The German domestic intelligence agency, known as the Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz [Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution] or simply as Verfassungsschutz, is comparable to such agencies as the FBI or MI5. One of its central remits is monitoring organisations considered potentially dangerous or anti-democratic, whether on account of ties to organised crime or ideological extremism. These include mosques and their congregations, far right gun clubs or anarchist groups.

One of the more high-profile cases involved the NPD (National Democratic Party of Germany), a neo-Nazi party. It has become largely irrelevant since the rise of the AfD (Alternative for Germany) but was for some years considered sufficiently dangerous to justify a ban. The protracted legal process was ultimately stymied because the investigations had been overly dependent on confidential informants. In some cases they were so influential as to compromise the integrity of the enterprise, as the intelligence agency was effectively running party activities. The parliamentary petition to prohibit the party was rejected by the constitutional court first in 2003 and then, after a renewed attempt in 2013, once more in 2017 – this time because the party was now considered too insignificant to constitute a real threat to democracy.

Numerous MPs belonging to Die Linke [The Left Party] were under intelligence observation between 2007 (the year of the party’s foundation) and 2013. Certain members had even been spied on since before then. Since 2019, the AfD as a whole has been granted this dubious honour at the lowest level (as a Prüffall, ‘case for assessment’), and parts of its Thuringian branch at the next-highest level (as a Verdachtsfall, ‘case for suspicion’).

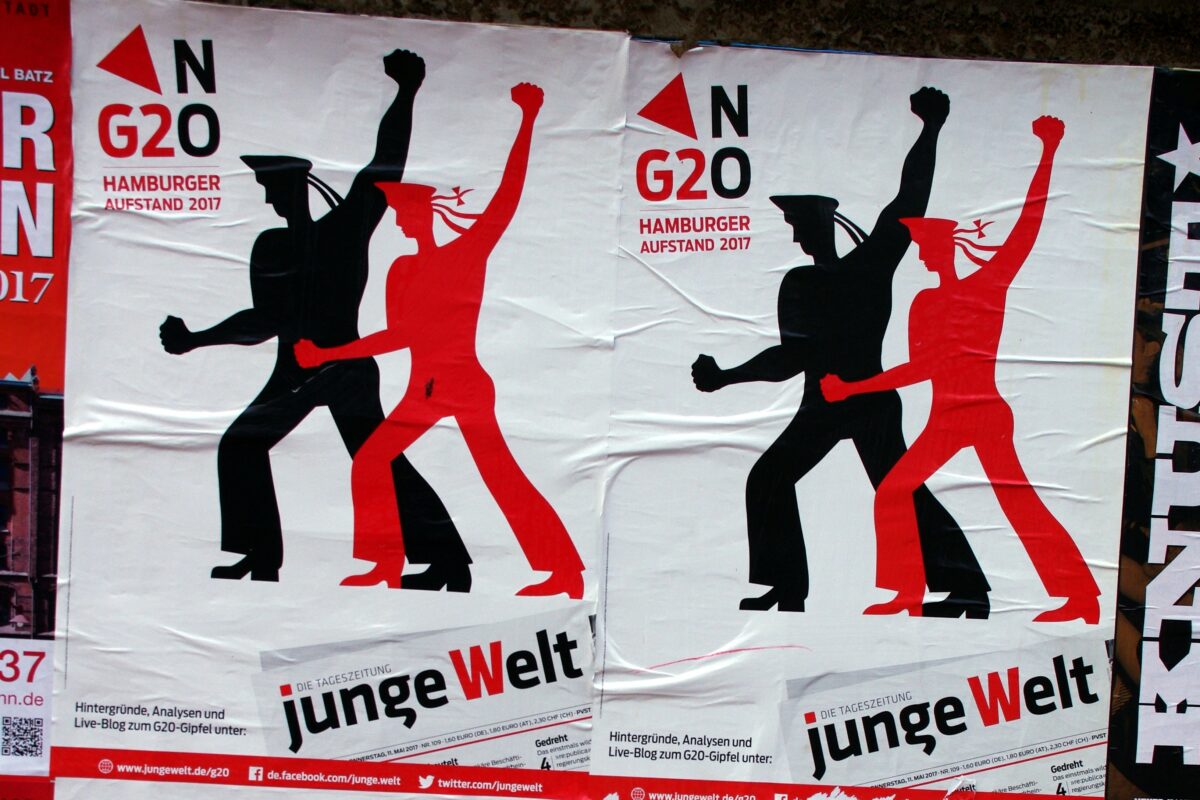

The daily newspaper junge Welt [Young World] has existed since 1947, and was the leading publication in the GDR as well as the official voice of the communist youth organisation FDJ (Free German Youth). Following German reunification, years of uncertainty passed in the hands of various publishing groups. It briefly folded, but re-launched in the early 90s with a new publishing house (Verlag 8. Mai) and cooperative ownership. It is now the largest leftist newspaper, with a clear anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist position that sets it apart from other significant left-wing publications such as the taz.

On 13 March this year, the editors and publisher of junge Welt addressed an open letter to the heads of all parliamentary parties. In it, they revealed not only the fact that the paper is under observation, but also the effects this has on its dissemination and survival:

- In several cities, the paper is not allowed to rent advertising space in public transportation.

- The German rail service (Deutsche Bahn) refuses to allow the paper to rent advertising spaces in stations.

- Several radio stations refuse to broadcast paid commercials.

- A major supermarket chain tried to prevent the paper from being sold in its branches.

- A printing shop refused to print a magazine whose publisher had already paid and provided a ready-to-print file because it contained an advertisement for junge Welt.

- At the University of Frankfurt, it is forbidden for junge Welt to advertise that it can be bought at kiosks.

- Numerous libraries block access to the junge Welt website.

- In some prisons, junge Welt is listed as a forbidden publication and not delivered to subscribers.

- Teachers dealing with the subject of daily newspapers who mention junge Welt have encountered problems that have caused them to take legal action.

In every single one of these cases, the reason given for these restrictions is the same: the newspaper is under intelligence observation and/or appears in the annual intelligence report.

So what are the grounds on which the Verfassungsschutz maintains this observation of Junge Welt?

After the newspaper sent its open letter to senior MPs, the parliamentary group of Die Linke sent an enquiry to the government asking this question. As well as naming the restrictions faced by the newspaper listed above, they also referred to a judgement by the supreme court in a dispute between the far-right weekly Junge Freiheit [Young Freedom] and the state of North Rhine-Westphalia in 2005. The court had ruled that publishing the paper’s name in the intelligence report would be a violation of the constitutional right to freedom of press, a violation of the right to communication and an unacceptable restriction of its possibilities for dissemination and economic survival. The ruling emphasised that it was undemocratic to allow only publications representing a certain area of political opinion. It also pointed out that even if individual authors express potentially anti-democratic views, the publication itself could not necessarily be held accountable for these, and any such cases would require specific examination.

In a democracy that promotes freedom of press, one should be able to take these principles for granted. Whatever the political orientation of a publication, anything short of outright criminal incitement or conspiracy must be permitted, whether the authorities approve of these views or not.

On 5 May, two days after World Press Freedom Day, the parliamentarians received a response from the government. Because of junge Welt’s ‘extremist’ efforts to oppose the ‘liberal-democratic order’, the letter stated, it was important for the public to be informed of its activities. The paper’s classification as an extremist publication was based on the following arguments:

- junge Welt is a daily paper with a clear communist orientation. Its Marxist convictions have the implicit goal of replacing liberal democracy with a socialist/communist societal order.

- One of its revolutionary Marxist principles, the division of society according to production-based class membership, goes against the guarantee of human dignity; individuals must not be reduced to a ‘mere object’ or subordinated to a collective. The unconditional assignment of a person to a collective, an ideology or a religion, however, shows a disregard for the freedom of the individual.

- The paper’s Marxist orientation is further demonstrated by its reliance on the ideologies of Marxists-Leninist classics, especially by Lenin, Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht, Marx and Engels. This is underlined by the choice of topics and intensity of treatment, which does not reflect a broad spectrum of political opinions; instead, junge Welt disseminates its own subjective truth and seeks to create an antithesis to the wider public sphere [Gegenöffentlichkeit].

- With a daily circulation of 23,400 copies (27,000 on Saturdays), junge Welt reaches a substantial readership and can therefore disseminate its extremist, anti-constitutional views widely. These are augmented by the amplification of members of ‘extremist’ left-wing organisations at home and abroad, who are given the opportunity to air their revolutionary ideology. This characterisation is broadly applied to numerous national liberation movements. Because junge Welt does not distance itself from such views, they can be assumed to represent its own positions.

There are a number of variations on these themes on events and parties with which junge Welt is associated, as well as its purported sympathies with regimes classified as undemocratic. But the gist is clear from this list: the newspaper, which is not a political organisation but a journalistic product, has been stigmatised by state authorities for its Marxist, internationalist and anti-imperialist orientation. The report emphasises the dangers of its potential influence and asserts the need to undermine its material success. Ironically enough, the government justifies violating the laws of the free market and free competition by restricting the paper’s accessibility and visibility. What sort of capitalists are they?

Perhaps it is surprising that a state in which the principles of social democracy supposedly play an important part should permit such a suppression of leftist discourse while giving more leeway to far-right ideology. The unsavoury truth, however, is that Germany’s de-nazification was only superficial, and leftovers from those days have combined with neo-liberalism to produce a harmful cocktail. What better illustration of this could there be than the infiltration of state structures by far-right elements?

Perhaps the most visible example of this is the case of Hans-Georg Maassen, who was president of the Verfassungsschutz from 2012 to 2018. Public hostility towards him became most pronounced after he downplayed the racist violence at riots in the eastern city of Chemnitz in 2018, but he had argued for more restrictive immigration policy in his doctoral thesis as early as 2000. Around the same time as the riots, it also became known that Maassen had regular meetings with the AfD to give the leadership advice on avoiding intelligence observation. He is alleged to have shared information with them from the agency’s 2017 report before it was published.

By the summer of 2018, there was sufficient outrage at the sum total of Maassen’s exploits. He also made efforts to prevent access to files concerning the escaped senior Nazi Alois Brunner that same year. Finally the Interior Minister, Horst Seehofer, was forced to retire Maassen. In his farewell speech, Maassen painted himself as the victim of a leftist conspiracy to unseat him using fake news. In recent social media activities, he has propagated coronavirus denial and disseminated information from far-right sources.

Doubts about the integrity of the Verfassungsschutz predate Maassen’s tenure. The string of racist murders carried out by the terrorist group National Socialist Underground (NSU) between 2000 and 2007 (referred to in the tabloid press demeaningly as the ‘kebab murders’ for the Turkish background of many victims) became more widely known after the group was uncovered in 2011, and two of three principal members were found dead. It became clear that investigations had been impaired by a mixture of incompetence, complicity and concealment. Much is still unknown, but the revelations don’t show the police or the intelligence agency in a favourable light.

After Maassen’s departure, between 2018 and 2021, death threats and hate mail signed ‘NSU 2.0’ were sent to various individuals in politics, culture, the media and the justice system. Most were directed at women, who had either spoken out against far-right extremism in general or represented plaintiffs in the NSU proceedings. A lone culprit was found in early May. With indications that personal information on the recipients had been acquired through the police; as well as the existence of associated police chat groups with explicit neo-Nazi content; it is extremely unlikely that he acted on his own.

It is no secret that the police are more frequently hostile towards leftist protesters than those on the far right. As recent coronavirus protests have shown, they often show sympathies with far-right demonstrators. It is also no secret that the security establishment in general, from the police and intelligence agencies to the Interior Ministry, have often been at best inattentive to the dangers of far-right violence and at worst complicit. What is less known, however, is that the only leftist daily newspaper in Germany with a wide circulation is being observed, obstructed and prevented from doing its work by those who claim to protect constitutional democracy. This violation of freedom of press should be a source of national and international outrage.