The backstory

In late September, I joined the great migration to Kassel to experience the city’s international art festival, referred to as “documenta” (this year named documenta 15). According to its website the origin of the event dates back to 1955, when the Kassel painter and academy professor Arnold Bode endeavored to bring Germany back into dialogue with the rest of the world after the end of World War II, and to connect the international art scene through a “presentation of twentieth century art.”

Presently, documenta is an exhibition of contemporary art held in Kassel every five years under changing Artistic Direction. documenta is considered one of the most important exhibitions of contemporary art worldwide. Kassel’s “Museum of 100 Days,” as documenta is often called, has become a seismograph for international contemporary art and its engagement with current social issues attracts artists and visitors on a global scale. This year, the 15th documenta is being curated by the Jakarta-based artists’ collective ruangrupa. This year documenta exceeded initial projections, attracting 738K visitors who came to the mountainous city to take part in the monumental exhibits.

Unfortunately, documenta 15 fell victim to Germany’s controversial censorship, provoking unfounded claims of antisemitism. In reaction to these claims, ruangrupa collected 65 signatories and issued an assertive open letter addressed to documenta’s board and shareholders, including the city of Kassel and the German state of Hesse. This letter addresses the emotional sentiment exasperated by German institutions’ policing through manufactured censorship, “we are angry, we are sad, we are tired, we are united.”

Visiting documenta 15

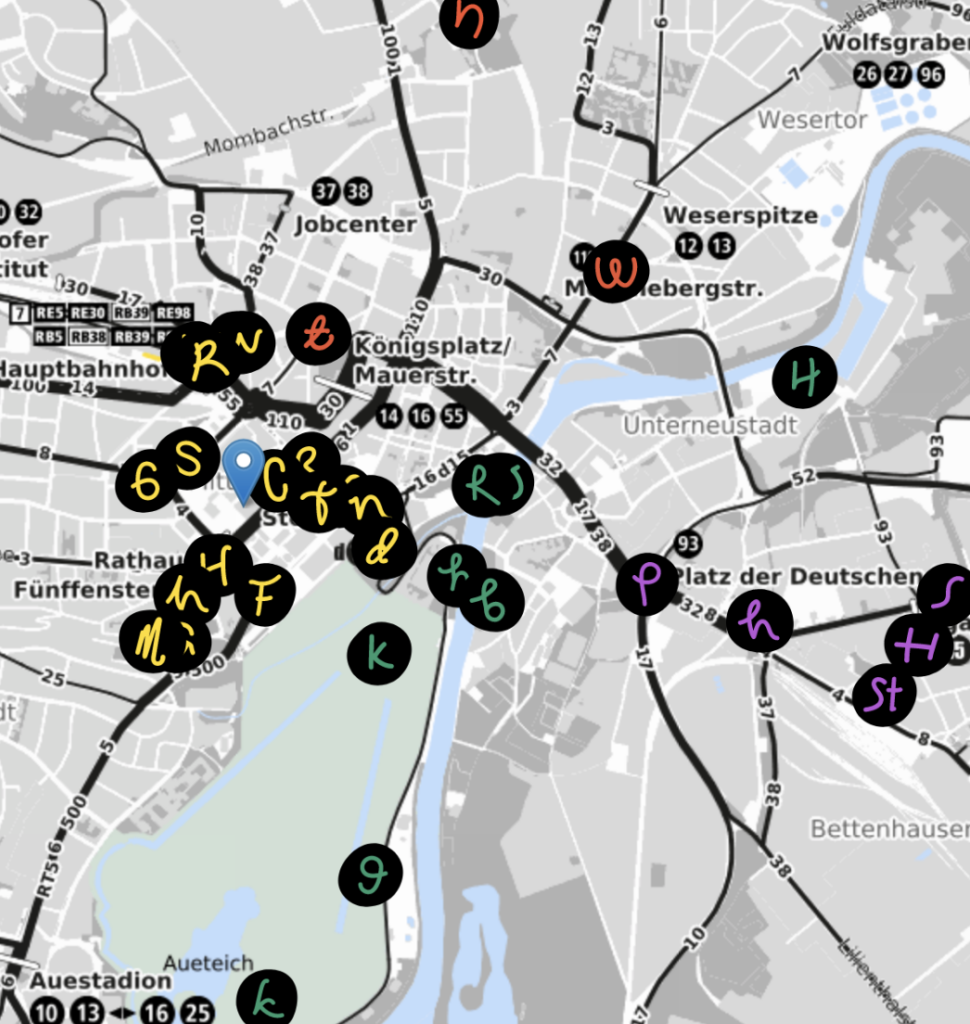

I spent two full days touring the endless exhibitions scattered around Kassel (as seen on the map below). documenta strives to offer compelling experiences for less privileged audiences. ruangrupa brought forward a whole generation of artists and types of practice for the 15th edition of Documenta delivering [a social] purpose, giving “some idea of what it is like to make art in precarious political, economic and social circumstances.”

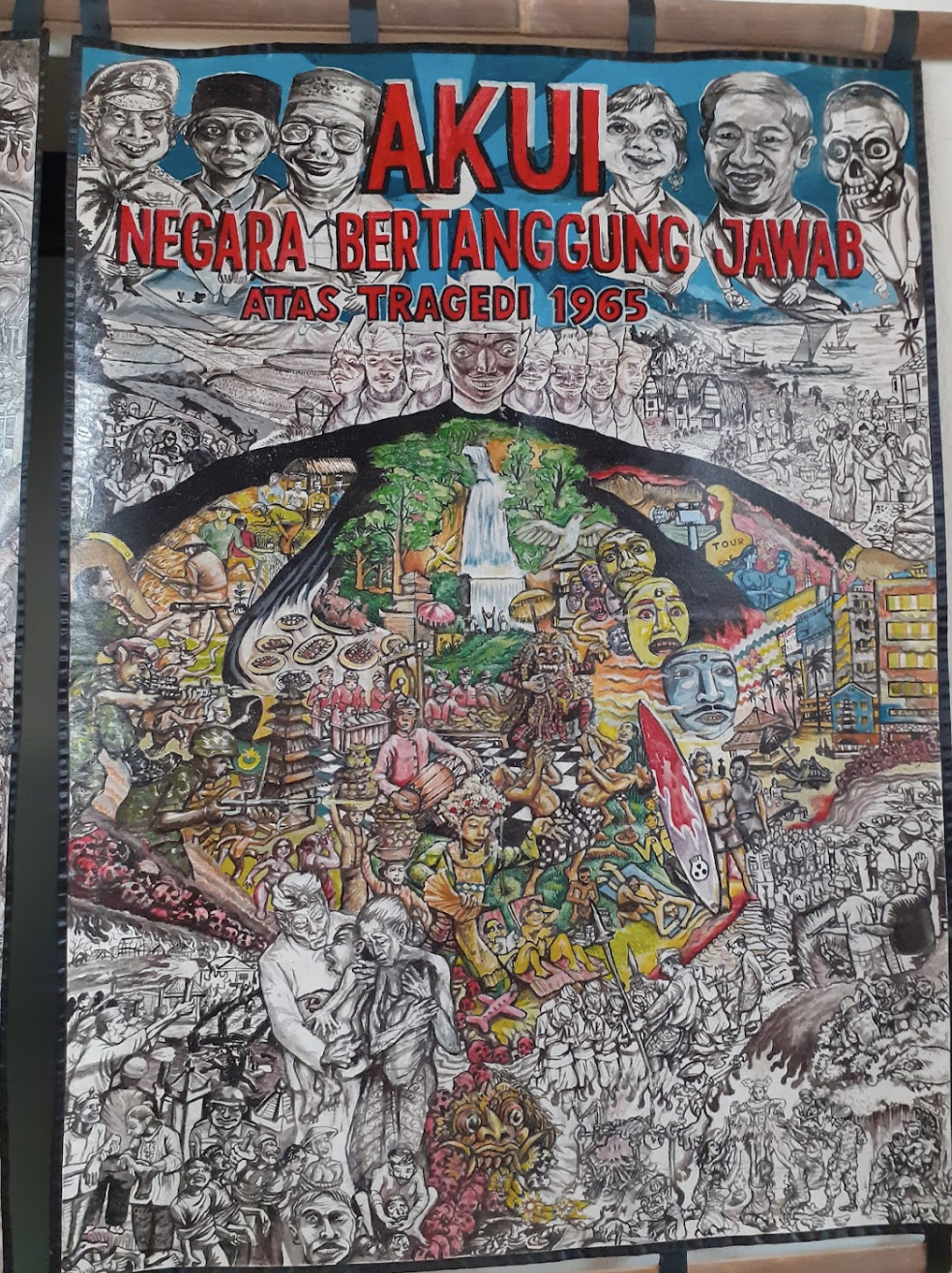

Taring Padi

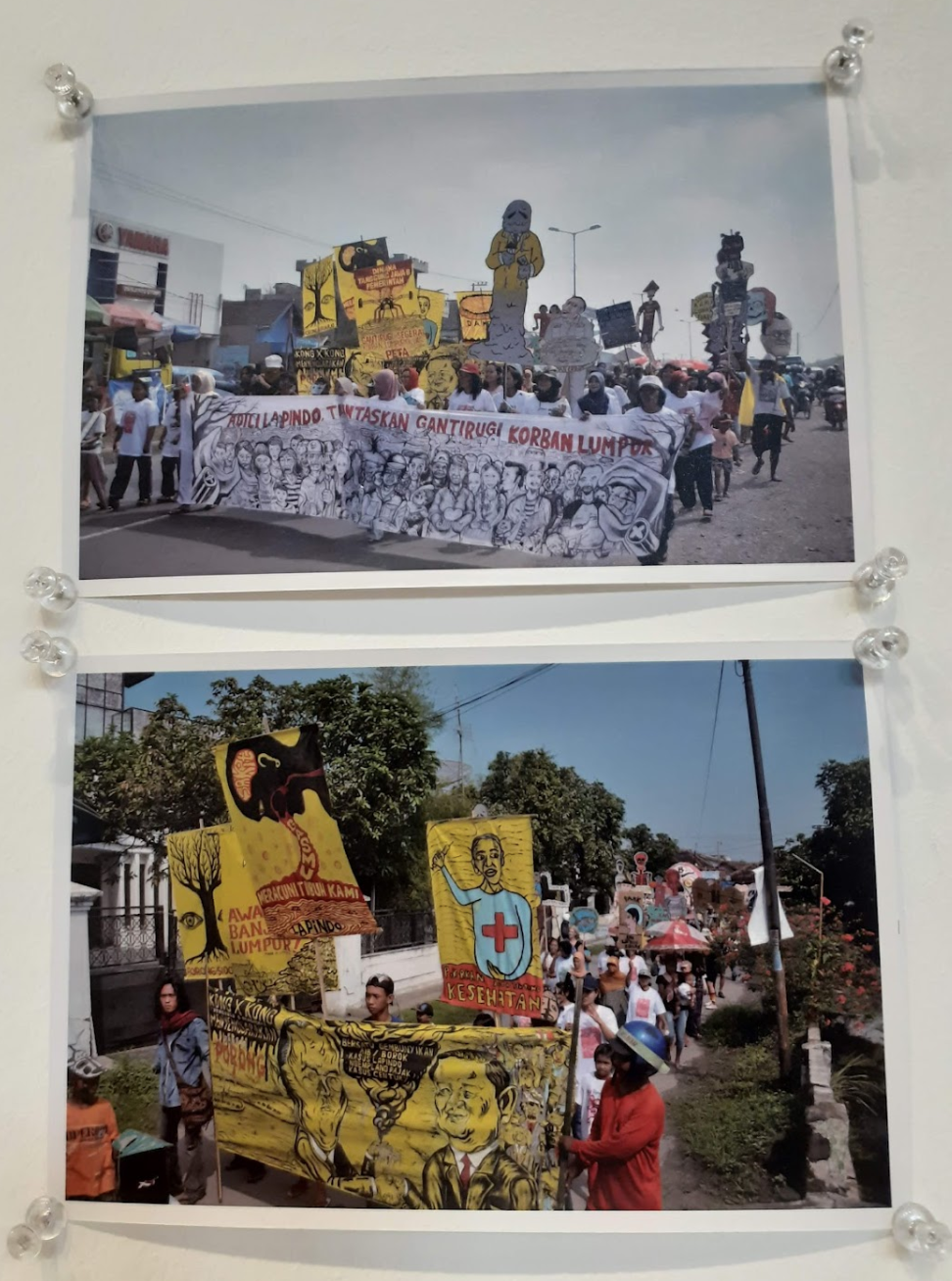

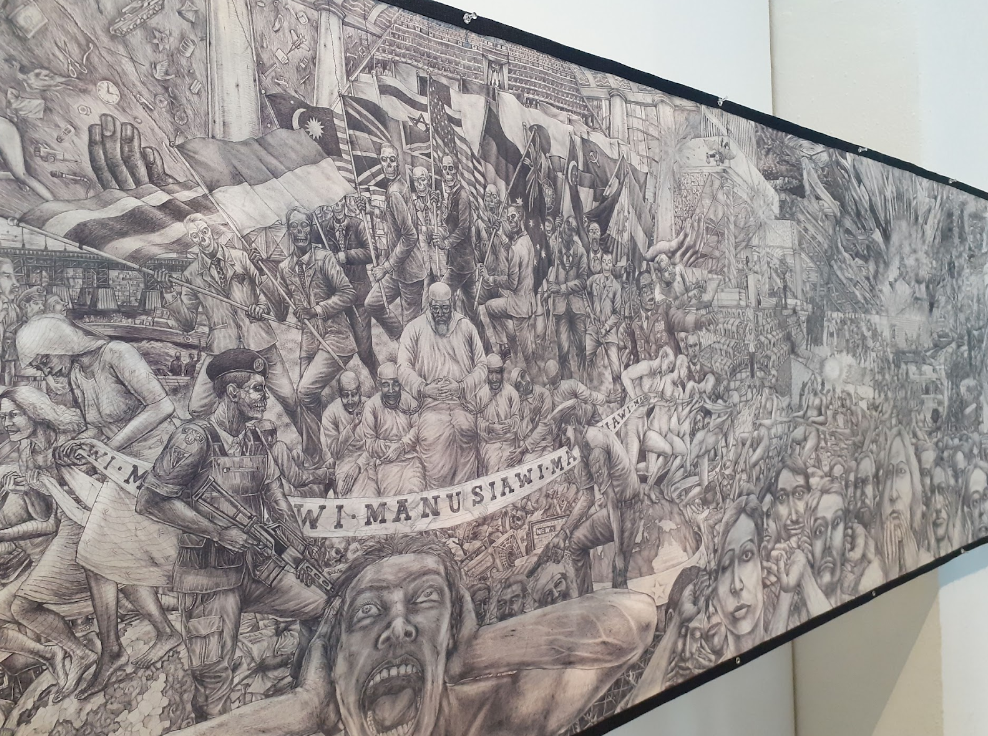

The Taring Padi dates back to 1998, founded by a group of progressive art students and activists in response to the Indonesian socio-political upheavals during the country’s reformation era. “In 2002 Taring Padi became a collective in order to further inclusivity and to facilitate personal dynamic of its members, whilst maintaining its progressive and militant character in realizing the potential of art as a tool for social change.” Over the years the group has produced a distinctive collection of banners, woodcut posters, and wayang kardus (life-sized cardboard puppets) which have produced examples for art as a tool for social change within socio-political and cultural solidarity and action. Taring Padi’s murals and painted works are colorful, using an array of vibrant—sometimes intentionally garish or, evidently, unintentionally offensive—symbols and figures.

Regrettably, several pieces that were planned for display became “confronted with harsh, outlandish accusations of anti-Semitism.” In an interesting element of the backlash against their now-removed mural People’s Justice (2002), their stated mission in documenta 15 is to communicate, as they write: “Flame of Solidarity: First they came for them, then they came for us”—a quote that, clanging against a furor about anti-Semitism evokes Martin Niemöller’s oft-referenced poem about the Holocaust:

“First they came for the Socialists, and I did not speak out—Because I was not a Socialist. Then they came for the Trade Unionists, and I did not speak out—Because I was not a Trade Unionist. Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out—Because I was not a Jew. Then they came for me—and there was no one left to speak for me.”

Smashing Monuments

The film “Smashing Monuments” by Argentinian Sebastián Diaz Morales, interviews five ruangrupa members who surprisingly emerge from the group’s anonymity. Each artist visits a different monument from the 1960s to early 1970s and engages in friendly mocking dialogue with the figures from a time of nationalism and power struggles juxtaposed with Indonesia’s past and present. The dialogue with these monuments sculpted with intentional meaning, provokes a thought-provoking dialogue “questioning and appropriating reality” which “strip reality of its familiarity and distort it, making it seem like something else.”

Tokyo Reels Film Festival

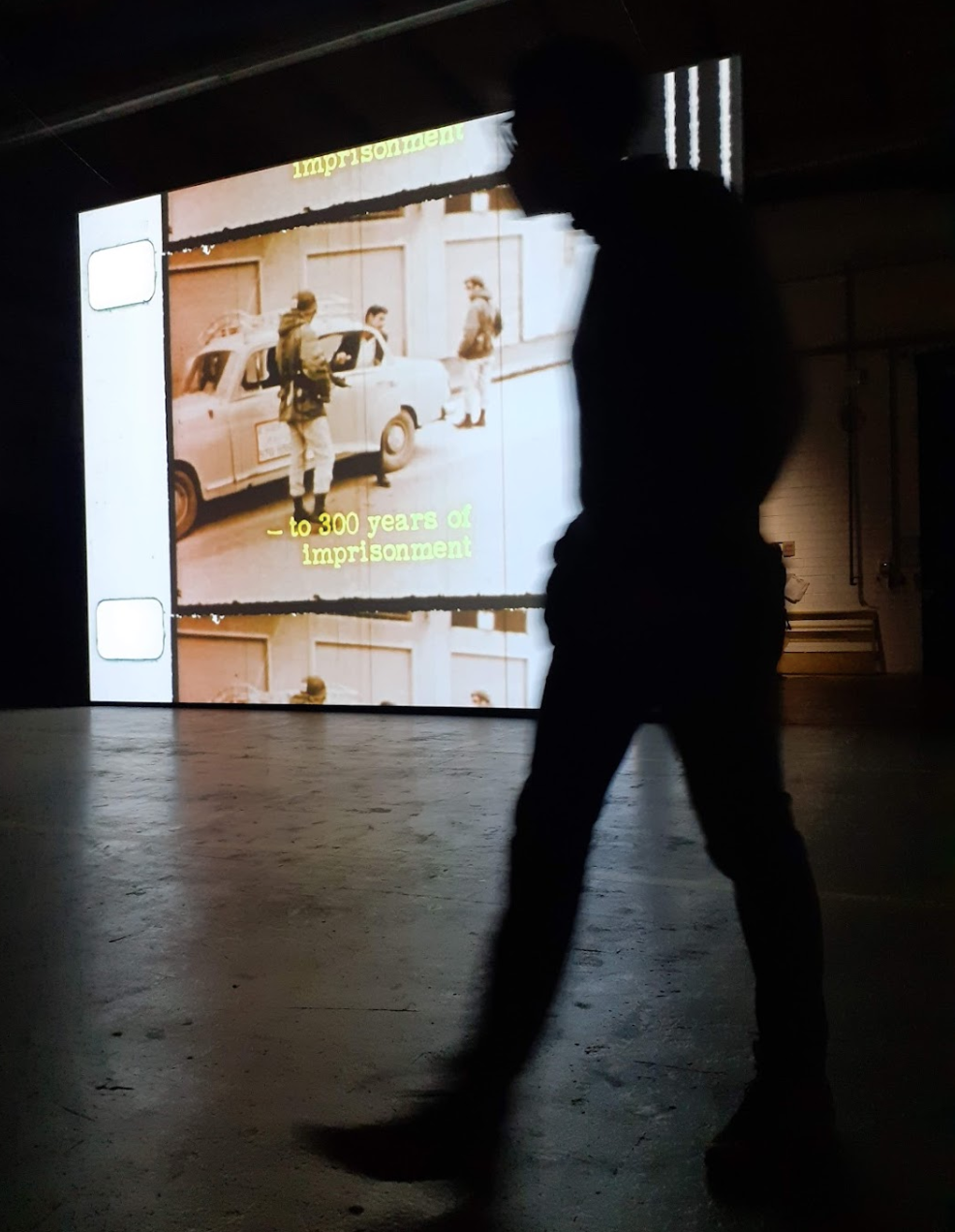

The Tokyo Reels Film Festival was presented by Subversive Film, a cinema research and production collective that aims to cast new light upon historic works related to Palestine and the region, to engender support for film preservation, and to investigate archival practices. Their long-term and ongoing projects explore this cine-historic field including digitally reissuing previously overlooked films, curating rare film screening cycles, subtitling rediscovered films, producing publications, and devising other forms of interventions. Formed in 2011, Subversive Film is based between Ramallah and Brussels.

documenta details that the screening of a recently restored film, sheds light on the overlooked and still undocumented anti-imperialist solidarity between Japan and Palestine. Subversive Film was entrusted with a collection of 16mm films and U-matic tapes, dozens of posters, and a full library safe-guarded by a Japanese solidarity group in Tokyo. The material, considered either lost or unknown to the public, was sent to Japan in several waves from 1967 to 1982.

Unsurprisingly, the Palestinian film was put on blast. As Dafoe writes “calling it “highly problematic,” the panel said the film is “filled with anti-Semitic and anti-Zionist set pieces” that are presented as objective fact. The artists’ “uncritical discussion” glorifies the “terrorism of the source material,” the committee argued.”

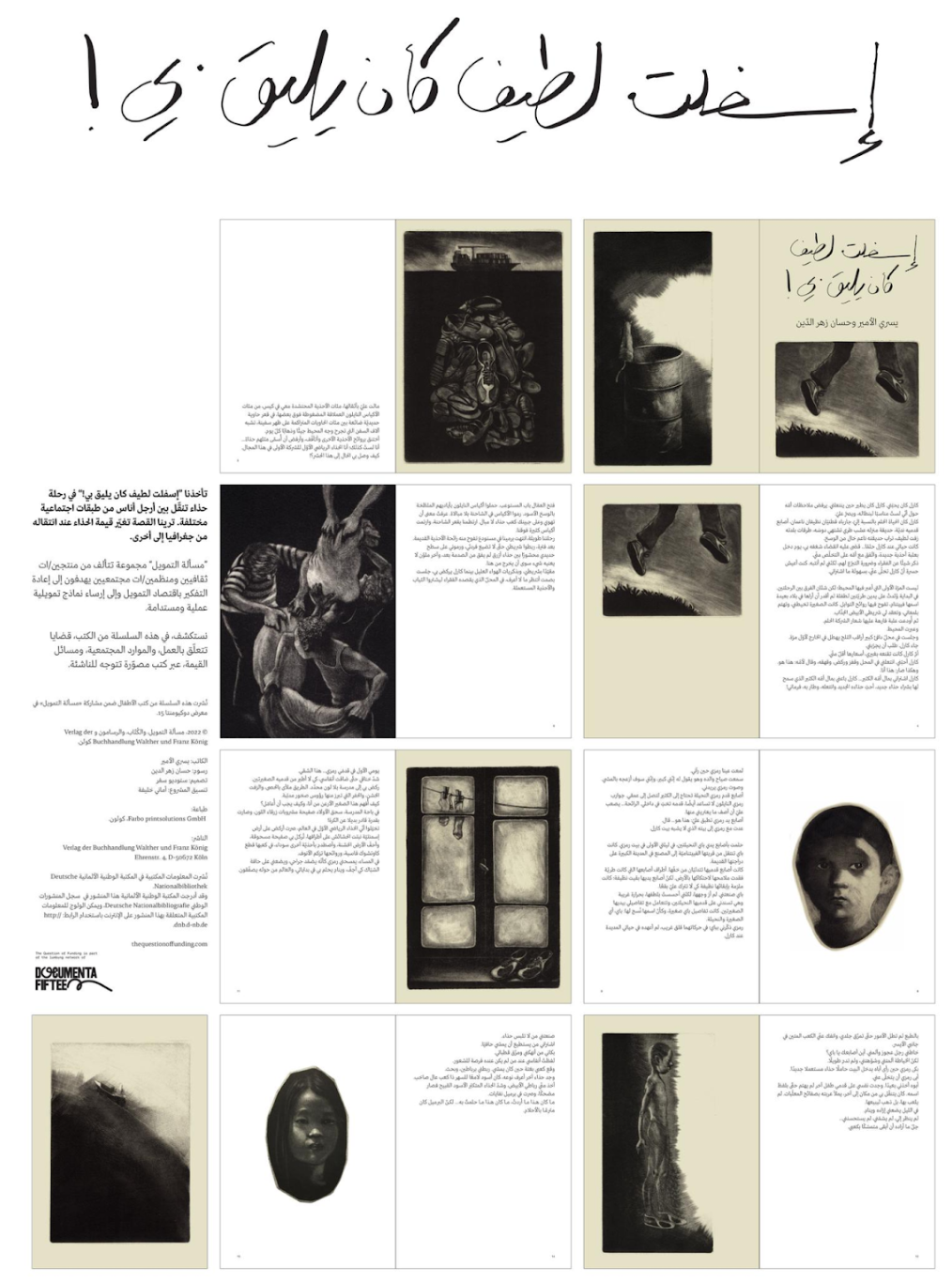

The Question of Funding

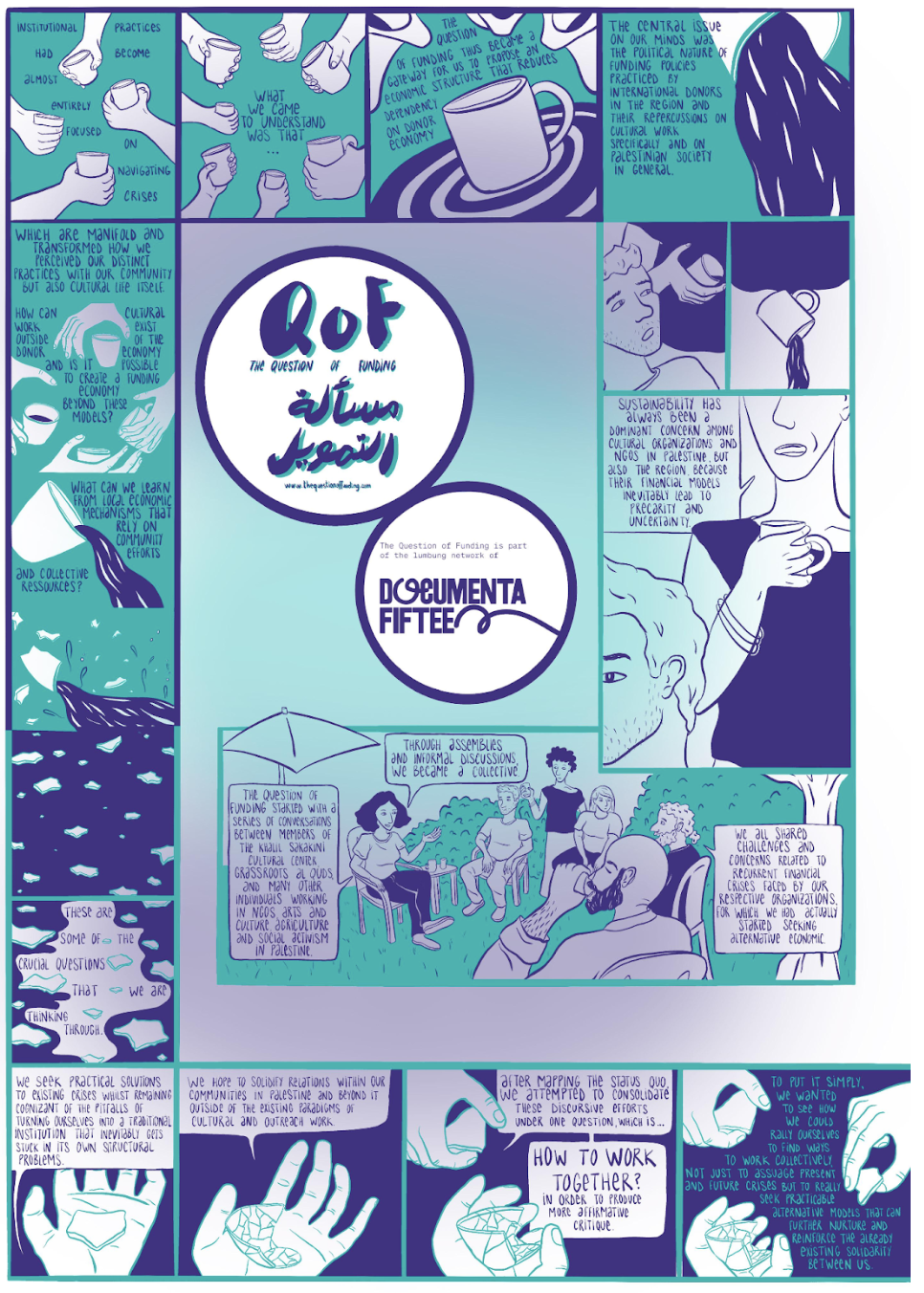

An exhibit offered by a growing collective of cultural producers and community organizers from Palestine called The Question of Funding focused on representing the ongoing process involved in producing, documenting, accumulating, and disseminating resources, experience, and knowledge with their wider community. It aims to rethink the economy of funding and how it affects cultural production both in Palestine and the world.

Born out of informal and open encounters within Palestine’s wider arts community, The Question of Funding sought to question, debate, and find solutions to the prevalent constrictive international funding models on which Palestinian cultural institutions continue to depend.* These encounters grew beyond the cultural sphere to include the wider Palestinian community. They touched on pressing issues concerning the political and economic roles of cultural work, both within and outside the institution, and their impact on cultural infrastructures in Palestine and worldwide.

In addition to the detailed infographics (displayed above), the exhibition offers a creative approach to the questions about the financial burdens of cultural work and the economy more generally will take the form of four books in which they explore issues related to labor, communal resources, and value through illustrated stories addressed to the youth. Each story was translated and offered in Arabic, German and English to promote accessibility.

The Gentle Asphalt I Deserved is the journey of a shoe that travels between different owners and classes. The story explores how the shoe’s value changes from one geography to the next.

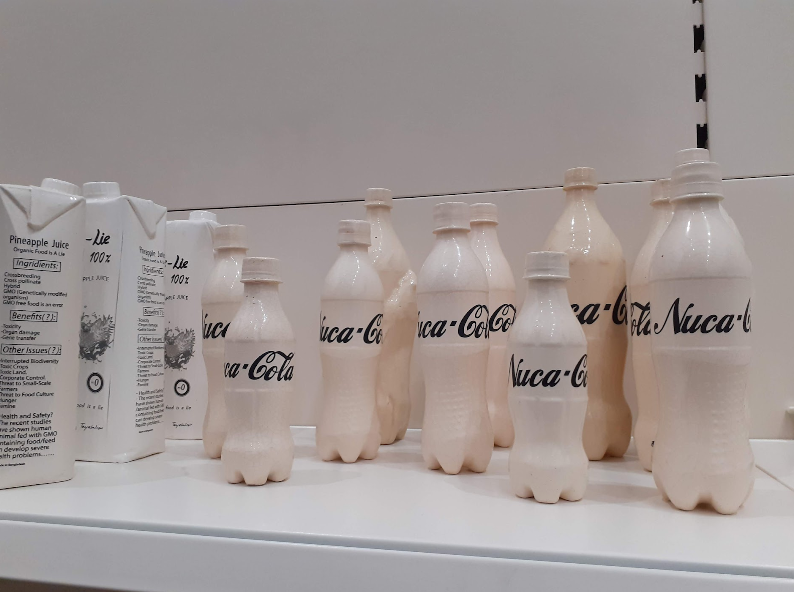

Britto Arts Trust: rasad

The rasad exhibit offers an elaborate twist on a visit to the market. A playful series of fake food objects—eggs, milk, vegetables, potatoes—is installed across a number of different shelves and inside a constructed pantry. These faux foods, made from surprising materials—including ceramic, plaster, plastic, cotton, and corrugated metal—include painted ceramic papaya juice cartons and squishy, embroidered cushions shaped like Campbell’s soup cans. Some, like painted cartons that remind viewers that “organic food is a lie,” are overtly political, drawing a thought-provoking connection between the international food trade, the legacy of colonialism, the slave trade, and ongoing economics of extraction and exploitation.

documenta’s Dismal Labor Conditions

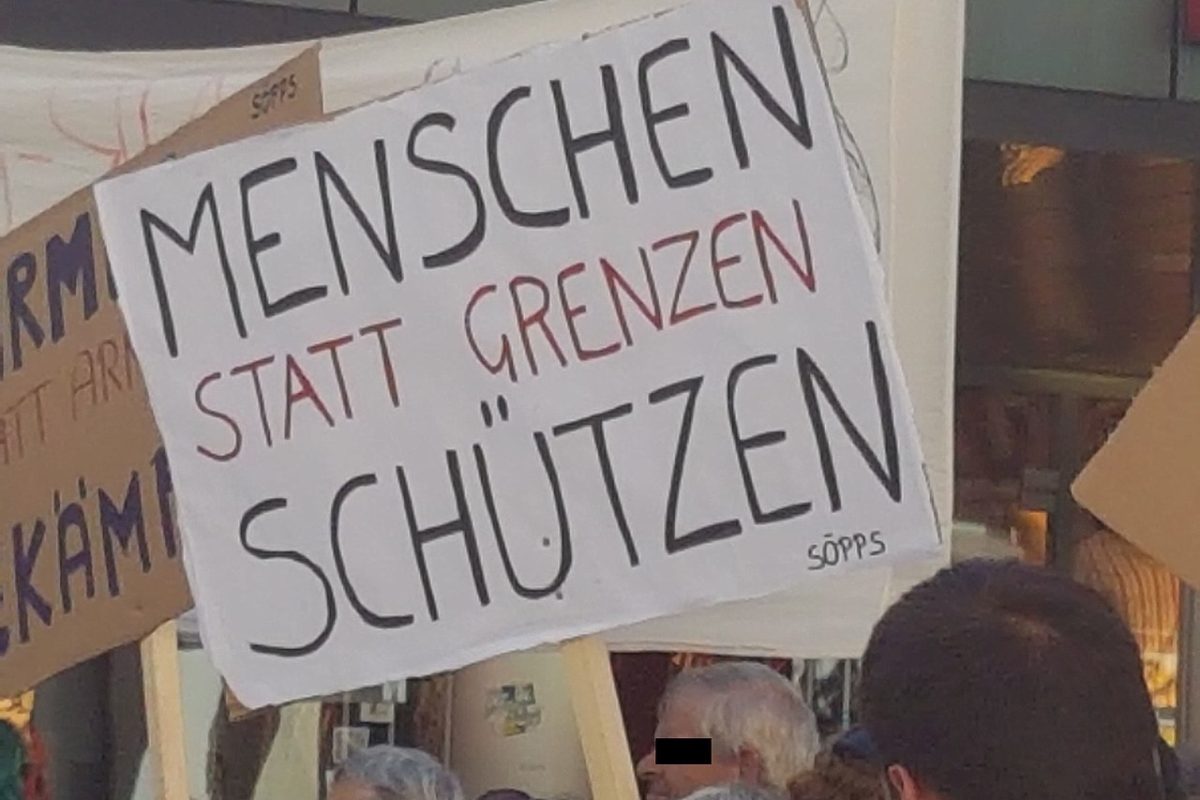

documenta’s last edition (documenta 14) made headlines regarding the “personal and political interests” that “led to lack of oversight ” and, allegedly, “borderline-illegal money transports”. Leading to bags of cash being transferred, and yet staff that earned well under the promised 9 euros/hour. Although the event happens every 5 years, there is plenty of time to see what else could go wrong. The ongoing anti-Semitism publicity and demonstrations became the focus, and this anger evolved into misdirected racist activity aimed at the staff themselves. “On May 28, the exhibition and living spaces of documenta were broken into and defaced with what can only be interpreted as a death threat.”

Gaining little attention were the continued poor labor conditions cast upon the staff of documenta. This open letter addressed to all members of documenta und Museum Fridericianum GmbH, outlines concerns from the employees regarding their intense working conditions, high levels of stress and the devaluation of their role – feedback that was given, but completely ignored. The letter goes on to detail dozens of examples of mismanagement including: poor staff coverage during covid outbreaks, violent communication from top-down staff members and uncompensated workloads, to name a few.

Overworked employees cast doubt over the documenta’s touted “lumbung spirit”. documenta employees provided context to their frustration:

“1,500+ artists have been invited to show work, requiring lots of extra red tape, from last-minute visas to readjusted wall labels.”

Unsurprisingly, the open letter mentions the problems are “rooted more broadly within the structures of culture work in Germany and beyond.” Here’s hoping documenta will finally turn a corner and start practicing what they preach in the godliness of their prestigious art platform for which they are internationally known.