Editor’s note: the interviewee’s identity has been withheld for their protection.

Could you tell me about your experiences of antisemitism at UdK?

My main experience of antisemitism in my workplace has been that of being ignored because I don’t fit into prescribed ideas of how a Jewish person should feel on the topic of Israel’s genocidal war. These ideas are projected onto me mostly by non-Jewish Germans, and it has led to my marginalization from conversations that are purported to protect my “safety.” In reality, these conversations shut down freedom of speech and particularly criminalize Palestinian, Middle Eastern, and Arab voices.

I’ve never encountered anti-Jewish hatred at protests against Israel’s genocide. If anything, I’ve felt welcomed on the basis of a shared cause. The violence I’ve seen has come from the police attacking Jewish protesters.

Earlier this year, a group of UdK staff, including the president, issued a statement claiming Jewish, Israeli, and “antisemitism-critical people” are being discriminated against. Have you observed this?

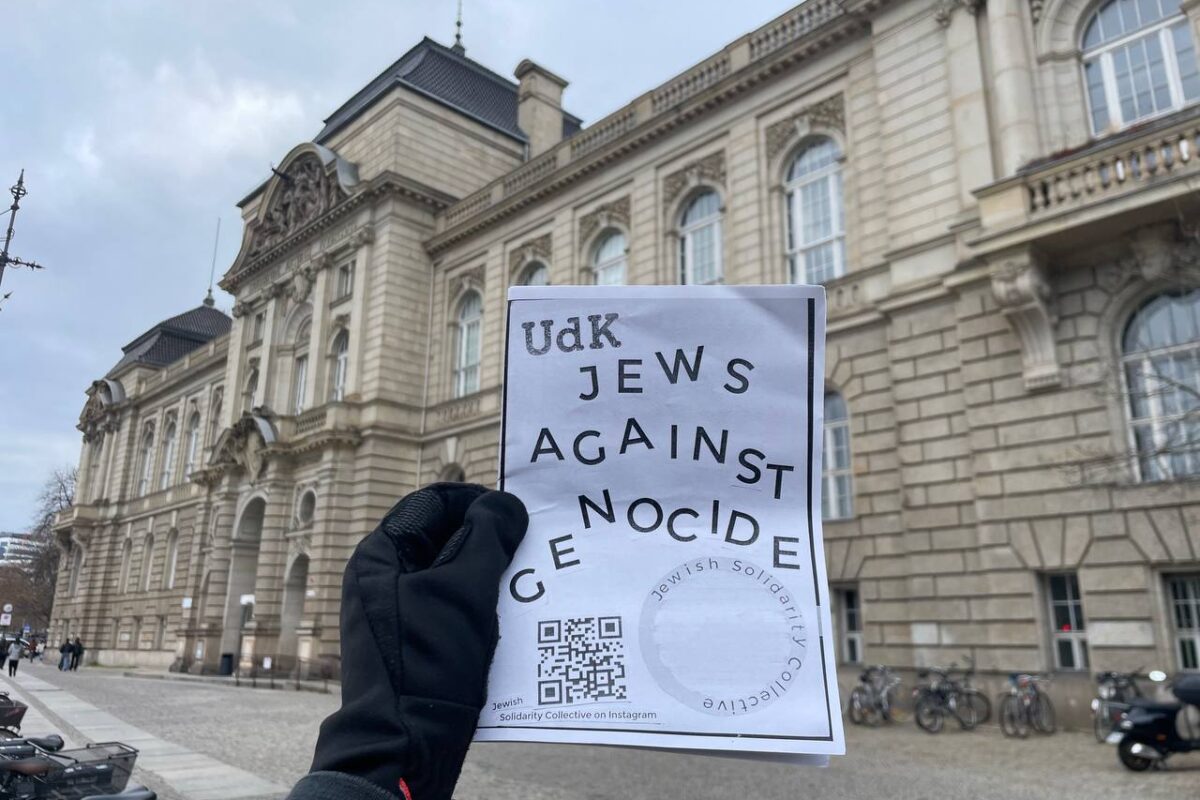

I haven’t heard concrete examples of antisemitic discrimination at the UdK. One example offered in the statement concerns a vigil in November 2023, which my group, the Jewish Solidarity Collective, believes was unjustly labeled as antisemitic. We argue that these inflammatory allegations of antisemitism shut down the possibility of more nuanced discussions about protest methods and political symbols.

I’ve also attended a meeting of Jewish members of the UdK. The most concrete example expressed there was discomfort over seeing students wearing the Keffiyeh as a symbol of Palestinian solidarity. Other Jewish people put on their Keffiyeh when they left the meeting — this simple difference already shows there are a range of positions within the Jewish community at UdK.

There’s been an image circulating of graffiti in a UdK bathroom that allegedly reads, “Free Jews from being,” Reportedly, the word “instrumentalised” was removed, and with that additional word the strange formulation would make more sense. The image is now being circulated as “proof” of rampant antisemitism. It’s become quite a neurotic and fear-driven environment with little space for careful and critical thinking, nor for listening to the diverse perspectives of Jewish people, let alone Palestinian and other Middle Eastern voices.

It does seem like the term “antisemitism-critical people” means that any non-Jew who supports Israel can declare themself to be a victim of antisemitism—even if their views are criticized by a Jewish person.

It does indeed seem that many of the loudest voices on antisemitism at UdK are non-Jewish. This interview in Die Zeit features four people discussing the issue, only one of whom is Jewish (and also Israeli), all of whom support the same narrative. There are a small handful of people who talk so aggressively about antisemitism at UdK, like Elias Braun, that it’s surprising to learn they aren’t Jewish.

You are part of a Jewish Solidarity Collective at UdK, which has demanded a meeting with the UdK President. Have you had a chance to speak with him?

The president of UdK took almost a month to respond to our request for a meeting. In the end he refused, suggesting we come individually or in pairs to his regular office hours for students, ignoring the fact that we are a mix of students and staff. He explicitly stated he would not regard those who came to his office as representatives of a collective. Despite our respectful attempts to engage with him, he criticized our anonymity and refused to meet with us as a group, claiming we were creating paranoia and mistrust in the school. As Jewish students and staff members who speak up against war crimes, the breaking of international law and ethno-nationalist ideology, we feel ignored and sidelined. It seems the presidium offers support only to Jewish students with whom they agree, while their experiences and opinions are framed as those of (all) Jewish students at the university.

The media continues to focus on a protest from last year, where some students had their hands painted red. How do you respond to claims that the protest was antisemitic?

I wasn’t at the protest, but other members of the Jewish Solidarity Collective were. The red hands were meant to imply complicity in violence, not an antisemitic gesture. This symbol is used in many international protest movements, including in Israel. From the reports of Jewish students who were there, the vigil was a mournful and emotionally charged shared experience which highlighted the deaths of children in Gaza; their names were read one by one. Jewish people were not targeted in any way — rather, the gathering became more heated when the UdK president was put on the spot by some protesters about the university’s public statement of solidarity with Israel.

Tania Elstermeyer, who claimed the red hands were antisemitic in the press, had previously been part of organization meetings for the vigil, having had the opportunity to raise concerns there about possible other readings of this symbol if she wanted to. Elstermeyer was thereafter also briefly hired as the interim (non-Jewish) Antisemitism officer at UdK. She collected names and filmed students engaged in pro-Palestinian actions at the Rundgang exhibition, including at least one Jewish student, and was removed from this position after a freedom of information request revealed what she had been up to.

A Jewish person with right-wing views has claimed that Jewish students at UdK have faced antisemitism. In this interview, it sounds like many of the people facing “discrimination” might actually be just non-Jewish, “antideutsch” supporters of Israel.

There is a lack of differentiation between discrimination and being confronted with opinions which might make one uncomfortable. I believe the confusion between these experiences is how non-Jewish Germans can come to feel that they can be a victim of antisemitism. Discomfort may be subjectively felt as a ‘‘threat’’ but that does not mean that the expression of differing political opinions constitutes discrimination or harassment. Ironically, it is exactly this room for dispute and debate that the university is supposed to offer. Even the author of the IHRA definition of antisemitism, Kenneth Sternm emphasizes this distinction, especially on campuses.

I’m frustrated that the full diversity of Jewish students’ voices aren’t heard in these discussions, that anti–zionism is equated with antisemitism, and that non-Jewish Germans so often speak over Jewish people while claiming to speak for us.