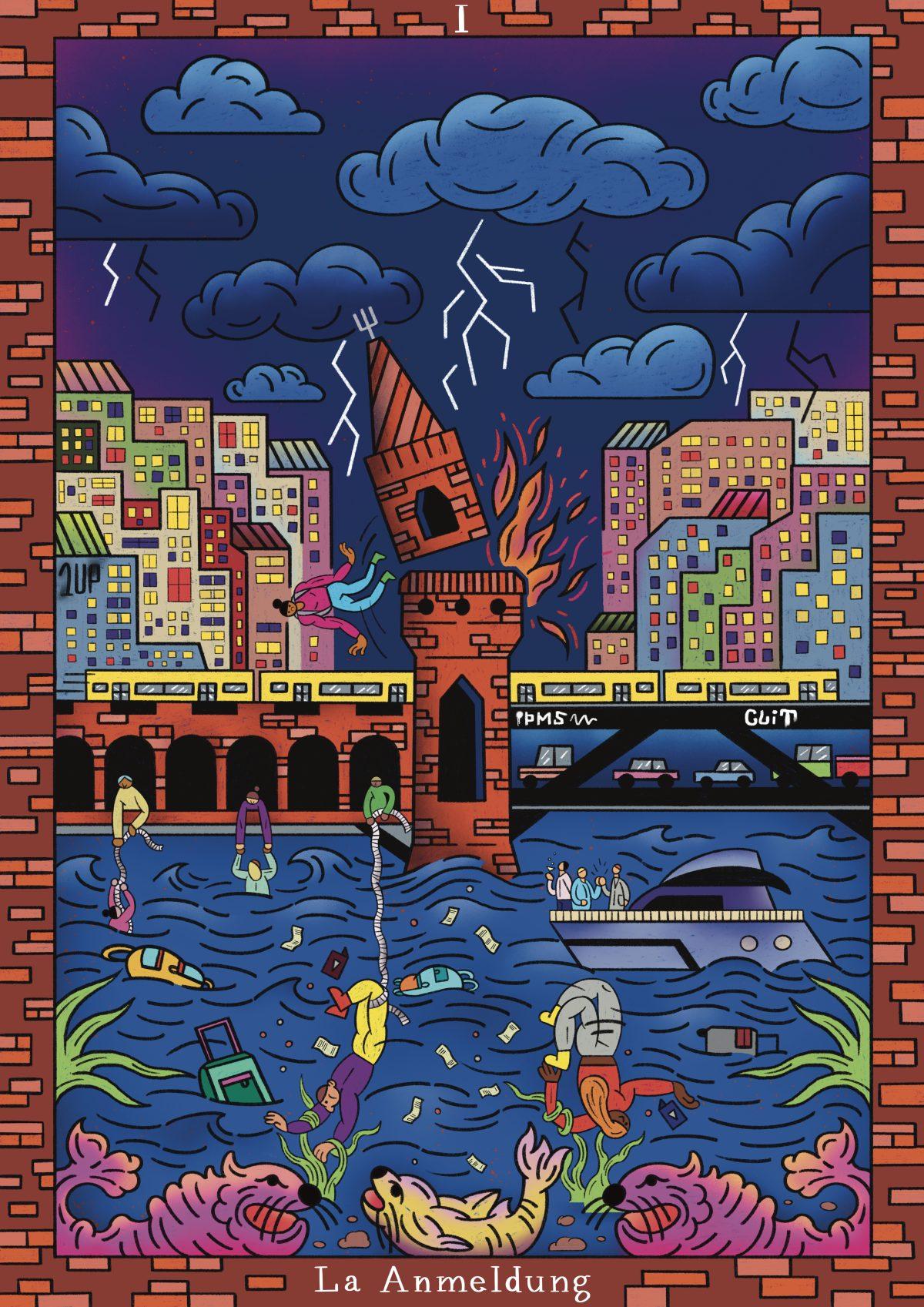

Migrants and royalty don’t usually have much in common, but Berlin is a special place. In Greek mythology, the gods condemned the monarch Sisyphus to push a massive boulder up a steep hillside. Just before reaching the top, however, the great stone rolled back down, and the accused had to start again from the beginning, over and over again for eternity. In the same absurd and frustrating way, most migrants who arrive in Berlin and cannot register their address [Anmeldung] are destined to face one rejection after another. Whether to open a bank account, get health insurance, sign an employment contract, obtain a tax ID or have an official address to receive mail – in Germany, an Anmeldung is required for almost every paperwork.

This bureaucratic obstacle is intensified by the most urgent social problem now: 700.000 housing units are needed in Germany [1]. Especially in Berlin, the increase in rents and the minimal supply of apartments in the city centre increasingly drive the inhabitants to the city’s outskirts. This isolates them from the main places of work, culture, health and sociability. Housing has ceased to be a social right aimed at satisfying a fundamental human need – to inhabit. It has become a commodity, something produced and sold on the market in order to generate profits.

The commodification of housing is the result of a relatively new historical form of capital accumulation, marked by the hegemony of finance and rent extraction over productive capital. This process of global financialization of the real estate market affects, of course, all people living under capitalism. It is tied to the transition from an industrial economy to a service economy, as financial services belong to the tertiary sector of the economy.

But the violence of it, combined with the bureaucratic functioning of German institutions, affects migrants in Berlin particularly severely. Fragile work visas, poor language skills and low-paid jobs in the cleaning, delivery and care sectors, make migrants the main victims of discrimination when applying for an apartment. They lack contacts and support networks to cope with this situation. Their only alternative is to pay exorbitant prices for tiny rooms that they can usually only sublet or rent temporarily. Under such precarious living conditions, it is practically impossible to register their address in public offices. This obstacle becomes a vicious circle of precariousness that consumes migrant life in Berlin. Without Anmeldung, new citizens remain excluded from the most essential urban goods and services and, above all, from the possibility of access to formal employment.

Berlin’s struggles for the Right to the City and the new role of Migrants

Berlin has a long tradition of urban protest. At various times since the 1970s, broad sectors of the population have organized to stop the demolition of old houses in working-class neighbourhoods [Altbauviertel]; to stop the construction of highways and large infrastructure projects; and to preserve the public character of spaces such as the Gleisdreick, Görlitzer Park and, the Tempelhofer Feld. One of the main protagonists in these struggles was the autonomist left sector. Together with students, unemployed and marginalized people, that organized a squatters’ movement [Hausbesetzerbewegung]. That came to control, during the 1980s, more than 200 houses in the Kreuzberg district and, after the fall of the wall, 130 in Friedrichshain. Women and non-conforming persons wrote an important but often forgotten chapter in this history of urban struggle. These sectors tried out various anti-patriarchal housing experiments based on cooperation, which took the form of legendary experiences such as Hexenhaus, Bülowstraße 55 and Tuntenhaus Forellenhof.

During the 1990s, the vast majority of Berlin’s self-managed housing projects were being legalized by the political power or evicted by the police. At the same time city government initiated an extensive and systematic sell-off of buildable lots and social housing to private investors. Between 1990 and 2017, a total of 21 million square meters of public land was sold, an area equal to the Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg district. Of 590,000 social housing units available at the beginning of that period, only about 270,000 remained in 2010. Crucially most of these 320,000 homes were not transferred to individual owners but to large real estate consortiums such as Deutsche Wohnen, Akelius & Co. and Vonovia. These consortia had one objective – the constant increase in the value of their shares, which deepened the processes of housing commodification and urban segregation.

As a result of social and political pressure exerted by the public and organizations representing the interests of tenants, the Berlin Senate enacted a law on February 24, 2020, setting a limit on the price of rent for certain types of housing [Mietendeckel]. The great concerns that this raised within the real estate lobby and the liberal party (FDP), the Christian Democrats (CDU) and the extreme right (AfD) were decisive for the legislation to be declared null and void by the German supreme court [Bundesverfassungsgericht] after approximately one year of being in force. However, in the context of the generalized crisis unleashed by Covid-19, the social discontent caused by the retroactive payment of the differences that had been received by the tenants benefiting from the Mietendeckel generated a favourable climate for the triumph of the campaign Deutsche Wohnen & Co. Enteignen. Organized by various individual and collective participants, this initiative succeeded in passing on September 26, 2021, a referendum proposing the expropriation of 243.000 housing units in Berlin that are in the hands of the three large consortiums mentioned above. The bill consists of creating a public law institution [Anstalt des öffentlichen Rechts] to administer the properties and carry out a progressive compensation to the shareholders for an amount significantly lower than the market value of the properties. However, the real estate lobby and the aforementioned parliamentary alliance, in which the Social Democracy (SPD) is also an accomplice, have succeeded in blocking its implementation over the past two years.

A novel historical feature of the struggles for the right to the city was the political participation of migrants. The conflicts over the occupations in Kreuzberg during the 1980s were led by German leftist groups. But the protests of the new century highlight, instead, the role that racialized families in neighbourhood initiatives such as Kotti & Co or the encampment at Oranienplatz and the occupation of the Gerhard-Hauptmann school building. These were carried out by migrants and illegalized people between 2012 and 2014. These experiences are meaningful because they confer visibility, for the first time, to different groups that had previously been marginalized from urban debates. It gave them the possibility to demand answers to the problems that afflict them: “Who has the right to live in the “centre” of the city? Those with more economic resources, those who have lived here for generations, or those who identify with a particular urban lifestyle? On what criteria are these habits and lifestyles defined? Is it possible to defend them against commodification? What does the exclusion from the right to vote mean and, how does that affect democracy in the city?”

Translating the Language of Struggle on the Social Production of Habitat

Ciudad Migrante is a space organized by the “Bloque Latinoamericano“, in which anyone can participate to reflect on the real estate market and bureaucracy effects on migrant life in Berlin. Its main objective is self-organization and mutual aid, to develop collective solutions to the housing access problem. Over the past year, the participants of the initiative have developed communication tools to help migrants to better understand their rights as tenants and, above all, to defend them. In collaboration with artists and geographers, illustrations, videos, texts and maps were produced to provide critical guidance on navigating the process of finding an apartment in Berlin. In a practical and accessible way, these resources explain key mechanisms. These include how a room can be obtained; the characteristics, rights and obligations of the different types of rental contracts; the common scams to watch out for; directions to resources to counter gender-based violence in the home; and many other indispensable informations that are required when arriving in an unfamiliar city.

But beyond their analytical and communicative function, Ciudad Migrante’s tools are conceived as instruments for training and political action to fight against the precariousness generated by bureaucracy and the real estate market. These resources express the concrete needs of the Latino population in Berlin. Their political inspirations are borrowed from Consejos Comunales de Venezuela, Federación Uruguaya de Cooperativas por la Ayuda Mutua (FUCVAM), Movimiento de Ocupantes e Inquilinos (MOI) of Argentina and Movimiento de Trabajadores sin Techo (MTST) of Brazil. Those are just a few of the best-known experiences of urban struggle in the South America. Despite the vast diversity of political traditions, all these organizations resulted from the engagement of the people in the processes of social production of habitat. It is the common language of self-organization that the Bloque Latinoamericano chooses to articulate, with its own voice, before the State and the parliamentary parties in Berlin, terms and conditions of the migrant struggle for the right to the city.

Footnote

[1] This is the main conclusion of the study “Building and Living in the Crisis – Current Developments and Implications for Construction and Housing Markets“, presented on 12.01.2023. The analysis was commissioned by the Berlin “social housing” initiative [Soziales Wohnen], in which the IG BAU trade union, the tenants’ association [Mieterbund], a Caritas social unit and two builder’s associations are involved.

This article originally appeared in Spanish on the Bloque Latinoamericano website. Reproduced with permisson.