Rewatching Studio Isao Takahata’s Pom Poko on its 30th anniversary leaves behind a nostalgia idiosyncratic to 90’s Japanese animation. It shares a political and philosophical narrative seen in many Ghibli productions. Pom Poko takes us back to the 1960s, during a period of rapid urban expansion to tell a story about nature’s native populations and their struggle against capitalism and land theft, with the Tanuki (racoons) serving as political subjects resisting the consequences of consolidated industrialisation.

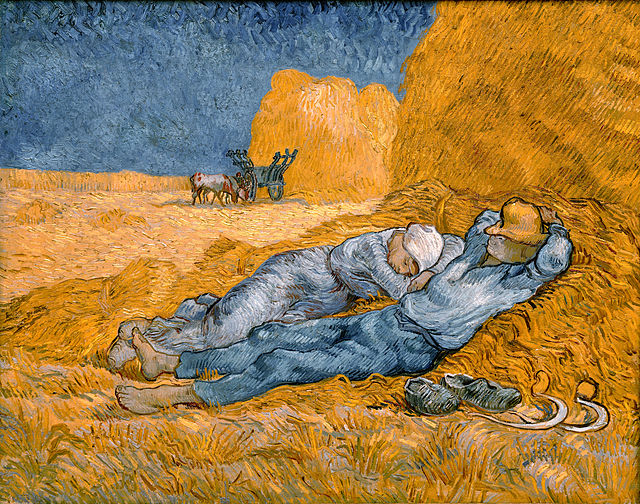

The Tanuki live in the Tama Hills on the outskirts of Tokyo. The Hills are threatened urban sprawl. The Tanuki’s habitat and homes are being destroyed to make way for construction, causing resource scarcity and forcing them to venture into the city where they scavenge in the trash and around fast-food outlets. The Tanuki possess magical abilities that allow them to shapeshift into objects, people, animals and mystical creatures. Rooted in Japanese folklore, this magical realism plays a central role in depicting the deep connection between the natural and supernatural, creating a world in which animals can tap into hidden knowledge normally out of reach for urbanised humans (a recurring theme in Ghibli films). Using this magic, the Tanuki fight back through a series of campaigns involving direct action, peaceful protests, human sabotage and shape-shifting performance. Their societay is deeply communal, one in which elders hold leadership while younger Tanuki possess the drive and initiative needed to turn theory into practice and stop the construction-site development in their forest.

It’s no coincidence that, six years after Pom Poko, Paul Crutzen globalised the idea of the ‘Anthropocene’, identifying a new geological epoch marked by human-driven intervention on Earth’s geological strata. While the idea had circulated in scientific circles before, it wasn’t until 2000 that Crutzen’s framing of human activity as a potentially hazardous force gained widespread recognition. Understanding this requires analysis of the production relationships that serve as primers for the emergence of the Anthropocene. Global industrialization not only spurred urban expansionism but also defined an international working class. So, what does this have to do with Pom Poko and how can we use Marx’s theory of alienation to understand the struggles posed by the Tanuki which frame humans against nature?

As Dan Swain points out, in the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts Marx opens a conversation on the relationship between humans and nature and humans and labour. In his words, ‘our alienation from the products of labour means that we also become alienated from the natural world in which we live and work’. The bulldozing of Tama Hills represents the disconnect between the worker’s environment and the rest of the ecosystem, including all other species (such as the Tanuki). This tension pushes the workers to identify with a faceless construction company instead of allying with the Tanuki; an alliance that would not only free them of their alienation from nature but would also allow them to demand better working conditions and ultimately, self-emancipation, just like the Tanuki aspire to.

The workers live on-site, with their boss promising meager pay raises as a means to keep them working through precarious conditions. During the post-war period rural populations had little choice but to migrate to cities in search of employment. This led to an influx of rural labour in urban centres, a trend driven by land reforms and mechanisation of agriculture. Many country farmers and labourers were pushed off their land, just like the Tanuki. There is an imperative to point out the similarities in both as exploited subjects—the material conditions leading to the exploitation of nature and the exploitation of workers are rooted in the same production relations.

Another shared aspect which Marx wrote regarding alienation in nature has to do with the industrial process of soil erosion, described by Dan Swain as, ‘eroding soil by extracting nutrients from it which were never replaced but rather dumped as waste in the cities’. This exact issue is shown in Pom Poko when a different community of Tanuki who live in another section of Tokyo’s urban sprawl reach out for help. Their suffering is caused by soil and debris from the construction site in Tama Hills being dumped directly onto their territory, destroying their home and displacing them. Marx notes that, ‘Capitalist production…causes the growing population to achieve an ever-growing preponderance…it disturbs the metabolic interaction between man and the Earth, i.e., it prevents the return to the soil of its constitutive elements…All progress in capitalist production is a progress in the art of, not only of robbing the worker, but of robbing the soil.” As a result, both human and non-human populations find themselves at the mercy of capitalist production.

The Tanuki communities unite to resist this land dispossession by holding a series of conferences and general assemblies. In preparation, they summon Tanuki shape-shifting masters from nearby islands to teach them advanced transformation techniques. During the debates, tensions arise as differences in ideology lead to a split. Gonta, a fierce and militant Tanuki, takes on a leadership role within a small faction of tanuki who advocate for direct action and the killing of humans. This group, frustrated by the limitations of peaceful protests and negotiations, believes that the only way to reclaim their land is through lethal tactics, even at the expense of their own lives. Gonta’s splinter group isolates from the main Tanuki community, who prefer the shape-shifting approaches. Lacking the majority’s support, this Gonta and his group launch a desperate, kamikaze charge in a dramatic, last-ditch confrontation with riot police at the edge of the city. Tragically, the mission proves fruitless. The bodies of Gonta’s comrades pile up, killed by police forces. His strength spent, Gonta is run over by a truck in the middle of the city. The isolating nature of physical confrontation without a real force correlation (that is, the support of the whole Tanuki community) leads to failure. No matter how committed Gonta and his comrades were to the cause, they needed the rest of the Tanuki to succeed.

It’s worth mentioning the role of ‘Inugami Gyobu’, a fox from Tama Hills who also possesses shape-shifting abilities (in accordance with Japanese folklore). Along with a small cohort of other foxes, he has adapted to human society, learning to blend in and thrive by leveraging human systems rather than opposing them. He embodies the danger of social movements being co-opted, assimilated, or ‘bought out’ by capitalism. In proposing a plan to the Tanuki, he tries to convince them to abandon their cause and finally blend in with the humans adopting a shape-shifting form forever. His acceptance of defeat implies that resistance is futile. By choosing self-preservation over resistance, he sends a message to the Tanuki that adapting to urban life and abandoning their existence is the only viable option. His plan divides the Tanuki, creating another ideological split between those with the capacity to assimilate and those who would continue to resist (it is also imperative to mention, that like the foxes, not all Tanuki possess shape-shifting abilities, meaning some would be left behind to fend for themselves or, like the non-magical foxes, die out entirely).

When Marx identifies the breakdown in the relationship between humans and nature due to capitalist industrial modes of production, he suggests, ‘not returning to a lost country life but to abolish the distinction between town and country’. Marx’s perspective on nature is rooted not in mysticism but in practical concerns, particularly of human health, especially for the working class who, like the Tanuki, are suffering the consequences of urban pollution and highly concentrated human populations. He argues that to survive as human and non-human species, a total re-organisation of society is necessary, and requires ‘exerting conscious collective control over the relationships of production’. This is a relevant counter-argument to some environmentalist positions regarding individual behaviour or ‘reducing your carbon footprint’ as a potential solution. As Swain says, ‘One of the most popular solutions proposed for climate change is ‘‘carbon trading’’ whereby companies can continue to pollute on one side of the world in exchange for investing in renewable energy or planting trees on the other side. This could not be a clearer example of commodity fetishism, where even Co2 molecules are understood as commodities which can be traded off against one another’.

Pom Poko ends on a bittersweet note. After all their efforts to resist urban development fail, the Tanuki are ultimately forced to integrate into human society to survive. Many take on permanent human forms, blending into city life and adopting human jobs. A few tanuki manage to maintain a small foothold in the remaining green spaces, where they can still live freely, but these areas are scarce and shrinking, making them long for the world they lost, painfully aware of the displacement and loss of identity that urban expansion has imposed on them and becoming estranged from their own cultural practices and traditions, forced into roles that have no connection to their identity or heritage.

Nevertheless, despite the profound loss, the ending scene conveys another side of the story showing Tanuki who continue to live by their traditions, gathering food, playing, and carrying on their natural lives. Although most Tanuki have scattered, the ones who remain in small green spaces keep a communal spirit alive. They portray how solidarity and shared traditions are still possible beyond alienation. Through a Marxist lens, this communal existence is rooted in the belief that people could freely develop and express themselves if freed from capitalism and exploitation.

“For those of you who feel the same way as we do, those who feel lost and unsure in this new world, please remember, you can still find us, if you know where to look. We’ll be here, living as tanuki, in the last patches of green.”

-Shoukichi (Tama Hills Tanuki)