In 2010, the so-called “Spycops Scandal” broke, eventually revealing that UK undercover cops were used to infiltrate social movements in the UK and internationally. At least a dozen of these cops apparently had intimate relations with activists who did not know their real identity. Some had children. Berlin-based activist Jason Kirkpatrick discovered that at least one of those cops, Mark Kennedy, had been deployed in Germany to target him, and infiltrate the movement planning protests against the 2007 G8 summit in Heiligendamm, Germany. We spoke to Jason, whose film about the scandalous Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) spycops unit will be soon shown in Berlin.

Hi, Jason, thanks for talking to us. Could you first start by introducing yourself? Who are you? What do you do?

I’m Jason Kirkpatrick. Currently, I work at a Ukrainian-based peace and clean energy group called Razom We Stand. I’ve been an activist dealing with environmental, climate, human rights, and peace issues since the end of the 80s.

You’ve produced a film, which is going to be shown in Berlin soon. How did you get into film production?

It started with the outing of spy Mark Stone, who was, I thought, a very good friend. It turned out that he was a British spy whose real name was Mark Kennedy. At the end of 2010 he was uncovered by his activist girlfriend, who didn’t know his real identity until she saw it on a passport when they were traveling on a road trip through Europe.

I found out from a friend here in Berlin. I was completely shocked to find out this guy who I thought was my friend was a spy. We found out that he was working under a contract with the German police (LKA).

Within a couple of months, following the “spycops scandal,” Mark was all over the UK news. At first the British police said: “Mark Kennedy is just one bad apple. He’d admittedly slept with a couple of activists. but that’s just a one-off case”. It turned out that Kennedy was one bad apple amongst a whole barrel of abusive cops, in a political policing unit that dates back 1968, and had even targeted the famous German 68s radical Rudi Dutschke

To summarize the spycops scandal, British policemen developed relationships and had children with women who didn’t know they were cops.

Yes. Cops regularly and routinely had intimate relations, and even planned children with activists. More than one of these activist women have told the media that they felt raped by the state. I’ve heard that again, including yesterday in a telephone call with one of these women. If someone deceives you, that’s bad enough. But when it’s a 5 year relationship, or you have planned children with someone paid and trained by the state, who suddenly disappears and leaves you to raise that child alone, that’s traumatic.

The story broke in 2010, and it just got bigger. The police in Britain have made massive apologies and massive payouts—over £400,000 in one case. In 2015, the former Prime Minister Theresa May called for an Inquiry, which is still ongoing.

And the year after these revelations, you found that your “friend” Mark was one of these spycops. How did you react?

I immediately talked to members of the British press and said that Kennedy was also in Germany. I was interviewed by the British Guardian newspaper and German newspapers like the Taz in 2011. I also went to some contacts I had in the German parliament in the Green Party and the Left Party. They started asking parliamentary questions; “Why was a British spycop in Germany, spying here? Why? Who paid him”

It came out that the German police (LKA MV) actually had a contract with the British police to have Kennedy come here and spy on activists, especially around the G8 summit protests in 2007 in Heiligendamm near Rostock.

How many police were involved in this?

We know that there have been 200-or-so spycops in Britain in a formerly secret division called the Special Demonstration Squad, or SDS. They started in 1968 after a big protest in London against the Vietnam war that went to the US Embassy. It turns out that the police leader at the time told the Home Office: If you give me a million pounds, we’ll make sure these protests never happen again. We’ll infiltrate them.

And that’s what they did. They infiltrated protest groups, peace groups, women’s groups, all sorts of advocacy groups, animal rights groups, from then until today. And this is still going on now.

You say it’s still going on. You might naïvely think that after the Spycops Scandal, this would be stopped.

One could naively think that police were embarrassed by this scandal of police abuse, but political policing continues, as recently exposed in Bremen. We know why—because people in power are insecure and afraid, and use every tool of the state they can to protect their power.

In the UK, we found out that they’ve used undercover police against direct action and climate groups like Extinction Rebellion. In the USA, a wave of FBI repression against groups like Earth First was exposed in the 1990s. In Germany, for years peace, human rights or environmental activists have been wrongly labelled as extremists, and this loose term is used by security services to target activists.

How does this link to the recent case of police in Bremen infiltrating the Interventionistische Linke?

This is really interesting for me, because the Interventionistische Linke was one of the groups that I organized around. I wasn’t a member, but they organized with me and many thousands of others against the G8 in 2007. Now we see that the police have infiltrated them in Bremen. These activists must have been doing something right.

The police are targeting anybody who wants social justice and an end to these kinds of abuses.

How were you personally affected?

I was doing press work for a group called the Dissent network. We were organizing protests and activist camps in the areas around Heiligendamm. I was in a Infotour group giving public lectures, sending press releases, training activists in media skills and organizing interviews with journalists. I’ve since gotten some of my police files in Germany and England, and found out that I was targeted because I was dealing with the press and I was seen as a spokesperson. These police, and the big firms that profit off the fossil fuels causing climate chaos, for example, don’t like the pressure we were putting on them.

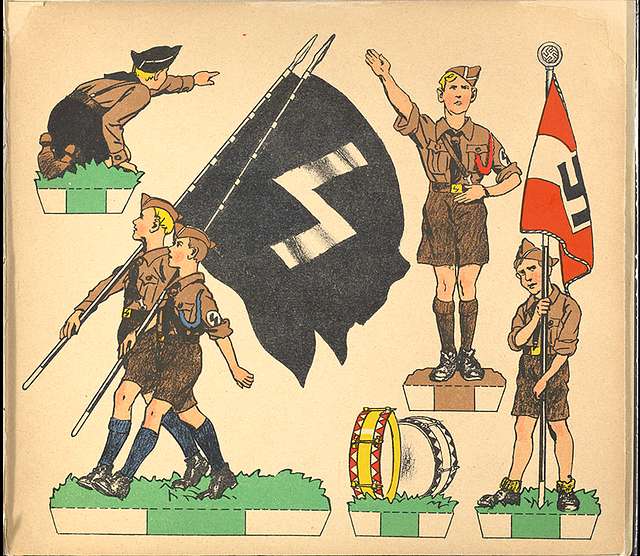

Doing journalistic work is supposed to be protected by the constitution. Everyone’s supposed to have freedom of speech. But that definitely was not the case when Kennedy was targeting me. In the end we see again and again that Kennedy and these Spycops were on the wrong side of history, and they were effectively doing pro-racist, pro-fascist, anti-equality, and anti-climate work by repressing justice movements working for a better world. Kennedy’s specific tasking appears to have had the effect of sabotaging the climate movement, so he effectively was an expensive publicy funded tool of the corporations causing the climate catastrophes.

Why did you make this film?

When this scandal first broke in 2010-2011, we got a bit of press. The police were saying that Kennedy was just one bad apple, and the police never do such bad things. Many of us saw that this clearly wasn’t the case; clearly, Kennedy was part of a larger system. The parliamentary questions in Germany exposed that Kennedy had a contract with German police, and that spycops regularly cross borders.

I thought that this was a big enough scandal to warrant a film. In 2011, I started shooting a documentary, telling my story in Germany and the stories of some of these women. I interviewed a whistleblower named Peter Francis, who’s been in the media quite a bit in England. He’s a former undercover cop, who exposed the scandalous racist work of UK undercover cops.

However, by the year 2018 I wasn’t able to finish my film as thoroughly as I wanted. I met another British filmmaker who said: I’m starting to make a film in England, and I want some of your footage. So I gave him my material interviewing a couple of these women, the whistleblower Francis, and a couple of others.

The Director ended up using a good amount of my footage in his film, which is called The Spies Who Ruined our Lives. I took on the role of co-producer. I get asked more and more to show it in cinemas and different activist centers, and the reception has always been very good. People have been fascinated and shocked to see the film and hear about this scandal.

Who is the film for? Is it for activists or for “normal people”?

I would say it’s for both. It fits very well for activists who know a bit of the background context. They can jump into the themes a bit easier because it gets complicated, especially with this British undercover policing inquiry, which has now spent over £100 million. It’s currently the longest ever British inquiry, at 11 years – longer than the Northern Irish related Bloody Sunday Inquiry, which took 10 years.

It’s such a scandal seeing these women tell their stories and hearing from former British ministers who campaigned against apartheid and were targeted. It’s almost so complicated that you have to see a film about it to understand it.

After showing the film on Saturday 21st February you’ll be doing a Q&A accompanied by Kate Wilson. Who is Kate, and what has she got to do with the film?

Around 2005, Kate was living in Berlin. We became friends. Mark Kennedy visited us both in Berlin, and we had a lot of good social times together. Kate had a relationship with Mark for around two years, and after the scandal broke, she took legal action, which she won a couple of years ago. The British state tried to stop her at every point.

She’s going to be here this weekend telling her story, because she’s also written an amazing book called Disclosure: Unravelling the Spycops Files. It tells of a 15 year struggle against the British state for justice. A big part of it is just struggling to get the facts and the truth of the story about what happened to her. Who gave the orders? Why did Mark Kennedy spy on her for so long, entering her family life? It’s an amazing book, and she has amazing stories to tell.

What are you trying to get out of these court cases?

A lot of us want to know who gave the orders. How does this spying work? Why were we targeted? Were we targeted individually or as groups? We want to know the background.

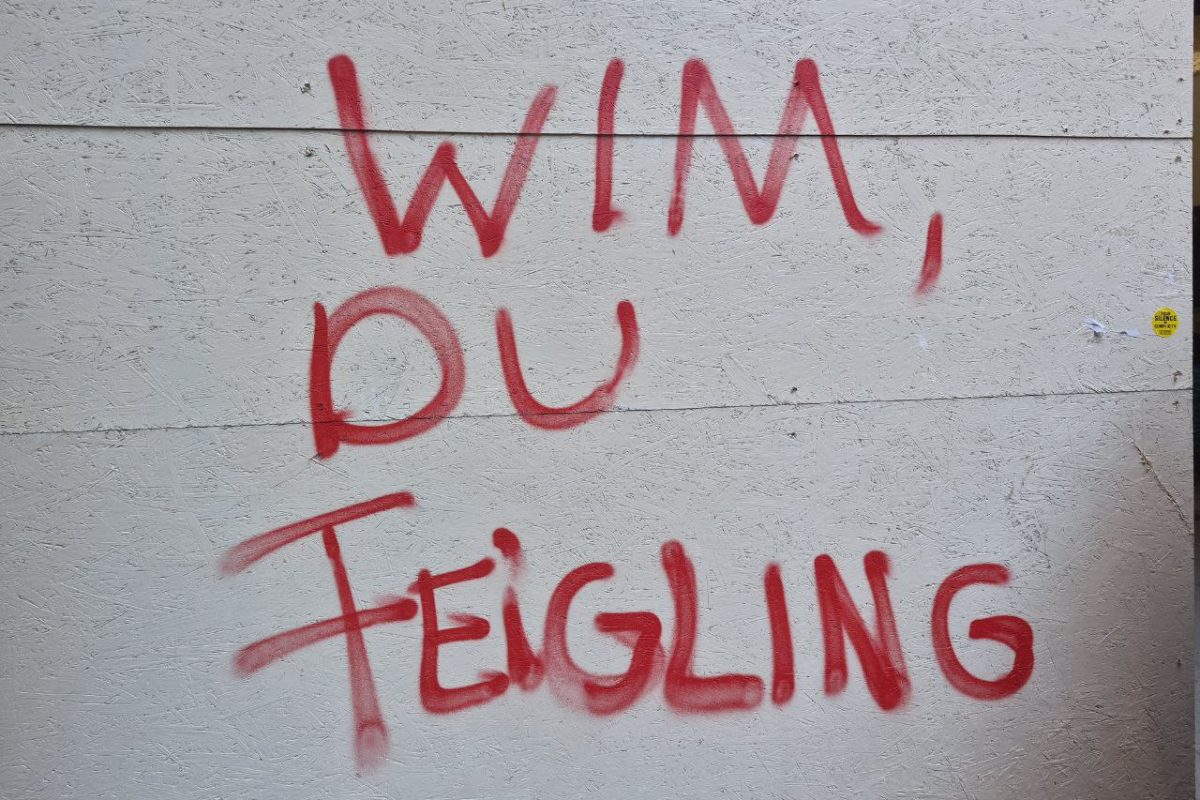

Mark Kennedy hasn’t earned himself the best reputation among especially the women friends of mine. He’s had every chance in the last 15 years to come out and help the victims of his abuse. He could have been a whistleblower. He could have told the truth. He could have said: “this is why I did what I did, and here’s who gave the orders.” He hasn’t done that yet.

Why do you think that the police behave this way?

When they see activists and activist movements growing, police and politicians can feel their power being threatened. This happened with the anti-racist movement in the 80s or 90s in Britain, and the movement against fossil energy now. As the climate movement grows, they want to know who’s possibly going to be taking power from them. And they use every tool they can to stop us, but we aren’t intimidated.

What should people do after they’ve seen the film? Do you want to encourage people into doing something specific or is it just about informing people?

It’s always good to be informed, but also to turn information into action. Once you have more information, you know a little bit more about where you can best use your energy to make change. The message that I’d like to carry forward is that all the activism we were involved in was creating change, and that’s why it flagged up these security services. What we were doing was right, and we often won despite their efforts to stop us.

These spycops fall on the wrong side of history again and again. But we are on the right side. The anti-apartheid movement was targeted by these police. Luckily, apartheid lost. The climate movement has been targeted by these police since the early stages. In Germany, I shouldn’t have to explain why that’s a problem. But again and again they have targeted anti-fascists. Mark Kennedy asked me if I knew a Fascist that we could attack together. I’m supposing he wanted to provoke and try to get someone arrested. Kennedy, in effect, was doing pro-fascist work in Germany. What a disgrace.

You said earlier you’re more an activist than a film maker. What’s the specific role of activist film makers?

The thing that is really, really difficult with film making is raising money. I wanted to make a film that wasn’t just going to be shown to a few people here and there. But you have to get copyrighted images, a soundtrack, all this post-production work. You’re talking about at least €100,000 euros for a film that’s going to be shown in cinemas and distributed. It’s just not going to be good enough quality for less than that.

Having said that, storytelling anywhere is important, whether it’s on social media, on Instagram or whatever. That human part of activism needs to be used to change minds, because people connect to other people’s stories. We can put out facts and figures and statistics proving we’re right, but a lot of evidence shows that facts are not what actually changes average people’s minds. But human stories, and connecting to real people is.

What’s next for you? Will you be making a new film or just carrying on with your activism?

I’m carrying on with my activism as Head of Communications at a Ukrainian non-profit right now; Razom We Stand. I’m very happy in that job, and I think it’s a great project with people I knew a little bit before from circles of climate and clean energy activism.

We see now clearly that the war in Ukraine is fuelled and shaped by Russia’s export of fossil fuels. If Germany, Europe and the rest of the world would pivot to clean energy, which is cheaper, then Russia wouldn’t be able to finance the war, and we would have peace in Ukraine.

The film The Spies Who Ruined our Lives (English with German subtitles) will be shown at Lauseria, Lausitzer Straße 10 on Saturday 21st February at 7pm, followed by a Q&A with Jason Kirkpatrick and Kate Wilson. On Friday 20th February at 7pm, Kate will be presenting her new book Disclosure: Unravelling the SpyCops Files in Aquarium, Skalitzer Straße 6,