On June 9th, 2024 President Emmanuel Macron decided to dissolve the French Parliament. He has overseen three months of an hitherto unseen political saga marked, inter alia, by the unprecedented speed at which progressive political forces joined together to build a widely supported program, and by the resignation of the current Prime Minister Gabriel Attal after an unexpected victory of the Nouveau Front Populaire (New Popular Front).

One can question the intentions of the President of the Republic at the time of the dissolution, however, the return of this grenade to its sender places him places him face to face with a challenge and forces him to honour his democratic obligations. After promising to appoint a new Prime Minister by mid-August, Emmanuel Macron is obviously failing to adhere to the rules of the institutional game. Furthermore, the decision not to select Lucie Castets is a mistake in several respects.

First, parties from the left union have all compromised by proposing a candidate who is not affiliated with any party but who is committed to implementing “the entire program, nothing but the program”. Jean-Luc Mélenchon, leader of La France Insoumise – a political formation much detested across the political spectrum – even announced that he was willing not to appoint any ministers from his party. This strong commitment was quickly dismissed by the President of the Republic. This willingness from the left to offer concessions was supposed to leave Emmanuel Macron no argument for refusing to appoint Lucie Castets. That was his first mistake from a symbolic perspective.

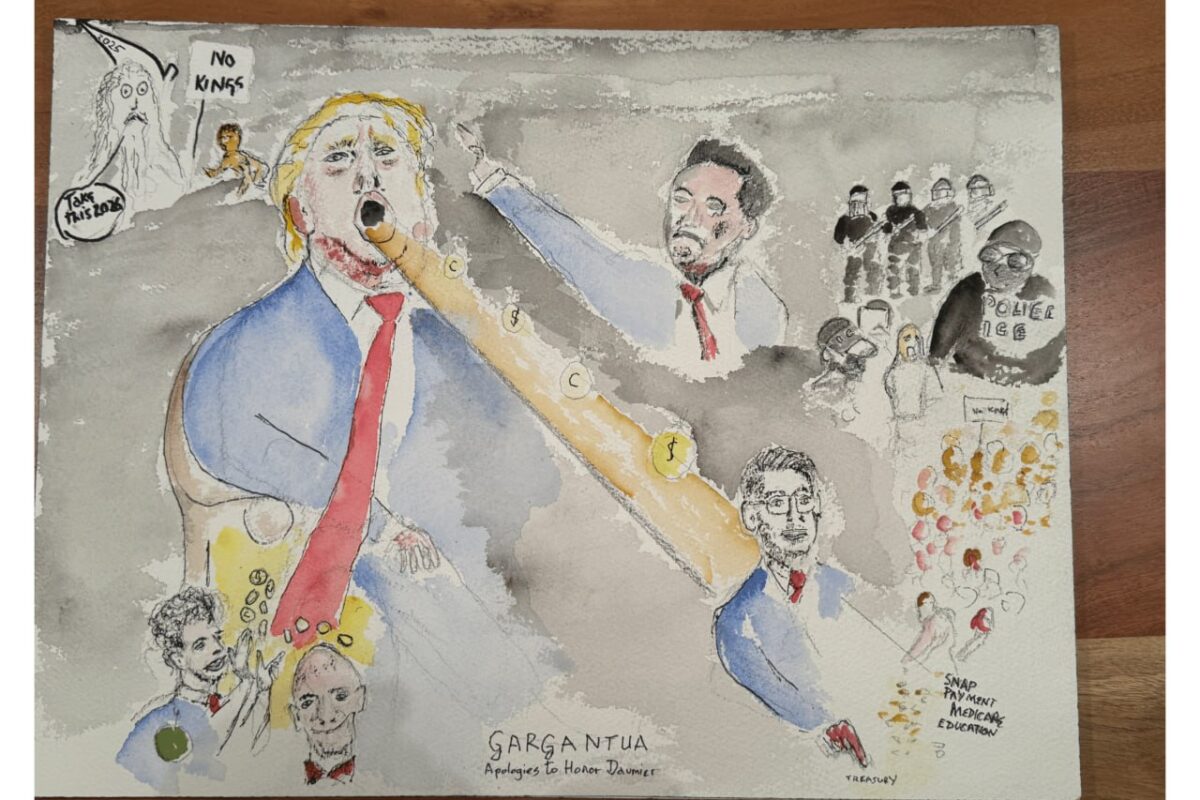

Lucie Castets, the finance advisor at Paris City Hall and co-founder of the collective “Nos services publics” (Our Public Services), embodies a broadly consensual ambition within the left and within a large part of the French population. Indeed, the latest reforms conducted during Macron’s term, on the pretext of bringing public accounts back in order, are symptomatic of a policy that pretends to ignore the real causes of economic difficulties. He remains deaf to the claims from a trampled France: that of the Yellow Vests, of the rural districts, of the socioeconomically disadvantaged areas where police violence persists, and more broadly, of all those who suffer from increasing inequalities in a country where unemployed people and care professionals are being denigrated and devalued. By proposing the founder of a collective aimed at improving the quality and access to public services as Prime Minister, the NFP promised to send a strong signal to the French people, who are aware that many essential services such as education and the healthcare are facing a crisis. Emmanuel Macron is therefore also committing a political mistake.

One of the arguments raised by the presidential minority is that appointing Lucie Castets would generate institutional instability, as she would immediately face a vote of no confidence from the right and from the parties affiliated with the presidential camp. However, this potential outcome is not uncommon in parliamentary regimes, nor under the Fourth, or even under the Fifth French Republic. Indeed, the likelihood of cohabitation used to be high at the time when legislative elections regularly took place two years after the presidential elections. A Prime Minister from a relative majority obviously risks being censured. Yet not only is this risk predictable and is part of parliamentary normality, but it is also lesser compared to the risk of institutional blockage: handing over the keys of the executive to a government team logically coming from the majority is key. Indeed, if a vote of no confidence prevents the formation of a lasting government, it at least has the merit of clarifying the political process and allows for running and even introducing social progress in public affairs, whereas inertia leaves no room for achievement. Inertia, that Emmanuel Macron is purposedly maintaining, helps him gain time while issuing decrees to keep ruling against the backdrop of an institutional turmoil, plunging the country into illiberalism.

Indeed that is the last and most critical democratic fault. The President, who is convinced of his legitimacy despite the results of the ballots last July, deliberately capitalises on the deficiencies of the French institutional apparatus. The bad faith with which he disparages the compromises and proposals of the victorious camp while exercising disproportionate power is symptomatic of a biased constitutional order, whose rules allow a super-powered leader to enact unpopular measures and to act against democratic common sense. As Lucie Castets herself summarized during an interview on France Inter last month: “[The President] wants to be head of state, head of the government, and head of a party […] this is satisfactory for nobody.”

Demonstration: Lucie Castets Prime Minister. Defend Our Democracy. Saturday, 7th September, French Embassy. Called by La France Insoumise, Berlin