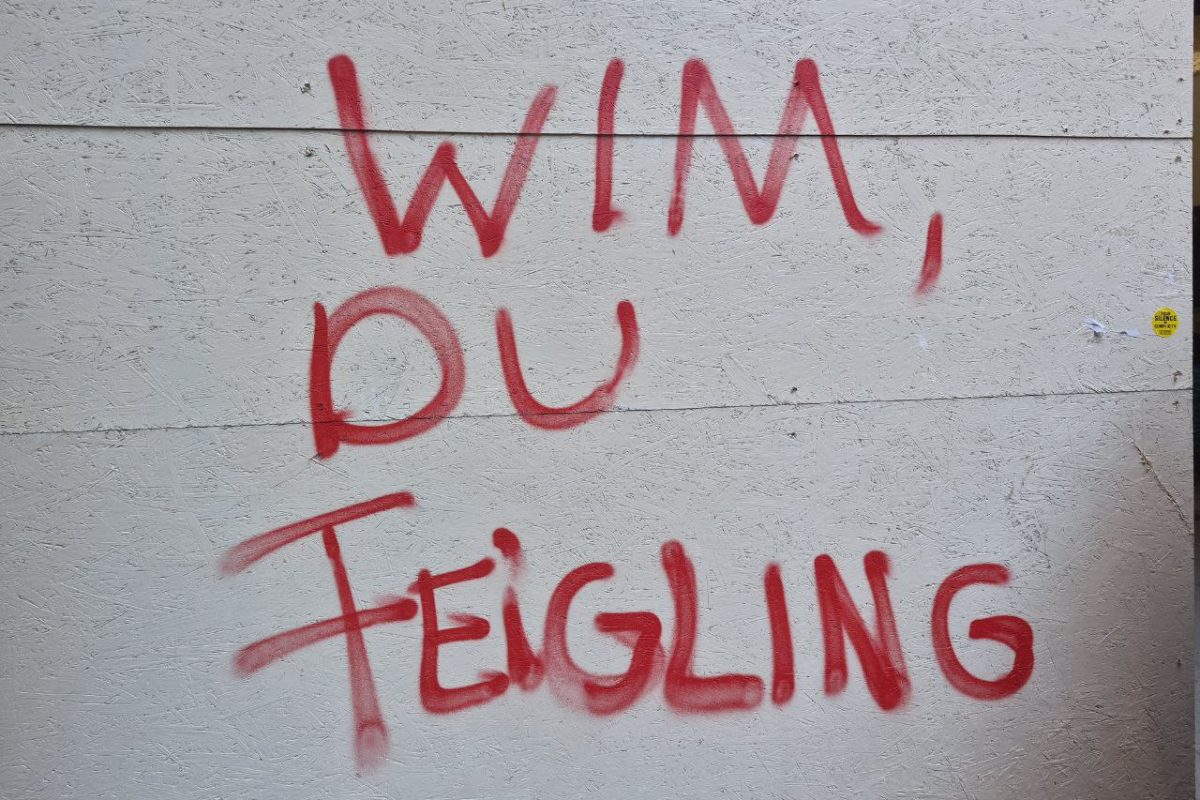

And that’s why it is important for me to put the image of Rostock-Lichtenhagen in a different context. Because Rostock-Lichtenhagen is defined by these very emotional and also terrible images of a violent mob cheering and throwing stones or molotov cocktails, and you think that’s just crazy Nazis celebrating a German folk festival. What you don’t see, however, are the institutions that made such images and events possible in the first place through what they did or decided not to do. Because otherwise, we slip into a convenient discourse that sees racism as a marginal problem of a marginal German underclass that has been left behind. Part of the discourse around Rostock-Lichtenhagen was this talk about the ‘losers of the German unification,’ who are uneducated and impoverished and who, as a result, cannot represent normal German society. That is how Rostock-Lichtenhagen is separated from the German normality. Also you don’t see that this pogrom was made possible by political elites, so-called think tanks and highly regarded media professionals. They also have a big responsibility we should not forget to examine.

TLB: There is now more scholarship and writing about this topic. But how was the memory of Rostock-Lichtenhagen fought for, and what exists of this memory today?

There have been major changes in recent years, mainly due to criticism of how the mainly White anti-racist movement organized the nationwide memorial demonstration on the 20th anniversary. I was not only the sole Vietnamese, but also the only speaker of Color in the 2012 commemoration. In comparison, the nationwide demonstration on the 30th anniversary in 2022 had much stronger participation from Asian-German communities and engaged a broad Coalition of Color. The commemorative rallies have become more pluralistic, with those affected more involved than in 2012. The 30th anniversary was also more present on social media, making it easier to access the topic for our communities outside of Rostock.

In Rostock recently, there has also been more space and freedom for civil society to address structural racism. Further, the criticism of the public commemorations in Rostock led to the city finally establishing a decentralized institutional commemoration for the first time in 2017, on the 25th anniversary, by erecting memorials at various locations throughout the city, something which has been demanded for a very, very long time.

I believe that there has been a certain opening up of this discourse of memory politics, although with a lot of shortcomings. To use an example, the city of Rostock, the jury, and the artist group who created this memorial in 2017 did not think of the basic need that the memorial should also acknowledge the victims of the pogrom. Therefore, an addition to the memorial was created one year later. Today, even this limited opening is currently in great danger, because we live in a political situation where not only the AfD and other right-wing forces are gaining ground, but the federal government is quite obviously targeting critical civil society organizations. And accordingly, the space for political maneuvering, including the space for a memory politics that is structurally critical of racism, could be reversed.

TLB: When you look back on the role of political and media discourse at the time of the pogrom and then you look at today’s political discourse and the media, what do you recognize, or what has changed?

Well, there is a major backlash that we are currently experiencing. This includes both Trump and his team in the White House, but also power relations in Germany itself. We are experiencing a culture war in both countries. The question of whether we are allowed to state what we see is not limited to Gaza and the wars in the Middle East. Likewise, after the media fueled anti-Asian stereotypes at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, there is reason to worry that anti-Asian and especially anti-Chinese stereotypes will rise massively in the coming years in the wake of geopolitical conflict and economic competition with China. I also think it is foreseeable that the colonial racism that seems to have been addressed in recent years through decolonization debates will be revitalized in a new form. I don’t expect that a large part of the Western media will resist this trend. In the mainstream media, self-criticism is usually only practiced or exercised after the damage has long been done and mild criticism is then risk-free or convenient.

Accordingly, I actually see a lot of similarities with the political, cultural, and media conditions we experienced in the 1990s, when there was also a huge revival of nationalism and racism. In Germany today, very similar phenomena are obviously present. So it is very important to address the question of what the 90s could mean for the present, although that’s a rather sad conclusion. Ultimately the political events are very strongly dependent on the social balance of power, and if there is a resurgence of nationalistic, racist, and also militaristic logic in this social structure, then this will naturally also break out in the media and in politics. But affected people and smart progressives are not and will never be defenseless. There is always a solution right behind the corner!

TLB: Thank you. Is there anything else we haven’t covered that you would like to share with our readers?

I think if we understand Neo-Nazi violence as an extension or escalation of normal social conditions and not as its contradiction, it is interesting to discuss how this racist violence is embedded in colonial capitalist production and hierarchical relationships as a state of social normality. That would enable a new approach to the whole issue, which would be a completely different conversation. Nevertheless, I find it interesting to ask about precisely these connections and not to view racism as a topic that is disconnected from other socio-economic relationships and cultural contexts, but rather as something that is evidently very strongly linked to capitalist processes of exploitation and valorization. I think that colonial stereotypes can only be understood in this historical context, and if we want to understand racism, we have to look at it in this way. Then it becomes very clear that colonialism and capitalism have developed together and that these structures are very strongly correlated and overlap with each other. Accordingly, I think we definitely need to open up the analysis of racism in this direction and seek exchange there.

TLB: Thank you very much for taking the time to speak to us.