13 August

Acceptance

The list of the accepted.

Name: Rasha Al Jundi

Date of travel: August 21st for 7 days/6 nights

This was the message that flashed across my phone screen from the Jordanian travel agent.

I don’t remember a time when I held my breath for so long ever before in my life.

August 21

Exclamation mark

“Do you have a weapon in your bag?”

This was the first question that the Israeli occupation border police officer asked me after inquiring if I can speak English or not. My positive answer to this latter question got him to exclaim with open arms to a hall full of people “FINALLY!” I was on a bus with approximately 45 other travellers, most of whom were elderly. We were the first “tourist group” of Jordanian passport-holders who were given approval by the Zionist occupation to visit our own homeland.

The irony that big brother imposes on Palestinians in exile continues with the performance of hypersexualized and condescending border control agents. I was in the middle of the queue to the first officer so I took my time to calm my pounding heart. It was the first time I come this close to the occupier. My heart beats and tense jaw reflected my rage, while my deep breaths reflected my control.

While I waited patiently for my turn, I examined the well-constructed hall at the northern Zionist “border” with Jordan. It is famous for being designed for tourists groups crossing by land, hence the fancy airport-like fluorescent-lit structure. My eyes darted from one corner to another taking in all the details, every camera, sign and tile. I took in the female agents with full makeup, well-manicured long nails, freshly styled hairdos and super tight jeans that accentuate their bodies. I took in the male agents with their tight t-shirts that show off their constantly flexing chest muscles. I took in every bark in Hebrew hurled at an old lady, every smirk, snort and snicker at anyone who did not place their bag in the correct way on the X-ray belt. I took in their stares and I stared back.

Questions flowed:

- What is your purpose for visiting Israel?

Tourism. - Where are you staying?

Metropole hotel. - In which city is it?

Jerusalem.

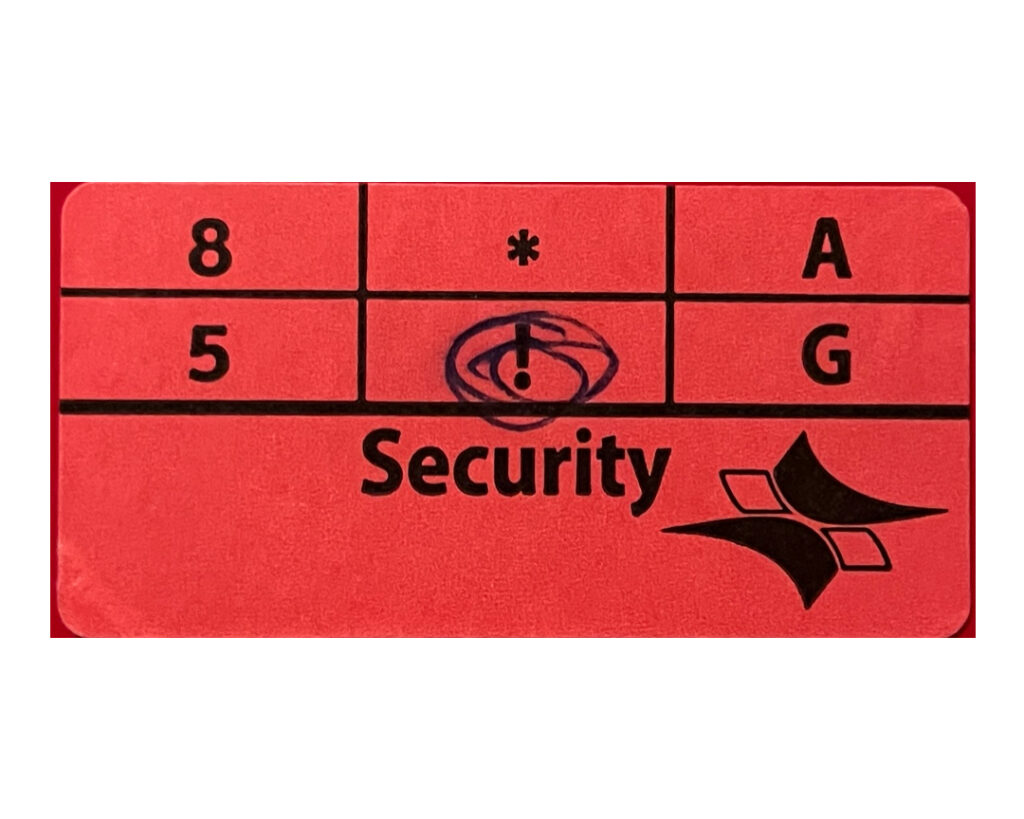

After a few more similar questions, a rectangular red sticker from a roll was slapped on my passport with the exclamation mark on it emphasised in blue ink. I was led to wait for a body search and after inspecting my bags, the passport control officer asked me the same questions in English before pausing at my grandfather’s name and wondering out loud, suddenly in Arabic: “Your grandfather’s name is Moses?” After some more waiting on the cold steel chairs, a cat showed up, sat in my lap and purred.

A female traveller fainted. She was Palestinian with an Israeli passport. The officers dragged their feet to respond while other travellers lifted her feet and sprayed water on her face. She eventually got up and was escorted to the seat next to me as she regains her composure. I handed her a small bag with a few left over nuts.

Another officer walked up to me, this time a woman, with a massive smile on her face. She greeted me as if we were long lost friends and proceeded to inquire about my work (being a photographer stood out the most), my place of domicile and eventually my permanent residency in Germany. The latter got me the needed nod to grant me the final entry approval by the occupier to my homeland.

Plan your death well…

“There is only one way for you to be allowed to remain here. It is – may God give you health – in the case of your death. But make sure to die in an Israeli hospital, ok? Otherwise, they won’t let you stay.”

With these words, the Palestinian guide ended his long list of rules. He attempted to lighten his persistent demands for us to not to even think of breaking the entry approval duration rules of seven days and six nights only. Our trip was already planned by the occupation before it has even started. The occupation’s approval wreaks of control. In addition to the duration of our stay, the dates of travel, the entry/exit points and departure time on August 27th were all already set by them. Israeli colonisation of Palestine is “ingenious”. It does not only occupy our land and minds, it also occupies our time.

For travel agents to guarantee that Jordanian passport-holders are bound to leave:

Occupied Palestine on the designated date, they get a close next of kin for each one of us to sign on financial guarantees that range between 25 to 30 thousand Jordanian dinars. I couldn’t help but wonder: is the “penalty” to return to Palestine equivalent to the cost of the majority of new vehicles that clog the streets of Amman? This is probably why, after receiving the occupation’s blessings to smell our country, our passports are collected by the Palestinian agent who receives us, leaving each one of us with a copy of the original and the flimsy Israeli green entry visa paper to move around.

Despite the loud and repeated instructions by the agent, the mood on the bus was one of pure happiness and joy. We made it. Many of us for the first time in their lives. Others for the first time since childhood. We were all glued to the bus’s windows. No one wanted to miss an inch of the land. Phones started ringing with excited relatives inquiring about our arrival times to either one of the two drop off points: first Jericho, second Jerusalem.

I had earlier decided to get off in the latter. After all, it is my first time home, so I had to see the heart of it. Surprisingly, after initially taking away my documents, the agent squeezed through towards my seat and handed me back my passport. For a second, the thought of staying back crossed my mind. Just for a second.

August 22

Fatima returns

A few months ago, a German friend travelled to the heartland of occupied Palestine to visit a friend of hers. She attempted to document my mother’s depopulated village Beit Dajan for me and shared the images she made on WhatsApp. The shock of how foreign everything looked on my phone screen stayed with me for several weeks. I could not show the images to my mother. I did not know at the time, that I will be making the same trip to Beit Dajan a few months later.

This time I confronted the ugliness of erasure myself. A block of identical houses sat neatly next to each other, with a school in the middle of the settlement, now called “Bet Dagan”. Nothing of the Palestinian identity was left in any of what I saw, except for an orange grove at the edge of this alien place. Fenced by grand Palestinian cacti, the land was beautiful and I heard my mother’s description of her grandfather’s groves in my ears. I asked the taxi driver to stop and wait for me as I stepped out and walked over to the fence. Luckily, I found a big enough dent in the barrier to sneak into the grove. I had planned a symbolic return for my late Grandmother Faima (Umm Ali), since my departure from Amman. With an embroidered purse that she made for me a few years before her death, my grandmother accompanied me throughout this trip.

I took the purse out underneath an orange tree and whispered to her that she is back home now. I will never forget the heaviness in the air, the smell of the orange tree leaves and the watchfulness of the cacti over me. At that moment, I reclaimed the Palestinian beauty of the land in Beit Dajan in spite of the Israeli ugliness. And I kissed the earth.

It was 17:45 when the bus parked near Damascus gate in Jerusalem. I remember the moment I stepped out of it. The sharp sweet smell of jasmine hit my nose and I looked up to realise that I was standing underneath a giant tree, decorating the fence of the Jerusalem hotel. Despite being located opposite a large bus station, the razor sharp scent took over. I smiled with relief. I was very anxious that the fist thing I will see and experience in the city is the extreme Orthodox Jewish presence. It was the rush hour for people to head back to their homes from work and universities. So I took my time on the side of the main road watching mainly Palestinians come and go from that neighbourhood.

The sun was slowly bending towards its exit for the day. A pleasant breeze caressed my skin and hair. Jerusalem’s unforgettable air hugged me tenderly and welcomed me home.

Visiting Yafa and Haifa was equally difficult. Western structures and standards of capitalist development have taken over both cities and pushed the few Palestinian community members into tiny cantons. I struggled to reconcile the views of the Israeli and other tourists posing for photos by the old Yafa port. Scenes of the old city scape from the latest book by Suad Amiry “Mother of Strangers” [1] came rushing into my head as I walked around the clock tower square. After successfully finding a Palestinian place to grab a cup of coffee, I asked the driver to take me to Al Manshiyya quarter.

“It’s all gone,” he said, pointing to the last standing proof of its existence, the Hassan Beq mosque. Surrounded by endless cranes, the mosque sits in the middle of what the Zionist entity wishes to develop into a central business district in Yafa. As Al Manshiyya was really a bridge of commerce between the port and Tel Aviv, colonisers are not wasting time in transforming it to an actual link merging Tel Aviv with Yafa to become one. The Palestinian Arab identity was completely scrapped into rubble, which nowadays forms the basis of a park on the side of the road. “They now call it the Oasis of Justice,” the driver smirked. The irony of that fact made me feel like a character in a new book. Unfortunately though, it would not have been a fictional one.

Despite my rage at the ugliness and strangeness of the “Mother of Strangers”*, I could not leave Yafa without feeling the the sea. Our sea. So I spent time floating in the Mediterranean, which hugged me with its warm August waves and welcomed me home. I have visited the same sea countless times before and lived by it in Tunisia for two and a half years. Yet, the water felt different against my skin this time around. I reclaimed my right to the Yafa sea.

The Boys of Akka

I felt like there was a heavy weight on my chest after stopping in Haifa and seeing everything in between as we drove though the Zionist entity. As I stepped out of the taxi in Akka, I felt that weight lifting. Zaki Nassif’s “Ya Ahiqata al Wardi”** filled up the air of the parking lot, as a lone cat rummaged through the overfilled municipal trash bin and people shuffled slowly towards the nearby Al Jazzar mosque. Shopkeepers shouted greetings and jokes to each other. The smell of cigarette smoke combined with shawarma and the salty sea filled the air. The sights and sounds of Palestinian stubbornness lightened my pace. The city’s mighty high walls cradled its stone houses, which are beautified by pots of flowers and cactus. I instantly fell in love with Akka.

After one of the best seafood meals at Abu Christo, I made my way through the city to check out the young boys who are famous for jumping off the city wall into the sea. Hussein, Abdallah and Mohammed greeted me enthusiastically. “Do you want to jump?” one of them exclaimed in my direction. They did not shy away from inviting other passersby or spectators from joining them. They regularly scale the thirteen-meter-high city wall to perform acrobatic jumps throughout the afternoon until sunset.

While I spent time documenting their stunts and enjoying the excitement of their youth, I couldn’t help but notice the floods of young Jewish visitors who flocked the city in religious groups. I was not sure whether those groups were from within the Zionist entity or from abroad. I watched a young Jewish girl break away from one of them and pray against the city wall. When I circled back from watching the boys to where she was, about an hour later, she was still in the same position. To her right, I noticed a kind of arcade boxing game that stood there unused. She couldn’t be more than fourteen years old. Yet her life as a future Israeli Jewish settler has been paved for her. She will end up here, perhaps even taking the place of one of the Boys of Akka, and claiming that she was here first. I stopped and looked hard at two adjacent yet very different scenes of youth and I wished I could go up to her and say “Play girl, don’t pray”.

23 August

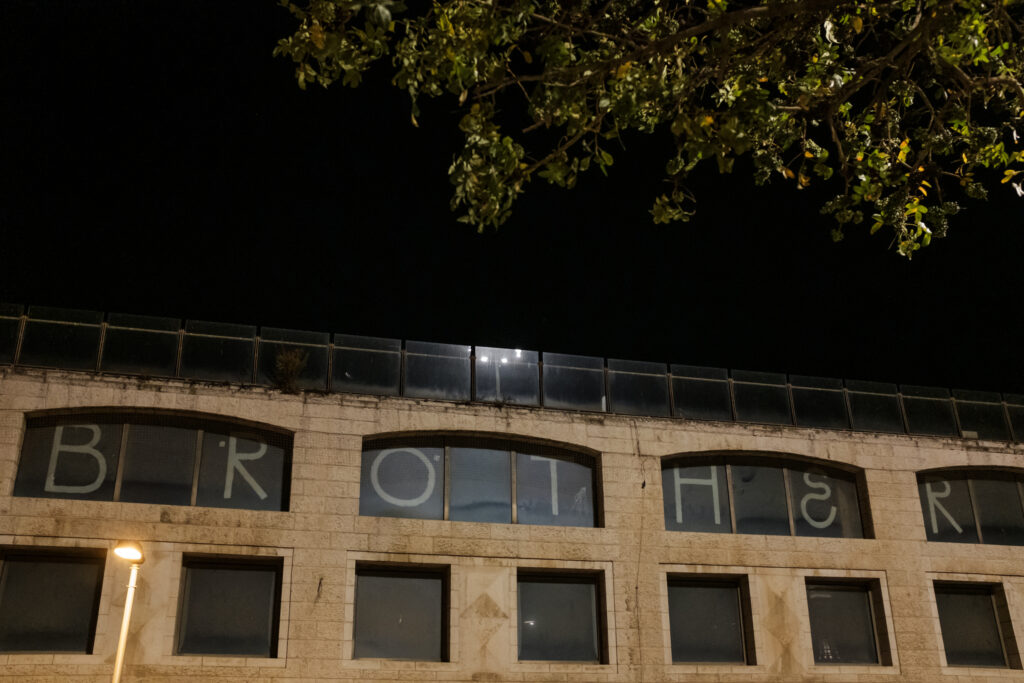

Big Brother

The Israeli occupation manifests itself in everything that is ugly in Occupied Palestine as a whole and in Jerusalem in particular. I always thought that George Orwell’s novel 1984 and the idea of Big Brother that it presents was a mad fantasy. Until I met the Zionist entity. The obvious crime that the occupation commits on our land from the Annexation Wall to settlement expansion, extensive surveillance cameras on every corner and underage religious Jewish settlers strutting around Old Jerusalem showing off their heavy M16, are all one form.

The hard truth sneers at me from every direction.

What the Zionist Big Brother also does so well, in a subtle way, is the rewriting of the place’s history. Does one pay attention to the newly planted star of David in the ancient tiles of the city’s walls? Does one marvel at the beauty of a creeping green leafy plant on the facade of Damascus gate, only to realise that this plant is a colonial tool to hide any Islamic appearance from the city walls?

Religious tourist groups roaming the alleys of Jerusalem surely don’t pay attention or look closer. They don’t see the occupier’s soldiers at every gate of the Al Aqsa Mosque compound inspecting Palestinians for their IDs so they can go in and pray. They don’t see the surveillance that profiles everyone, including them. They don’t see children with guns. They don’t see Big Brother. They only see stones. Those that they believe are the holiest truths, that they crossed miles across skies and seas to see, touch and whisper ancient phrases against. They don’t see the people of the city, its original inhabitants. The ones who are holding the fort against every colonial Jewish attempt to erase their kind and replace them with a foreign looking one. I have never despised tourism more than religious tourist groups in Jerusalem and their unholy conduct.

24 August

Ghosts & Ghettos

The first time I heard about Al Shuhada street in Hebron city that is notorious for settler attacks against Palestinian residents was more than ten years ago. I did not imagine, at the time, that I will be standing in the same street, a decade later, looking up at its wired metal rooftop that is littered with trash thrown by Israeli settlers aiming at Palestinians underneath. It is without doubt that the ugliness of the Zionist Big Brother reaches its peak in Hebron.

Despite its expanding neighbourhoods and lavish homes that reflect wealth and the tacky taste of the rich, Hebron’s old city was one of the saddest places that I visited in occupied Palestine. Walking through its deserted alleys and homes, I can only imagine how vibrant it must have been before the cancer of Zionism infected it. I can hear children playing around every corner, their laughter filling the air. I can see ghosts of women and men crowding the alleys with their shopping bags full of pickles, olives and sweets from the market place. I can hear vegetable and fruit cart sellers announcing their prices out loud for stay at home buyers. I can see the lights of the old city at night, keeping everyone awake until the late night hours.

What greeted me was the hollowness of the alleys. What remains is the shell of a city that was once the heart and core of commerce and trade in occupied Palestine. Doorways covered in intricate cobwebs. Multiple story households emptied of memories. The occupation dissects the city in half with a concrete wall and barbed wire. It literally created an underground Palestinian ghetto with an overground Jewish presence. The consistent invasions of the old city and the settlement expansion through it drove many of its original Palestinian inhabitants out seeking better living and work conditions. After old Jerusalem and Akka, seeing Hebron was like mourning a dear loved one.

“Are you Muslim?” asked the redheaded Israeli soldier who sits inside an air-conditioned glass box at the guarded entrance of the Ibrahimi Mosque.

I nod and move on through the second metal gate. Cameras point at me in every direction, as I step into the mosque’s courtyard towards the women’s toilets to perform wudhu and change into my prayer clothes. Another wall dissects through the mosque and cuts it in half. Just like the city that hosts it, it is dismantled and divided to create a ghetto within the ghetto. Every Saturday, illegal Jewish settlers are known to invade the mosque’s grounds and are allowed into every corner of it. They dance and perform their fanatic rituals around Abraham and Joseph’s tombs. Similar to Jerusalem, the site of a Turkish tourist group admiring the stones of those tombs gave me the chills. When they started to rub their hands against what they can reach from those sites and close their eyes in meditation, I cursed every tomb and every worshipped stone in Palestine.

Remove them all, together with those intruders on our land.

Martyr memorials

I have always wondered when we will be able to have a memorial to commemorate our martyred people, until I entered Nablus’s old town. Walking through it is like walking through a live martyr memorial of sorts. It is constantly updated with new images of the newly killed every week. Martyrs are everywhere, like the living dead: on coffee carts, pendants, shop signs, monuments, restaurant halls and household walkways. Most are standing tall, smiling. Some are holding weapons, others not. Youth splattered all over the city’s walls, watching over us and reminding us all of our losess and wins. A fresh breeze caresses the flag of the “Lion’s Den”, the infamous armed resistance group that started off in Nablus. The city is obviously proud of its martyrs and the blood it has been spilling to water the Palestinian earth. Yet I cannot help but question if any of those young men yearned to liberate the whole land? Or was it the absence of hope that pushed one to choose a death to be remembered by? It is a well known fact that the Palestinian Authority’s collaboration with the occupier has quashed any organised Palestinian resistance movement.

I faced the hard truths and questions on my own. I guess we all yearn for the time of the organised resistance movements of the past. Perhaps those young martyrs wished for the same thing.

On the road with the coloniser, everything that I had read and heard about the occupation in books, lectures and talks was being laid out right in front of my eyes. The sprawling and expanding settlements on hilltops looking down at Palestinian ghettos. The paired snipers standing against each other’s backs in a ready to shoot position at every passing Palestinian vehicle. The watchtowers at checkpoints with their advanced remote controlled automatic rifles. The roadsigns plastered with posters of the so-called “Jewish Messiah”.

The endless bulldozers, cement blocks, walls and bridges ravaging the land. The congested Palestinian cities that are eating away at what remains of their enclaved landscapes to expand. The carnage that is ripping away our existence as a population.

August 26

The Land Speaks Arabic

On one quiet late afternoon, I sat on a hilltop in Beit Jala contemplating my visit and admiring the vast and beautiful landscape. The space I was in was ideally located to block any views of Israeli settlements. It gave me an hour of peace. I took a few steps down the hill to an olive tree and noticed its new branches springing up from its base. I realised that during my trip I saw the vine tree creep through the walls; the fig tree drape over the barbed wire; the cacti spread over our ruined villages. The land is fertile with Palestinian blood and bones.

If we are all gone, the land will continue to resist the cement, the bulldozers, the settlements and the road construction on its own.

August 27

Exit Wounds

“Do you have a weapon?”

The question that the Zionist entity greeted me with upon my entry is laid out again in front of me. This time, however, to a fellow passenger on the bus at the Sheikh Hussein crossing into Jordan. The Israeli officer stepped onto the bus and selected a passenger at random to ask him this question. Due to his badly pronounced Arabic word for “weapon”, the passenger did not understand the question until we all shouted out the correct pronunciation at him. We just wanted to move on. A simple “No” followed by a smirk was enough to get us going. I remembered what the Palestinian agent told us a week earlier as he wished us a good trip:

“Remember, this is the state of the one soldier, not the rule of law.”

The air on the bus was heavy with sadness and frustration. Seven days and six nights were a fleeting moment in a sweet dream. One passenger took out his frustration at the agent, while another started crying as he recited the traveller’s prayer in the microphone for everyone else.

As the man sitting next to me started sharing anecdotes from his family visit, I did not hold back my tears as I listened attentively to him. He silently handed me a napkin.

I cried that this was my first, very short-lived time in the homeland and it could be my last.

I cried for the love that I lost in Palestine.

I cried for what could have been.

I cried because I did not want to leave.

But they did not want me to stay.

Footnotes

1 *Yafa city was nicknamed “Mother of Strangers” by its Palestinian inhabitants, as it was known to welcome any visitor or “stranger” to it.