Those who live near Dresden (two hour train ride from Berlin) and who are interested in the art of the GDR – should try to catch the exhibition Globale Kunstgeschichten in der DDR. Unfortunately it closes on 2nd June 2024, but you still have time. Berlin Left has previously carried articles on DDR Art, and aspects of socialist art. This article simply aims to alert nearby readers, and to highlight this exhibition, and some of the works.

The range of the art included here is broad and it covers a wide range of styles, or forms. From those works patently in the mould of what is known as socialist art – to more abstract forms.

But regardless of exact form, the exhibition’s purpose is to show the internationalism of DDR art up to the time of the fall of the DDR. Of necessity then, it contains vivid replays of major past intense class struggles. From Guevara and Castro’s Cuba to Allende’s Chile, from the Vietnam war of national liberation to Palestinian oppression. But if anyone pays attention, these are of course not just ‘past’ struggles.

Perhaps to emphasise a ‘current-ness’ to the exhibition, a graphic of the Communist Manifesto by Lea Grundig is prominently displayed. This is either at the end or the beginning of the display – depending on where you start. Alternatively, you could easily believe that the curators here are being slyly provocative – As if to say ‘What of all this “Communist Manifesto’ now?” Below is a single piece of a four image set.

That a cynical curatorial perspective may have been intentional, is indicated by signage at the exhibition. This notes that Lea Grundig (1906-1977) was a prominent establishment figure in the DDR art world, and she was able to travel extensively in countries with links to the DDR including China and Vietnam. This is contrasted to the inability of non-approved artists to travel. Her Wikipedia link is informative, but none of that detracts from her artistic merits. Moreover her past as a victim of Nazism, and as an early communist anti-fascist is I believe given no attention in the exhibition.

Moving towards some of the world links that are made in this exhibition, several countries are referenced. I only touch on a few of the most memorable to me. One such marked the murder of the first elected Prime minister Patrice Lumbumba of the Congo. He was murdered in 1961 by agents of the USA. The USA supported the pro USA comprador President Joseph KasaVubu, and Lumumba’s successor as Prime Minister Moise Tschombe. The erstwhile Belgian Congo was engulfed in civil war.

Lomar displayed the backdrop of a civil war –The left panel shows and the German mercenary-soldier Major Siegfried Muller (aka ‘Congo Muller)’ who always wore his Wehrmacht Iron Cross, the Belgian mercenary Leutenant Mazy with a banker, consorting with prostitutes,. In the centre section a decapitated and crucified black corpse bleeds out. On the right panel is the widow Pauline Opango Lumbumba who shirtless – led a Protest March to the UN headquarters.

Let us leap to 1973 and re-visit Allende. Christoph Wetzl (born 1947-?) shows him slumped dead in a presidential chair that is shot through, wrapped in the Chilean flag. It is true that Allende in a hopeless situation shot himself, but this is quite besides the point. This picture is in the permanent collection, but you won’t find the next one there.

That is by Hartwig Ebersbach (B 1940) entitled ‘Widmung an Chile’ [Dedication to Chile]. This draws for inspiration on the famous photograph from the 1871 fall of the Paris Commune of the dead communards who were shot down. They were lined up to be photographed by the military.

Vietnam, Palestine and other zones of imperial destruction are all present in the exhibition as well.

But lacking space, we will move to another feature in the exhibition. That is the refuge and learning the DDR certainly provided to some artists of the colonial and semi-colonial world. I here choose a very expressive self-portrait by the Iraqi Sami Hakki with a red flag. He was a student at Dresden Academy of Fine Art. It does not say in the exhibition what happened to him in later life. But there are a number of video interviews with many artists from the colonial world who obtained artistic training in the DDR. Some went back to their home countries, but some stayed in the DDR.

No doubt for self-serving reasons, the exhibition also notes the calculated abuse and exploitation of the DDR itself, in its dealings with the proletariat of the colonial world.

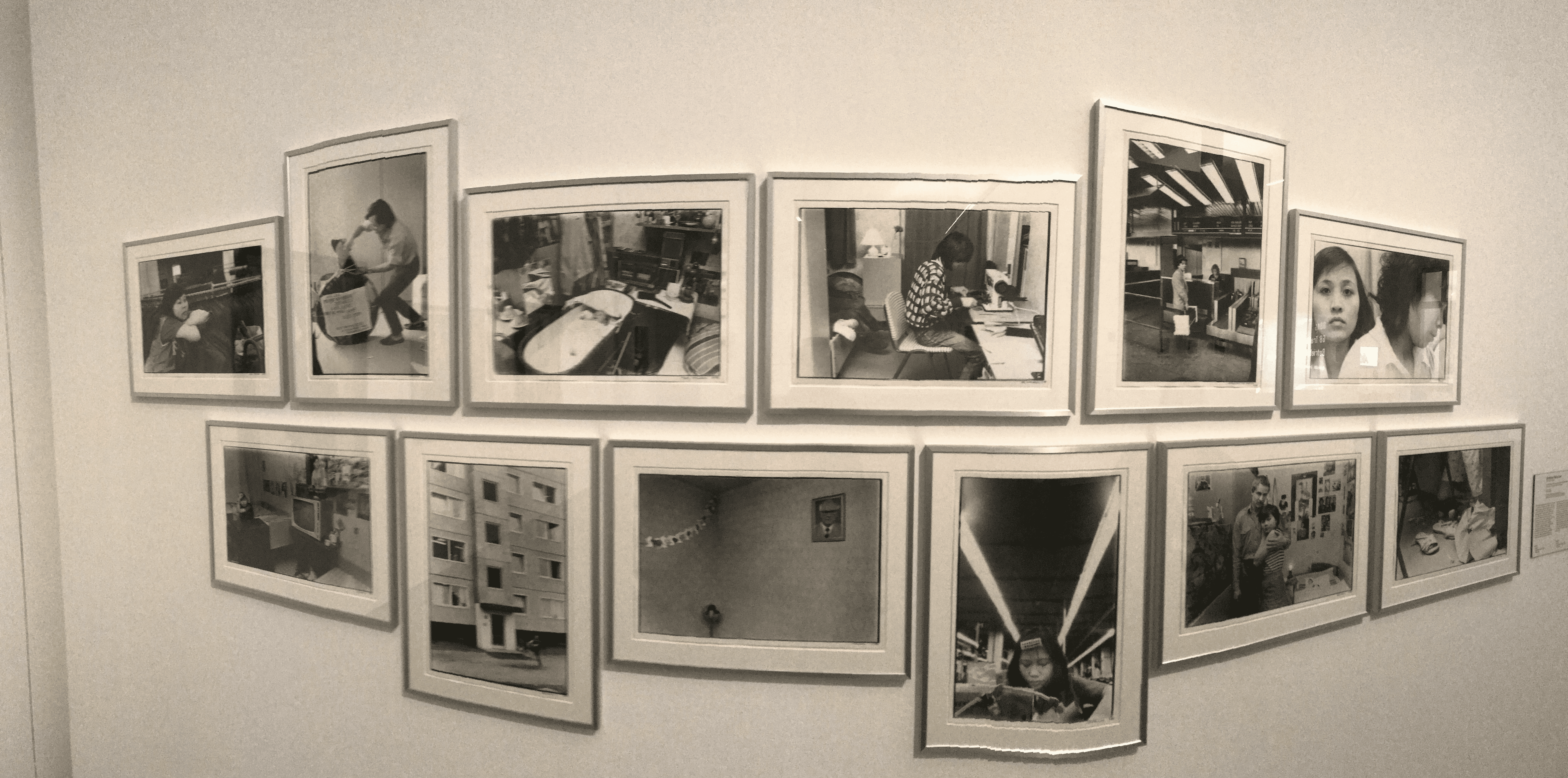

But for all the potential ulterior motives, it cannot be denied that the DDR was an exploitative state. For example witness the circumstances of the Vietnamese workers who were brought to the DDR to work and who often lived in appalling conditions as a super-exploited fraction of the DDR proletariat. From Mattias Rietschel (B 1958) is shown a series of photographs of Vietnamese workers in Dresden. Along the way are various illustrations of how harsh the DDR bureaucracy was in enforcing strict visa laws on some of these foreign workers.

Finally let us move to a special case which is still with us in a very real way. That is the case of Cuba. It is not necessary to get into a long debate about whether or not it ever was a socialist state. I will state my belief that it never was such. Here it is only relevant to say that an early depiction of now familiar images of Che and Castro, were accompanied by some more evidently critical works. Whatever the motivations of the curators, these show originality and verve.

For example, the work of Tonel (Antonio Eligio Fernandez) (B 1958) entitled “Lenin, Was tun?” from 1991. Here a small 3D bust of Lenin is frowning on a beach, frowns as he watches 3 tourists enjoying Cuba’s beaches. Indeed – “What is to be Done?”

In conclusion, regardless of whether you believe the state of the DDR was socialist or not, it certainly became a forum for some very important and moving art to develop. Whether all of it can be considered under the rubric of “socialist art” is a matter to be discussed in a further piece. But this exhibition is very worthwhile. And this was the aim of this short piece. If you can – go and see it. Or else the catalogue is E19.80. While you are there, the new gallery of the Albertinum has in its permanent exhibition some masterworks from the DDR, but more at another time.