At the end of 2025, three articles once again articulated—from different perspectives—the silence and failure of political discourse in the art scene. David Velasco, long-time editor-in-chief of Artforum, the US “North Star” of art criticism, reflected on and recapitulated the past two years of “division, fear, and silence” in Equator, the British online magazine for politics, culture, and art. In October 2023, a few weeks after the Hamas attack in Israel and the publication of a letter of solidarity on the Artforum website signed by more than 8,000 people calling for Palestinian liberation and a ceasefire, Velasco was fired without notice. Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, who had been director of Berlin’s Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW) for just ten months at the time, summed up shortly before Christmas that he did not want to get drawn into political debates, but rather “talk about humanity in the coming years and decades, perhaps for the rest of my life […] so back to those Christian values we always talk about.” A few weeks earlier, Berlin-based artist and activist Adam Broomberg had published a scathing critique of the “Global Fascism” exhibition at the HKW.

At the end of his essay, Velasco writes that he has spent the last two years in an “unofficial hiatus” from the official art world. His final sentences: “It’s increasingly hard to care about the fate of an art world narcotised by money and self-regard. We had a chance to at least try and make a difference. We had a chance to not sell ourselves out. We had a chance, and we blew it. This did not end well, and still we can choose to begin again, tilting—collectively, contingently—toward the pitch of liberation.” He does not elaborate on his optimism. I would like to share it, because capitulating to the power of the market and the violence of power has also mentally catapulted me out of a “scene” that I always wanted to understand as a left-liberal seeking a self-critical public sphere. This basic trust in a shared world, which uses artistic work to address the dilemma of subjectification and subjugation, of deviation and form, has been shattered. Definitively after October 7, 2023. In recent decades, during which I was involved in the art world as a writer, researcher, and curator, there have been various phases in which momentous political events—such as the imposition of martial law in Poland in 1981, the first Iraq War in 1990, the Tiananmen Square massacre and the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, and the crushing of the so-called Arab Spring after 2011—during which I was unable to find the peace of mind to turn my attention to individual works. But art also participated in all these events, albeit with a delay. Without the work of artists, the discussion about the colonial basis of power in the Western world would probably have remained confined to academic circles in Europe for a long time. In this very world, there is now—once again—talk of the “end of the West,” of democracy, of the transatlantic alliance. In 2003, an important congress was held at the HKW: “Former West” (March 18-24). From the flyer: “Although the events of 1989 shook the world to its foundations, the West stubbornly clung to the fiction of its own superiority. Former West examines how contemporary art can unhinge this fiction and at the same time rethink the future.” The fiction is gone. Which art points to the future?

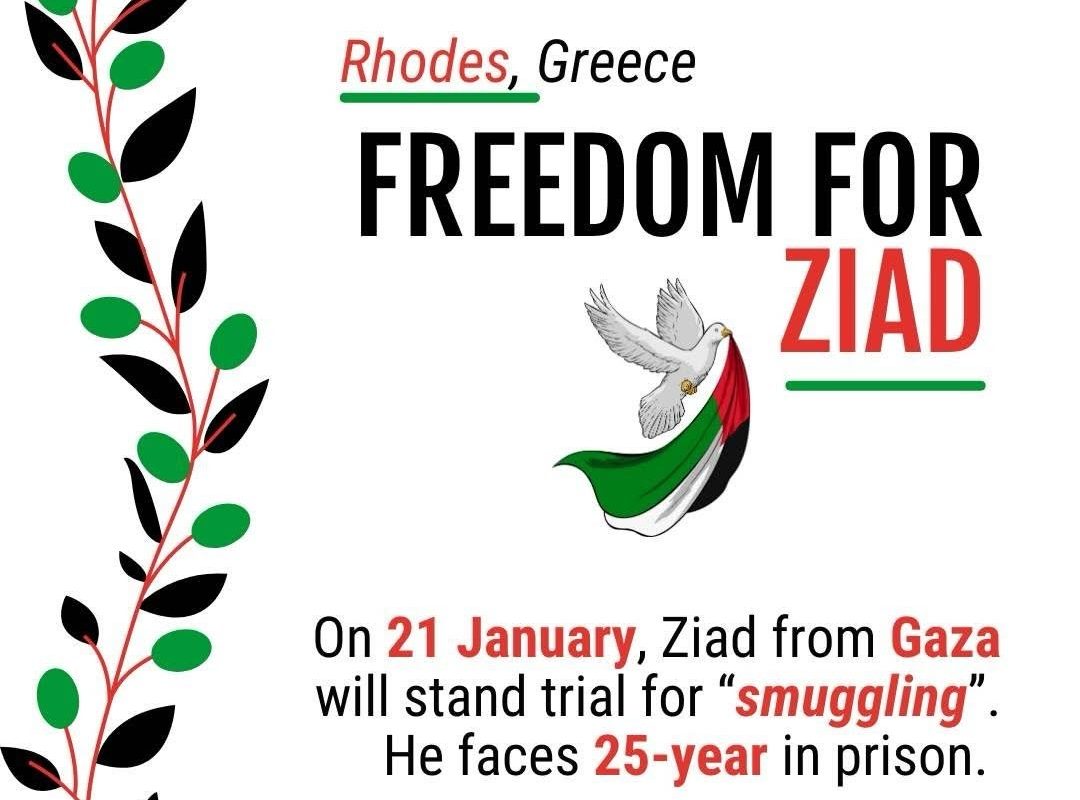

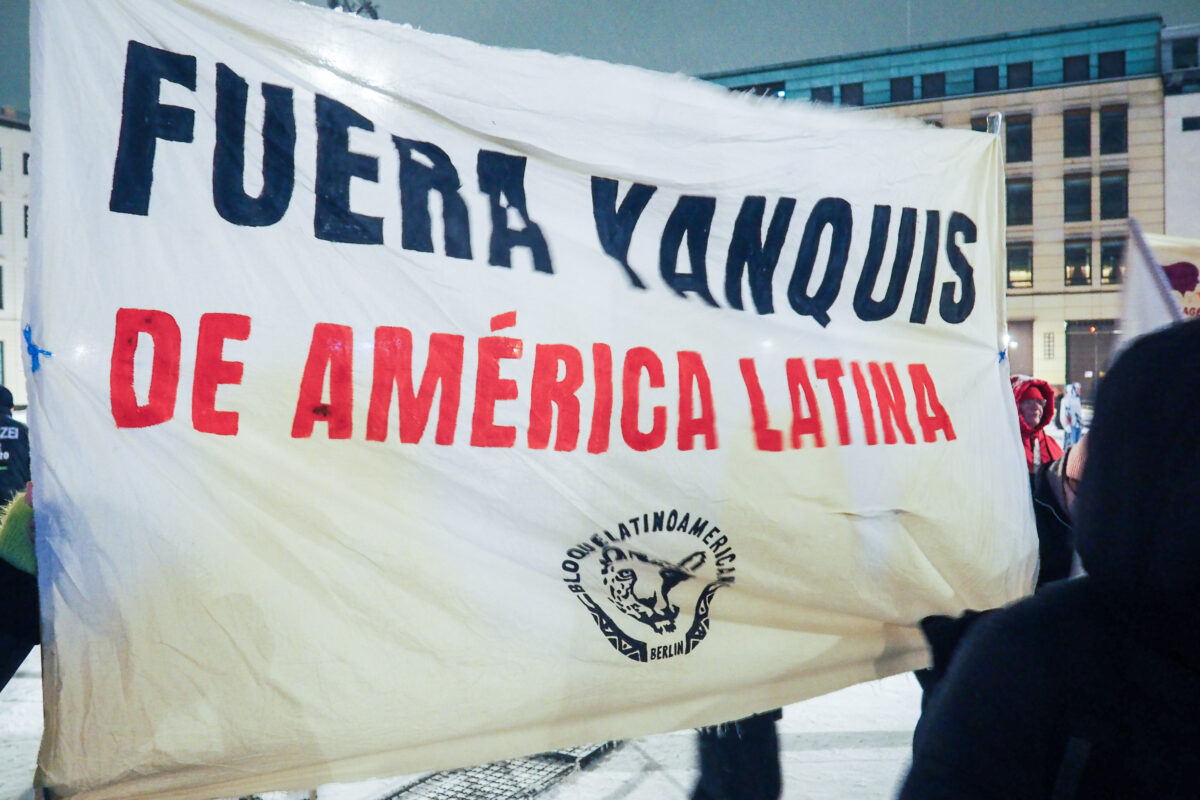

In his text, Velasco reconstructs how—not so much why—Gaza broke the art world. The means and methods were repressive: staff dismissals, cancellations of exhibitions and award ceremonies, criminalization, and legal prosecutions. In the context of art, it was (almost) always just about language and images—not about violence, sabotage, or self-interest. It was about words and works demanding justice for Palestinians (including the right to mourn) and an end to Israel’s internationally supported armed violence, which killed tens of thousands of Palestinians in a very short time. In the “cultural nation” of Germany, “reasons of state” became a tool to intimidate and silence criticism of Israeli policy (see archiveofsilence.org). According to Velasco, grandiosity “is one of the art world’s key features, the soil for its spectacular financialisation—its unparalleled ability to transform radicalism into capital. This grandiosity was inflected in much of the bright and lofty material that we published. The stakes were high; we believed we were writing history, and we often were.” During the crackdown on the Gaza protests, it was the collectors, galleries, and institutions that demanded ‘calm,’ not the artists. “Some collectors are calling up individual artists who signed, threatening to sell off their works or stonewall exhibitions by refusing to lend to museums. […] I am aware that much of the sentiment is divided by class: the letters’ signatories are mostly artists, the letters’ detractors are mostly their dealers and collectors. This is not a new rift in the art world, but Palestine seems to have deepened it beyond repair.”

What was striking in Germany after the Hamas massacre and the subsequent sanctioning of Palestinian solidarity was the role of curators and directors of art institutions, who positioned themselves hierarchically and firmly above the “opinion” of artists. Velasco highlights a prime example of this: Klaus Biesenbach’s distancing speech at the opening of Nan Goldin’s exhibition at the Neue Nationalgalerie. In the spring of 2024, however, two artists, Bank Cenetoglu and Pirvi Takala, confidently canceled their exhibitions at the Neuer Berliner Kunstverein because, in their opinion, its director did not distance himself clearly enough from Israel’s war policy. No artists, no exhibitions. Marius Babias then published a cryptic statement: “We are seeing increasing attempts to instrumentalize conflicts for personal agendas and reject the adoption of predetermined political positions.” It becomes apparent in that and his interview with the Berliner Zeitung, that his understanding of art is as the pure language of the works versus a political language and which politics lies behind this idea. “For us, the artwork is in the foreground; the messages should be codified in it.” (Spiegel) It is about the detachment of the work from everything: from the author, from an external artistic public, in principle also from its time, in order to propagate concepts such as autonomy, independence, and institutional self-determination—but only within the framework of the White Cube. This is the place where art is negotiated and nothing else. The institution exists precisely to maintain this fiction. To the point of self-appeasement, when Babias says: “In practice, the Bundestag’s resolution on the BDS is irrelevant to us. That was and is symbolic politics. […] We deliberately did not sign GG 5.3.1, like many other institutions. As it now turns out, the initiative further politicized the debate and polarized the arts instead of defusing it. […] The anti-discrimination clause in its originally proposed form would have had just as little impact on us as an institution as the BDS resolution.” One can only hope that such wishful thinking will not be followed by a rude awakening… Babias’ concept of art refers to the Enlightenment and fascism, mentions postcolonial discussions, but does not mention that all of this could also have an impact on the concept of art, the art system—if it were not immediately absorbed by the cunning of capital (see Velasco). Curators are a new profession that cultivates and encloses art. Previously, only art historians held leading positions.

The Berlin art bubble is international. Many artists who live here have fled repressive and violent regimes. Many also refer to the knowledge and experiences of non-Western and indigenous practices in their art. Why is criticism of “our art system” not becoming louder and more radical? I often recall a conversation I had with London-based Roma artist and curator Daniel Baker in 2020 on the occasion of the FUTUROMA exhibition in the Venice Biennale program. The exhibition attempted to transfer the impulse of Afrofuturism—namely, to retell history from a subject position—to the discriminated community of GRT (Gypsy Roma and Traveller). Among other things, he said: “The idea of a closer connection between the practices of art and life also has implications for reclaiming art from the privileged arena of the museum and an art world focused on market interests and knowledge hierarchies—on a separation of intellectual, cultural, and financial capital.

“You live in Florence, the birthplace of autonomous art, and encounter the meaning, power, and joys conveyed by Renaissance artworks on a daily basis. At their core, however, these objects remain instruments of the power of the state and the church. The audience is convinced of the transcendental nature of art, of its beauty and skill, which serve to promote ideas and narratives that point away from everyday life and toward the deeply spiritual and intellectual. This model of separation is how the modern museum is still understood, and from my perspective, there seems to be little appetite for approaching things differently.”

Returning to Ndikung’s interview with Deutschlankfunk, he suggests that he can work freely as a curator without taking a position in political debates: “My only position is humanity. I will not compromise. […] I don’t care who is holding the gun. That’s why I won’t get drawn into this debate. And my job is to keep the spaces open, to keep the art spaces open. People from Palestine, from Israel, from Syria, from Haiti, from Myanmar, and elsewhere will always have a place in [the HKW] to present their artwork.” That sounds confident, as if it were possible to stay away from power constellations, even to free oneself from them, even when working within them.

In his aforementioned text about the “Global Fascism” exhibition at the HKW, Broomberg mentions the necessary, subtle “anticipatory obedience” of a state institution in its concrete exhibition policy, and reminds us that its director also had to clearly distance himself from BDS before taking office. In 2014, Ndikung allegedly wrote on Facebook: “You will pay millions for every drop of blood in GAZA! Palestine must be free […] come rain or shine!” and signed the open letter from the “Initiative GG 5.3 Weltoffenheit” (Initiative GG 5.3 Cosmopolitanism), followed in 2021 by the open letter “Palestine Speaks,” which called on the German government, among others, to withdraw its support for Israel. Yet in the 2025 interview, Ndikung speaks for “humanity.” Meanwhile, Broomberg criticizes how “Not one work in the [Global Fascism] exhibition acknowledges the world burning just beyond the door.” The only Palestinian artist in the exhibition is represented with a work from 1974, which is described in the exhibition guide as “a possible allegory about the burden of Palestinian existence under occupation.” Broomberg’s bitter conclusion: “What were once our most progressive institutions and artists have become instruments of that silence, helping the genocide to proceed politely. When an institution reaches this level of corruption, it neutralizes any political potential of the art it shelters. Every work becomes a prop in the pretense of inclusion, queerness, Indigeneity, and postcolonialism. This theater serves the institution’s simulation of anti-fascism. […] The fact that these institutions—apparently in full seriousness—engage with ‘global fascisms’ while blithely enabling it at home is salt in the wound of the German cultural scene’s demise.”

In public institutions, one can assume a direct relationship of dependency between management and the state, i.e., obedience. In so-called “grassroots democratic” institutions such as the numerous German art associations, power is exercised through the rules of representative democracy: the members elect a board of directors. And this board is usually not made up of artists and citizens, but of potential sponsors (savings bank directors, private patrons, collectors). On the surface, it is often said that they alone are in a position to personally absorb the financial risk of failure—although this has long since become an industry for insurance companies. I never wanted to work in “powerful” institutions, perhaps because I took the pressure to represent too seriously. But in both art associations where I worked as director, I learned how fragile the protection of artistic freedom is. When I wanted to exhibit Hans Peter Feldmann’s cycle “Die Toten” (The Dead) at the Badischer Kunstverein 25 years ago (the independent book publication was already available), the board blocked the exhibition preparations and invitations could not be sent out. The work “Die Toten” documents, used previously published media images: 100 people who died between 1967 and 1993 in connection with the RAF—victims of the RAF as well as RAF members. After extensive discussions, in which Feldmann also participated with written statements, the conflict finally culminated in a meeting at City Hall and the question: Is the art association free in its work or should it be closed down? The conflict did not escalate further, the exhibition took place, and the art association was able to continue its work. However, if the representation of artists in art associations becomes too strong structurally—precisely as association members—this is often stopped, off the record, of course, as happened in the second association I headed. A tacit agreement then prevails between the financial backers (in this case, the state) and the board: it is better to remain among ourselves and retain control. There would be much to discuss…

Who decides what is permitted and in whose name? Is the political sphere limited to “state and civil society representatives, parliaments, global courts, organizations such as the United Nations or the UN Security Council,” as Babias told the Berliner Zeitung? It is not the controversy over “autonomous” art and activism that is decisive, but the recognition of power over (artistic) publics.

Now, at the latest, after Gaza broke the art world (Velasco), the upcoming discussion should be devoted to a retelling of recent art history and to searching for infrastructural relationships that can give space to the intimacy and intellectuality, the passion and sensuality of art in a self-determined way. It is time for a self-critical assessment: can we in the art scene really still assume that we live in the best of all possible (state-subsidized, highly professionalized) worlds? Can we only fight to preserve our vested interests? Shouldn’t the discussion about inclusion and exclusion concern not only the “others,” but above all our own systemic narrative? What trap have we fallen into? What went wrong? Do we also work with double standards and hypocrisy? Should we re-read and reinterpret our own past, that of the so-called rehabilitation of modernism after fascism and during the Cold War—as was done, at least retrospectively and to some extent, with Documenta2?