In Gabriel García Márquez’s world-renowned novel Chronicle of a Death Foretold, the reader knows from the very first page that the story will end in murder. Furthermore, this is not just an intuition. The author reveals in the very first sentence that the main character, Santiago Nasar, will be killed. Yet, the author’s narrative is so clear, and the language of the book so fluent, that despite knowing the ending, the reader continues to read with great curiosity.

Evaluating elections in Germany, unlike in many other countries, is often like reading Chronicle of a Death Foretold. Polls have a low margin of error. Political developments and candidates’ speeches from the parties already give away what the election results will be. Therefore, most of the commentaries on the state parliamentary elections in Thuringia and Saxony on Sunday, September 1, had already been written the previous week and had already reached the editors. The only thing missing from the articles on the editors’ desks were the election results, and there was an unoptimistic hope in the language that made one wonder “what if?”.

Just as we know Santiago Nasar will be killed in Chronicle of a Death Foretold, voters also knew that something would “die” in these elections. However, in this environment, both excessive hope and despair are meaningless. A good analysis of these two elections could revive some of the “things” that seem to have died in Germany.

The rise in support for the far-right AfD (Alternative for Germany), especially in eastern German states, was predictable. The initial results confirmed this: in Thuringia, the far-right party came in first place with a 6% lead, while in Saxony, they came in second by a narrow margin. It was also clear that the party surpassing AfD in Saxony being the Christian Democrats (CDU) would not make anyone on the political left happy. While a coalition between CDU, BSW (Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance), and SPD (Social Democratic Party) was expected in the Saxony parliament, in Thuringia, the only way to form a majority government would be for all the parties, except AfD, to agree on a coalition. The CDU had said they would never form a coalition with Die Linke (The Left), while it was known that Die Linke’s stance toward BSW wasn’t very positive either. In a minority government scenario without one of these parties, AfD could tie the hands of the parliament on matters such as the dissolution of parliament in extraordinary situations or the appointment of judges to the high court.

At this point, rather than being anxious about AfD’s rapid rise, it’s important to focus on understanding the reasons behind it. This is the only way to see the light at the end of the tunnel in the fight against far-right radicalism.

Wars and economic crises have left more than just bloodshed in world history. Far-right radicalism has always emerged as the rising tide in times of such crises. The crisis that began with the Ukraine-Russia war deepened when Germany, with an industrial-based economy, lost access to Russian gas. Inflation soared to levels not seen in a long time. The burden of taxes weighed heavier on citizens than ever before, and wage increases failed to keep pace with the rising cost of living. The ongoing housing crisis intensified. The social injustice between East and West Germany, combined with the government’s shifting budget from social services and education to defense, made the rise of far-right parties inevitable, especially those that based their politics on fundamental rights. These parties, with unfounded arguments, blamed all the existing problems on immigrants, denying Germany’s imperialist past and the fact that these issues existed long before the waves of migration. However, by presenting a tangible “enemy” and an immediate “target” to the impoverished masses, they garnered attention and successfully secured the votes of this segment of society.

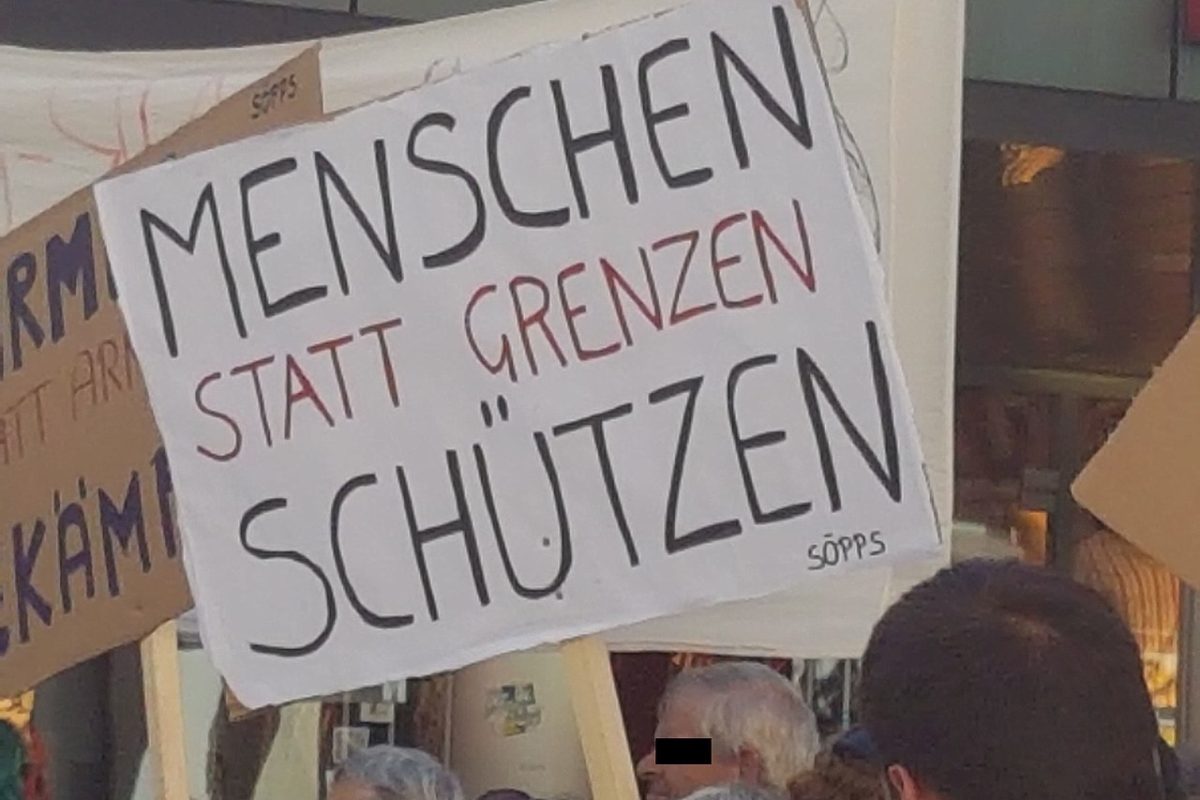

At this stage, liberal parties with vague rhetoric, often criticized for being unclear, began to gradually lose the support they had found among voters. Parties that focused on the core issues of the majority, namely the lower-income groups, and that had clear principles, whether good or bad, started to rise. The existence of a left-wing party that centers around fundamental issues like peace, social justice, housing, and food security would be one of the most effective ways to prevent people who wish to oppose the detached and indifferent policies of the current federal government from being forced into the arms of the AfD.

For now, no party is willing to form a coalition with the AfD, which shows that there is still time and leverage to allow the development of the type of left-wing movement described above. It must be emphasized that the right to a decent life and social justice are the most important values for everyone, and that the poor people who voted for the AfD but are not part of the core of the party must also be convinced of this. Because without them we can never resurrect the “things that have died.”

This article was originally written in Turkish. Translator: Gülşah Gürsoy