Mary Wollstonecraft, author of The Vindication of the Rights of Women, is often referred to as the “Mother of Feminism”. Her life was both short, eventful, and controversial. She died a painful death, aged only 38, from post-natal complications, shortly after the birth of her second daughter, Mary. This left her newly married husband, William Godwin, himself a well-known leading radical, to bring up three-year-old Fanny, Wollstonecraft’s daughter from a previous relationship, and the baby Mary, who later became famous as the author of Frankenstein.

Wollstonecraft was born on a farm somewhere between London and Epping Forest. She grew up, the second of six children, on farms in Epping Forest, Wales and Yorkshire, with an alcoholic father and a mother whom Mary tried to protect from the father’s abuse. Her early education came from six years at Day Schools whilst the family was in Yorkshire, and from growing up on different farms and playing sports with her brothers.

One of the people who stimulated Mary, “a wild, but animated and aspiring girl of sixteen”, to develop her writing skills was Frances Blood, who lived in Newington Butts, whom she had met during one of the family’s stays in London. According to Godwin’s Memoirs of Mary Wollstonecraft, “Fanny undertook to be her instructor” and after meeting Fanny “..…a connection more memorable originated about this time, between Mary and a person of her own sex, for whom she contracted a friendship so fervent, as for years to have constituted the ruling passion of her mind”.

Wollstonecraft decided at the age of 16 to become independent and earn her own living. She started out on the traditional route for middle-class women at the time, by becoming a companion to a Mrs. Dawn in Bath but left the position to go home to care for her mother until her death. Wollstonecraft then moved to Waltham Green in Fulham to be closer to Fanny. The two of them then set up a Day School, first in Islington, then in Newington Green, along with Mary’s two sisters. The school became unviable when Wollstonecraft followed Fanny to Portugal to support her through an illness.

Sadly, Fanny died in childbirth, leaving Mary bereft of the close friend she loved, admired and learned so much from. Ten years later, in a subsequent publication, Letters from Sweden, Norway and Denmark, Wollstonecraft wrote: “I cannot without a thrill of delight, recollect views I have seen, which are not to be forgotten, nor looks I have felt in every nerve, which I shall never more meet. The grave has closed over a dear friend, the friend of my youth; still she is present with me, and I hear her soft voice warbling as I stray over the heath.”

In Islington, in an environment of radical thinkers, Wollstonecraft got to know the Radical preacher Dr. Richard Price, a fervent supporter of both the American and French revolutions. Wollstonecraft became a writer, critic and intellectual, self-taught and through the support and influence of the radical circles she was introduced to by the publisher Joseph Johnson. She mixed with Thomas Paine, best known for his Rights of Man and whose pamphlet Common Sense influenced the American revolution; Joseph Priestley, chemist and radical; the poet and artist William Blake, who illustrated her Stories from Real Life (an education manual for children commissioned by Joseph Johnson) as well as William Godwin and the Swiss painter, Henry Fuseli. William Roscoe, from Liverpool and a supporter of the abolition of slavery, commissioned the less well-known and atypical portrait of Wollstonecraft (possibly by John Williamson) in which she is depicted dressed and posing in the style of a French intellectual (See the head of this article).

During her life in France in 1792, Wollstonecraft became friends with leaders of the French Revolution as well as a group of international writers and artists. She dedicated A Vindication of the Rights of Women to Talleyrand, one of the early leaders in the French Revolution. She had an unwavering belief in God and in the power of Reason and Science to bring about positive social change and improvements. Her stint as governess to the two daughters of Lord and Lady Roxborough in Ireland taught her to abhor the ways of the aristocracy in general, particularly those of aristocratic women, who appeared to prefer their fawning dogs to their own children.

The French Revolution in particular had a profound impact on Wollstonecraft. When Edmund Burke attacked the French Revolution in his Reflections on the French Revolution, Wollstonecraft wrote a reply A Vindication of the Rights of Men published in 1790 by Joseph Johnson. This was a precursor to her famous work A Vindication of the Rights of Women, also published by Johnson in 1792. This makes Wollstonecraft, as Miriam Kramnick puts it, “not so much the inheritor of a feminist tradition as she is the writer of its manifesto”.

Wollstonecraft develops a wide range of arguments in A Vindication of the Rights of Women, but her central argument is that women should be educated equally alongside men in order that they could develop the power of reason throughout their lives. She was not a revolutionary intent on overthrowing English society or the family, although she railed against, poverty, inequality and the role of property.

Rather, Wollstonecraft wanted to see a transformation in men and women, with women to be treated as fully independent human beings and not be brought up to be the sexual playthings of men. Marriage should be based on friendship and autonomy, not on the subordination of women to men. She loathed the hypocrisy attached to the concept of “the fallen woman”, opposed asylums and Magdalens (institutions set up to contain women who got pregnant outside of marriage or who worked as prostitutes) and believed no woman should have to give herself to a man she did not love and desire. She opposed licentiousness in men, arguing for real sexual passion informed by respect.

Her arguments are directed at middle-class women, and men, where she believed change might most easily be wrought, with education playing a key role. She advocated a system of co-education based on developing physical strength as well as the mind and stimulating a spirit of enquiry. Children should play outside and not be subject to physical punishment. Women should be educated to be economically independent, to be physicians as well as nurses, and to take up other occupations. Training in human anatomy and medicine would help women to better care for their families. Wollstonecraft’s vision of female beauty was based on women developing their physical strength, in contrast to the vision of the simpering, weak and pale sex-object cultivated in her day.

Two years after A Vindication of the Rights of Women, Wollstonecraft wrote An Historical and Moral View of the Origin and Progress of the French Revolution in part based on her own personal observations. Wollstonecraft had in fact ‘fled’ to France to try to break her attraction to the Swiss painter Henry Fuseli, whose wife turned down a proposal for a ‘ménage à trois’.

In Paris, Wollstonecraft met and fell in love with an American, Gilbert Imlay. They lived happily in Neuilly for several months and Imlay was the father to Wollstonecraft’s first daughter — named Fanny in recognition of her lost friend. Wollstonecraft got a certificate from the American authorities identifying her as Mrs Imlay in order to gain protection after the decision of the National Convention in 1793 to expel all British subjects. However, Wollstonecraft was never actually married to Imlay.

The relationship became unworkable when Imlay headed off on business trips that included embarking on other relationships. Her letters to Imlay make painful reading as she wrestled with attempting to break the relationship with the man she was passionately in love with, the father of her daughter, but who she ultimately discovered, was living with someone else. One day she was full of resolve to break with him entirely, the next she was desperately trying to get them back together again, to the extent of proposing that she, Imlay and his lover all live under the same roof.

The experience of attempting to maintain this relationship, twice brought her to the brink of suicide. The first time, Imlay rescued her after she attempted overdosing on laudanum. The second time, she jumped from Putney Bridge but was pulled unconscious from the Thames by fishermen. In the end she succeeded in making the necessary break with Imlay to build a life for herself and her daughter.

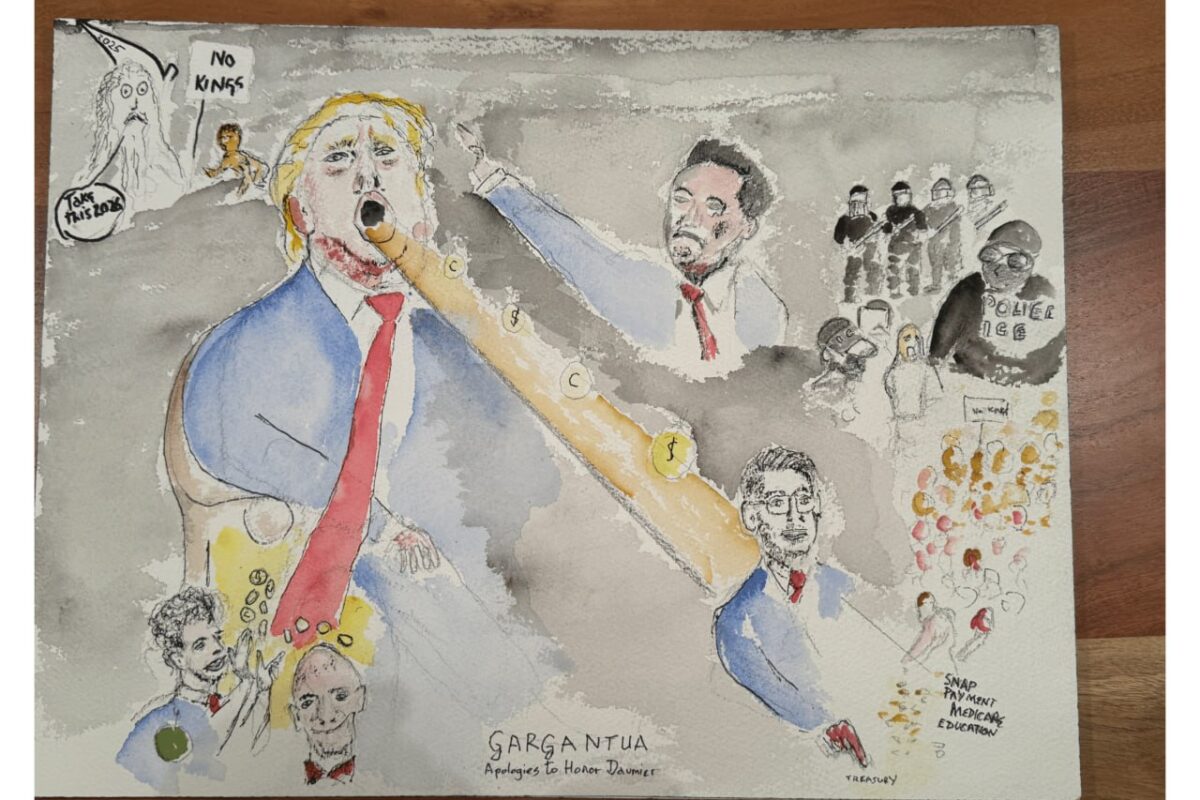

Wollstonecraft was appalled by the extent of the bloodshed during the reign of Terror in the French Revolution. Nevertheless, she argued that perhaps it was necessary to rid society of all the evils of oppression. An Historical and Moral View of the Origin and Progress of the French Revolution is interesting for several reasons. She was concerned “to trace the springs and secret mechanism, which have put in motion a revolution, the most important that has been recorded in the annals of man.”

She captures the oppression of the peasantry, having to bear the parasitic burden of 60,000 of the nobility, a 100,000 strong standing army, 200,000 clergy who took 25 per cent of the produce of France, 60,000 monks and 50,000 tax collectors. She saw the revolution as a movement of the people: “who were slaves and dwarfs, bursting their shackles and rising in stature, suddenly appeared with the dignity and pretensions of human beings.”

It was the people, who by successive approximations, assessed the moves by the forces round the King, Louis XVI, to draw in the European powers to support the restoration of feudalism. And it was the masses, men, women and children who organised the defences in Paris, mingled with the standing army, won soldiers to their side and who played the decisive role in the capture of the Bastille, that symbol of reaction whose cannons had been turned on revolutionary Paris.

In May 1795, Wollstonecraft, undertook a trip to Scandinavia with her baby Fanny. She was hoping to resolve some business problems for Imlay and thus help repair the breach in their relationship. She wrote regular letters to an imaginary lover (presumably Imlay), later published as Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway and Denmark. Godwin, who had not been impressed on his initial meetings with Wollstonecraft, wrote “If ever there was a book calculated to make a man in love with its author, this appears to me the book.” The Letters made a deep impression on the Romantic poets.

Although not widely read, The Letters, are among the best of Wollstonecraft’s writings. She describes vividly the countryside she travelled through, as well as the walks and rides she took. Her love and appreciation of the beauty of the scenery is everywhere combined with down-to-earth details such as the stench from the use of herring as fertiliser in Denmark. She gives succinct résumés of the way of life of different communities, noting differences in wealth and poverty.

About Sweden she writes:

“In fact, the situation of servants in every respect, particularly that of the women, shows how far the Swedes are from having a just conception of rational equality. They are not termed slaves; yet a man may strike a man with impunity because he pays him wages, though these wages are so low that necessity must teach them to pilfer, whilst servility renders them false and boorish. Still the men stand up for the dignity of man by oppressing women. The most menial, and even laborious offices, are therefore left to these poor drudges. Much of this I have seen.”

Her observations of the economic and political structures of Sweden, Norway and Denmark led her to conclude that the small farms that underpinned the economy of Norway meant that it was the freest community with the mildest of laws. “The distribution of property into small farms produces a degree of equality which I have seldom seen elsewhere; and the rich being all merchants, who are obliged to divide their fortune amongst their children, the boys always receiving twice as much as the girls, property has a chance of accumulating till overgrowing wealth destroys the balance of liberty.”

Along the way there are personal reflections on commerce and greed, revised opinions about the superior level of culture of the French compared with those who lived in northern climes, her love for her daughter Fanny and the delight she took in her presence, alongside her fears for the kind of world Fanny would face when she grew up:

“You know that, as a female, I am particularly attached to her; I feel more than a mother’s fondness and anxiety when I reflect on the dependent and oppressed state of her sex. I dread lest she should be forced to sacrifice her heart to her principles, or principles to her heart. With trembling hand, I shall cultivate sensibility and cherish delicacy of sentiment, lest, whilst I lend fresh blushes to the rose, I sharpen the thorns that will wound the breast I would fain guard; I dread to unfold her mind, lest it should render her unfit for the world she is to inhabit. Hapless woman! What a fate is thine!”

An intrepid and imposing traveller, Wollstonecraft was able to persuade captains of ships to do her bidding, from putting her ashore where she wished, to rescuing travellers on a French boat in distress.

A short time after her return to London, Wollstonecraft embarked on a romantic relationship with William Godwin, a partnership that brought them both great pleasure. Society was becoming increasingly conservative during a reactionary backlash against the French Revolution and the repression unleashed against the Radical reformers by Pitt’s government. Miriam Kramnick writes:

“….. Pitt’s repression was irresistible. The Treasonable Practices Act broadened the definition of treason, the Seditious Meetings Act made it illegal to gather for a lecture without a law officer present, and in 1798, Habeas Corpus was suspended.”

So Godwin and Wollstonecraft married when Wollstonecraft became pregnant in order to ensure that she would not be cut out of their social circles. Since both agreed that two people in a relationship should remain autonomous, instead of the woman becoming one person with the man, they set up house together, but Godwin retained a flat several doors down in Somers Town where he would often spend the day on his own work. They enjoyed trips out as a family, with Godwin developing a close relationship with little Fanny, but allowed themselves the right to enjoy mixed company on their own.

Wollstonecraft’s standing as a writer and public figure has undergone many changes. After William Godwin’s biography revealed that she had not been married when her first daughter was born, her social reputation was seriously tarnished, whilst her reputation as a Radical was increasingly a disadvantage, associated as she was with the Jacobin leadership of the French Revolution, the likes of Robespierre and Terror.

She was remembered by the followers of Robert Owen and writers such as George Elliot and Elizabeth Barrett Browning but disowned by the Suffragettes. In the early twentieth century, the American anarchist Emma Goldman saw Wollstonecraft as “a pioneer of modern womanhood”. In 1959, the Fawcett Society laid a wreath at Wollstonecraft’s grave and leading feminists Kate Millett and Germaine Greer both hailed The Vindication as an important work.

More recently, Wollstonecraft’s relationship with Fanny Blood has been seen as an example of ‘the love that cannot speak its name.’ Wollstonecraft’s novel Mary, A Fiction “has been claimed by lesbian literary history” and her portrait by John Williamson has been included in the LGBT – Pride and Prejudice Project in the Museum of Liverpool. Unaccountably, most of the original correspondence between Fanny Blood and Wollstonecraft has disappeared.

Wollstonecraft wrote two novels, Mary, A Fiction, written in 1788, and the unfinished Maria or The Wrongs of Women published posthumously in 1798. Mary, A Fiction is a complex novel of two relationships, one between two women, Ann and Mary, the other between the same woman, Mary, and a man, Henry. Mary had been married off to a man she loathed so both relationships with Fanny and Henry transgressed contemporary social norms. The novel reflects Wollstonecraft’s own relationship and love and friendship for Fanny Blood and, perhaps too, a bisexuality in her desire for a relationship with the painter Henry Fuseli, and possibly his wife too.

Maria or The Wrongs of Women explores the nature of contemporary marriage where women were treated as the property of their husbands. It centres on the life of a woman trapped in a marriage she is unable to escape, whose husband’s sole interest is in her potential wealth and has her committed to an asylum when she attempts to escape his control. The novel also highlights the fate of the poorest women in society, through depicting a woman born as an illegitimate child, who is treated as an outcast and only survives through a combination of backbreaking work as a servant, washerwoman, prostitution and stealing.

Ashley Tauchert, in an essay about the two novels says:

“I will read Wollstonecraft’s Fiction for modalities of female-embodied same-sex desire expressed through figures of disavowal. I will argue that what this Fiction offers is a female-embodied character whose desire is encoded as masculine. Following Teresa de Lauretis I suggest that this masculine encoding is, in turn, one of the disavowed signs of female-embodied same-sex desire.”

It is impossible in this short article to capture fully the unique qualities of this extraordinary critic, philosopher, writer, sparkling conversationalist and fearless radical thinker, but I hope I have conveyed something of her singularity and ignited an interest in her work. Wollstonecraft was a trenchant critic of the society of her day and the conditions of women’s lives.

She showed the way oppression shaped women’s lives in different classes in the eighteenth century. In her own life choices, she transgressed the boundaries of sexual mores and gender roles. She has rightly become a feminist and lesbian icon, and the depth and range of her analysis and vision are still relevant for those of us fighting women’s oppression today.

Further Reading

- Ferguson, Susan, 1999, “The Radical Ideas of Mary Wollstonecraft”, Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue Canadienne de Science Politique 32, (no 3) 1999: 427-450.

- Godwin, William, 1798, Memoirs of the Author of the Vindication of the Rights of Women.

- Tauchert, Ashley, 2000, Escaping Discussion: Liminality and the Female-Embodied Couple in Mary Wollstonecraft, Erudit

- Tomaselli, Sylvia, 2021, Wollstonecraft – Philosophy, Passion and Politics, Princeton University Press.

- National Museums Liverpool, The allure of Mary Wollstonecraft