Hi Zoë. Thanks for talking to us. Could you briefly introduce yourself?

My name is Zoë Claire Miller, I am an artist and organizer. I’m also one of the two spokespersons of the bbk berlin [berufsverband bildender künstler*innen berlin], which is Berlin’s visual artists’ union. I’m part of the board, which is composed of artists. It’s a honorary, elected position as opposed to a job.

The bbk berlin is one of the oldest and one of the largest artists’ organisations in Germany. We represent artists’ interests and work to improve their labour conditions in the city. We are also active in infrastructural terms, for instance bbk berlin’s subsidiary, the Kulturwerk des bbk berlin, runs printing and sculpture workshops. But a lot of our day-to-day work is around reacting to cultural policy in Berlin.

How many people do you represent? And how do you defend artists?

We have 3000 members. We do classic advocacy work – engaging with politicians and the cultural administration, trying to ensure that artists have a say at the table when decisions are made that affect them. Over the last decades a pretty good culture of dialogue was developed on the state level in Berlin. We ran successful campaigns for an increase in the amount of grants for artists, and the Berlin model of artist fees, which was a fore-runner to obligatory artist fees being introduced in many cities and states in Germany and Austria. The federal government is now finally making it an obligation that artists get paid in programs that they fund as well.

Berlin is an international city, especially in the art scene. How many of your 3,000 members are German and how many are international?

You know, I actually recently tried to find this out. But it’s not something that we ask when people join us, so we don’t actually have an overview. But I would say that our younger members are increasingly international, we can tell by the number of requests for information in English. Earlier, our membership was more homogenous.

There’s been a number of cases in Berlin, and in Germany, of artists getting into trouble because of their views on Palestine. How has this been discussed in the bbk berlin?

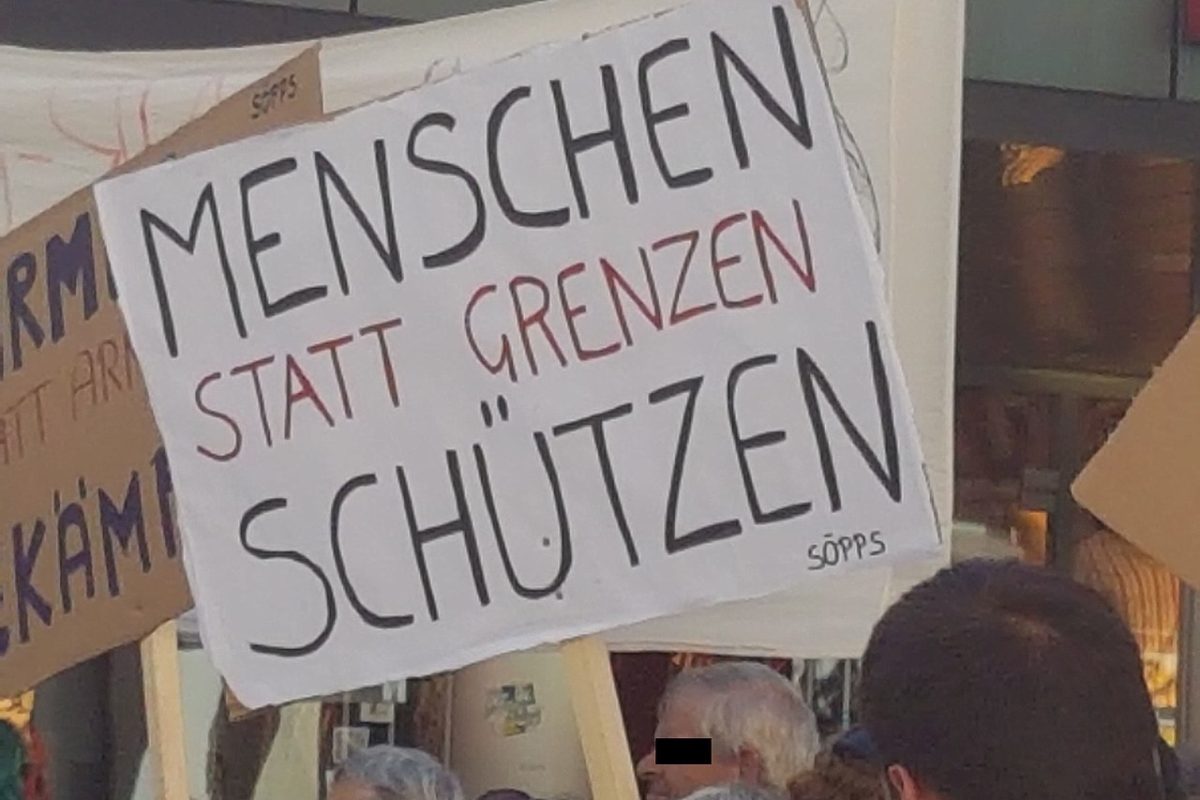

Within our membership and board, there are different perspectives on the issue. In general, we share a great concern for threats to artistic freedom and freedom of speech – and we are particularly concerned about the ongoing demonization of arts and culture and the atmosphere of fear it creates within our community. Discrimination over artists’ views on Palestine is a major issue, but discrimination directly or indirectly linked to the situation in Israel/Palestine and Germany’s involvement in it takes other forms as well. We have seen Muslim artists deplatformed over artwork featuring Muslim themes, Jewish artists being tokenized, and instances of discrimination running from racist microaggressions, deplatforming, silencing and censorship. This is not just coming from the right wing press and politicians, but also from some organisations that purportedly represent the interests of culture, notably the Deutsche Kulturrat [German Cultural Council].

The Deutsche Kulturrat was among the first organizations to push the narrative of a supposed “unbearable silence” within art and culture after the terrorist attacks of Hamas on October 7th. This unsubstantiated claim was effectively instrumentalized as “proof” that arts and culture are more antisemitic than the rest of German society. In reaction to carpet allegations of antisemitism, we looked into what kind of work is already being done within arts and culture to counter discrimination and specifically antisemitism, and where statements were released after 7th October. Many cultural institutions did in fact publish statements empathizing with the Hamas attack victims.

Beyond discussing and researching these questions, we provide legal consultation for our members with a lawyer, and we are planning workshops that help artists understand their rights when faced with discrimination. We recently joined forces with many other cultural organisations in concern over the legality and potentially discriminatory effects of the Berlin “antidiscrimination clause.” The clause was withdrawn – at least for now.

Could you expand on this? The last time we covered it on theleftberlin was in an interview on the day that the clause was withdrawn. What has happened since?

The clause was retracted quickly after it was introduced, after facing massive criticism. What was dangerous about the clause wasn’t just that it forced everyone receiving funding to adhere to the IHRA definition of antisemitism. This aspect was the most widely criticised, as IHRA is controversial on several levels, for instance how it is often weaponized, and is unsuitable as a regulatory tool. But the clause also placed anyone receiving funding under suspicion of funding terrorism and extremism. This amounted to the demonization of a whole professional sector, and seemed especially bizarre since a parliamentary inquiry to the Senate on whether Berlin cultural funding had ever been funneled to terrorism/extremism received a negative reply.

Another critical aspect was that the clause also contained a section requiring a sort of pledge of allegiance to Israel, thus endangering artists from many countries with authoritarian governments who do not recognize Israel, or excluding them from funding.

There are a few interesting updates on the clause. A Freedom of Information Act enquiry on www.Fragdenstaat.de produced files that evidence strong legal advice against the introduction of the clause. In-house legal counsel basically showed it was unconstitutional and unenforceable. A newer external legal opinion concurred, while exploring the possibility for the Senate to change Berlin law to enact a clause which wouldn’t just apply to culture, but to every type of public funding. This is currently the topic of controversial debate in the Senate.

We’ve talked mainly about the artists who you represent. There are other artists like Candice Breitz or Laurie Anderson who are not necessarily represented by you but still face repression because of their views on Palestine. Are you able to do anything with these cases?

We’re following the instances of censorship, the atmosphere of mistrust towards artists and fear among artists with great concern. Germany seems to be damaging its reputation as a liberal, open-minded and welcoming locus of cultural exchange. But as the bbk berlin, our main focus is Berlin.

Do you think there’s a connection between what’s happening in Berlin and what’s happening in the Arts in Germany as a whole?

I’m shocked and sad that some of the same provincial attitudes are displayed towards the arts in Berlin as in places in which culture is more marginal or sparse. You would think that in Berlin, culture wold be highly valued, because the city is so dependent on it, literally. It is one of the most important economic motors of the city. One would assume that politicians here would be attuned to the fact that freedom of expression is particularly important for Berlin, that our city is very international, and thus a diversity of opinions exists and is a blessing, rather than something to be repressed.

So I’m quite shocked, actually, that there have been statements made by powerful politicians here, that have an almost authoritarian, divisive and repressive ring to them than in small towns without an art scene. It’s also not just a governmental problem. The effects of the current atmosphere of fear of retribution and defunding are causing institutions to implement pre-emptive censorship, blacklisting those deemed or suspected to hold “risky” opinions.

You see the same pattern again and again of artists set to win a prize, take on a job, have an exhibition, or hold a lecture in Germany. Then right wing blogs, media or social media users comb the accounts of the artists, trying to find something that can be scandalized. They then fabricate a shitstorm, which applies pressure on institutions and politicians to denounce and drop the artist. I have also heard of cases where the second step is skipped – those with the power to create online outrage just go straight to institutions and threaten a shitshow, unless the institution cancels the artist. It seems just as challenging as it is urgently necessary to break this toxic cycle.

We just had the Berlinale, maybe the main cultural event in Berlin, where there were at the very least two shitstorms. First there was the invitation and uninvitation of AfD politicians. How did the BBK react?

We didn’t take an official stance on it, because film isn’t our our field. My personal opinion is that it was the right decision to disinvite the politicians, at least one of whom was a participant in a secret meeting plotting the mass expulsion of foreigners and German citizens. I don’t see how it is appropriate for those plotting the destruction of democratic principles to smile on the red carpets next to those they hope to deport.

Then, hot on the heels of the AfD shitstorm there was No Other Land. Did you get to see the film?

No, the tickets were hard to get, they sold out so fast. I am looking forward to seeing it soon.

Let’s try and recap what happened. No Other Land won the public documentary prize. Both directors – one Israeli, one Palestinian – made a speech. The German Cultural Minister Claudia Roth was caught on camera clapping, and she said she was only clapping for the Israeli director.

Both she and the Berlin mayor were sitting next to each other, smiling and clapping.

And then all of a sudden, the media and politicians are criticising the antisemitic directors who the public have falsely awarded a prize. Can we understand all this in the context of everything else which is happening in the Arts in Berlin?

Yeah. I assume they would have happily clapped, maybe taken the words of the filmmakers to heart, and nothing would have happened if the lobbyist Volker Beck hadn’t scandalized it. Then the right wing press amplified his framing, and then many mainstream media outlets did the same thing without questioning whether what was said was in fact antisemitic. It’s hard to understand. When someone Jewish with expertise on antisemitism, like Prof. Meron Mendel, head of the Anne Frank Institute, says the Berlinale speakers were not antisemitic. When a non-Jewish ex-politician with an extremely colorful history, to put it kindly, says they were, the second voice becomes the official narrative. I really think this could have been a learning experience. But unfortunately, it seems none of the German media or politicians who defamed the Israeli filmmaker Yuval Abraham as an antisemite, thus endangering him and his family, have seen grounds for an apology. I hope so much that this might make German politicians reconsider attacking artists in the future – the fact that doing so not only puts their careers but their lives in grave danger.

Israel is a country with a right-wing extremist government which is at war. So, not a dissent-friendly climate! And yet the one Israeli media platform that called Abraham an antisemite withdrew the statement. In Germany, no-one has said they’re sorry, no-one has retracted their allegations. This should raise concerns about whether Israeli, Palestinian, and other foreign artists are going to want to come here in the future, or whether they will feel it is too dangerous.

My experience from talking to artists outside Germany is a sense of shock about the level of discussion here. More and more people are talking about the Strike Germany campaign. Do you as an organization have a position towards Strike Germany?

We don’t have an unified position on it. In general, we support every artist, every worker’s right to strike, it has always been an important tool of political pressure, and protest, and it will always be a tool that for artists – freelancers by definition – to use, means risking a lot. Whether there was an organized strike or not, there are increasing gestures of protest aimed at Germany, for instance the return of Goethe medals.

What do you think the balance forces in the art world is? It seems that the repression is increasing, but the reaction to the repression is also growing. Are we going in a positive or negative direction at the moment?

I don’t know, it’s really hard to say. This situation is extremely polarizing, a lot of beliefs are being tested, a lot of trust is damaged, and more and more international cultural workers are considering or planning to leave the country.

I think a lot of Israelis and Palestinians, Jews and Muslims are acutely aware that they are serving as a projection surface, and that they are being portrayed as monolithic homogenous groups in a relationship of enmity. And that this serves political interests that are not their own, and this portrayal makes life harder and more dangerous for members of all of these groups.

Do you see a special role for international artists?

Choosing a career in art generally means prioritizing freedom over security, perhaps this makes artists more likely to voice their convictions publicly. International artists, like all migrants, bring different perspectives into a national discourse, different histories, cultural values, experiences of otherness. Reading media in other languages, from other countries than the place one lives in, means noticing when a national discourse or consensus starts to shift away from international standards. So many migrants, whether they work in the arts or not, tend to notice this is happening now here. For example, recently a journalist criticizing foreign artists in Germany on a publicly funded radio station stated that “Germans are the new Jews”. A pretty shocking and shockingly inaccurate opinion, but unfortunately indicative of extremist tendencies taking hold within the German media mainstream. Paying attention when foreigners living here say that they are troubled by what is happening could help Germany to avoid increasing international isolation.

Where do you see the Arts in Germany or Berlin going now?

I think we’re at a very dangerous tipping point. Legislation is being proposed on many levels that is purported to protect Jewish life in Germany, but that could also be easily used to suppress critical voices, say, resistance against fascist movements within Germany. This was another concern regarding the clause, how it set a precedent for governmental interference into freedom of speech that could easily be misused for very different purposes down the line. The election prognoses are terrifying. How Germany as a country and how the German government decides to move forward in terms of respecting freedom of speech and freedom of expression is crucial to protecting democracy in Germany.