Ruth Wilson Gilmore and numerous other abolitionist thinkers and activists identify the penal system’s central role as a necessary instrument in upholding a capitalist system. So-called ‘organised abandonment’, the systemic giving up on and neglect of people by the state, is an integral part of the penal system. When people lose their jobs, are thrown out of their homes or stuck at borders without documentation, their destinies are not isolated, but rather intertwined with the penal and regulatory systems that specifically limit the choice in action of those affected.

Institutions of ‘justice’—the police, courts and prisons, among others—enforce, regulate and administrate organised neglect.

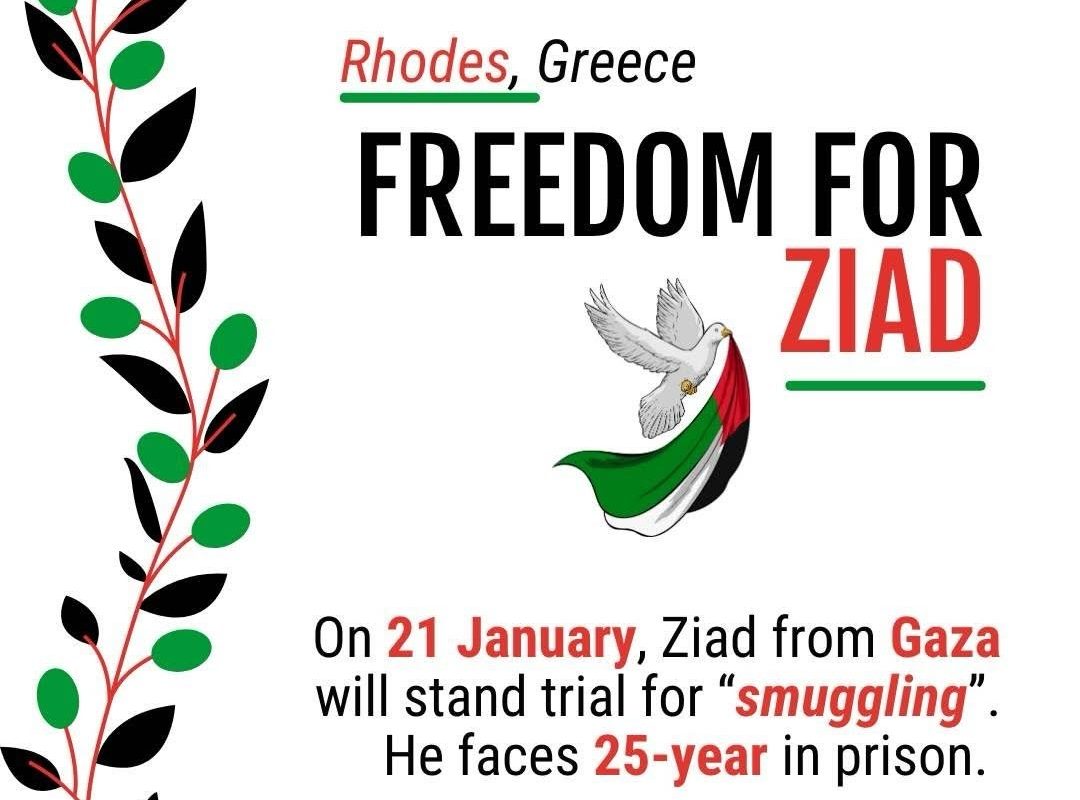

The interlocking and mutual support these systems share is apparent in Homayoun Sabetara’s case; on August 25, 2021, after having fled Iran he was arrested by Greek police after crossing the Turkish border by car. His escape was meant to lead him to Berlin where his daughter lives. In a process that only lasted two hours, he was sentenced to 18 years in prison for human smuggling on September 26, 2022. Since then, the 63-year-old Sabetara has been in prison in Trikala, Greece. Relatives, including his daughter Mahtab Homayoum, began a campaign called ‘Free Homayoun’ demanding his release and supporting him in his appeal process. The process ended on September 24th with a sentence reduction to seven years and four months. The court expressly recognised that Sabetara had not acted with the intent to profit and that there was no legal path of entry by which he could have reached his daughter.

Isolation and False Security

The means of fighting so-called human smuggling, in which Homayoun has been caught, are part of an overarching European anti-migration policy. Embedded in this fight is a falsified debate about security; the ‘safety of one’s own people’ is constructed by deportations, Duldung [status preventing people from working], and the simultaneous criminalisation of migrants and massive investments in border protection companies such as Frontex.

The aim of such sham debates is to transfer systemic failure to the individual level and thus uphold the existing system by justifying a new definition of security. This security is not achieved through meeting fundamental needs like access to housing, food and clean water, participation in society, education and medical care, but rather through more police and fortified security checks. In 2023 alone, The European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex) is said to have invested 845 million euro in these measures.

Those who happen to be at the wheel of a car with illegalised migrants in it when it is stopped by police is deemed the smuggler. The witnesses are other passengers or the intercepting police officers. This was also true in the case of Homayoun Sabetara. The charge against him was based on two witness statements—one from a police officer and one from a passenger in Sabetara’s car, which were taken upon arrest without a translator. These proceedings are not an isolated case. Harris Ladis, the lawyer defending Sabetara, described the police’s conduct as such: ‘The police make no attempt to cross examine or investigate witness accounts. To avoid too much hassle, they generally take a statement from just one passenger, who says, ‘‘He was driving when we arrived.’’ That’s enough to arrest someone and hand them over to the examining judge.’

Those who cannot sort out a lawyer for their trial don’t stand a chance in court when up against high criminal charges such as human trafficking, as in Sabetara’s case. His lawyer’s fees alone amounted to more than 15,000 Euro. Poverty means staying (longer) in prison.

The most frequent questions in court centred around Sabetara’s financial situation in Iran—what did he do for work? How much did he earn? The same questions were posed to his daughter. Did he send part of his earnings to Germany? How was she funding her life in Germany? How did her father pay for the journey? How much money did she send him? Did he have financial issues? Did he own a car? Or receive an inheritance? A house? So what about the house? Did he leave his possessions or the proceeds from the sale of his business behind? What did she study? Where did she work?

Defendants must constantly emphasise that they are not ‘poor’ or ‘uneducated’. Homazoun and Mahtab are no exception. In court they repeatedly had to talk about their careers and academic achievements in order to convince the judge that Sabetara’s detainment was unjust.

Research by Borderline Europe shows that court proceedings against so-called ‘smugglers’ have an average length of 37 minutes, while cases assigned to public defenders take 17. Borderline Europe’s shortest documented case was just 6 minutes long. These short cases are often unlawful and based on insufficient and questionable evidence, for example the statement of a single police officer or coast guard agent. In 68% of documented cases, those giving the statements were not even present in the courtroom. These proceedings decide destinies in a matter of minutes; on average, human smugglers are sentenced to 46 years in prison and fined 332,209 euro.

Homayoun Sabetara’s case also shows that prisoners must rely on help from outside the prison. They need someone who looks out for their care and health, procures needed medication and alerts the prison should they fall ill. Or someone to accompany them on their court date, send them money and offer support for their freedom. For those who have no one to see during visitor’s hours, prison becomes an even greater hell. Usually represented by a public defender, without an adequate interpreter, they are alone against a system that criminalised them from the beginning.

The tough sentences that most often affect young prisoners without relatives are meant to act as a deterrent. Alone and abandoned, those who have neither the social nor economic capital to defend their rights are the ideal victims to substantiate the European security debate—criminals tasked with maintaining the true face of a ‘safe’ Europe.

This article first appeared in German on the Anaylse & Kritik Website. Translation: Shav MacKay. Reproduced with permission.