Last Sunday, Portugal headed to the polls for an early general election to the National Assembly, in which two thirds of the 10 million population came out to vote – the highest voter turnout rate in three decades.

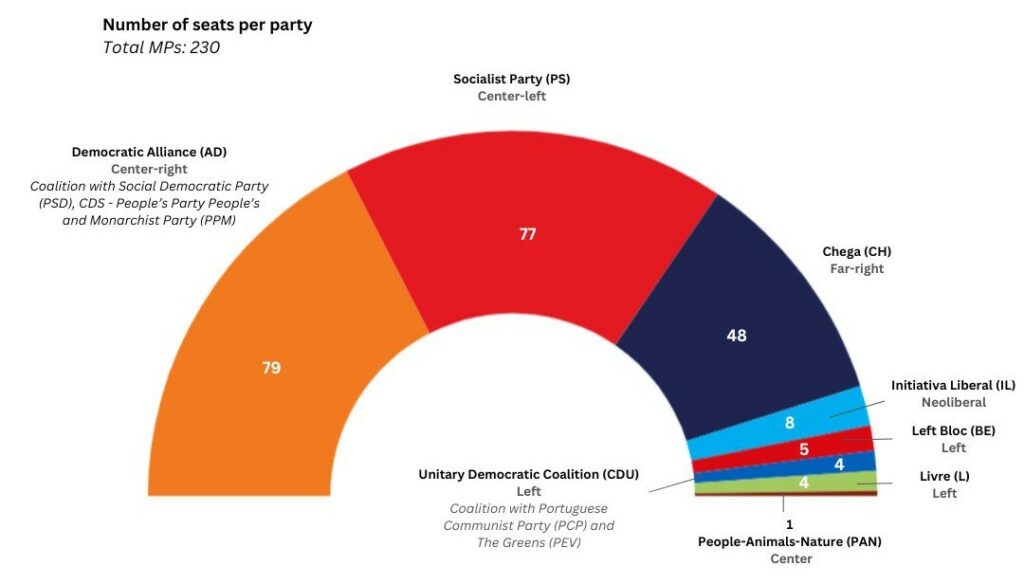

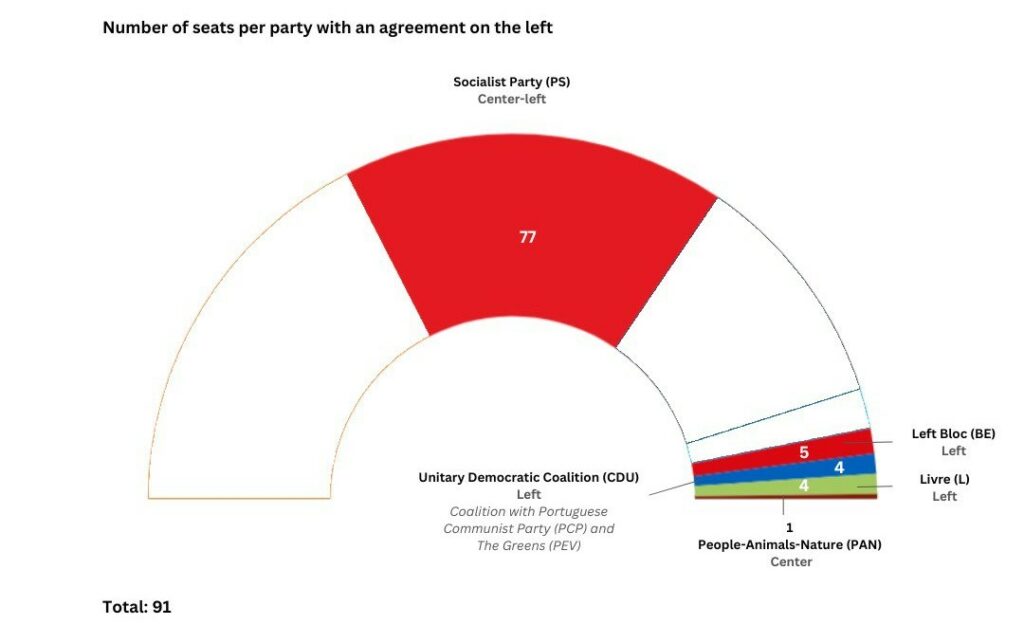

While the results mark the country’s shift to the right, there remains only a two seat difference between the two mainstream parties, who have alternated in power since the end of Salazar’s dictatorship, leaving some room for ambiguity about the future. The Democratic Alliance – a center-right coalition led by the liberal-conservative Social Democratic Party (PSD), with the support of the Christian democratic CDS – People’s Party – and the People’s Monarchist Party (PPM) obtained 79 seats. The Socialist Party (center-left), which has been in power for the last eight years, won 77 seats.

Even more concerning is the fact that, out of the 230 seats, the populist far-right party Chega (“Enough” – that defends things such as chemical castration of sexual offenders, or removing the nationality of naturalized citizens who commit crimes) secured 48 seats – almost as many as there have been years of Portuguese democracy – coming in third place and tripling their 2022 vote. Chega now holds immense negotiation power, with one in every ten electors choosing to side with them, marking yet another nail in Europe’s democratic coffin. Ironically, the rise of the far-right comes in the year that marks the 50th anniversary of the Carnation Revolution in Portugal, that overthrew the dictatorship the country lived through between 1933 and 1974, and started a revolutionary process in the years that followed, with the participation of the workers and popular masses.

How did we get here?

Between 2015 and 2019, Portugal was ruled under a political agreement established between the center-left Socialist Party (PS), the Left Bloc (BE) and the Portuguese Communist Party (PCP), a pact that became known as “Geringonça”, roughly translated to English as “contraption”. That pact succeeded in overthrowing the right from power. It forced PS to the left by pushing back on austerity measures imposed via the troika and the previous government, and by advancing social rights that inspired political leaders all over Europe.

The formal pact ended in the 2019 election, by the socialists’ ambitious strategy, that despite their efforts, did not achieve a parliamentary absolute majority, and had to keep negotiating and compromising to maintain the support of the left parties. However, the COVID-19 pandemic took a big toll on the Portuguese economy and the left partners’ support was conditioned on specific proposals and red lines. These were to guarantee sturdy measures in wage increases, improved labor laws and strengthening the National Health Service – measures that, despite their previous defense, the Socialist Party was now intransigent in including in the 2022 state budget, instead preferring to be closer to the Portuguese right – and therefore provoking new elections.

Prime minister and PS leader António Costa successfully achieved his absolute majority in the 2022 campaign, by blaming the left-wing parties for the political crisis (resulting in the Left Bloc and the Communist Party losing some of their seats), and seducing the Portuguese historical moderate-center electorate into a “useful vote” to keep the far-right away. At the same time, the right wing increased its fragmentation, with a dull Rui Rio leading the Social Democratic Party (PSD), and a growth of the far-right Chega, coming in third place with over 7%.

Having achieved its desired absolute majority, all the elements were in place for a period of stability led by the Socialist Party – which quickly crumbled down when the Prime Minister Costa and several members of his close circle saw themselves involved in investigations of illegalities and alleged corruption cases around lithium and green hydrogen. Although Costa was not accused of any crime, the suspicions of his potential involvement in the cases of influence peddling and corruption led to his resignation, and to the subsequent dissolution of the parliament in December 2023, calling for new elections.

The corruption cases turned out to be a blessing for the far-right Chega, who based its campaign on anti-corruption and anti-immigration stances, under the slogan “clean Portugal”. They have benefited from the anti-democratic right gaining momentum throughout Europe, having recently joined the Identity and Democracy (ID) group – alongside the German AfD, Salvini’s Lega and Le Pen’s Rassemblement National. Internally, they have equally bad influences, such as the MP Pacheco de Amorim, a former member of the far-right terrorist group MDLP and grandson of a monarchist close to Salazar. The party’s savior-like leader, André Ventura, previous member of PSD, used his ex-TV football commentator platform for his political project, becoming famous by attacking Roma communities, and later on bringing back a reminiscence of the dusty “god, country and family” fascist regime slogan.

Supported by a right-leaning mainstream media that is always running after their next clickbait, and using social media to reach young voters, Chega has wrongfully masqueraded as a home to those who feel forgotten and neglected – such as those living in Algarve, a very touristic district in the south of Portugal, where the party was the most voted. The region, which has seen a spike in tourism, has been severely affected by low wages, precarious and seasonal labor agreements, increases in the housing prices and struggles in the access to healthcare, illustrating the PS’s absolute majority government’s failure in tackling people’s problems, as pointed out by the left parties. In this sense, Chega rode the wave of labeling themselves as an “anti-system” protest party, when they are, in fact, a strong advocate for the capitalist system, as they receive funding from major economics groups and represent the worst of the political establishment.

What happens now?

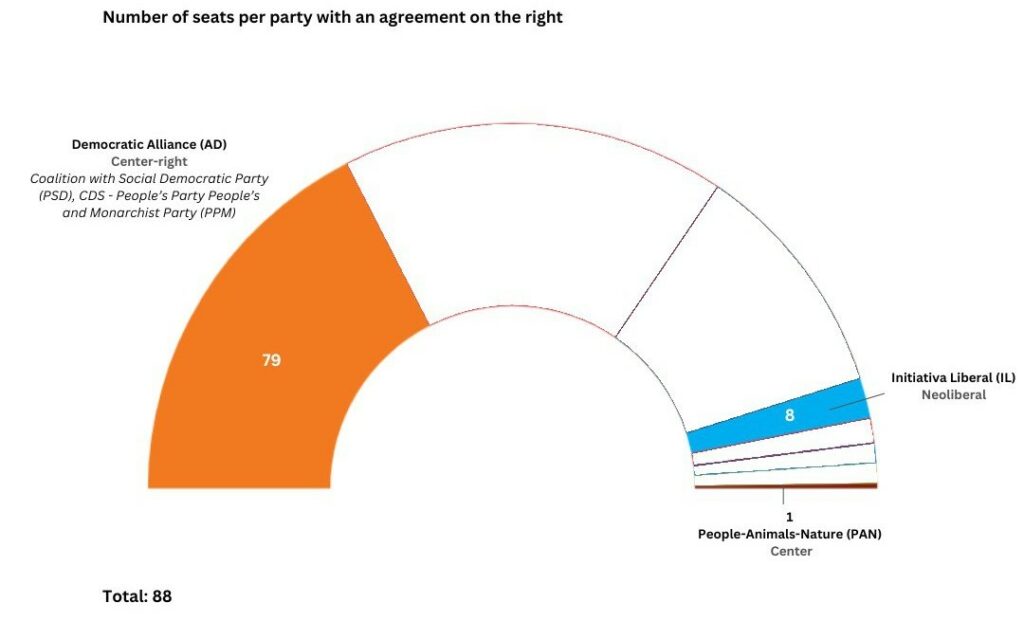

Despite the narrow win of the Democratic Alliance – a party that includes the conservative CDS, whose vice-president Paulo Núncio has defended a new referendum to revert abortion rights – the election results mark the country’s shift to the right. The Democratic Alliance’s victory was so marginal that they’re unable to form a governing majority with their preferred partner, the neoliberal Liberal Initiative (IL), that came in fourth place. This suggests that a right-wing majority set up without Chega will be out of the question.

With neither of the two mainstream parties able to secure a majority ruling coalition, the country is at a crossroads, which brings the question of governability to the center. A moderate alliance between the Socialist Party and the Democratic Alliance is out of the picture, as the new socialist leader Pedro Nuno Santos has already assumed the opposition role, and both parties led a campaign incompatible with that. A socialist rejection of the center-right budget bill will result in new elections, and AD’s leader, the social democrat Luis Montenegro, might go afterwards for a campaign requesting an absolute majority, under the disguise of stability.

Faced with this scenario, will Montenegro remain true to his “no is no” response to the racist Chega (who has already threatened to reject the state budget if there are no negotiations) by honoring his unwillingness to work with the far-right party? Or will he give into an agreement with the anti-democratic force to approve the 2025 state budget? Mariana Mortagua, leader of the Left Bloc, has her suspicions: “Are we completely at peace and confident that, when the time comes and they need to get power, the right won’t find a way to make an agreement between themselves?”.

A third hypothesis might thicken the plot, one that echoes the Social Democratic Party’s internal fragmentation, which might go as far as bringing back the austerity king, Pedro Passos Coelho. The former Prime Minister (between 2011 and 2015) and former PSD’s president, Passos Coelho goes down in history with a bad track record of carrying out salary and pension cuts, proudly implementing the EU-IMF austerity package and even suggesting that the solution to unemployment of the youth was to emigrate. He might be more willing to find agreements with the far-right than Montenegro. The leader of the People’s Monarchist Party (PPM), another right-wing coalition partner of AD, has also shown his openness to negotiate: “I don’t see any harm. I wasn’t at all scared of an opening to Chega”.

However, not all is lost. Although to the left of the Socialist Party, the communist PCP lost two seats, the pro-European left party, Livre, almost tripled their vote, securing four seats. The Left Bloc also resisted, keeping their 5 MPs and increasing their votes by around 30.000 against the 2022 election – forming a strong opposition bloc.

Hope is not obscene

Portugal’s politicians operate in one of western Europe’s poorest countries, where the minimum wage is set at 820€/month, with a skyrocketing housing crisis (that has set the average rental price in Lisbon at 2.000€/month), part of the populations finding solace in populist, inflamed speech out of desperation. In this sense, I’m reminded of Ken Loach’s most recent movie, The Old Oak, which asks: isn’t hope obscene?

Faced with a period of political turmoil, in which the far-right insists on refocusing the debate by pointing fingers and fabricating logics of us against them, the traditional right-wing bears responsibility, by so often being unable or unwilling to hold their ground, and legitimizing a discriminatory agenda. We cannot afford to give into the demagogic tactics of creating false enemies instigated by hate speech and racist ideologies. It is the democratic parties’ role, more than ever, to roll up their sleeves. For the left, that means we must continue to do what we do best, while also reflecting on new strategies to do so: to give voice and body to the concrete material struggles, which in the Portuguese case, means tackling the low wages, the housing crisis, and access to healthcare.

On the latter point, it is imperative to continue to relentlessly defend one of the April Revolution’s biggest conquests: the public National Health Service (SNS), which guarantees universal and free access to health care for all, and which has been systematically threatened with underinvestment and drained by the private sector, thus degrading its public facet.

At the same time, the country is faced with a severe housing crisis. This has been fueled by a 2008 financial crisis recovery plan based on foreign investment – supported by government measures (such as special tax schemes for digital nomads, or the Golden Visas) – and a spike in the tourists seeking short-term rentals, diverting homes to tourism instead of residential use. These factors have resulted in the prices rising so much that affordable housing for the country’s average income is no longer a reality (in a place with one of Europe’s lowest public housing percentage of around 2%). People are being pushed out of the major urban centers, such as Porto and Lisbon (where the housing prices have increased by 120% between 2012 and 2022). This is the case when they are not evicted from their homes altogether and facing homelessness. The social movements and the left parties have been organizing around this – namely through major national demonstrations that gathered thousands of people under the slogan “A House to Live” – and particularly in Lisbon through a local referendum inspired by the one done in Berlin by Deutsche Wohnen Enteignen. Yet, the parties in power have systematically failed to tackle the issue.

In the year that celebrates the 50th anniversary of the Carnation Revolution, its heritage is well remembered by the foundational stones it built that brought profound changes to Portuguese society, and which need to be defended today: labor rights, housing, universal healthcare and reproductive rights. Reclaiming a political agenda that offers real solutions with rights and justice at the center is the only way to counteract the feeling of abandonment and lack of hope, which Loach’s The Old Oak so beautifully replies to, by illustrating that shared spaces of encounter and understanding are desperately needed to bring back community and those who feel alienated and abandoned.

There’s much we can learn from those who fought at the time for bread, freedom, and roses – or, in this case, red carnations: flowers that year after year fill the streets on 25 April, alongside those shouting “Fascismo Nunca Mais” (“Fascism Never Again”). The rise of the far right might try to stain the memory of the revolution, but just like 50 years ago, we’ll be many on the streets. Our red carnations are not withering; we’re just on time to start planting them again.