“Thank you and go vote tomorrow, it’s important!” This is how one of the entertainers on the Social Democratic Party’s (SPD) stage, a young man with a guitar, ended his performance. Because I happened to be in Kassel in the run-up to the state election on Sunday, October 8, I had the chance to observe the Red Carnival that the SPD put up in the city’s central Opernplatz on Saturday. The SPD showing did dwarf the stands from which other parties accosted shop-goers in the area, but it did not live up to the hype. As I walked by, SPD leafleteers made up the majority of hangers-on and, on benches that could have sat around 50 people, only four or five listened to the performance.

All this stands to show how right the singer was: the elections on Sunday were important, especially for the SPD. In Hesse, the state where Kassel is the third-largest city, the Social Democrats have not been in government since 1999 (not that they haven’t had the chance: the SPD torpedoed a red-red-green coalition in 2008 because it refused to collaborate with the Left Party). In 2023, the CDU once again went up and the SPD went down.

West German politicians have long placed the blame for the rise in right-wing extremism on the supposed chauvinist-authoritarian legacy of the GDR.

But the biggest winners and losers are outside the CDU-SPD duopoly. Having first entered the Hessian parliament in 2008, the Left failed to reach the necessary 5% last Sunday and will have no members in the Landtag. While the Left lost all of its nine seats, the Alternative for Germany (AfD) gained as many. With more than 18% of the votes, the far-right party became the second-largest group in Hesse’s parliament.

Last Sunday was a double election day, and not to be outdone Bavaria elected the most right-wing Landtag in the country. The Christian Social Union (CSU, CDU’s Bavarian sibling) won, but with a historically low 37%, their lowest since the reunification of Germany. The AfD and the right populist Freie Wähler (FW) came out third and second, respectively, each increasing their voter share with over 4% since 2018. We might take some solace in the Free Democrats’ failure to get over 5% – but not too much, because most of their voters moved to the CSU, the FW, and the AfD. As one activist from the Munich initiative Offen Bleiben (Remain Open) declared for the taz, “These will be tough years.”

Young and Western

Perhaps the biggest surprise for the German center is that the AfD has escaped the East. And proudly so – Alice Weidel, the party’s co-leader, boasted that “AfD is no longer an Eastern phenomenon, but has become a major all-German party. So we have arrived.” While we on the left might know that Ossis have no inherent inclination toward extremism, West German politicians have long placed the blame for the rise in right-wing extremism on the supposed chauvinist-authoritarian legacy of the GDR.

Of course, history is much more complicated than that, and the present has proven it. The AfD has become an established parliamentary party in two Western states. Hesse is home to Germany’s financial heart, Frankfurt am Main – and, we should not forget, the home of Hanau. Bavaria is home to Gillamoos, the festival that Friedrich Merz declared the bastion of true, authentic Germany. But Merz was probably not happy to see that in Kehleim, the district where Gillamoos takes place, the CSU lost 4.7%, while the AfD and the FW won 3.6% and 5.4%, respectively.

Not only has the AfD made progress into the West, but it also broke new ground among young voters. AfD’s share of the votes expressed by Bavarians aged 18-29 was 18%, significantly higher than their overall result of 14.6%. In Hesse, the party even managed to overtake the Greens among 18-24 year olds.

Even if the mainstream parties will not join the AfD in coalitions, they do allow it to set the terms of appealing to the public. In other words, mainstream parties are meeting the AfD on its own terrain, or hoping to find the secret for its soaring rise and to steal its voter base.

Taking a page from the strategies of up-and-coming far right parties throughout Europe, the AfD has amassed a steady audience on TikTok, a platform ignored by the SDP and the CDU/CSU. But there is more to their success than memes. Young people continue to feel disenfranchised and see their perspectives becoming more and more limited. Young men especially turn toward the far right, who has easy answers and visible culprits to offer. Among voters of all ages, AfD is reaping the benefits of the federal government’s lack of social policies.

So what now?

At the end of the day, in Hesse and Bavaria, we get more of the same. More of the same government, first of all, because CDU/CSU’s position has not yet been challenged from the right and certainly not from the left. The CDU can continue their convenient partnership with the Greens in Hesse, or explore a GroKo with the SPD. The CSU seems to have no problem renewing their alliance with an FW led by the suspected anti-semite Hubert Aiwanger. A “strong and stable government” is what CSU leader Markus Söder believes this election delivered to Bavaria.

But more of the same does not mean a smooth and peaceful life. Because this last round of state elections brought new evidence (as if more was needed) that the rise in AfD support is not a fluke, but a steady trend. Week after week, new opinion polls show the far-right party cementing its second place. In some elections, they even come first, like in the Thuringian district Sonneberg, led by an AfD member, or in Raguhn-Jeßnitz, a small town in Saxony-Anhalt, which made the news by electing the first ever AfD mayor.

More of the same then, means that new taboos and checks set up against the far-right in Germany keep failing. In July, CDU leader Friedrich Merz declared (and then quickly backtracked on) his openness to collaborating with successful AfD candidates. The pragmatics of local administration, Merz insisted, will force politicians to work together with fascists. Moral considerations are not enough to maintain the famed “firewall” between AfD and mainstream parties.

The separation seems particularly vulnerable to class interests. In Thuringia, CDU only managed to pass a reduction in real estate property taxes with parliamentary support from the AfD. Little does it matter that the Thuringian AfD is under observation by German intelligence services for right-wing extremism. It is also led by none other than Björn Höcke, who, at the time of the vote in September, was just beginning his trial for using Nazi slogans during his campaign.

If the Thuringian vote was the first crack in the firewall when it comes to policy-making, the political space has been tilting more and more right. There is no firewall when it comes to discourse and debates. Even if the mainstream parties will not join the AfD in coalitions, they do allow it to set the terms of appealing to the public. In other words, mainstream parties are meeting the AfD on its own terrain, or hoping to find the secret for its soaring rise and to steal its voter base.

Anti-Migrant sentiment in the driver seat

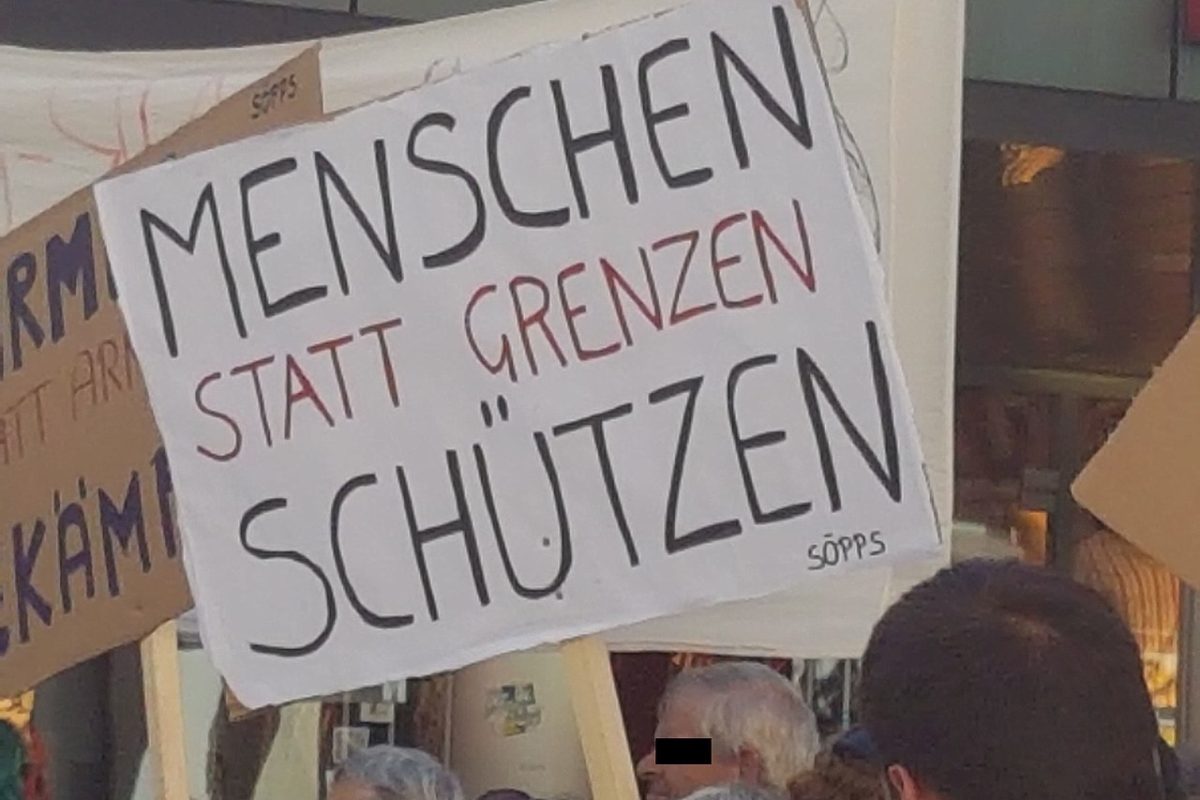

The first thing I saw when I got off the tram in central Kassel was a ver.di demonstration, but walking through the city I quickly noticed that the parties’ campaigns filtered workers’ demands through a different topic: immigration. On one of the city’s main boulevards, an AfD billboard sporting the slogan “We set borders!” was accompanied by a smaller poster with a more sinister message: “Deporting illegals creates housing space.”

The FW also appealed to Hessians’ anti-migration sentiment, with a messaging just slightly more respectable than the AfD, but not different in nature. Orange posters with the message “Migration: Those who want to work are welcome” followed me through the city-center. It seems that their campaign slogan, “A Hesse for all,” should be taken with a pinch of salt. At any rate, Hesse is not yet the place for the FW. They obtained only 3.5% of the vote and failed to further consolidate their position of not being just a Bavarian party, after entering the Rhineland-Palatinate parliament in 2021.

Their approach worked better in Bavaria, where they came second with 15.8%, up 4.2% since the last elections. Shortly before the vote, when Friedrich Merz was criticized for imagining refugees who receive free dental treatment, Aiwanger came to his defense.

There are “many people who are in our social security funds or who have access to our social security funds and medical care who cost us a lot of money,” he declared. We need to “simply not let so many people into the country.”

CSU leader Markus Söder, in turn, announced his intention to stop cash support for rejected refugees in in Bavaria and to lower refugee financial support overall.

And Bavarians believed in all of this. According to Tagesschau polls, migration was the second most important election topic, after economic development. But the two are closely connected – immigrants are one of the causes that people find for ongoing crises and hardships. There is little truth to that, but 98% of FW voters agreed that immigration and asylum laws should be changed so that fewer people enter Germany, more than AfD’s 95% and CSU’s 89% – but what difference do these few percentage points make when 83% of all voters agree on this issue?

In Hesse, climate and energy were the second most important topic for voters. But the Greens, undercut by a tabloid campaign about the boiler law, failed to emphasize the social aspect of their policies. That’s not to say that migration didn’t matter. The average agreement on restricting immigration and asylum is lower in Hesse than in Bavaria, at only 72%. AfD, CDU, and FDP voters, however, all score 90% or more. This was the winning ticket for the Hessian CDU. Boris Rhein, their top candidate, built his campaign on proposing stronger borders and more facile deportations.

Now the SPD is trying to catch up. Federal Interior Minister Nancy Faeser was the party’s top candidate in Hesse, where the shameful 15% result led to calls for her resignation. In the past, Faeser accused Rhein of being too cozy with far-right extremists. But condemning extremism does not win elections, a lesson the SPD seems to have learned. Just a few days after the Hesse vote, Faeser announced a law project that would allow Germany to “deport and expel criminals and dangerous persons more consistently and quickly.” Meanwhile, SPD Chancellor Olaf Scholz met with Merz to discuss imposing an obligation to work on refugees, as demanded by the federal states.

Will the Left draw the same lessons from the Hessian elections as the SPD? Some of its members already have, and the rifts within the party will only be deepened. Just before the Left lost its seats in the Landtag, rumors about Sahra Wagenknecht finally leaving the party to found her own hit the news. Just afterwards, almost 60 of her colleagues demanded her expulsion.

What is certain, however, is that if the Wagenknecht party will make its entrance, its purpose will be to take a bite out of the AfD pie. And that will most likely come with taking a leaf out of the AfD’s book as well. In September, Amira Mohamed Ali, Wagenknecht’s ally and co-chair of the federal Linke fraction, came to the defense of the Thuringian CDU: “What were they supposed to do? Not introduce motions as opposition or withdraw the motion after the wrong people agreed with it?”

A sensible, procedural argument about parliamentarism, which however takes on more worrying dimensions when we account for Wagenknecht’s politics. The immiseration of the German working class, Wagenknecht holds, is caused by immigration and the influx of refugees. Less than a week before the Thuringian affair, the Neue Osnabrücker Zeitung published an interview with Wagenknecht in which she declared that migration must “absolutely” be curtailed.

“There are limits beyond which our country is overburdened and integration no longer works,” Wagenknecht continued, before bringing up more right-wing talking points about immigrants who teach religious hate, exhaust the social state, and disrupt education because they do not speak German.

After the elections, the main target during Wagenknecht’s fierce attacks on the federal government’s failures was Nancy Faeser. Was Wagenknecht condemning Faeser’s racist approach to policing so-called “clans,” perhaps? On the contrary, Wagenknecht took the opportunity to attack her as a weak interior minister. Faeser has supposedly “lost control” of migration and allowed the refugee crisis to become “at least as bad as in 2015.” We need stronger and stricter approaches. No better formulation than Wagenknecht’s own then; if it is founded, her party would be an alternative for AfD voters.

The great moving right show

In his 1979 article grappling with the rise of Thatcherism, Stuart Hall explains what the far right does to reshape ideological space. Even if not successful in its destructive intentions, the radical right still “takes the elements which are already constructed into place, dismantles them, reconstitutes them into a new logic, and articulates the space in a new way, polarizing it to the Right.”

Curbing immigration has also become a question of pragmatism, of protecting Germany not from foreign threats, but from homegrown right-wing extremism… We must appease fascism to stop it from becoming fascism.

Hall’s conjunctural analyses should not be taken as general lessons, applicable everywhere. But I believe that his formulation can help us make sense of the anxiety-inducing monotony with which the AfD has been appearing on the news. A few percent here, a few percent there: at some point we might be tempted to just turn away and let all of this be background noise. Or to say that it is happening just in the wrong places, just with the wrong people. But that would be a mistake.

The AfD’s rise is not a quantitative change, but a qualitative one. When the party comes second in an election, Weidel can confidently declare that the firewall is “deeply undemocratic”. In Bavaria and Hesse, “millions of voters are excluded” because millions of voters have democratically chosen a far-right party. We are living through a re-articulation and re-polarization of German politics. The AfD is dragging to the right our understandings of what is acceptable, what is necessary, what is democratically demanded.

The two elections last Sunday have been the jolt that some needed to realize this. But what the CDU/CSU and other parties seem to have realized is not the creep of fascism, but the truth of Weidel’s words. There are millions of voters who have left them. Millions they want and need. The way to beat the AfD is not to put up a firewall, but to take their place on the right.

After all, Markus Söder made it explicit. Having won his new mandate in Bavaria, he set the tone for his migration policies: “We perceive the AfD as a right-wing extremist party” whose approaches to migration are too harsh. But he also declared that tougher immigration and asylum legislation is nevertheless needed to stop AfD’s rise.

After the result in Bavaria and Hesse, the German right (and not just the far-right) has new wings – and more space. What Söder’s declaration shows is that they don’t need to only rely on law and order to justify their racism. Curbing immigration has also become a question of pragmatism, of protecting Germany not from foreign threats, but from homegrown right-wing extremism. It just so happens that doing so requires moving to the right. We must appease fascism to stop it from becoming fascism.

The AfD’s “exclusion from responsibilities of government is not sustainable,” Weidel predicted. With current developments, she is right. We might not see the AfD in governing coalitions, but we will see more and more of their policies and discourses. The AfD have not yet taken the system apart, but they are charting the system’s path.